Evil Eye by Etaf Rum Summary, Characters and Themes

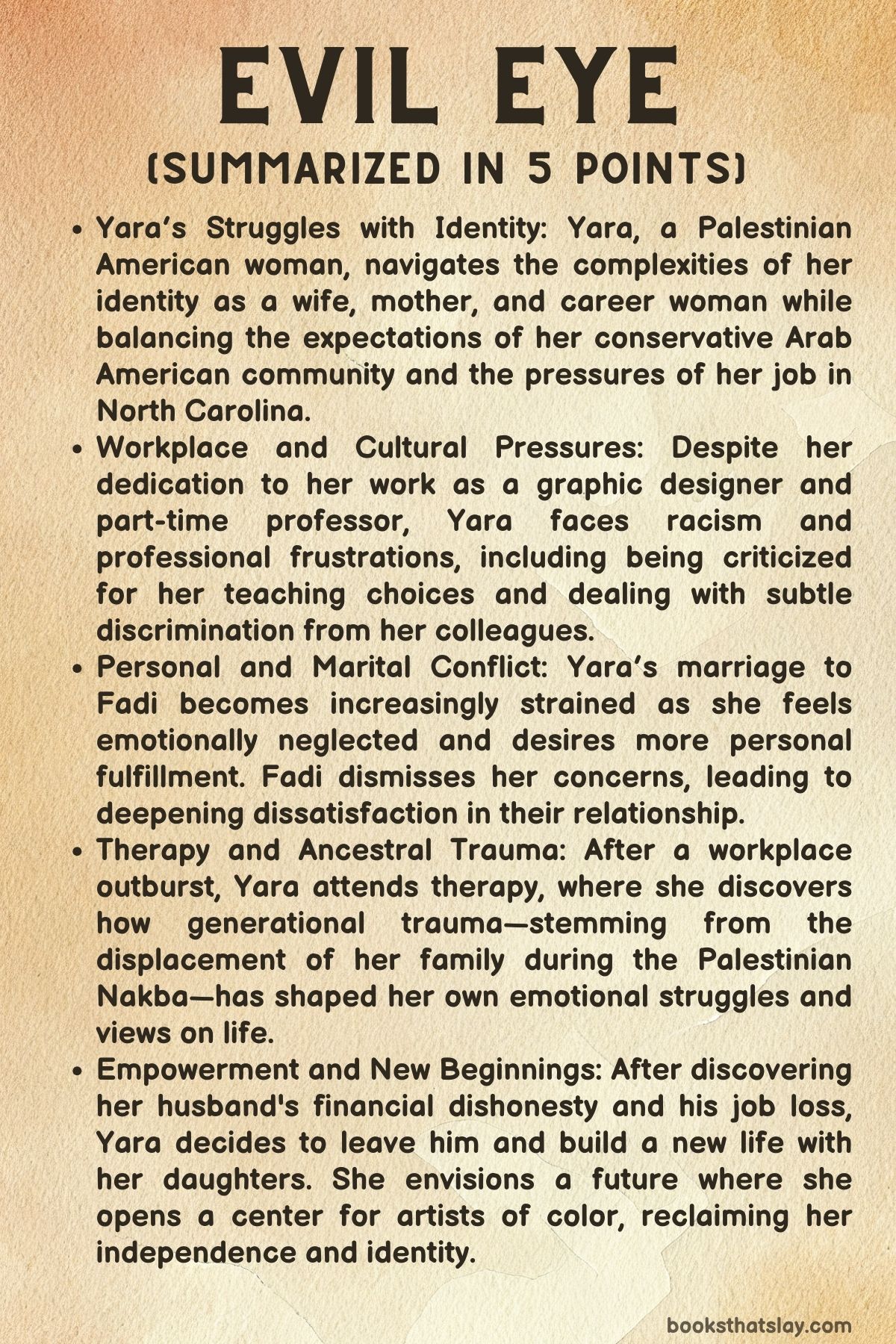

Evil Eye by Etaf Rum, published in 2023, is a compelling narrative about identity, generational trauma, and the struggle for personal autonomy. The novel follows Yara, a Palestinian American woman living in North Carolina, as she navigates her roles as a wife, mother, and professional while contending with the cultural expectations of her Arab American community.

Throughout the story, Yara grapples with the weight of ancestral trauma, her disintegrating marriage, and the deep-seated emotional scars from her past. Through moments of revelation and confrontation, Yara embarks on a transformative journey toward reclaiming her sense of self.

Summary

Yara, the central character in Evil Eye, is a Palestinian American woman juggling numerous responsibilities—wife, mother, graphic designer, and part-time art professor—while living in North Carolina.

She is married to Fadi, a small business owner, and together they have two daughters, Mira and Jude. Yara comes from a traditional Palestinian family in Brooklyn, raised with strict cultural norms. Her family’s history is marked by displacement, as both her own and Fadi’s relatives were forced from their homes in Palestine.

Though Yara works hard in both her career and family life, her efforts often go unappreciated, especially by her mother-in-law, Nadia, who questions why Yara pursues a career when she could focus solely on her family and community.

At work, Yara faces multiple frustrations. Although she is passionate about her teaching and graphic design, her position remains part-time, and she encounters subtle yet persistent racism from colleagues.

Her department chair even criticizes her for incorporating too many artists of color into her curriculum, adding to her professional stress.

The demands of her job, along with the pressures of being a wife and mother, leave Yara feeling exhausted and unfulfilled.

Yara’s home life is no sanctuary either. Her childhood was filled with dysfunction—her father was abusive, her mother struggled with mental health issues, and an affair within the family led to their ostracism from the community.

As an adult, Yara finds that although her marriage to Fadi is stable compared to her upbringing, it leaves her emotionally unsatisfied.

She longs for personal fulfillment through travel and a deeper connection to her career, but her attempts to discuss these desires with Fadi are met with defensiveness and anger.

He dismisses her concerns, accusing her of being selfish and comparing her to her mother, whose mental health struggles have left her stigmatized within the community.

Tensions come to a head when Yara, frustrated with her mounting pressures, lashes out at a colleague who makes a racist comment during a faculty meeting.

This outburst results in Yara being suspended from her teaching duties and required to attend therapy. Initially resistant, Yara forms an unexpected friendship with Silas, a gay professor, and gradually begins to uncover the roots of her emotional turmoil.

Her new therapist, Esther, introduces her to the concept of ancestral trauma, helping Yara connect her own struggles to the unresolved pain carried through generations, dating back to the Palestinian Nakba.

As Yara starts to confront her past and re-examine her life, she considers leaving her marriage. However, just as she prepares to tell Fadi of her decision, she learns he has lost his job.

She later discovers through Fadi’s business partner that her husband had been dishonest and misusing company funds. Determined to move forward, Yara proceeds with her plans for divorce, leaving Fadi and starting a new chapter with her daughters.

The novel concludes on a hopeful note, with Yara embracing her independence and envisioning a future where she opens a center for artists of color, finally feeling liberated from the weight of her past.

Characters

Yara

Yara is the protagonist of Evil Eye, and her character reflects the complexities of balancing multiple identities as a Palestinian American woman, wife, mother, and professional. Yara’s internal struggles revolve around her sense of duty to her family and community, her career aspirations, and her unresolved trauma from her dysfunctional childhood.

As a dutiful wife to Fadi and a mother to two children, Mira and Jude, Yara manages her household with skill. However, she feels suffocated by the expectations placed upon her by her family, particularly by her mother-in-law, Nadia, who disapproves of her working outside the home. Yara’s ambition to further her career as a graphic designer and part-time art professor is met with resistance, both from her family and from the predominantly white, racist academic environment in which she works.

Despite her competence and dedication, Yara is never offered a full-time teaching position and faces microaggressions from her colleagues. These external pressures, coupled with her strained marriage to Fadi, push Yara toward a breaking point.

Yara’s deeper conflict, however, stems from her childhood trauma. Her father was abusive, and her mother suffered from mental health issues, which were exacerbated by an affair that led their family to be ostracized from their Brooklyn Arab American community.

Yara’s unresolved trauma manifests in her feelings of inadequacy and dissatisfaction, even though her relationship with Fadi is relatively stable compared to her parents’ tumultuous marriage. Yet, Yara feels unseen by Fadi, who is dismissive of her desires and emotions, particularly when she tries to address their growing emotional distance.

Yara’s journey in the novel is one of self-discovery. Through therapy and her friendship with Silas, she confronts her past, understands the weight of ancestral trauma, and ultimately finds the strength to reclaim her sense of identity. By the end of the novel, she makes the bold decision to leave Fadi and pursue a new path, symbolizing her liberation from the roles that have long confined her.

Fadi

Fadi is Yara’s husband, and while he provides financial stability and a sense of security, he also represents the traditional expectations of marriage within their community. He runs a small business with a friend, though it is later revealed that his role in the business has been fraught with deception and financial mismanagement.

On the surface, Fadi seems like a supportive husband, but his inability or unwillingness to acknowledge Yara’s emotional needs causes a growing rift between them. He is defensive and dismissive when Yara tries to discuss their problems, particularly her desire for more fulfillment outside her roles as wife and mother.

Fadi’s perspective is heavily influenced by traditional gender roles and community expectations, and he often belittles Yara’s emotions by comparing her to her mother, whom he deems “crazy.” His refusal to engage in self-reflection and his attempts to suppress Yara’s growing need for independence ultimately drive her away.

He also embodies the inherited trauma of displacement, though he chooses to deal with it in silence, a contrast to Yara’s desire to confront and heal from the past. His final betrayal—losing his job due to dishonesty and mismanagement—cements the irreparable cracks in their marriage, pushing Yara to take the final step in reclaiming her autonomy by leaving him.

Nadia

Nadia, Yara’s mother-in-law, represents the more conservative, traditional values of their Palestinian community. She is critical of Yara’s decision to work outside the home, believing that a woman’s primary responsibility is to her family and her community.

Nadia’s disapproval of Yara’s career and personal choices adds another layer of pressure to Yara’s already strained existence. Her judgment stems from her own experiences of displacement and loss, as she was part of the generation of Palestinians forced to leave their homes and live in refugee camps after the Nakba.

Nadia’s expectations for Yara to conform to traditional gender roles are rooted in this history of loss and survival, where family unity and cultural preservation are seen as paramount. Despite her rigid views, Nadia’s character highlights the generational divide between herself and Yara.

While Nadia is a product of a more patriarchal and survival-oriented mindset, Yara’s generation grapples with balancing cultural heritage with individual aspirations in a more modern, Western context. Nadia’s criticism of Yara is harsh, but it is also indicative of the broader struggles many immigrant families face in maintaining their cultural identity while adapting to life in a different country.

Silas

Silas is a gay culinary arts professor who becomes an unexpected ally and friend to Yara during her time in therapy. Initially, Yara is skeptical of therapy, but her interactions with Silas help her to open up and begin the process of self-exploration.

Silas plays an important role in Yara’s journey toward self-realization, as he offers her a different perspective on life and helps her confront the unresolved trauma from her past. His character provides a much-needed counterbalance to the more conservative forces in Yara’s life, such as Nadia and Fadi.

He represents the potential for emotional freedom and self-acceptance. Through her friendship with Silas, Yara learns the value of vulnerability and begins to embrace the parts of herself that she has long suppressed. Silas encourages Yara to seek out a new therapist, Esther, who helps her explore the concept of ancestral trauma.

His presence in the novel also highlights the theme of solidarity between marginalized individuals, as both Silas and Yara face their own challenges in navigating identity, community, and personal fulfillment.

Esther

Esther is the therapist who introduces Yara to the concept of “ancestral trauma,” a turning point in Yara’s understanding of her own struggles. Esther’s role is crucial in helping Yara connect her personal pain with the larger historical and cultural context of her family’s displacement from Palestine.

Through her sessions with Esther, Yara begins to see how the trauma experienced by her ancestors, particularly the Nakba, has been passed down through generations, affecting her mother’s mental health and, by extension, her own.

Esther’s guidance allows Yara to view her pain not as an isolated experience but as part of a broader, inherited legacy of displacement and loss. Esther’s character serves as a catalyst for Yara’s transformation. By helping Yara process her trauma in a more holistic way, Esther empowers her to take control of her life and make the difficult decision to leave Fadi.

Esther’s introduction of the concept of ancestral trauma also underscores one of the novel’s central themes: the interconnectedness of personal and collective history, and the need to confront that history in order to heal.

Mira and Jude

Mira and Jude are Yara’s daughters, and though their roles are more peripheral in the novel, they are significant in Yara’s decisions and motivations. Yara’s desire to be a good mother and to provide a stable home for her daughters is one of the reasons she initially stays in her unhappy marriage.

However, as Yara begins to confront her trauma and realize the importance of living authentically, she understands that staying in a dysfunctional relationship is not the best example to set for her children. Her decision to leave Fadi is made not only for herself but also for Mira and Jude. She wants them to see a mother who is empowered and free rather than one who is oppressed and stifled.

Themes

The Intersection of Identity, Gender, and Cultural Expectations in Diasporic Communities

In Evil Eye, Etaf Rum explores the complex intersection between identity, gender, and the cultural expectations placed upon women in diasporic communities. Yara faces the burdens of navigating her identity as a Palestinian American woman living in a patriarchal society while also dealing with the expectations of her family and community.

As a daughter of displaced Palestinian refugees, Yara is deeply embedded in a cultural framework that venerates traditional gender roles, particularly the sacrificial roles of wife and mother.

Throughout the novel, her mother-in-law, Nadia, disapproves of her desire to work outside the home, representing the pressures exerted by older generations to conform to cultural norms.

Yara’s career as a graphic designer and part-time art professor is vital to her self-worth.

This tension reflects the broader conflict many immigrant women experience: balancing the preservation of cultural traditions with the pursuit of personal fulfillment in a modern, Western society.

The Legacy of Ancestral Trauma and Its Transgenerational Impact

One of the most profound themes in the novel is the exploration of ancestral trauma and its impact on subsequent generations. Yara’s personal struggles with mental health are revealed to be deeply connected to the trauma of her family’s displacement during the Nakba, the mass exodus of Palestinians in 1948.

Through her therapy sessions with Esther, Yara begins to understand the concept of “ancestral trauma”—the inherited psychological pain passed down through generations as a result of historical violence and displacement.

Her mother’s mental health issues and her father’s abusiveness are rooted in the trauma experienced by earlier generations of their family, who lived as refugees after being forcibly removed from their homeland.

Yara’s inability to feel whole or satisfied in her life is not solely the result of her personal circumstances but is inextricably tied to a much larger history of dispossession.

The novel deftly intertwines this personal narrative with the political, illustrating how the Nakba’s legacy continues to shape the emotional and psychological lives of Palestinian descendants.

Yara’s eventual recognition of this intergenerational burden allows her to break free from it, symbolizing the possibility of healing and self-determination for those haunted by ancestral trauma.

The Constriction of Female Autonomy in the Context of Marital and Familial Relationships

Yara’s struggles within her marriage to Fadi offer a poignant examination of how female autonomy is often constrained within marital and familial relationships, particularly in traditional communities.

While Yara initially believes that her relationship with Fadi is a step up from the dysfunctional marriage of her parents, she gradually realizes that her needs and desires are continuously subjugated to her husband’s.

Her longing for personal growth—both professionally and spiritually—is stifled by Fadi’s expectations that she conform to her role as a wife and mother, with little regard for her individuality. The novel uses the microcosm of their marriage to explore broader patriarchal structures that deny women the space to articulate their own desires.

Fadi’s dismissiveness, especially when he compares Yara to her mother, whom he deems “crazy,” encapsulates the way in which men often weaponize women’s mental health struggles as a means of control. His failure to understand Yara’s need for personal fulfillment beyond the domestic sphere ultimately leads to the dissolution of their marriage.

The narrative critiques the way societal and familial structures often trap women in cycles of dependency, forcing them to prioritize familial harmony at the expense of their autonomy.

The Psychological Toll of Microaggressions and Racial Discrimination in Professional Spaces

Rum’s novel also delves into the psychological toll of experiencing microaggressions and racial discrimination in predominantly white professional spaces. Yara’s career as a part-time professor is fraught with racist microaggressions from her white colleagues, who criticize her for including too many artists of color in her curriculum.

This professional discrimination mirrors the larger societal marginalization that Yara faces as a woman of color in America, where her competence and authority are constantly questioned. These microaggressions compound her sense of alienation and invisibility, both in her work and in her personal life.

When she finally lashes out during a faculty meeting, calling a colleague racist, the consequences she faces—suspension and mandated therapy—highlight the ways in which institutions often suppress the voices of marginalized individuals rather than addressing the underlying racism. The novel critiques how professional spaces that claim to be progressive can still perpetuate systemic discrimination, leaving individuals like Yara feeling powerless and erased.

The Interplay of Mental Health, Cultural Stigma, and the Need for Emotional Healing

The novel presents an intricate exploration of mental health, especially within the context of cultural stigma and emotional repression. Yara’s journey towards recognizing and addressing her own mental health issues is fraught with obstacles, not only due to the difficulties of her past but also because of the cultural norms that discourage the acknowledgment of psychological distress.

Her husband, Fadi, dismisses her attempts to communicate her emotional struggles, likening her to her mother, whose mental health issues led to the family’s ostracism. The novel highlights the damaging effects of such stigmatization, where mental illness is seen as a mark of shame, especially for women.

Yara’s reluctance to seek help initially reflects the internalized shame many individuals feel when confronting their mental health in communities that prioritize resilience and silence over vulnerability. However, her eventual embrace of therapy, and the discovery of ancestral trauma, represents a reclamation of her emotional well-being.

The novel suggests that healing can only begin when individuals like Yara break free from the cultural and familial taboos surrounding mental health, allowing themselves the freedom to confront their pain without fear of judgment.

The Quest for Creative and Spiritual Fulfillment Amidst Cultural and Familial Confinement

Finally, Evil Eye portrays Yara’s quest for creative and spiritual fulfillment as a metaphor for her larger struggle for autonomy and self-actualization. Her work as a graphic designer and part-time professor provides her with an outlet for her creativity, but it is not enough to satisfy her deeper, more spiritual longings.

The novel explores how the weight of her cultural and familial obligations prevents Yara from fully realizing her artistic ambitions and personal aspirations. Her dream of opening an artists’ center for people of color represents her desire to create a space for creative expression that transcends the limitations imposed on her by her family and community.

By the end of the novel, Yara’s decision to leave Fadi and move into her own apartment symbolizes her reclaiming of space—not just physical, but also emotional and creative—for herself. The novel ultimately argues that true fulfillment comes not from adhering to societal expectations, but from pursuing one’s passions and embracing one’s identity, free from the confines of external pressures.