The Eumenides Summary, Characters and Themes

The “Eumenides” is a famous Greek tragedy and the final part of Aeschylus’s trilogy, the “Oresteia.”

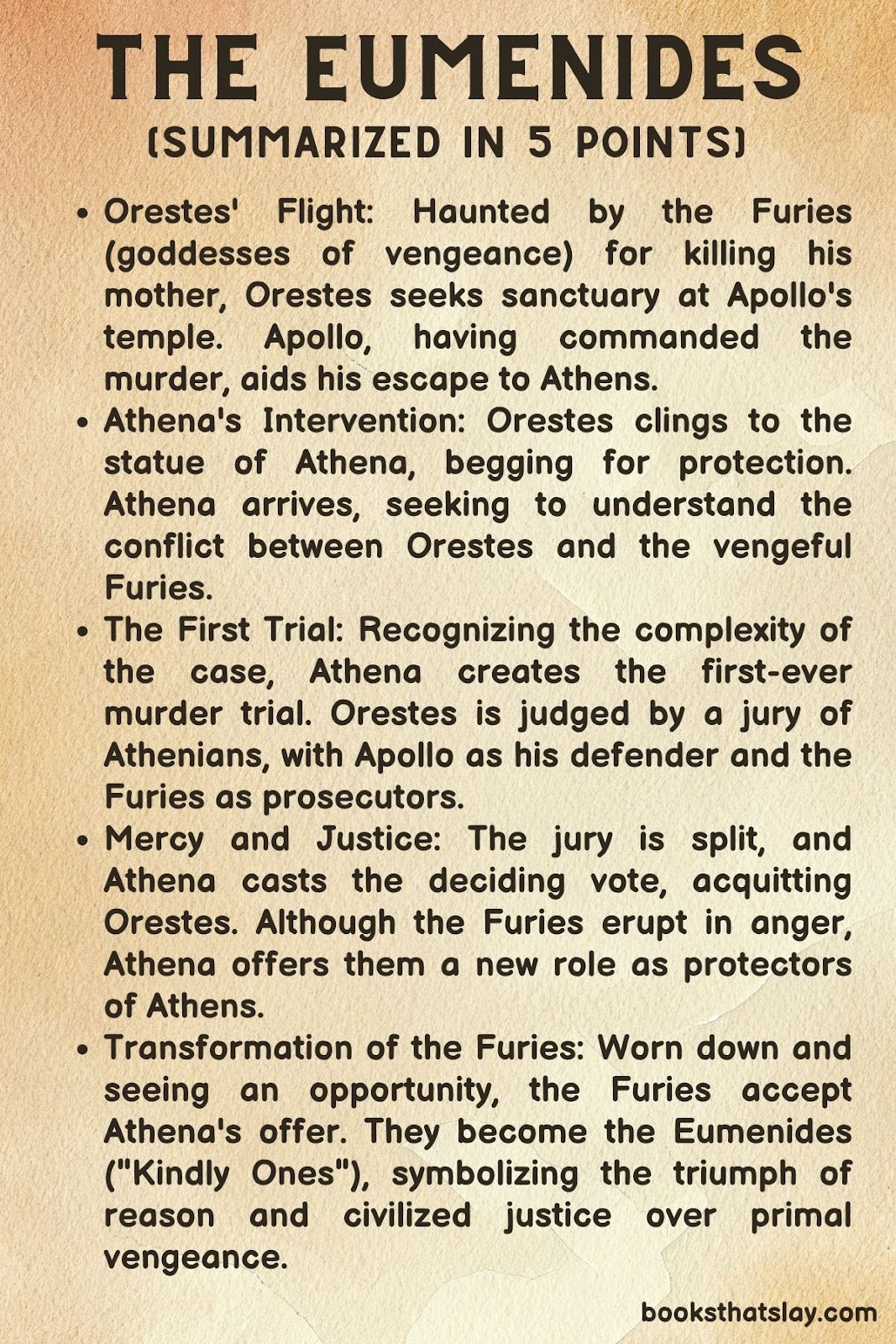

The play revolves around Orestes, who is haunted by the vengeful Furies (also called the Eumenides) after murdering his mother, Clytemnestra. Seeking justice, he goes to trial in Athens with the goddess Athena presiding. The play deals with themes of bloodguilt, societal order, and the evolution of justice from primitive revenge to a civilized court system.

Summary

The play opens inside Apollo’s temple. His priestess, Pythia, prepares for morning prayers but is interrupted by the arrival of a terrified and bloodstained Orestes. He has murdered his mother, Clytemnestra, to avenge the death of his father, Agamemnon, whom she killed.

Relentlessly pursuing Orestes are the Furies, ancient goddesses of vengeance, driven to punish him for his matricide.

Pythia flees in horror, but Apollo appears, revealing that he commanded Orestes’ actions. To ensure Orestes’ escape, he lulls the Furies to sleep while his brother Hermes guides Orestes to Athens for sanctuary.

The ghost of Clytemnestra then rises, scornfully goading the Furies for failing to punish her son. Awakening, the Furies rage at this betrayal by the younger Olympians.

Apollo emerges, clashing with them in a heated debate over their archaic blood vengeance versus his ideals of justice. He vows to protect Orestes as the Furies swear relentless pursuit.

The scene shifts to Athens.

Orestes clings to a statue of Athena, desperately praying for her protection as the Furies close in. Athena descends, demanding an explanation for this disruption to her city. Both Orestes and the Furies plead their case, agreeing that Athena shall be the judge of Orestes’ fate.

Athena, bound by her duty to justice, finds the case too complex for her alone to decide. Inspired, she establishes the first-ever murder trial with a jury of Athenian citizens. The Furies argue the sacredness of the bond between mother and child, that Orestes’ crime cannot go unpunished.

Apollo counters, claiming that the father holds greater importance within a family, and was himself acting on divine orders.

The jury’s vote is split. Athena, possessing the tie-breaking vote, chooses to side with Apollo, declaring Orestes innocent and setting him free.

The Furies erupt in fury.

They believe Athena has stripped them of their purpose, their ancient power. Athena, ever wise, sees an opportunity. She offers them a new role: as honored protectors of Athens, the Eumenides (“Kindly Ones”).

Should they bring peace and prosperity to the city, they will receive reverence and respect.

After hesitation, the Furies, worn down and seeing potential in this new role, accept.

The play ends on a note of transformation.

The raw, bloody cycle of vengeance gives way to a system of civilized justice championed by Athena. The ancient, terrifying Furies are reborn as the Eumenides, a testament to the power of reason and the evolution of society.

Characters

Orestes

Orestes is the core of the conflict within the play, embodying a clash between old and new ways of justice. He’s both a haunted, desperate figure and an instrument of divine will.

His matricide, while horrific, was an act commanded by Apollo to avenge Agamemnon. Orestes carries immense guilt, fear, and doubt about the true path of righteousness.

He is ultimately a pawn in the struggle between the archaic law of the Furies and the evolving justice represented by Athena and Apollo.

The Furies

The Furies aren’t individual characters but a terrifying chorus. They represent the ancient law of blood for blood, where crimes against kin trigger relentless retribution.

They are visually monstrous, reflecting their raw, primal nature. Their language is vengeful and violent. The Furies’ evolution into the Eumenides is the greatest character arc of the play.

It demonstrates the possibility of transformation, that even the most ingrained powers of punishment can adapt to a world where forgiveness and order have a place.

Athena

The goddess of wisdom embodies the play’s central theme: the establishment of civilized justice to replace unchecked vengeance. She is reasoned, balanced, and far-sighted.

Athena’s creation of the first jury reflects her belief in process and communal participation in determining guilt or innocence.

Through her skillful negotiation with the Furies, Athena shows her wisdom is not just about ruling but about fostering peace and societal harmony.

Apollo

The god of light and prophecy is Orestes’s fierce protector. He represents a younger generation of Olympians who believe their law should supersede that of older deities like the Furies.

Apollo can be seen as arrogant, dismissing the Furies’ power, yet he also believes in a form of justice that takes mitigating circumstances into account.

While he represents a change from the Furies’ brutality, his argument that men are superior to women shows that even within the new order, traces of outdated systems persist.

Themes

The Evolution of Justice

The central conflict of “Eumenides” stems from a clash between two contrasting systems of justice. The Furies represent the archaic concept of blood vengeance, where acts of violence are met with an equal and opposite reaction, perpetuating a never-ending cycle.

This system is based on familial ties and retribution. Apollo and Athena, however, embody the nascent Athenian ideals of rational judgment and mercy.

The establishment of Athena’s council marks a watershed moment, signifying a shift from personal vengeance towards a more structured and impartial form of justice.

While not without its flaws (the jury’s deadlock, Athena’s own bias), this trial demonstrates the potential for reason and measured debate to resolve even the most complex and morally fraught cases.

The Role of Divine Intervention

Divine forces play a pivotal role in shaping the events of “Eumenides”. Apollo actively orchestrates Orestes’ flight and defense, claiming that he commanded Orestes’ matricide – a bold assertion of his authority over the older deities.

Athena emerges as the ultimate arbiter, dispensing wisdom and brokering peace. However, the conflict between the Furies and the Olympians highlights the messy and often contradictory nature of divine interactions.

The play leaves us questioning the motivations of the gods: are they driven by justice and wisdom, or do personal agendas and ancient rivalries overshadow their judgment?

Civilization vs. The Primal

Through the Furies, Aeschylus presents a chilling portrayal of primal forces – ancient, instinctive, and driven by an insatiable thirst for blood.

Their grotesque appearance, their relentless pursuit of Orestes, and their thirst for vengeance embody the raw power of unbridled emotion.

Athena and Athens become symbols of civilization, reason, and the potential for societal order.

Yet, the Furies’ eventual transformation into the benevolent Eumenides suggests that even the most primal forces can be harnessed and integrated into a civilized structure.

This isn’t about outright suppression, but rather the channeling of raw energy into constructive purposes.

The play suggests that true civilization lies not in denying our primal nature, but in finding ways to reconcile it with reason and the pursuit of a greater good.