Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead Summary, Characters and Themes

“Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead” is a play written by Tom Stoppard, first performed in 1966.

The play is a comedic, absurdist reimagining of Shakespeare’s “Hamlet,” focusing on the characters Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, two minor characters from Shakespeare’s original play. In “Hamlet,” Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are childhood friends of the prince who are enlisted by King Claudius to spy on Hamlet. However, their roles are relatively minor, and they meet tragic ends offstage.

Summary

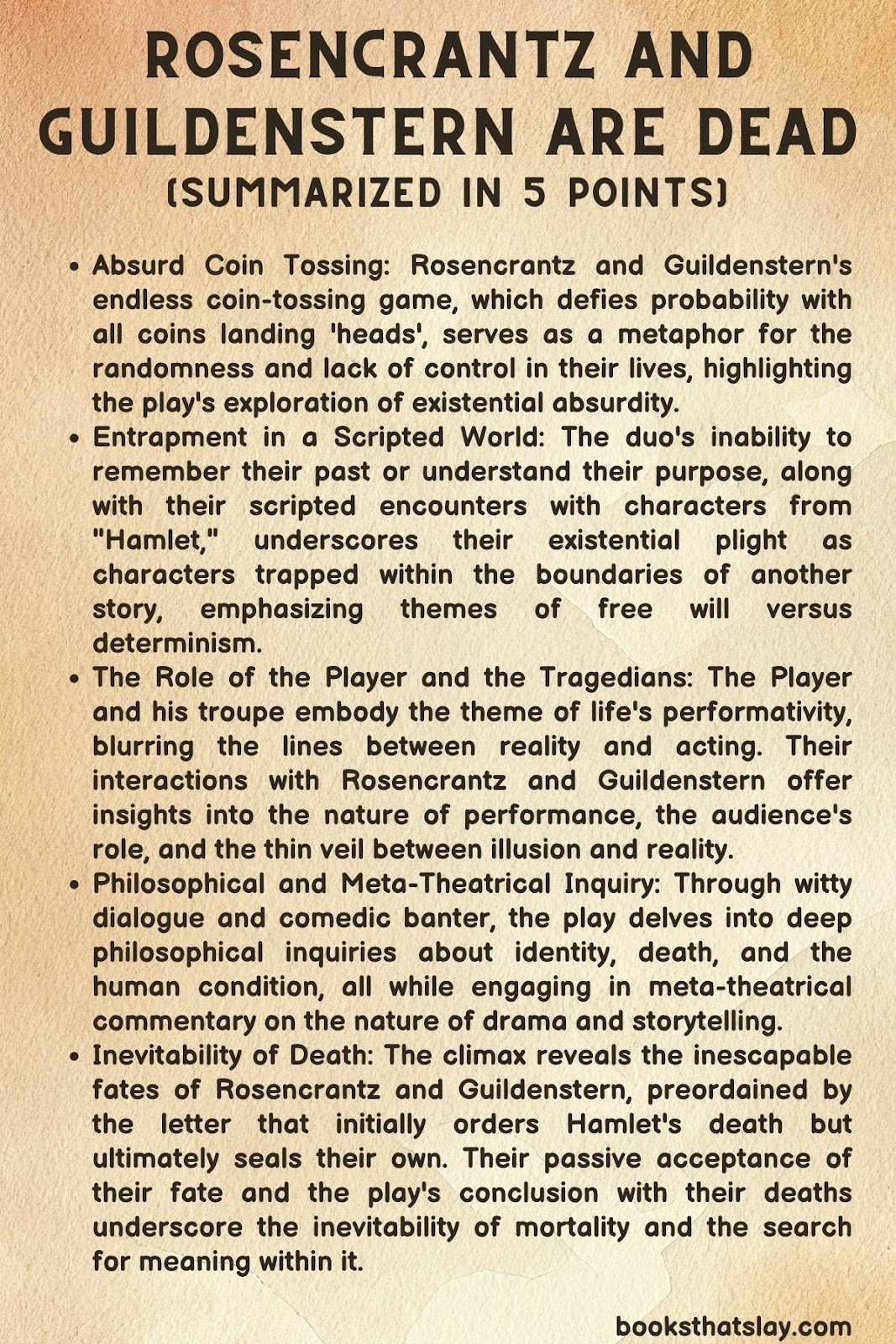

In an Elizabethan-costumed spectacle on a stark stage, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern engage in an endless coin-tossing game, with all coins improbably landing ‘heads.’ While Rosencrantz remains unfazed, Guildenstern’s disturbance grows, urging Rosencrantz to ponder the significance of their bizarre luck.

They struggle to recall anything before this moment, save for a vague memory of a royal summons. The arrival of the Tragedians, led by the Player, disrupts their musings.

The Player attempts to sell them a performance, promising lewd entertainment in line with the crowd’s basest desires for “blood, love, and rhetoric”—primarily blood. After Guildenstern wins two bets against the Player, the latter agrees to perform a play as payment.

The discovery of a ‘tails’ coin by Rosencrantz shifts the scene to Elsinore Castle.

Hamlet and Ophelia make a brief, silent appearance, followed by Claudius and Gertrude, who reveal that they summoned Rosencrantz and Guildenstern to diagnose the cause of Hamlet’s odd behavior. Committed to the task, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern then express their frustration with their incomprehensible situation.

The appearance of Hamlet leads them to rehearse their roles, albeit clumsily. Hamlet’s entrance, teasing Polonius and failing to distinguish between his two friends, closes the act.

Act Two resumes with Rosencrantz and Guildenstern’s futile conversation with Hamlet, who claims his madness depends on the wind’s direction. Guildenstern tries to remain hopeful, despite Rosencrantz’s complaints about their lack of progress.

The Tragedians return, booked by Hamlet, and display hostility towards Rosencrantz and Guildenstern for previously abandoning their performance.

The Player emphasizes the existential reliance of actors on their audience’s gaze and advises them to “act natural” in their dealings with Hamlet.

The rehearsal of the Tragedians’ play, mirroring the plot of Hamlet and predicting Rosencrantz’s and Guildenstern’s deaths, unfolds without their comprehension. Interruptions by the royal family and Polonius occur, with the Player denouncing the play as “a slaughterhouse.”

Guildenstern debates the authenticity of staged deaths, arguing for a more mundane end.

Act Three opens on a ship to England with Rosencrantz, Guildenstern, and Hamlet. Discovering Claudius’s order for Hamlet’s execution in a letter, they contemplate intervention but decide against it.

Their inaction leads to Hamlet replacing the letter with one that orders their deaths instead. Pirates attack, leading to Hamlet’s disappearance and further distress for Rosencrantz and Guildenstern.

Upon realizing their fates, Guildenstern’s attack on the Player, who feigns death convincingly, reveals the illusion of death on stage. The Tragedians celebrate this mock death with a jubilant display.

As the play concludes, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern face their inevitable demise with resignation. Their disappearance precedes the final scene from Hamlet, where an ambassador reports their deaths. The play ends with Horatio’s vow to recount the tragic tale, as the lights dim on the aftermath of Shakespeare’s tragedy.

Characters

Rosencrantz

Rosencrantz, often indistinguishable from Guildenstern to others within the play, embodies a more carefree and less philosophical demeanor. His lack of concern over the coin-tossing sequence’s improbable outcomes showcases his inability, or perhaps refusal, to ponder deeply on the nature of reality and fate.

Rosencrantz’s character navigates through the events with a sense of naivety and a greater willingness to accept the circumstances at face value, without the existential questioning that plagues Guildenstern.

This approach, however, does not spare him from the play’s tragic conclusion, suggesting a commentary on the inevitability of fate regardless of one’s awareness or understanding of it.

Guildenstern

Guildenstern is the more contemplative and philosophical of the duo, deeply troubled by the absurdities and improbabilities they encounter, such as the never-ending string of ‘heads’ in their coin-tossing game.

His tendency to question and seek deeper meanings reflects a struggle to find purpose and order in the chaos that surrounds them. Guildenstern’s existential inquiries, however, often lead him to confusion and frustration, highlighting the play’s exploration of human limitations in comprehending the larger forces at play in life.

His efforts to make sense of their situation and to act meaningfully within it ultimately prove futile, underlining the existentialist themes of absurdity in humans.

The Player

The Player is a complex character who serves as the leader of the Tragedians and represents the theme of performance and illusion within the play.

He is both insightful and manipulative, capable of profound observations about human nature and the essence of theatre. The Player blurs the lines between reality and performance, suggesting that all human actions are forms of acting and that truth is subjective and constructed.

His survival after Guildenstern’s attempt to kill him underscores the play’s meditation on the nature of death and the distinction (or lack thereof) between actuality and artifice.

The Player’s character challenges the audience to question what is real and what is performed, both within the play and in life itself.

Hamlet

Although not the focus of this play, Hamlet’s character influences the narrative significantly. His madness, real or feigned, acts as a catalyst for Rosencrantz and Guildenstern’s mission and ultimately their downfall.

Hamlet’s interactions with the duo oscillate between genuine affection and manipulative deception, reflecting his complex relationship with reality and performance in his own story.

Hamlet’s actions, particularly his alteration of the letter that leads to Rosencrantz and Guildenstern’s doom, demonstrate his agency and cunning, contrasting with the helplessness and confusion of the titular characters.

Hamlet’s presence in the play serves to further emphasize the themes of uncertainty, the fluidity of identity, and the inevitability of fate.

Themes

1. The Absurdity of Existence

The play delves deeply into the existential theme of life’s inherent absurdity, drawing heavily from the existentialist philosophy that suggests life lacks inherent meaning beyond what individuals ascribe to it.

Through the protagonists’ endless coin-tossing and their inability to remember anything before their summons to Elsinore, the play portrays a world where logic and predictability are subverted, highlighting the randomness and lack of control that characterizes human existence.

Their constant questioning and failure to find satisfactory answers to their situation reflect the human quest for meaning in an indifferent universe.

This theme is further accentuated by their roles as minor characters from “Hamlet,” whose lives are dictated by the actions and decisions of others, emphasizing the existential notion that individuals are often at the mercy of forces beyond their comprehension or control.

2. The Nature of Reality and Illusion

The play intricately explores the blurred lines between reality and illusion, especially through the lens of theatricality.

The presence of the Tragedians, who perform plays within the play, serves as a constant reminder of the thin veil between performance and reality. The Player’s assertion that their performance offers the same value as real life, arguing that audience belief in the illusion is all that matters, challenges the characters and the audience to reconsider what they perceive as real.

This theme is epitomized in the climactic moment when Guildenstern stabs the Player, only to find the death was feigned, underscoring the idea that even experiences perceived as most real—such as death—can be simulated, questioning the authenticity of any experience or emotion.

3. The Inevitability of Death

Central to the narrative is the exploration of death’s inevitability and its impact on human consciousness.

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern’s gradual realization of their impending deaths mirrors the universal human journey towards acknowledging mortality.

Their various encounters with the concept of death—through the philosophical musings on the nature of death, the play’s rehearsals that foreshadow their own demise, and ultimately their acceptance of their fate—serve to illustrate the play’s meditation on the inescapable end that awaits all.

This theme is poignantly captured in Guildenstern’s reflections on death as “a man failing to reappear,” a stark, unromanticized view that strips death of its dramatic trappings and presents it as a fundamental, albeit mysterious, cessation of life.

Through this lens, the play invites the audience to confront their own mortality and the meaning they find in the face of it.

Final Thoughts

“Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead” masterfully intertwines humor with profound existential inquiry, presenting its audience with a tragicomedy that reflects on the absurdities of life through the lens of two minor Shakespearean characters.

Tom Stoppard’s play is a brilliant exploration of existential philosophy, the nature of performance, and the human condition, all while paying homage to Shakespeare’s “Hamlet.” Its clever dialogue, engaging plot twists, and deep thematic content make it a compelling read (or view) that resonates with audiences by challenging perceptions of reality, identity, and the inevitability of death.

The play’s ability to balance existential dread with comedic relief, and its meta-theatrical approach to storytelling, not only entertain but also provoke thoughtful reflection on the parts we all play in the grand scheme of life.