Happy Place Summary, Characters and Themes

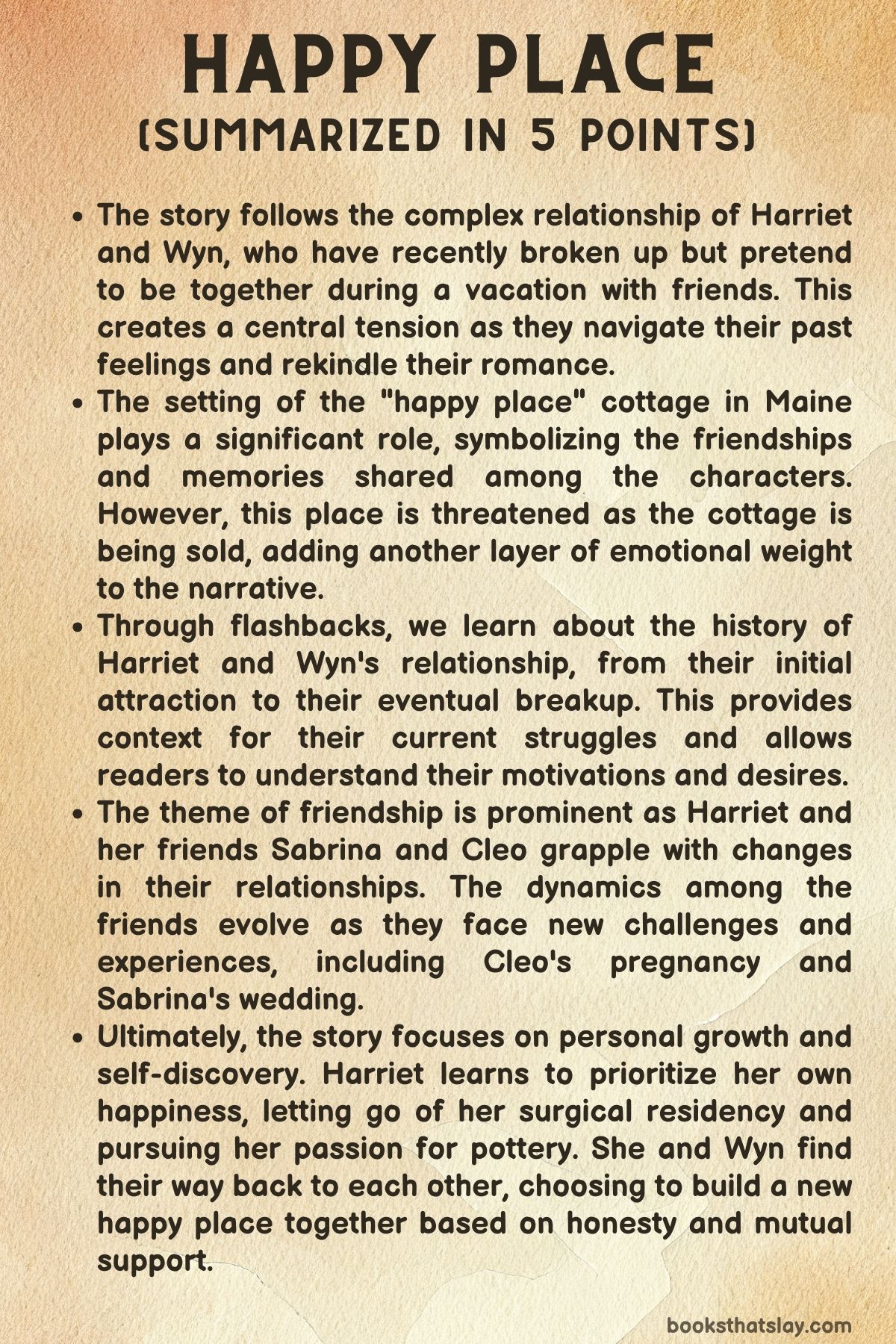

Happy Place by Emily Henry is a contemporary romance novel exploring the complexities of relationships and the search for one’s own happiness.

The story follows a couple, Harriet and Wyn, who have recently broken up but pretend to still be together during a vacation with their friends. As they navigate their past and present feelings, the book delves into themes of love, loss, friendship, and self-discovery. With Emily Henry’s signature wit and charm, Happy Place is a heartfelt and entertaining read about finding joy and contentment in unexpected places.

Summary

Harriet Kilpatrick, a worn-out surgical resident, embarks on her annual summer escape to a cherished cottage in Maine, a place fondly dubbed their “happy place.”

She anticipates reuniting with her close-knit group of friends: Sabrina, Parth, Cleo, and Kimmy. Unbeknownst to them, Harriet carries a secret burden—her recent separation from her fiancé of eight years, Wyn Connor.

Arriving at the idyllic retreat, Harriet is met with an unexpected twist: Wyn is also present, determined to maintain the illusion of their love for the sake of their oblivious friends. Resentful yet understanding, Harriet agrees to play along, masking their true feelings behind a façade of affection.

As the group indulges in their customary summer activities—savoring Lobster Fest, embarking on boat trips, dancing under the stars, and revisiting cherished haunts—Wyn’s reservations about their breakup become increasingly apparent.

Yet, Harriet hesitates to express her own lingering feelings of loss and confusion.

Through a series of flashbacks, readers are transported back to the genesis of Harriet’s friendships in college and the blossoming of her passionate love story with Wyn.

Their relationship weathered the trials of distance, career demands, and personal tragedies, culminating in a painful split after Wyn’s father’s passing.

In the present, as Sabrina and Parth’s wedding approaches, Harriet and Wyn find themselves navigating a delicate dance of communication and self-reflection.

They confront the underlying issues that led to their separation: Wyn’s struggles with grief and self-doubt, and Harriet’s exhaustion and reluctance to address their future together.

A turning point emerges when Wyn encourages Harriet to pursue her true passion for pottery, recognizing her unhappiness with her chosen career path.

Emboldened by his support, Harriet confides in her friends about the breakup, triggering a cathartic confrontation that exposes long-simmering tensions within the group.

In the aftermath of the emotional storm, a newfound understanding dawns upon the friends, solidifying their bond as they navigate the complexities of life and love.

Harriet makes the life-changing decision to abandon her surgical residency and pursue her artistic calling, ultimately moving to Montana to reunite with Wyn and forge a new chapter in their shared “happy place.”

Characters

Harriet Kilpatrick

Harriet Kilpatrick, the protagonist of “Happy Place,” is a 30-year-old surgical resident known for her conflict-avoidance and overwork.

Raised in a reserved family, Harriet grew up feeling disconnected, her first real sense of belonging emerging in college when she met her close friends, Sabrina and Cleo. Over time, Harriet’s career ambitions led her to pursue a surgical residency in San Francisco, a path chosen more to please her demanding parents than out of personal desire.

Despite her outward success, Harriet grapples with inner turmoil, exhaustion, and a burgeoning realization that surgery may not be her true calling. Her engagement to Wyn Connor, initially a source of joy, falters under the strain of long-distance separation and her relentless work schedule.

Harriet’s journey throughout the novel is one of self-discovery, as she learns to prioritize her own happiness, ultimately deciding to leave her surgical career to pursue pottery, a newfound passion that allows her creative expression without the weight of others’ expectations.

Her reconciliation with Wyn and decision to move to Montana symbolize her break from past constraints and embrace of a more fulfilling, authentic life.

Wyn Connor

Wyn Connor is Harriet’s ex-fiancé and soulmate, whose breakup with her serves as a central conflict in the novel.

Wyn is characterized by his deep love for his family and his struggle with depression following his father’s death. Originally from Montana, Wyn finds himself out of place and dissatisfied while living in San Francisco with Harriet, exacerbated by his difficulty in securing a job.

His decision to move back to Montana to care for his ailing mother highlights his strong familial bonds and sense of duty. Despite his love for Harriet, Wyn breaks off their engagement, believing that his emotional turmoil and physical distance are hindering her ambitious career.

Throughout their week-long stay at the cottage, Wyn’s lingering feelings for Harriet become evident, and he remains supportive of her evolving self-awareness. Wyn’s encouragement for Harriet to pursue pottery instead of surgery underscores his desire for her to be happy and fulfilled.

Ultimately, Wyn’s character arc culminates in his reunion with Harriet and their joint decision to live a simpler, more authentic life together in Montana.

Sabrina

Sabrina, a lawyer and the daughter of a wealthy family, is one of Harriet’s closest friends and the de facto leader of their friend group.

Her ownership of the cottage in Knott’s Harbor, Maine, establishes the setting for their annual gatherings, which serve as a sanctuary and “happy place” for the friends.

Sabrina’s life appears outwardly perfect, yet she harbors her own insecurities and feelings of neglect within the group. Her impending marriage to Parth and the sale of the cottage add layers of complexity to her character, revealing her struggle to maintain connections and traditions amidst life’s inevitable changes.

Sabrina’s confrontation with Harriet about their faltering friendship demonstrates her deep emotional investment in maintaining their bond. Despite her sometimes forceful personality, Sabrina is ultimately a caring and loyal friend, committed to the happiness and unity of their group.

Her character embodies the challenges of balancing personal aspirations with the preservation of meaningful relationships.

Parth

Parth is Sabrina’s boyfriend and later husband, a law school classmate who becomes an integral part of the friend group. His relationship with Sabrina is stable and supportive, contrasting with the more tumultuous dynamics between Harriet and Wyn.

Parth’s character is less explored in depth compared to others, but he plays a crucial role in the narrative by supporting Sabrina and facilitating the group’s cohesion. His upcoming wedding to Sabrina at the cottage adds a sense of urgency and finality to their last gathering at the “happy place.”

Parth’s presence is a stabilizing force within the group, and his support for Sabrina’s emotional needs highlights his dependable and caring nature.

Cleo

Cleo, one of Harriet’s college friends, is an artsy and free-spirited farm owner.

Her relationship with Kimmy, her girlfriend, and her unconventional lifestyle provide a counterpoint to Harriet’s structured and demanding career. Cleo’s character represents independence and the pursuit of personal passions, having established a farm with Kimmy that reflects their commitment to a non-traditional way of life.

Throughout the novel, Cleo’s pregnancy and her refusal to get matching tattoos highlight her readiness to embrace change and new responsibilities. Cleo’s confrontation with Harriet about their changing friendship dynamics underscores her desire for honesty and deeper connection within their group.

Ultimately, Cleo’s pregnancy becomes a unifying factor, helping to mend the rifts in their friendship and bring the group closer together.

Kimmy

Kimmy is Cleo’s girlfriend, a vibrant and energetic character who brings joy and spontaneity to the group.

As an artist and farmer, Kimmy complements Cleo’s character and shares her commitment to their shared lifestyle. Although her role in the narrative is not as prominent, Kimmy’s presence is significant in representing the diversity of paths the friends have taken since college.

Her relationship with Cleo is depicted as loving and supportive, providing a stable backdrop to the more turbulent relationships in the story.

Kimmy’s interactions with the group contribute to the overall theme of acceptance and the importance of maintaining close friendships despite life’s changes.

Harriet’s Parents

Harriet’s parents are depicted as demanding and traditional, with high expectations for their daughter’s career in surgery. Their influence on Harriet is a significant factor in her initial career choice and her struggle with people-pleasing tendencies.

Throughout the novel, Harriet’s relationship with her parents is strained by her desire to break free from their expectations and pursue a more fulfilling path. Their initial disapproval of her decision to quit her surgical residency and become a potter underscores the tension between familial duty and personal happiness.

However, Harriet’s eventual resolve to follow her passion and their gradual acceptance signify her growth and newfound assertiveness.

Martin

Martin is a residency friend of Harriet’s whose impulsive kiss contributes to the misunderstanding and subsequent breakup between Harriet and Wyn.

His character serves as a catalyst for the events that lead to Harriet’s self-examination and the eventual reconciliation with Wyn. Martin’s actions, although brief in the narrative, have a significant impact on the story, highlighting the fragile nature of trust and communication in relationships.

His presence in the plot underscores the challenges Harriet faces in her professional life and the consequences of unresolved emotions.

Themes

The Complexity of Relationships

In Happy Place, relationships are examined through the layered, sometimes contradictory realities of love, friendship, and family expectations, revealing how they morph under the weight of distance, grief, career pressures, and unspoken insecurities.

Harriet and Wyn’s relationship becomes a mirror reflecting how even profound love can fracture when personal aspirations and emotional needs are neglected, despite the depth of their connection.

Their breakup, while rooted in practical issues like geographical separation and Harriet’s demanding residency, also emerges from a quieter erosion caused by avoidance, fear, and the silent hope that the other will compromise first.

Meanwhile, the friendships within the group serve as another landscape where complexity unfolds, especially as the illusion of a “happy place” is challenged by the realities of adulthood.

Sabrina’s meticulous attempts to preserve traditions and Cleo’s insistence on individuality create friction, showing how even the strongest friendships demand vulnerability, compromise, and periodic recalibration to survive evolving personal goals.

The dynamic between these friends captures the bittersweet nature of growing up together, where love for one another coexists with disappointment and jealousy, as each person’s choices inevitably impact the group’s harmony.

Harriet’s conflict-avoidance habit highlights how maintaining peace often comes at the cost of authenticity, straining her connection with her friends and Wyn.

The novel shows that relationships are neither inherently stable nor doomed to fail but are living, breathing connections requiring honesty, sacrifice, and courage to adapt as people change.

Rather than depicting relationships as clear-cut paths, the story honors their nuance, capturing how love and friendship can both break and heal in the process of becoming truer to oneself.

Self-Discovery and Personal Growth

Harriet’s journey in Happy Place is one of peeling away layers of externally imposed identities to reveal a truer self, emphasizing that self-discovery is often uncomfortable but essential for a meaningful life.

Her surgical residency, chosen to appease her demanding parents and align with societal prestige, becomes an emblem of a life that looks successful on the outside but drains her spirit internally.

The exhaustion, loss of self, and emotional numbness Harriet experiences within her career mirror the broader theme of how individuals lose themselves in the pursuit of expectations that do not align with their inner desires.

This dissonance between the life she is living and the life she wants intensifies in the presence of Wyn, whose gentle nudging encourages her to reflect on her dissatisfaction and long-suppressed artistic inclinations.

Harriet’s discovery of pottery as a passion is not simply a hobby but a reclaiming of her agency, allowing her to choose a path rooted in creativity, peace, and personal fulfillment rather than societal validation.

Similarly, Wyn’s decision to leave San Francisco and return to Montana after his father’s death is an act of aligning with his values, embracing the quiet satisfaction of living authentically over the strain of maintaining appearances in a life that does not suit him.

The theme is amplified through the backdrop of the “happy place” in Maine, which serves as both a nostalgic comfort and a mirror forcing Harriet to acknowledge how far she has drifted from her true self.

By the end of the novel, Harriet’s choice to leave her medical career and pursue pottery in Montana symbolizes her commitment to building a life that honors her needs, revealing that personal growth often requires the courage to disappoint others to live authentically.

The Importance of Honest Communication

In Happy Place, honest communication is the hinge upon which healing, reconciliation, and growth pivot, underscoring how avoidance, silence, and the fear of conflict can quietly erode even the deepest relationships.

Harriet and Wyn’s breakup, although rooted in complex circumstances like long-distance strain and personal grief, is exacerbated by their inability to express their vulnerabilities and frustrations.

Harriet’s tendency to avoid conflict and maintain the appearance of composure leads her to suppress her exhaustion and unhappiness, while Wyn’s struggle with grief and self-doubt silences him, creating a chasm where misunderstandings fester.

Their week in Maine, pretending to still be together, becomes a forced opportunity to confront the words left unsaid, turning every touch, memory, and argument into a chance to articulate the truths they have both been avoiding.

This theme extends into the dynamics of the friend group, where unspoken disappointments and expectations simmer beneath the surface, occasionally erupting in moments of confrontation, like Sabrina’s outburst over Harriet’s emotional distance or Cleo’s frustration with Sabrina’s need for control.

These conflicts, though painful, become catalysts for deeper honesty and connection, allowing each friend to understand and accept the others’ choices and boundaries.

The novel demonstrates that while conflict is uncomfortable, it is often necessary to address the hidden fractures that threaten relationships.

The moments of catharsis in the narrative, such as Harriet finally confessing her unhappiness in surgery and acknowledging her desire to pursue pottery, illustrate that honesty is not only about resolving immediate issues but about creating space for true intimacy and growth.

Happy Place reinforces that while maintaining harmony may feel like love, true connection demands the bravery to speak one’s truth, even when it risks discomfort, because only then can relationships thrive in authenticity.

The Search for Belonging and Home

In Happy Place, the search for belonging and the idea of “home” operate as an undercurrent driving Harriet’s actions and emotional struggles, shaping her longing for stability in a life that often feels transient and unmoored.

Harriet’s childhood in a cold, emotionally distant household leaves her craving connection, a need partially fulfilled when she meets Sabrina and Cleo in college and experiences the warmth of chosen family for the first time.

The annual trip to the Maine cottage, their designated “happy place,” becomes a physical representation of this belonging, a temporary escape where Harriet feels seen, valued, and grounded in the love of her friends.

However, as the story progresses, the illusion of permanence in this setting begins to crack, forcing Harriet to confront the reality that places alone do not sustain belonging; it is the honesty and authenticity within relationships that do.

Wyn’s role in Harriet’s life further complicates her understanding of home, as he embodies a sense of safety and deep emotional connection, even when circumstances push them apart. His return to Montana after his father’s death and his yearning for the simplicity of his hometown stand in contrast to Harriet’s restless striving in San Francisco, highlighting that home is not a single place but the feeling of alignment between one’s environment and inner self.

By the end of the novel, Harriet’s decision to leave her surgical residency and move to Montana to be with Wyn is not merely a romantic gesture but an acknowledgment that belonging is rooted in living authentically, choosing spaces and people who foster peace rather than pressure. The theme emphasizes that the quest for a “happy place” is ultimately about finding or creating environments where one feels free to be fully themselves, and where love and acceptance replace performance and fear.

Letting Go and Embracing Change

Letting go of expectations, old identities, and fear of the unknown forms another central theme in Happy Place, illustrating how personal freedom often requires surrendering what once felt safe or necessary.

Harriet’s life is tightly controlled by expectations, whether it is her parents’ insistence on a prestigious medical career, her own fear of disappointing those she loves, or the stability she seeks through meticulous planning and avoidance of conflict.

This desire for control initially keeps her in a profession that drains her spirit, in a long-distance engagement strained by silence, and in friendships where deeper issues are buried beneath politeness.

The Maine cottage itself, with its traditions and nostalgia, represents a reluctance to let go of the past, as the group clings to their ritual even when underlying tensions threaten their closeness.

However, the impending sale of the cottage and the approaching wedding force each character to confront change, acknowledging that clinging to past versions of themselves and each other prevents growth.

Wyn’s willingness to step away from San Francisco, despite his love for Harriet, to care for his mother and rediscover himself in Montana embodies the courage required to let go, as does Harriet’s final decision to leave her residency and embrace pottery despite the risks and the disapproval it initially brings.

These choices are not easy, as they involve grief for what could have been and fear of stepping into uncertain futures, but they ultimately lead to lives that are more aligned with their authentic desires.

The theme underscores that change, while unsettling, is a vital part of pursuing happiness and fulfillment, requiring individuals to trust that what they gain in self-alignment and peace outweighs the comfort of familiarity.

In Happy Place, embracing change becomes a radical act of self-love, revealing that true happiness often lies on the other side of letting go.