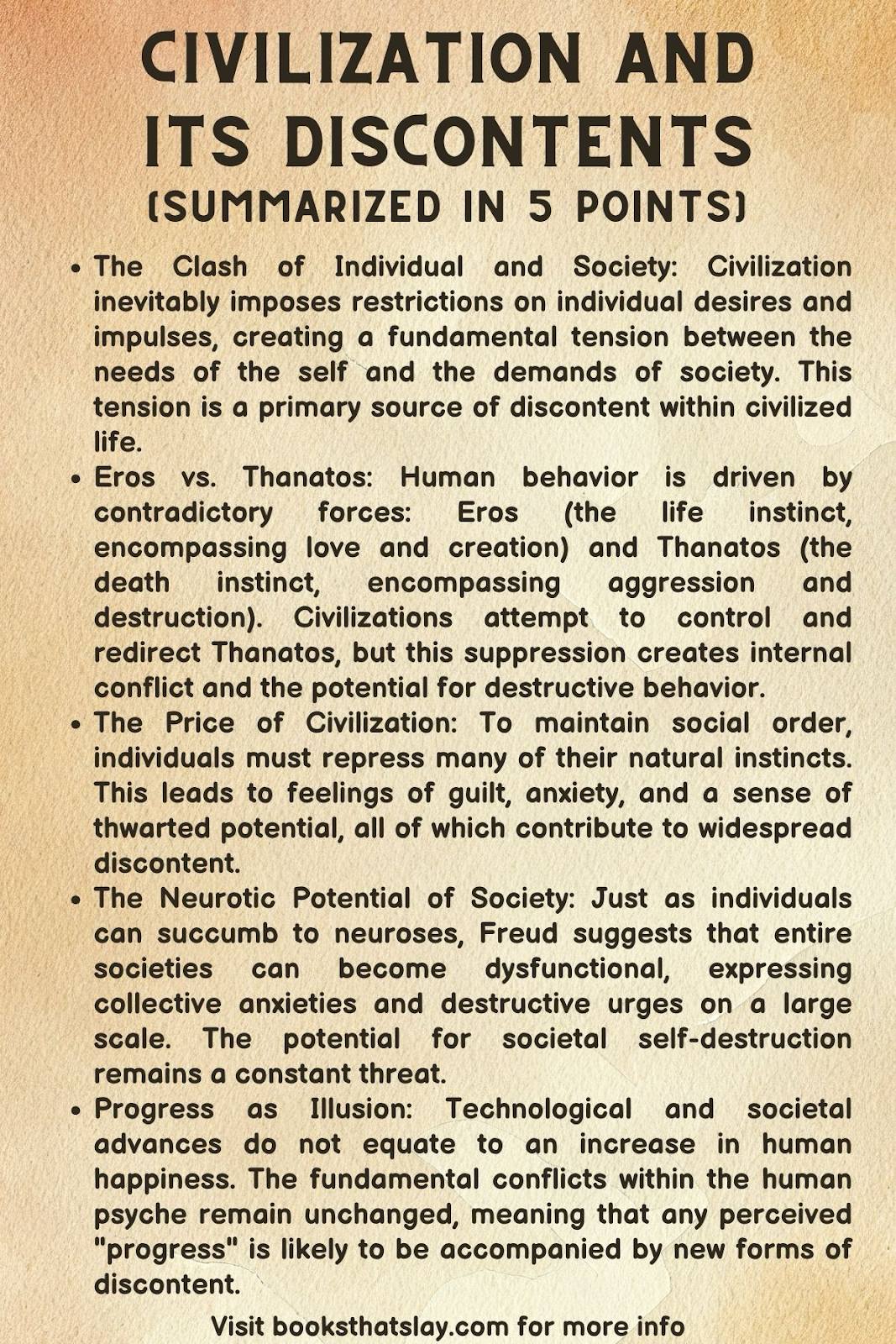

Civilization and Its Discontents Summary and Themes

Sigmund Freud’s Civilization and Its Discontents grapples with the fundamental conflict between the individual and the constraints of society.

The book dives into the psychological underpinnings of social structures and the internal tensions driving human behavior.

Summary

Freud begins by expressing his confusion about the nature of “religious feeling,” a phenomenon he does not personally experience but recognizes as a powerful force within society.

He views religion as an expression of a larger desire for selfless love, wondering if this ideal is the primary force holding civilization together.

However, he concludes that love alone cannot explain the complexities of social bonds.

To better understand human social behavior, Freud examines the origins of familial bonds. He posits that sexual love (eros) between parents and children creates complex relationships.

These attachments are characterized by a paradoxical combination of a deep love and a repressed, often unconscious, desire for destruction (thanatos). This push-and-pull dynamic creates an “interrupted” sexuality within the family, shaping individual yearnings.

Freud then extends his theory to society at large. He argues that the same forces present in families – love and aggression – also exist within larger communities and the concept of civilization as a whole.

Individual desires for freedom and personal gratification clash with the societal need for order and collective well-being. Civilizations are thus formed out of an uneasy compromise, a constant tension between the individual and the group.

He critiques other theories of social cohesion, such as the Christian Golden Rule, as overly focused on communal love while ignoring the innate impulses of individual actors. Freud’s model, in contrast, emphasizes the competing needs of the person and the collective. He recognizes both the longing for freedom and the desire for protection within civilization.

Against the backdrop of 1930s Europe, where communism and fascism were challenging existing social orders, Freud contemplates the very health of civilization. He questions whether societies can become neurotic, overwhelmed by the destructive impulses inherent within the human psyche.

Themes and Takeaways

1. The Individual vs. Society

Freud delves into the profound psychological cost of living within a civilized society. Society, by its very nature, demands adherence to rules, shared values, and often a degree of personal sacrifice.

While recognizing the benefits of community and structure, Freud emphasizes that these come at the expense of the individual’s instinctual freedom. This means the constant suppression of desires for immediate pleasure, unbridled sexual expression, and often the redirection of aggression.

This suppression results in an inescapable sense of tension and, for some, a pervasive feeling of discontent. The very act of civilization requires a form of self-denial, and this fundamental conflict between the untamed psyche and societal expectations lies at the heart of human unhappiness, according to Freud.

2. Eros and Thanatos

Freud’s concept of Eros and Thanatos introduces an even more unsettling layer to this societal conflict. Eros, the life instinct, fuels our desire for love, procreation, and the building of bonds.

Countering this, Thanatos, the death instinct, encompasses aggression, destruction, and a paradoxical urge towards self-annihilation.

These two forces are not in harmony but rather in a constant state of battle within the human psyche. Civilization, as a means of ensuring social order, attempts to redirect and sublimate Thanatos.

But this repression, Freud argues, does not eliminate our destructive impulses. Rather, it forces them underground, where they fuel constant internal struggles, feelings of guilt, and the potential to explode outward in socially destructive ways.

The very stability of civilization is therefore underpinned by a barely concealed volatility, which Freud sees as a constant threat.

3. The Neurotic Society

Building upon this understanding of the psychological price of civilization, Freud raises a chilling possibility: if individuals can succumb to neuroses born from repression and conflicting drives, can societies themselves become ‘neurotic’?

The rise of extremist ideologies like communism and fascism in his own era led him to fear that civilizations may fall into a collective dysfunction, driven by either the unchecked unleashing of Thanatos in violent form, or through a rigid over-control that pushes destructive impulses inwards, resulting in widespread societal misery.

Freud’s question haunts us to this day – can societies learn to transcend their destructive urges, or are they trapped in a cycle of re-enacting their darkest impulses on an ever-grander, more dangerous scale?

4. The Role of Guilt and the Superego

Freud places great emphasis on the psychological mechanisms that enforce social control even in the absence of direct external threats.

The superego, the part of our psyche that internalizes societal values and expectations, becomes a constant source of self-surveillance and guilt.

Civilization demands we forgo certain pleasures or curb destructive impulses, and the superego stands guard, ready to punish us with guilt and shame for any transgressions, real or perceived.

According to Freud, this internalized guilt is a major contributor to the discontent of civilized life.

Even when we act in accordance with societal rules, we may feel a nagging unease stemming from the superego’s impossible demands for perfection and the fear of violating its often unconscious moral code.

5. The Illusion of Progress

Freud expresses a deeply pessimistic view of human progress, especially in relation to happiness.

He posits that while technological advancement and societal evolution may bring about material comforts or greater organization, they do not fundamentally change human nature. We carry with us the same primordial desires and destructive impulses that marked earlier stages of civilization.

Therefore, Freud argues that any notion of progress leading towards a utopian state of collective contentment is fundamentally flawed.

Rather, civilization is an ongoing project of managing our destructive tendencies, and any perceived progress in one area might simply create new forms of dissatisfaction in another.