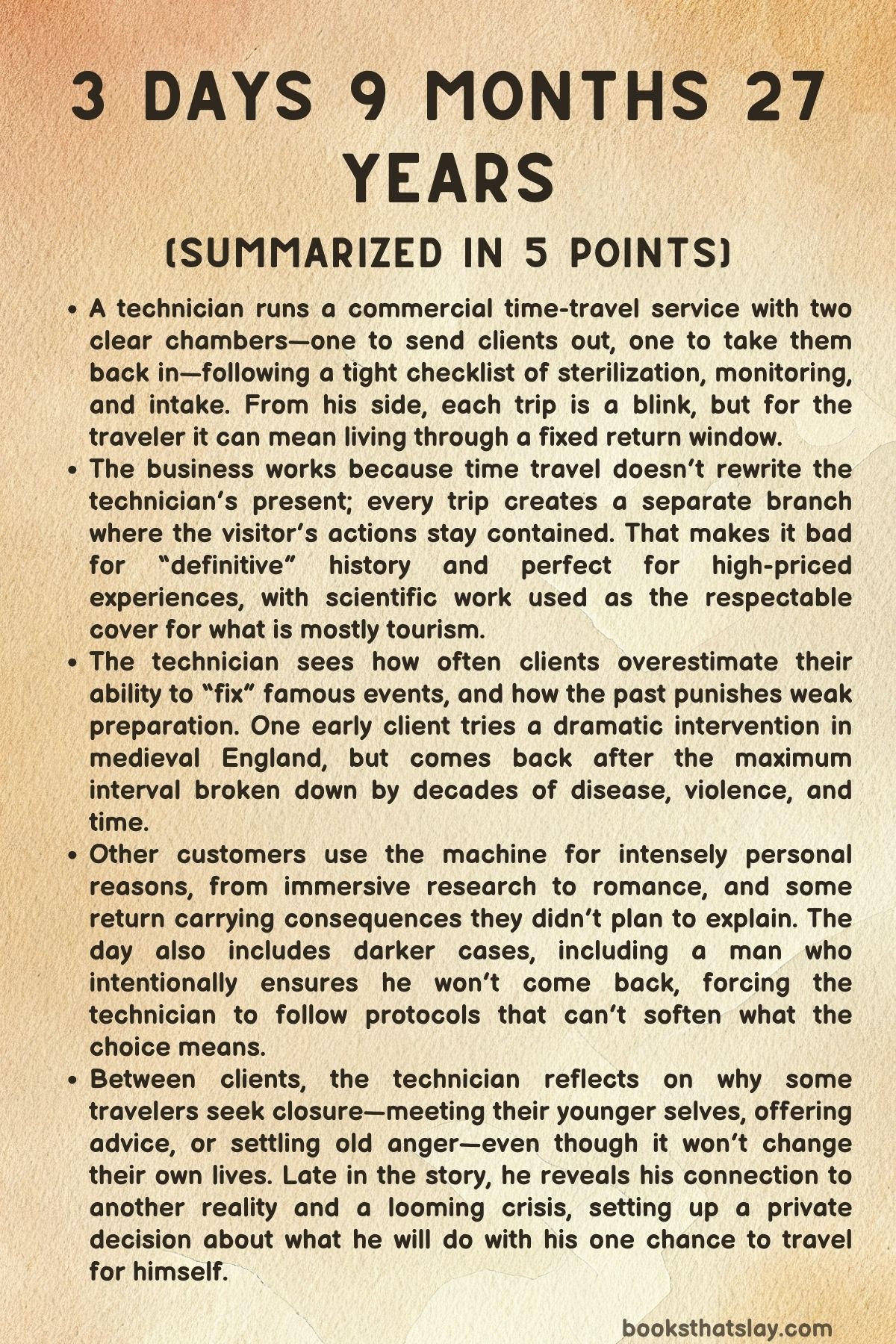

3 Days 9 Months 27 Years Summary, Characters and Themes

3 Days 9 Months 27 Years by John Scalzi is a science-fiction story told by a weary technician who runs a commercial time-travel service. In his workplace, time travel is not a heroic mission to “fix” history; it’s a product, complete with sterilization protocols, liability waivers, and customers chasing fantasies.

The twist is that every trip creates a new branch reality, so nothing a traveler does can change the technician’s present. Across a single workday, he processes clients who want to rewrite empires, find love, escape life, or simply take a quiet break—until he admits the job is personal. He has already lived through one doomed world.

Summary

A technician describes his daily job operating a commercial time machine. The device is built around two clear chambers: one for departure and one for return, connected by portals that look immediate from the operator’s side.

His routine is procedural and clinical—prepare clients for sterilization, confirm their gear and paperwork, monitor the step through the portal, and be ready to receive them when they come back. To him it feels like customers vanish and reappear in moments, but for them the trip can last a long time.

Even with standard safety checks, he knows the process is unpredictable, and “normal” returns are never guaranteed.

The foundation of the business is a rule that makes time travel marketable: it does not change the technician’s own reality. Each trip creates a separate branch, a new offshoot timeline.

Travelers can interfere with whatever era they visit, but it only affects that branch. When they return, they come back to the same present they left, and whatever happened in the branch becomes inaccessible.

This discovery removed the fear of paradox and turned the machine into a tourism engine. Clients are called “temponauts,” and they buy trips for reasons that range from research and curiosity to obsession and self-destruction.

The technician explains that returns are constrained by set “retrieval intervals.” The most common are three days, nine months, and twenty-seven years. Those are the windows the system can reliably lock onto to pull someone back.

Longer options exist, but they are impractical for a commercial operation. The twenty-seven-year interval is the final workable return point; if someone does not come back then, the company treats them as a non-return.

The first client of the day is an accountant convinced he can improve history. He intends to go to 1066 and assassinate William the Conqueror using a sniper rifle, believing he can prevent the Norman conquest of England.

The technician has seen many versions of this ambition: customers with neat plans to kill a famous person, save another, or “correct” a turning point. The accountant steps into the portal with confidence.

When he returns, the fantasy collapses into biology and time. The accountant has spent the full twenty-seven years on the other side.

He comes back aged far beyond what anyone expects from a short-looking trip, and he is in terrible condition—ravaged by illness, injury, and the accumulated punishment of surviving in a past that does not care about modern intentions. Medical staff sedate him and move him out quickly.

The technician notes the cruel irony: customers imagine time travel as a shortcut to a goal, but the machine’s rules often make the cost literal decades of living, with all the violence, infection, and misfortune that can come with it. Whether the accountant succeeded is impossible to know.

Even if he did, it happened in a branch reality that no longer connects to this one.

That separation between realities reshaped the value of time travel. It made the technology nearly useless for historians who want “the” past, because any human presence changes events and spins off a new history.

Observation is contamination. Still, the technician acknowledges there are scientific uses: a traveler can retrieve data from before their arrival in the branch—samples, measurements, extinct DNA, readings of astronomical events—things that existed prior to interference.

But human-centered outcomes become unreliable the moment someone steps into an era and interacts with it. Once scholars accepted that limitation, the machine’s future belonged to commerce.

Governments objected at first, but the company argued that tourist money funded legitimate science, and a mixture of lobbying and quiet payoffs kept regulators manageable.

The second client is a novelist who uses the service as a research tool. She often visits eighteenth-century Sri Lanka to build her setting and details firsthand.

The technician recognizes her as a repeat customer who knows the procedures and the risks. On this trip, however, she returns with something that cannot be treated as a simple souvenir: she is pregnant.

She admits she fell in love with a merchant in that era and chose to have his child. The technician registers the fact with the same practiced neutrality he uses for injuries or contraband.

Time travel has become a way for people to pursue private lives in worlds that will never intersect with the one they came from, and he has learned that judging clients does not change what they are going to do.

Between customers, he reflects on how most grand plans fail. People who try to rescue public figures or remove villains usually underestimate how protected those figures are, even in eras that look chaotic from textbooks.

Others misunderstand the economics of time: they dream of making investments in the past and returning rich, only to discover that profit requires patience, infrastructure, and long-term stability they cannot maintain as outsiders. Many temponauts are unprepared for languages, disease, weather, and social systems that do not offer second chances.

The company’s contract warns them, but it also shields the company from responsibility. Online forums amplify the rare success stories while burying the many disasters, creating a distorted confidence in newcomers who want to believe they will be the exception.

The third client travels to the Late Cretaceous period. As he approaches the portal, he deliberately drops his survival pack and steps through without it.

The technician recognizes the act for what it is: a planned suicide, dressed up as an exotic adventure. He triggers the required alarms and completes a non-return report, following protocol.

He has seen this choice before—clients who want their ending to be dramatic, ancient, and far from the quiet decline they fear in their own lives. Sometimes, long after the fact, remains or traces appear in strange ways, aged by centuries, confirming that someone died alone in a branch reality no one can reach.

Not every client is so extreme. The technician processes travelers who want low-impact trips: a peaceful vacation, a brief escape, a carefully controlled experience with minimal interaction.

These are easier, safer, and more likely to end with a healthy return. There are also clients who want something emotionally specific, like meeting their younger selves.

They know they cannot change their own timeline, but they hope to give advice or a warning to an alternate version of themselves. The technician has watched people come back relieved, angry, or strangely satisfied.

One person even used the machine to go back and punch his younger self, returning with the calm of someone who finally acted out a long-held impulse.

In the final stretch, the technician reveals that he is not native to this reality. He came from another branch where humanity was collapsing under a mass die-off triggered by layered global crises.

In that world, he held authority as an acting director in the organization connected to the time-travel program. When the situation became hopeless, he used the maximum interval—twenty-seven years—to jump into a slightly earlier reality and deliver warnings that might prevent the catastrophe here.

He met his younger self, shared information, and then stayed, taking a new identity and settling into the technician’s role. His goal was not fame; it was to push this timeline away from the cliff he already watched his own fall off.

But his intervention only bought time. The same disaster is now approaching in this reality, and it is close—only weeks away.

He knows the patterns, knows what comes next, and knows he cannot stop it. The job that once seemed like detached customer service is now a front-row seat to a repeating end.

With the collapse imminent, he decides to finally use the employee benefit he has postponed for years: one free trip to any time. He prepares himself with the same steps he performs for everyone else, but now he is both operator and customer.

He no longer believes in saving the world, and he does not pretend he can carry a whole civilization on his back. Instead, he wants something simpler and rarer than heroism: rest.

He accepts that realities can branch endlessly while he remains the same person moving between them. Then he steps toward the portal, leaving behind a dying timeline, and chooses to begin again somewhere else, not to fix history, but to find peace.

Characters

The Technician Narrator

The narrator is the steady, controlled voice at the center of 3 Days 9 Months 27 Years, a professional whose calm routines hide a life shaped by unbearable knowledge. On the surface, he is a technician running a commercial time machine with the practiced detachment of someone who has seen every kind of human impulse come through a doorway—ambition, grief, thrill-seeking, denial, and despair.

His job demands procedural precision and emotional restraint: he sterilizes clients, monitors departures, receives the returned, and documents failures without getting pulled into the moral chaos of what people do when they are given access to the past. Yet that restraint is not indifference; it reads more like a survival skill built over time, because he understands better than anyone that time travel here is not a “fix,” but a fork—every journey births a separate reality and severs the traveler from the origin world in any meaningful, verifiable way.

What ultimately deepens him from observer to tragic participant is the revelation that his neutrality is partly a performance. He is not merely someone who watches others chase meaning; he once tried to create meaning through intervention himself.

He originates from a different reality that succumbed to a slow, cumulative collapse, and he used the longest viable retrieval interval—twenty-seven years—to move into a slightly earlier branch with the hope of changing outcomes. His choice to become a technician under a new identity turns him into a man living inside his own failed contingency plan: he did not stop catastrophe, he only delayed it, and now he must face the same approaching end again.

The emotional engine of his character is that he lives with “branching” not as a concept but as a personal sentence—worlds diverge and die, and he remains the one constant carried forward. By the end, his final decision to take his one employee trip is not escapism in the shallow sense but a surrender to the limits of agency in this system: if he cannot save timelines, he can at least choose the manner of his exit, seeking peace rather than one more futile attempt at heroism.

The Accountant

The accountant represents the most common fantasy the time travel business quietly feeds: the belief that history is a lever and that a single decisive act can redirect the world. He arrives with a plan that sounds clean and rational—assassinate William the Conqueror in 1066 to prevent the Norman conquest—framed like a problem with an elegant solution.

His profession matters symbolically: an accountant is trained to balance outcomes, forecast consequences, and treat the world as something measurable, as if historical cause-and-effect can be reconciled like a ledger. The story uses him to expose how badly that mindset misreads the past and the technology itself.

Even before the moral implications land, the practical reality does: the past is harsh, survival is uncertain, and the retrieval intervals are merciless.

His return in a grotesque condition—aged, mutilated, diseased, and having endured the full twenty-seven-year span—turns him into a cautionary spectacle. He embodies the gap between intention and consequence: he likely imagined a quick in-and-out mission, but the machine’s “instant” perspective for the operator hides the human cost paid on the traveler’s side.

Whether he succeeded is deliberately unknowable because realities seal off after return, which makes his entire premise—changing “our” history—fundamentally misguided. That ignorance is the final cruelty of his arc: even if he did the thing he risked everything for, he will never have proof that it mattered, and the world he returns to cannot validate or be altered by it anyway.

He becomes less an individual than an example of how the service sells empowerment while the universe’s rules quietly ensure that empowerment is mostly illusion.

The Novelist

The novelist is a counterpoint to the accountant because she approaches time travel not as conquest but as immersion, and she treats the past less like a battleground for grand outcomes and more like a place where a life can be lived. She repeatedly visits eighteenth-century Sri Lanka for “research,” yet her repeated returns suggest that research is only the socially acceptable framing for a deeper longing: she has found not only detail for her work but also intimacy, belonging, and romance.

When she returns pregnant, the story reveals how time travel destabilizes not just history but identity—she is no longer simply a visitor collecting material; she is a woman carrying a future that can only exist because she crossed into an alternate branch.

Her pregnancy also forces a confrontation with what “tourism” really means when the destination contains real people. She falls in love with a merchant, chooses to bear his child, and in doing so turns the supposedly controlled, commercial experience into an irreversible personal transformation.

The technician’s lack of overt judgment matters: it shows that the company culture has normalized even the most profound entanglements as just another client outcome to process. Unlike travelers chasing famous names or wealth, she is motivated by relationship and meaning, and that makes her both sympathetic and unsettling—sympathetic because she chooses love over spectacle, unsettling because she demonstrates how easily the past becomes a resource for the present’s needs.

Her character suggests that the most powerful “historical interventions” are not assassinations or fortunes but private choices that rewrite a person from the inside, even if the wider world remains untouched.

The Suicide Traveler to the Late Cretaceous

The third client is defined less by personality on the page and more by the stark clarity of his intention. By deliberately dropping his survival pack before entering the portal to the Late Cretaceous, he turns time travel into a method of self-erasure—choosing not just death, but death in a place and time so alien that it feels like annihilation plus spectacle.

His act exposes one of the business’s darkest truths: when you sell access to any era, you also sell access to dramatically staged endings. The technician’s response—alarms, paperwork, a non-return report—shows how institutional procedure can swallow even an obvious suicide, reducing a final human act to compliance steps and liability protocols.

What makes this character disturbing is that his choice is not impulsive; it is staged with intention, using the mechanics of the system as a tool. The mention that some non-returners’ remains later reappear centuries-aged reinforces the grim physicality behind the abstraction of “branches.” In a world where people fear quiet oblivion in their own lives, this traveler chooses an ending that feels historically grand, as if dying in the deep past can turn personal despair into something mythic.

He functions as a mirror held up to the entire enterprise: time travel tourism is not only about curiosity or adventure; it can also be a marketplace for controlled catastrophes, letting people curate their disappearance.

The Low-Impact Vacation Traveler

This client exists to show the other side of the industry: time travel as escapism without delusions of rewriting the world. The low-impact traveler wants something simple and human—a peaceful vacation in another era—treating time travel like an exotic resort rather than a revolution.

In a story packed with catastrophic outcomes and existential dread, this person embodies the seductive normalcy that makes the business viable. Their presence underlines that most customers are not trying to become saviors or monsters; they are trying to feel refreshed, to step outside their routines, to borrow a different sky for a while.

At the same time, the ease with which the technician handles such clients highlights the moral numbness that can develop around extraordinary technology. Low-impact travelers are “easy,” they usually return unharmed, and that reliability encourages the illusion that the system is benign.

Yet even this kind of travel still creates a new branch, still alters a world by mere presence, and still turns history into a consumable experience. The low-impact traveler’s function is therefore quietly unsettling: they show how a universe-changing act can be treated like leisure, and how the extraordinary becomes ordinary once it is packaged, priced, and scheduled.

The Self-Meeting Advice Givers

These travelers are driven by a uniquely human hunger: the desire to speak to the version of oneself that still had choices, still stood at forks before regret calcified. They go back to meet their younger selves not to alter their own past—because the rules prevent that from affecting their origin—but to offer warnings, encouragement, or hard-earned perspective to an alternate self who can still be saved from certain pains.

This is time travel as emotional repair rather than historical manipulation, and it reveals how the branching-reality model does not eliminate the impulse to fix things; it only redirects it from the public sphere to the private one. Their journeys are acts of compassion, mourning, and sometimes selfishness all at once: compassion for the younger self, mourning for what was lost, selfishness in seeking closure even when it cannot “count” for the traveler’s own life.

These characters also emphasize a subtle ethic the story keeps returning to: if you cannot change your own timeline, you might still change someone’s life in another. That possibility becomes a strange kind of consolation, and the very fact that people keep making these trips suggests that consolation is enough.

The technician’s observations about these meetings being emotionally satisfying reinforces the idea that meaning is not measured solely in causal impact; it can exist as a felt resolution, even if it echoes only inside a branched-off world.

The Client Who Punches His Younger Self

This traveler is a darkly comic variation on the self-meeting impulse, showing that confronting your past is not always tender or instructive—it can be punitive, cathartic, and absurd. By traveling back solely to punch his younger self and returning satisfied, he distills a complicated psychology into a single crude gesture: sometimes what people want is not wisdom or reconciliation, but revenge on the person they used to be.

The humor works because it is instantly recognizable; many people fantasize about shaking sense into their younger selves, and this character literalizes that fantasy with physical violence.

Yet the comedy has a bite. In a world where the technology cannot fix your own past, even vengeance becomes a substitute for change.

The punch does not heal the traveler’s timeline, but it gives him the sensation of closure, as if he has finally “paid back” the naïve, arrogant, or reckless self who set his suffering in motion. This character shows how time travel, even stripped of paradox, can still become a theatre for unresolved emotion—anger turned into an itinerary item, regret turned into a customer experience.

The Medical Technicians and Company Apparatus

While not individualized, the medical technicians and the broader company system operate like a collective character—an institutional personality built from protocols, contracts, alarms, sedation routines, and liability shields. They represent the world’s adaptation to the impossible: rather than treating time travel as sacred or terrifying, they treat it as an industry with workflows.

The medical staff who sedate and remove the returned accountant are the story’s reminder that the human body is the final battleground of this technology; no matter how sleek the chambers look, the traveler’s return can be a medical crisis that must be handled quickly and without sentiment.

The company itself functions as an engine of normalization and moral outsourcing. It warns clients, absolves itself of responsibility, tolerates personal entanglements, processes suicides, and justifies its existence by pointing to scientific side benefits, all while profiting from the endless human desire to step outside the present.

This apparatus does not need to twirl a villain’s mustache to be unsettling; its banality is the point. It is the structure that allows extraordinary harm and extraordinary longing to be converted into paperwork, revenue, and routine—making it possible for the technician narrator to stand at the center of wonders and horrors and still call it “a day at work.”

Themes

Commercialization of the impossible

A private company turns time travel into a service job, and that choice shapes everything that follows. In 3 Days 9 Months 27 Years, the two-chamber machine, the sterilization routines, the paperwork, and the strict “retrieval interval” rules make the extraordinary feel like airport security: controlled, repeatable, and optimized for throughput.

This framing matters because it shows how quickly human society converts wonder into a market, even when the product carries extreme risk. Clients are rebranded as “temponauts,” a word that softens what they are actually doing: stepping into environments where disease, violence, language barriers, and simple bad luck can destroy them.

The business model relies on a careful moral maneuver. By claiming that each trip creates a separate branch of reality, the company presents paradox-free travel as ethically clean and politically manageable, then uses contracts and liability waivers to place the consequences entirely on the customer.

That combination—technical safety for the operator’s timeline, legal safety for the firm, and physical danger for the traveler—reveals a system where profit can coexist with tragedy without forcing institutional self-reflection. Even government resistance collapses under lobbying and bribery, which exposes how regulation struggles when a technology is both lucrative and framed as inevitable progress.

The technician’s calm professionalism underlines how normalized this has become: disasters are processed as incidents, not moral crises. The theme is not only that capitalism can sell anything, but that it can sell the fantasy of significance—“go matter in history”—while quietly earning revenue from predictable failure and human desperation.

The futility of controlling outcomes

Time travel is commonly imagined as a tool for fixing mistakes or steering history, but the structure here strips that fantasy down to its emotional core: the desire remains, the effectiveness disappears. Because every journey produces a new reality, grand plans to “correct” the past lose their promised payoff.

The accountant who aims to assassinate William the Conqueror embodies this mismatch. He treats history like a problem that can be solved with a rifle and determination, yet his return—aged, mutilated, diseased—shows that the true challenge is not the target but surviving the world you enter.

Even if he succeeds, no one can confirm it, and his original reality cannot benefit. That uncertainty makes hero narratives collapse into private suffering.

The same logic undermines other familiar schemes: saving famous figures, killing villains, making investments, or bringing back proof for historians. The technician’s explanation that observation itself changes events pushes the point further: the moment a traveler arrives, the neat “known” past ends and an untrusted alternate begins.

The only reliable gains are narrow, carefully defined ones, such as collecting data that existed before the traveler’s presence—extinct DNA, astronomical readings—things that do not depend on controlling people. This theme becomes sharper through the narrator’s own backstory.

He traveled with warnings meant to prevent extinction, achieved a delay, and still failed to stop the overall collapse. That arc argues that control is often partial even when knowledge is vast and intentions are sincere.

The world is not a mechanism with one correct adjustment; it is a pile of interacting pressures that can absorb “fixes” and continue toward disaster. What remains, then, is not mastery but the ongoing human refusal to accept limits, even when the system guarantees those limits.

Risk, bodily cost, and the thin comfort of procedure

The story repeatedly emphasizes that the body is the real battleground of time travel. The machine may be transparent and clinically managed, but the traveler’s experience is not sterile; it is endurance.

The retrieval intervals are described as simple scheduling constraints for the operator, yet for the client they are a cage. A person can return in three days, nine months, or twenty-seven years, and the last option reads like a hard wall: if you miss earlier returns, you may be forced to live decades in hostile conditions until your final extraction.

The accountant’s ruined state is not just shock value; it is a demonstration that planning and equipment do not defeat infection, malnutrition, injury, aging, and psychological strain. The company offers sterilization and survival packs, but those are symbolic assurances compared to the reality of living in an era without antibiotics, predictable shelter, or safe social standing.

Procedure becomes a kind of emotional anesthesia for everyone involved. The technician follows checklists, triggers alarms, files reports, and watches medical teams sedate wrecked clients, and the repetitive nature of these actions reveals how bureaucracy can make catastrophe manageable enough to continue.

There is also a darker implication: when suffering becomes routine, institutions learn to treat it as a cost of doing business. The occasional reappearance of remains “centuries aged” underscores that even death can be processed as paperwork, a delayed artifact of a customer decision.

Yet the story does not present this only as corporate coldness. It shows a coping strategy for workers who must function beside horror without collapsing.

The technician’s restraint—observing without judgment, staying in role—reflects how people create emotional distance to survive their jobs, especially when their jobs involve irreversible outcomes. The theme lands as a blunt contrast: clean machines and clean language cannot clean up what the past does to human flesh.

Escape, longing, and the search for personal meaning

Many clients are not chasing historical impact at all; they are chasing feelings they cannot reach in their own era. The novelist who repeatedly visits eighteenth-century Sri Lanka and returns pregnant makes this theme explicit.

Time travel becomes a way to find romance, identity, and a sense of being truly present, even when the choice carries consequences that cannot be neatly integrated into modern life. Her decision is not framed as scandal or triumph; it is simply a human act, one that complicates the idea that time tourism is frivolous.

For her, the past is not a museum but a place where her life finally aligns with her desires. Other customers pursue closure rather than change: meeting a younger self to offer advice, to warn, or even to punch him.

Since these meetings cannot alter the traveler’s own timeline, their value is emotional rather than practical. They provide the satisfaction of saying what was never said, of releasing anger, of performing a private ritual of reconciliation.

The “low-impact” vacationers who want a peaceful break show another angle: time travel functions like the ultimate getaway, a way to step outside the pressures of the present without trying to rewrite history. But the theme also includes the bleakest form of escape: the man who drops his survival pack and steps through, choosing death.

That act reframes time travel as a doorway not to adventure but to disappearance, a way to exit existence with drama instead of fading quietly. Across these cases, the story suggests that when a technology opens impossible options, people use it less for grand projects and more for intensely personal needs—love, regret, rage, rest.

In that sense, time travel becomes a mirror that reflects what the present is failing to provide.

Moral distance and the ethics of “it doesn’t affect us”

Branching realities create a convenient moral argument: because the traveler’s actions do not change the operator’s world, the ethical stakes appear lower. That logic supports the entire industry, but the story keeps showing why it is emotionally and philosophically unstable.

Saying “it won’t affect our timeline” does not erase the fact that a traveler enters a real world with real people and can cause harm, disruption, or exploitation. The company’s posture—warnings in contracts, denial of liability—leans on this distance to avoid responsibility, while clients often lean on it to justify reckless behavior.

Assassination attempts, profit schemes, and casual interference become easier to rationalize when the traveler treats the destination as a disposable branch. At the same time, the story complicates judgment by showing that moral distance also enables compassion.

The technician refuses to condemn the novelist’s relationship or the strange catharsis of meeting one’s younger self, because he understands that the outcomes belong to that branch and to the traveler’s conscience. The ethical ambiguity intensifies with the narrator’s origin: he is literally a person displaced from another reality, living under a new identity, carrying knowledge of extinction.

His presence proves that these branches are not abstract; they are lived worlds with their own tragedies. When he warns another version of humanity, he is not saving “his” world, yet he is still acting out of care and responsibility.

That tension exposes the central ethical trap. If branch separation makes consequences feel irrelevant, people can do terrible things without feeling accountable.

But if branch separation is used to deny meaning, then any act of help becomes irrational too. The narrator stands between these extremes, trying to treat alternate people as worthy of effort even when the effort cannot circle back to reward him.

Isolation, identity, and carrying the burden alone

The technician’s voice is calm, practical, and observant, but beneath it sits a deep loneliness shaped by the rules of this universe. Communication between realities stops after return, which means every journey is a severing.

Travelers cannot bring back confirmation, relationships cannot continue across branches, and achievements cannot be validated in the originating world. That structure produces a special kind of isolation: even when you do something meaningful, you must live with it privately.

The narrator embodies this most strongly. He has memories of a doomed world, the authority he held there, and the desperate choice to jump realities with warnings.

After arriving, he cannot return to fix what he left, cannot reconnect with the people he lost, and cannot fully belong in the new timeline because his very existence is a secret. He becomes “a technician,” a role that hides his former identity and forces him into repetition.

The job gives him structure, but it also turns him into a witness of other people’s hopes and disasters, reminding him daily of what he cannot change. Even the encounters where clients meet their younger selves highlight identity as fractured: the self is not a single continuous person but a set of diverging versions, each carrying different regrets and outcomes.

The narrator’s final choice to use his free trip is shaped by this isolation. When catastrophe approaches again, he does not chase heroism; he seeks peace in another world, accepting that he may remain the only constant while everything else collapses or resets around him.

The theme is not simply loneliness, but the psychological weight of being the one who remembers, the one who knows what is coming, and the one who has already tried and failed. In that context, his desire for rest becomes a form of self-preservation, not surrender.