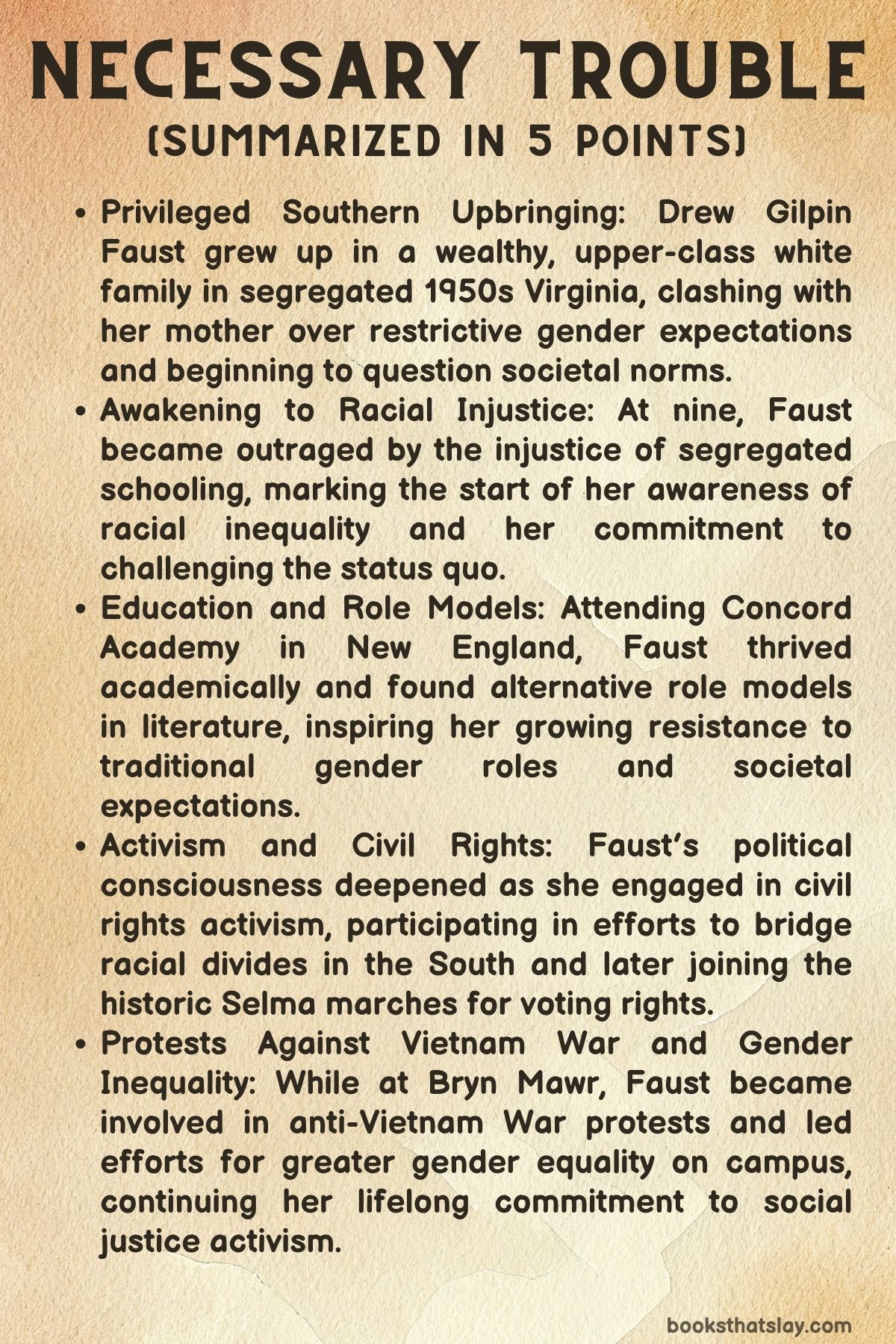

Necessary Trouble: Growing Up at Midcentury Summary and Analysis

“Necessary Trouble: Growing Up at Midcentury” by Drew Gilpin Faust is a compelling memoir that recounts the author’s formative years as a young girl navigating the complexities of race, gender, and social expectations in 1950s and 1960s America.

Born into a wealthy white family in Virginia, Faust reflects on her privileged upbringing and the moments that sparked her evolving awareness of racial injustice, inequality, and the rigid roles assigned to women. Through her experiences, Faust portrays her journey from a curious, defiant child to a socially conscious activist, eventually becoming one of the most influential historians of her generation.

Summary

Drew Gilpin Faust’s memoir Necessary Trouble paints a vivid picture of her upbringing in 1950s Virginia, where she was born into an affluent, upper-class white family deeply rooted in Southern tradition.

Although wealth had long defined her family, the economic shifts following World War II left them struggling to adjust.

This backdrop of fading privilege shaped much of Faust’s early years, particularly as her parents, who had grown up enjoying an opulent lifestyle, found it difficult to adapt to their new reality.

Faust’s mother, in particular, held tightly to old social norms, trying to enforce a rigid version of femininity upon her daughter, which only led to conflict between them.

From a young age, Faust challenged her mother’s expectations, particularly in comparison to her brothers, who were given more freedom.

The disparities in gender roles left her frustrated and determined to rebel against the constraints imposed on her as a girl.

Her mother, a woman who had been similarly shaped by societal expectations and limited opportunities, especially in terms of education, struggled to understand Faust’s desire for more than the life of a “proper lady.”

This tension at home highlighted for Faust the inequities embedded in the world around her.

Growing up surrounded by racial segregation, Faust was initially oblivious to the deeper implications of the system, accepting things like separate bathrooms and entrances for Black servants as normal.

However, a turning point came when, at nine years old, she heard about the push to desegregate schools on the radio. The realization that Black children were barred from attending her school shocked her into a new awareness of racial injustice, prompting her to write a letter to President Eisenhower, urging him to intervene.

This was the beginning of Faust’s critical questioning of postwar America’s ideals and contradictions.

As a teenager, Faust found refuge in literature, drawing inspiration from strong female characters like Nancy Drew and Scout Finch, who offered models of girlhood beyond the narrow confines of her upbringing.

At 13, she left home to attend Concord Academy, a progressive boarding school in New England, where she thrived in an intellectually challenging environment.

Despite still feeling the weight of gendered expectations, Concord offered Faust the space to explore her political ideas and allowed her to experience a different, more open discourse on racial issues.

One of her most formative experiences was hearing Martin Luther King, Jr., speak, sparking a deep commitment to civil rights.

Her commitment to activism deepened when she spent the summer of 1964 in the South, engaging in efforts to bridge racial divides during a time of intense polarization.

This experience solidified her dedication to the civil rights movement, which continued when she entered Bryn Mawr College.

Despite the school’s rigorous academic environment, Faust grew increasingly disillusioned with the disconnect between her education and the social and political turmoil gripping the country, especially after witnessing the violence of Bloody Sunday.

She participated in the Selma marches and anti-Vietnam War protests, becoming increasingly involved in both movements.

By 1968, the world seemed chaotic, with assassinations, wars, and protests dominating the headlines.

Faust, having fully embraced her activist identity, cast her vote in protest for Dick Gregory, recognizing the symbolic progress despite the ongoing struggles for equality.

Characters

Drew Gilpin Faust

Drew Gilpin Faust, the memoir’s central figure, serves as both the narrator and protagonist. She is portrayed as a highly intelligent and determined young woman, growing up in a wealthy, conservative Southern family during the mid-20th century.

From an early age, Faust is keenly aware of the social restrictions placed on her as a girl, and she rebels against the rigid gender norms her family imposes. Her refusal to conform to her mother’s expectations of femininity becomes a significant part of her identity.

Faust’s intellectual curiosity is evident throughout the memoir. She is deeply impacted by the civil rights movement and antiwar protests, which prompt her to question the social injustices around her.

Her sense of fairness is first sparked by learning about segregated schooling, and she continues to seek justice through her involvement in various social causes. By the time she reaches college, Faust has become an activist, torn between pursuing her education and devoting herself to the political movements of the 1960s.

Her journey from a privileged Southern girl to a socially aware, politically engaged young woman highlights her growth and self-awareness. Faust’s personal experiences reflect larger societal changes in America during the 1950s and 1960s, and her narrative underscores the intersection of gender, race, and class in shaping one’s identity.

Faust’s Mother

Faust’s mother is portrayed as a conservative and traditional figure who subscribes to strict notions of femininity. She represents the older generation’s adherence to rigid gender roles, believing that women should focus on being proper wives and mothers rather than pursuing education or independence.

Her insistence on turning her daughter into a “lady” creates conflict between her and Faust. Faust’s mother’s frustrations likely stem from her own limited opportunities, as she grew up wealthy but had few avenues for personal development outside the home.

Although she does not play an overtly antagonistic role, her worldview is emblematic of the stifling expectations placed on women in mid-century American society. Her relationship with Faust is marked by tension, as Faust resists the life her mother envisions for her.

Faust’s Father

Faust’s father, though less prominent in the memoir, embodies the patriarchal attitudes typical of the time. As the head of the family, he expects adherence to traditional roles, and his views align with the conservative, Southern values of their social class.

His role as a provider is central to the family’s identity, yet Faust notes the economic changes that followed World War II, which affected their upper-class status. He is more of a background figure, representing the societal structures that Faust ultimately seeks to challenge.

His permissiveness toward his sons, while restricting Faust’s freedom, further emphasizes the gender divide that Faust rails against.

Faust’s Brothers

Though not extensively explored in the memoir, Faust’s brothers symbolize the gender privileges afforded to men in her society. Unlike Faust, they are given freedom and independence from an early age, and they are not subjected to the same stringent expectations of proper behavior.

Their freedom becomes a source of resentment for Faust, who sees the disparity in how she and her brothers are treated by their parents. While the memoir does not delve deeply into their personalities or lives, they function as examples of how gender inequality manifests within families.

Black Servants

The Black servants in Faust’s household are a critical part of her early understanding of race and privilege, though they remain largely unnamed and in the background. Their existence in the household, using separate bathrooms and doors, exemplifies the systemic segregation of the era.

Faust’s lack of awareness of their second-class status as a child reflects the blindness of privilege. However, as she grows older and becomes more politically aware, Faust begins to question the racial hierarchies that had once seemed normal.

The servants serve as a stark reminder of the racial inequalities that Faust later dedicates herself to challenging, even if they do not play a central role in the memoir’s narrative.

The Teachers at Concord Academy

At Concord Academy, Faust is introduced to a new set of role models—her teachers. These women offer Faust an alternative model of womanhood, one where academic achievement and intellectual pursuits are valued.

However, the teachers at Concord are not entirely free from the traditional gender expectations of the time. Although they empower their female students in many ways, they still hold to the belief that economic responsibilities should be left to husbands.

The contradictions in their guidance reflect the transitional period of the 1960s, where progress for women was still constrained by lingering social norms. The teachers, nonetheless, play an important role in Faust’s intellectual development, encouraging her to think critically and independently.

Martin Luther King, Jr.

Though he appears only briefly in Faust’s narrative, Martin Luther King, Jr. represents a powerful and inspiring figure in her political awakening. Faust recalls hearing him speak while at Concord Academy, an experience that deeply impacts her view of the civil rights movement.

King’s leadership and his nonviolent approach to activism resonate with Faust’s developing sense of justice. His influence is a driving force behind her decision to join the civil rights movement herself.

King serves as a symbol of the broader struggle for racial equality, a cause that becomes central to Faust’s activism.

Faust’s Boyfriend

Faust’s unnamed boyfriend plays a supporting role in her journey into political activism. He accompanies her to Selma to participate in the voting rights march, indicating that their relationship is founded on shared values of social justice.

His presence in the narrative emphasizes the importance of collective action and partnership in political movements, though his character is not deeply explored. The relationship underscores the growing radicalization and political engagement of Faust and her peers during the turbulent 1960s.

Through these characters, Necessary Trouble provides a rich examination of the social forces that shaped Drew Gilpin Faust’s identity. Her memoir highlights the conflicts between tradition and progress, and her personal evolution mirrors the broader societal shifts of mid-century America.

Themes

The Struggle Between Individual Identity and Societal Expectations of Gender Roles

Drew Gilpin Faust’s memoir intricately examines the deep conflict between personal identity and the rigid gender norms that defined midcentury America. Growing up in a conservative Southern family, Faust was subject to her mother’s strict expectations for what it meant to be a “proper” woman, a notion largely defined by the roles of wife and mother.

These gender expectations were entrenched in a patriarchal social system where women’s ambitions were limited and their worth confined to the domestic sphere.

Faust’s early rebellion against these norms manifests in her resentment towards the freedom her brothers enjoyed and her own limitations, which she felt were arbitrary and unfair.

This rebellion is not just against her mother, but against a broader cultural script that dictated the shape of femininity in postwar America.

Faust’s desire for intellectual and personal autonomy led her to resist this script, as she found empowerment in intellectual pursuits, such as her fascination with literature and her academic success.

Her time at Concord Academy exposed her to a new set of possibilities, yet even there, the institution’s encouragement for women to be both intellectually rigorous and “ladylike” underscored the pervasive grip of traditional gender roles.

Faust’s journey through adolescence and early adulthood highlights the tensions between society’s expectations and her determination to forge a self that is defined by her own values, beliefs, and intellectual pursuits, rather than by the narrow definitions of womanhood that dominated her upbringing.

Privilege, Race, and the Moral Awakening of a Southern Elite

One of the most compelling themes in Necessary Trouble is Faust’s grappling with her own privilege as a white, wealthy Southerner raised in a segregated society.

The rigid racial hierarchies of 1950s Virginia were, for a time, invisible to the young Faust. Black servants used separate entrances and bathrooms, their presence a constant but unexamined part of her world.

The moment of realization at the age of nine, when Faust learns about school segregation from the radio, marks the beginning of her moral awakening.

Faust’s shock at this injustice demonstrates her early commitment to questioning the societal norms that she had previously taken for granted.

This theme unfolds throughout her memoir as she transitions from passive acceptance of her inherited privilege to active engagement in civil rights.

The sharp contrast between her sheltered upbringing and her later involvement in the civil rights movement illustrates the moral and intellectual journey she undertakes.

Her trip through the American South, working with a racially mixed group to support racial integration, forces Faust to confront the entrenched divisions and polarization that defined the region and, in many ways, her own childhood.

The memoir explores how her class and race privilege intersect with the burgeoning awareness of systemic inequality, leading her to a deeper understanding of her own place within these structures and the necessity of challenging them.

This tension between privilege and morality is central to Faust’s personal evolution, reflecting broader national struggles around race and class during the mid-20th century.

The Role of Education as a Catalyst for Political and Social Consciousness

Education is portrayed not merely as an intellectual exercise in Faust’s memoir but as a profound mechanism for political and social consciousness.

From her early years, Faust finds solace in books, identifying with characters like Scout Finch and Nancy Drew, who represent strong, inquisitive girls challenging societal norms.

Her enrollment at Concord Academy becomes a pivotal moment in her life, providing her with an intellectual community where she is encouraged to think critically and question prevailing societal structures.

However, her experience at Concord is not without tension.

While she is exposed to more progressive ideas, including the open discussion of racial inequalities, the institution still subtly endorses traditional gender expectations, reflecting the slow pace of change in even the most forward-thinking environments.

Faust’s subsequent journey to Bryn Mawr further sharpens this theme, as the college provides an intellectually rigorous space for women, yet remains disconnected from the urgent social movements of the time.

Faust’s frustration with the irrelevance of some of her academic studies in light of the pressing civil rights and antiwar issues underscores the complex relationship between formal education and the real world.

Her use of research papers as a tool for exploring political topics demonstrates her determination to bridge the gap between academic life and activism.

Education, in Faust’s view, becomes a double-edged sword: it offers the tools for critical thought and moral clarity, yet often remains disconnected from the pressing realities of social justice.

Faust’s evolving relationship with education reflects a broader tension in midcentury America, where intellectual institutions were slow to catch up with the seismic cultural and political shifts occurring around them.

The Collision of Historical Forces and Personal Development

The memoir is also an exploration of how historical forces shape personal identity and growth. Faust’s coming-of-age unfolds against the backdrop of some of the most turbulent events in modern American history—the civil rights movement, the Vietnam War, the assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Robert F. Kennedy, and the rise of student protests.

These events do not simply occur in the background of her life; they are catalysts that drive her personal development.

Her trip to communist Eastern Europe, for instance, reveals the complexity of global politics in ways that challenge the simplistic narratives she had been taught, broadening her worldview and heightening her awareness of the interconnectedness of political systems.

The civil rights movement, in particular, is a defining historical moment that intersects deeply with her own moral awakening.

Faust’s participation in the iconic march in Selma connects her individual desire for justice with the broader struggle for racial equality, illustrating how national movements for social change can influence personal trajectories.

Similarly, the Vietnam War’s impact on young men she knew and the increasing violence of antiwar protests draw her into the movement, compelling her to question not only U.S. foreign policy but also the ethical responsibility of citizens in the face of state-sanctioned violence.

Faust’s personal development cannot be understood apart from these historical forces; her memoir illustrates the intricate ways in which individual identity is molded by the larger cultural, political, and social upheavals of the time.

The Limits of Activism and the Search for Personal Relevance in an Era of Radical Change

Faust’s involvement in the civil rights and antiwar movements reflects a deep commitment to activism, but her memoir also engages with the theme of disillusionment and the limitations of activism.

While her participation in the Selma march and her work with civil rights groups gave her a profound sense of purpose, Faust also grapples with the realization that change was not as immediate or sweeping as she had once hoped.

Her reflection on her “astonishingly naïve” efforts to foster racial understanding in the South underscores the complexities and difficulties of achieving genuine social progress. This sense of disillusionment carries over into her antiwar activism, where the initially peaceful protests against the Vietnam War grew increasingly violent, prompting Faust to question the efficacy of such demonstrations.

As the decade wore on and the movements became more fractured, Faust began to shift her focus toward more localized victories, particularly in the context of gender equality at Bryn Mawr. The Sexual Revolution on campus became a domain where Faust could see tangible progress, leading to greater gender equality in everyday life.

This shift from grand political movements to more personal victories reflects a broader theme in the memoir: the search for relevance and impact in an era of radical social change. Faust’s journey is not one of unqualified success in activism, but rather a nuanced exploration of the limits of what can be achieved through collective action, and the importance of finding personal meaning and relevance in a world that often feels chaotic and overwhelming.