Crook Manifesto Summary, Characters and Themes

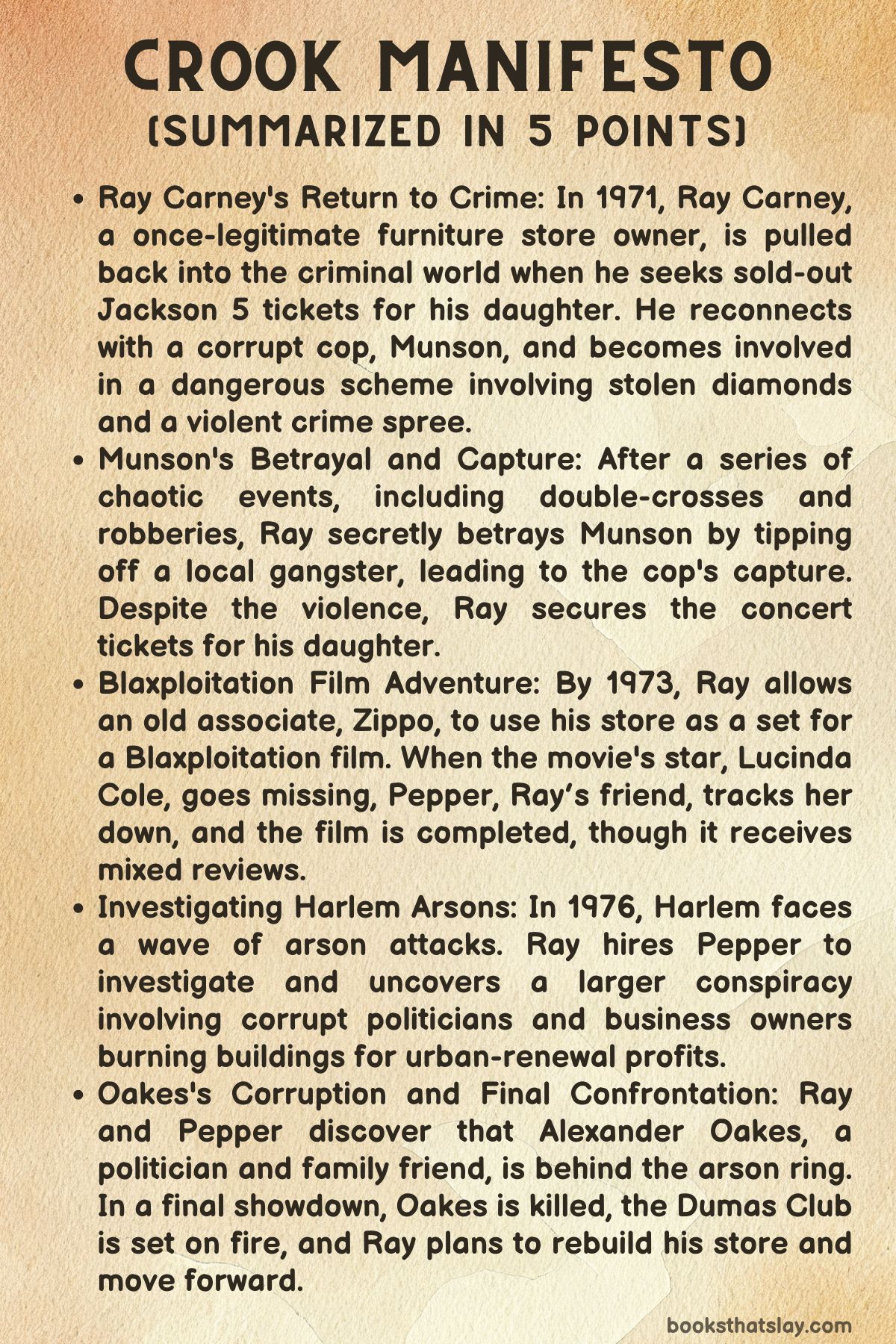

Crook Manifesto is the gripping second installment in Colson Whitehead’s Harlem-based crime trilogy, following 2021’s Harlem Shuffle. Set in the turbulent 1970s, the novel revolves around Ray Carney, a furniture store owner navigating a fine line between his respectable life and the pull of his past in the criminal underworld.

Through Ray’s interactions with crooked cops, filmmakers, and arsonists, Whitehead deftly weaves a tale of corruption, crime, and community amidst the changing landscape of Harlem. With its blend of crime, social commentary, and dark humor, Crook Manifesto brings 1970s New York City to life.

Summary

In 1971, Ray Carney, now the respectable owner of a successful furniture store, has left behind his days of dealing in stolen goods. Life has been good—he’s a family man, focused on his wife, Elizabeth, and their children, May and John. But when May begs for tickets to a sold-out Jackson 5 concert, Ray finds himself turning back to his old contacts.

He reaches out to Munson, a corrupt police officer, who agrees to help—but there’s a catch. In exchange for the tickets, Ray must find a buyer for a stash of stolen diamonds. These diamonds, however, turn out to be hot property, linked to a major heist that makes them nearly impossible to move.

Things quickly spiral out of control. Ray is double-crossed by Munson’s shady partner, Buck, who beats him up and steals the diamonds. After regaining consciousness, Ray teams up with Munson to track Buck down. Munson kills Buck in cold blood and tells Ray they’re now partners in crime.

The duo embark on a violent spree, robbing poker games, bars, and more before Ray finally sees a way out. He secretly tips off a local gangster about Munson’s whereabouts, leading to Munson’s capture. Against all odds, Ray gets the Jackson 5 tickets after all and takes May to the concert, ending the first section.

By 1973, Ray has quietly slipped back into his old ways, once again running stolen goods on the side. He reconnects with Zippo, a filmmaker with dreams of shooting a Blaxploitation movie in Harlem. Zippo convinces Ray to let him use his furniture store as a film set, bringing Ray into the orbit of a colorful cast of characters, including Pepper, an old associate hired for security.

When the film’s star, Lucinda Cole, goes missing, Zippo sends Pepper on a mission to track her down. After a winding chase through various parts of Harlem, from shady comedy clubs to drug dens, Pepper finds Lucinda and brings her back.

The film is eventually completed, though its reception is mixed. Still, Zippo is thrilled, heading to France to promote it.

The final section, set in 1976, takes a darker turn. As Harlem grapples with a wave of arsons, Ray begins to suspect a sinister plot.

He hires Pepper to investigate, and the two uncover a scheme involving corrupt politicians, contractors, and landlords setting buildings ablaze to cash in on urban renewal funds. When Ray’s own store is firebombed, the conspiracy becomes personal.

Their investigation leads to a shocking discovery: Alexander Oakes, a prominent local politician and childhood friend of Elizabeth, is at the heart of the arson racket. In a violent confrontation at the Dumas Club, Oakes is killed, and the club is set ablaze.

Ray and Pepper barely escape with their lives, leaving Ray to plan the rebuilding of his business and his future.

Characters

Ray Carney

Ray Carney is the protagonist of Crook Manifesto, a complex character caught between the worlds of legality and criminality. At the start of the novel, Ray is a successful furniture store owner in Harlem, having distanced himself from his past life as a fence for stolen goods.

His primary focus is on his family—his wife, Elizabeth, and their two children, May and John—and his legal business, which symbolizes his attempts at upward mobility in a society where opportunities for African Americans are limited. Ray’s struggles reflect his desire to escape Harlem’s crime-infested environment, but he is repeatedly pulled back into the underworld.

His decision to contact a crooked cop, Munson, to secure Jackson 5 concert tickets for his daughter shows his lingering vulnerability to corruption and old habits. Throughout the novel, Ray’s character is defined by his moral ambiguity.

Despite his efforts to be a law-abiding citizen, Ray finds himself engaging in increasingly dangerous criminal activities, from fencing stolen goods to assisting Munson in violent robberies. His deepening involvement in the criminal underworld in later parts of the novel, particularly his partnership with Pepper, shows that he is unable to escape the shadow of his father’s criminality.

As the novel progresses, Ray evolves from a reluctant participant in crime to a man who must actively confront the corrupt systems around him. This is especially seen in his pursuit of justice against the organized arson scheme plaguing Harlem.

In the end, Ray’s decision to rebuild and expand his store is symbolic of both his resilience and his entrenchment in the complex, morally grey realities of Harlem.

Pepper

Pepper is an older, enigmatic character whose life as a hired hand in criminal circles contrasts sharply with Ray’s attempts to lead a more legitimate life. A former associate of Ray’s father, Mike, Pepper represents a figure of continuity between the generations of Harlem’s underworld.

He is a seasoned and stoic man who operates as both a protector and enforcer. In the second part of the novel, Pepper is hired by Zippo to run security on a film set, showcasing his reliability and skills in deterring criminal interference.

However, Pepper’s role expands as he becomes involved in the search for Lucinda Cole, revealing his investigative skills and tenacity. He uses his street smarts and connections to track down Lucinda, showcasing his capacity to navigate the dangerous terrain of Harlem’s criminal elements.

In the third part of the novel, Pepper’s investigation into the rising number of arsons in Harlem highlights his deeper, more philosophical side. He becomes Ray’s ally in uncovering the corruption behind the fires, which ultimately leads to the novel’s climactic confrontation.

Pepper’s stoicism and experience serve as a counterpoint to Ray’s more conflicted morality. By the end, Pepper’s role in taking down the corrupt Alexander Oakes solidifies his position as both a protector and a survivor in Harlem’s unforgiving landscape.

Munson

Munson, a corrupt New York City police officer, embodies the lawlessness and moral decay of the 1970s New York City police force. His relationship with Ray is complex and manipulative.

While Ray reaches out to him for help in obtaining Jackson 5 tickets, Munson leverages this opportunity to pull Ray back into criminal activity. Munson’s actions reveal him as an opportunist who has no qualms about violence or betrayal.

His murder of his partner, Buck, and his subsequent crime spree with Ray highlight his recklessness and complete disregard for the law. Munson’s escape from the law by fleeing from a police corruption investigation further underscores his self-serving nature.

He is a man who thrives on exploiting the system’s weaknesses. His eventual capture after Ray tips off a local gangster marks his downfall.

Zippo

Zippo, a former criminal associate of Ray and Freddie’s, represents a different path than that of Ray and Pepper. Having turned his back on the life of crime, Zippo has become a successful filmmaker and artist.

His journey from a life of illegality to earning an art degree and making Blaxploitation films mirrors the possibilities of reinvention and upward mobility within Harlem. However, despite his artistic success, Zippo’s ties to his past remain evident in his relationships with Ray and other criminals.

Zippo’s passion for filmmaking drives him to involve Ray’s furniture store in his production, and his enthusiasm for his art sometimes borders on naivety. This is especially clear when contrasted with the darker realities Ray and Pepper face.

His character adds a layer of cultural commentary to the novel, as he attempts to create art that reflects Harlem’s vibrancy and complexity. Zippo’s success in promoting his film in France shows his ability to transcend Harlem’s limitations, yet his ties to the neighborhood and its criminal underworld remain strong.

Elizabeth Carney

Elizabeth, Ray’s wife, represents stability and morality in Ray’s life, though her presence in the novel is somewhat understated compared to the more dynamic, crime-driven plotlines. She is aware of Ray’s past and his struggles to stay on the right path.

Elizabeth is largely a grounding force, committed to raising their children and maintaining their family life. Her childhood connection to Alexander Oakes adds an interesting dimension to her character, as her moral integrity contrasts with Oakes’s descent into corruption.

While she is not directly involved in the criminal activities that consume Ray’s life, her expectations and the life they have built together serve as a backdrop to Ray’s internal conflict. Elizabeth’s role in the novel highlights the tension between family life and the criminal world that Ray continually straddles.

Alexander Oakes

Alexander Oakes is a corrupt politician and childhood friend of Elizabeth who rises to prominence in Harlem’s political landscape. His character represents the pervasive corruption within the city’s political and economic structures.

Oakes initially appears as a charismatic figure with political ambitions, but as Ray and Pepper investigate the arson plaguing Harlem, Oakes is revealed to be deeply involved in an organized crime network that benefits from the destruction of Harlem’s buildings.

His participation in the arson scheme, which preys on the vulnerabilities of Harlem’s residents, makes him one of the novel’s primary antagonists. Oakes’s descent into crime and his eventual death during the climactic shootout reveal the extent to which power and greed can corrupt individuals who once seemed to hold promise for the community.

His character serves as a critique of the political and economic forces that exploit urban neighborhoods for financial gain.

Lucinda Cole

Lucinda Cole, a central figure in the second part of the novel, is a rising actress in Zippo’s Blaxploitation film who suddenly goes missing. Her disappearance prompts Pepper’s search, which unravels a web of relationships, debts, and personal turmoil.

Lucinda’s character represents the tensions between personal identity and public persona, as her real name and background are concealed beneath the glamorous image she presents in the entertainment industry.

Her character also adds a layer of complexity to the film world depicted in the novel, where art and reality intersect with crime and exploitation. Lucinda’s eventual return to Harlem with Pepper speaks to her own struggles with identity and belonging.

Buck

Buck is Munson’s crooked partner and serves as an antagonist in the first part of the novel. His decision to mug Ray and steal the diamonds Munson had acquired through a heist showcases his greed and disloyalty.

However, Buck’s character is short-lived, as he is murdered by Munson, reflecting the brutal and treacherous nature of the criminal world Ray becomes entangled in. His actions set off a chain of events that further embroil Ray in Munson’s violent schemes.

Buck serves as a reminder of the dangers lurking in Ray’s past life, reinforcing the novel’s themes of betrayal and survival in a corrupt environment.

Themes

The Complex Intersection of Legitimacy and Illegitimacy in Urban Spaces

One of the most intricate and pervasive themes in Crook Manifesto is the blurred line between legitimate and illegitimate activities in Harlem, particularly as they relate to survival and ambition in a structurally unequal society. Ray Carney’s dual life as both a respectable business owner and a former (and reluctant) criminal highlights the difficulty of remaining completely law-abiding in a space that itself is marked by corruption and inequality.

Whitehead complicates traditional ideas of morality by suggesting that survival in Harlem’s hostile urban landscape often requires pragmatic decisions that blend legality and illegality. Ray’s turn to a crooked cop, Munson, to acquire Jackson 5 tickets for his daughter underscores how even seemingly innocuous desires—like being a good father—can force individuals into corrupt exchanges.

Furthermore, the novel’s depictions of property crime and arson in the final part show how broader economic and political systems also blend legality with exploitation. Here, Whitehead points to the role of city officials and property developers in orchestrating arson for profit, implicating the entire urban structure in this web of criminality.

Thus, the novel poses a critical question: what is truly legitimate in a space where even city planning is driven by criminal motives?

The Corrosive Impact of Systemic Corruption on Identity and Morality

Crook Manifesto explores how pervasive corruption affects personal identity and moral choices, particularly for African American characters navigating life in 1970s Harlem. Ray Carney’s journey demonstrates how systemic corruption doesn’t simply exist outside the individual but also penetrates the internal moral calculus of people who try to lead respectable lives.

His moral compass is constantly challenged by external pressures to return to the criminal world, especially as Harlem’s environment offers few avenues for upward mobility without entanglement in some form of corruption. The character of Munson, a crooked cop who blurs the lines between law enforcement and crime, symbolizes the breakdown of institutional morality, making it nearly impossible for individuals like Ray to navigate Harlem’s moral landscape without compromising themselves.

Pepper’s character reflects the internal toll of living in a corrupt society. His violence, though often pragmatic, reveals how deeply ingrained the logic of survival has become in an environment where systemic injustice erodes any clear sense of right and wrong.

Through these characters, Whitehead portrays corruption not just as an external force but as a condition that shapes the identities, moral reasoning, and survival strategies of people embedded in corrupt systems.

Urban Decay, Arson, and the Commodification of Destruction

A significant and layered theme in Crook Manifesto is the commodification of urban decay, specifically how the destruction of Harlem through organized arson becomes a tool for profit within a framework of systemic exploitation. In Part 3, the rising number of arsons is not depicted as mere acts of isolated criminality but rather as part of a broader economic strategy that benefits corrupt city officials, developers, and others who stand to gain from the aftermath.

This commodification of destruction ties directly into the processes of urban renewal, as the burned buildings open up space for new developments that serve the financial interests of the elite rather than the local residents. The theme here is not just about the destruction of physical buildings but the erasure of communities and livelihoods, pointing to the darker underbelly of capitalism where destruction itself becomes a valuable commodity.

By showing how Harlem’s own political figures, like Alexander Oakes, are directly involved in this system, Whitehead highlights the complicity of local power structures in the exploitation and devaluation of African American urban spaces. The novel positions arson as a symbol of broader urban blight, where entire neighborhoods are sacrificed for profit under the guise of renewal, reflecting historical realities of redlining and gentrification in American cities during this period.

Cultural Representation, Black Art, and the Commercialization of Identity

Through the subplot of Zippo’s Blaxploitation film in Part 2, Whitehead addresses another intricate theme: the commercialization and commodification of Black identity and culture. Zippo’s transition from small-time criminal to filmmaker reflects a broader moment in American culture during the 1970s when Black artistic expression became commercialized, particularly through film and music.

Blaxploitation films, although created by Black filmmakers and often addressing themes relevant to African American life, were also consumed and profited upon by white audiences and mainstream studios, leading to a tension between cultural representation and economic exploitation. In Crook Manifesto, Zippo’s excitement about his film, and its moderate success, reflects both the possibilities and the limitations of such commercial ventures.

On one hand, the film allows for creative expression and representation of Black life in Harlem, but on the other, it is part of a larger industry that profits from the commodification of Black culture. This theme is further complicated by the character of Lucinda, whose disappearance and return symbolize the tension between personal identity and public persona in the context of a film industry that often reduces complex lives to stereotypical roles.

Whitehead’s exploration of this theme points to the difficult balancing act between authenticity and commodification in Black cultural production during the 1970s.

The Familial Struggle for Stability in a Context of Urban Instability

A more nuanced and layered theme in Crook Manifesto is the idea of family as a stabilizing force in an otherwise unstable urban environment. Ray’s relationship with his wife Elizabeth and his children, particularly his desire to provide for them, forms a central motivation for his actions throughout the novel.

However, the family’s pursuit of stability is constantly under threat from the larger forces of crime, corruption, and urban decay that dominate Harlem. For Ray, family is both a reason to pursue legal avenues and the motivation that sometimes drives him back into illegal enterprises.

The tickets to the Jackson 5 concert, for example, are not simply a material object; they represent Ray’s deep desire to provide joy and normalcy for his daughter May, even if it means crossing moral and legal boundaries. This tension between providing for his family and navigating Harlem’s perilous environment mirrors the larger African American experience of trying to maintain familial integrity in a society structured to destabilize Black lives through systemic racism, economic disenfranchisement, and urban neglect.

Elizabeth’s role, too, highlights the struggles of balancing aspirations for a better life with the harsh realities of living in Harlem. Family, in this context, becomes both a source of hope and a site of conflict, caught between the aspirations for upward mobility and the structural limitations of their environment.

Power, Politics, and the Illusion of Social Progress

Crook Manifesto interrogates the nature of power, politics, and the illusion of progress, particularly through its depiction of Alexander Oakes, the politician running for borough president in Part 3. Oakes represents the hollow promises of political figures who claim to serve the community but are, in fact, deeply complicit in its exploitation.

His involvement in the arson scheme underlines the hypocrisy of political rhetoric about progress and improvement, showing how these figures often profit from the very systems of oppression they claim to be dismantling. This theme extends beyond individual corruption, however, to critique the larger political and social systems that allow such figures to thrive.

Whitehead uses Oakes as a vehicle to explore how Black communities, despite the civil rights advancements of the 1960s, continue to face systemic violence and exploitation under the guise of urban development and political progress. Ray’s disillusionment with Oakes and the political process in general reflects a broader skepticism toward institutional power and its ability to deliver real change.

This theme suggests that the supposed social progress of the 1970s, particularly in Black urban spaces, is often an illusion, masking the deepening exploitation and marginalization of African American communities.