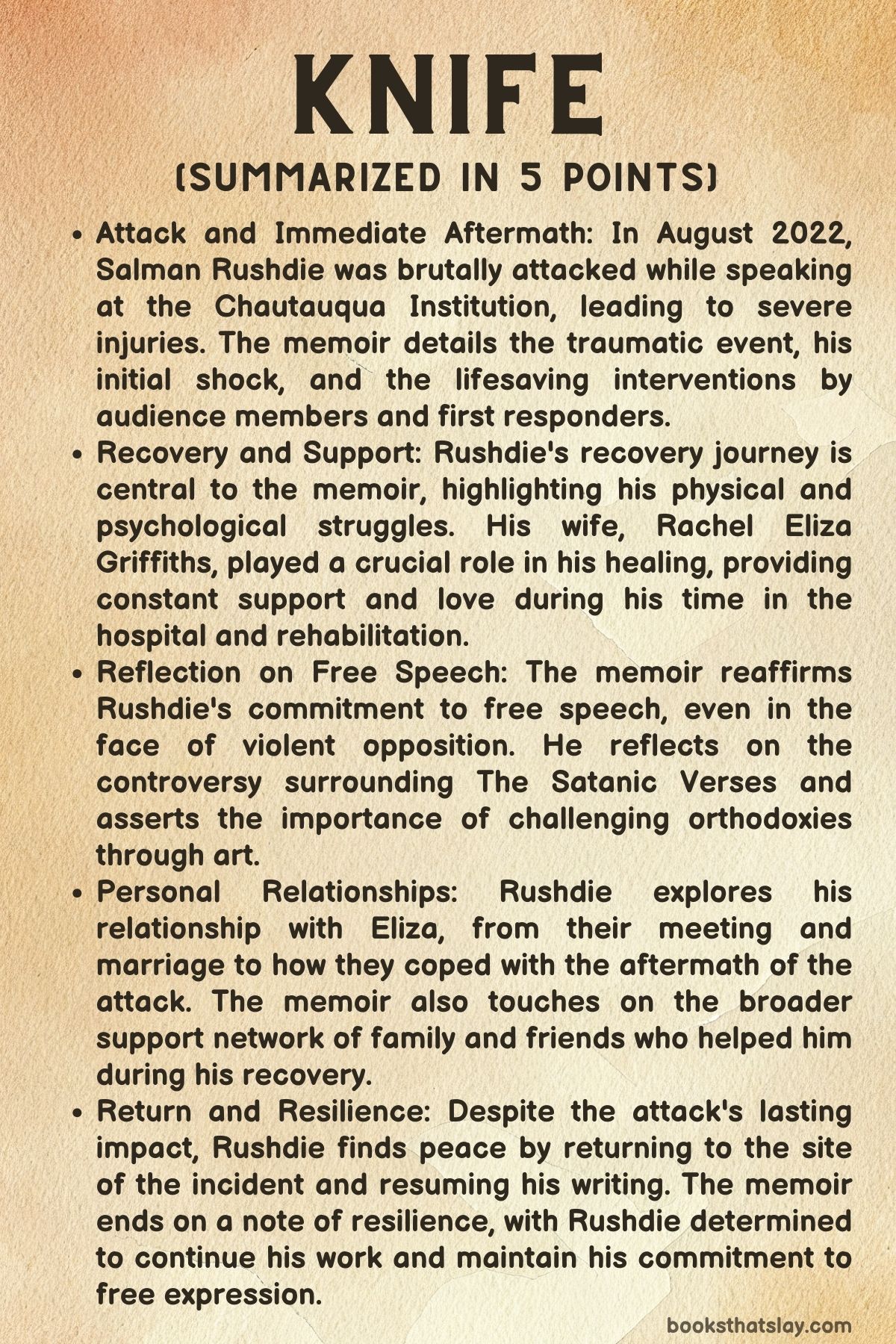

Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder Summary, Analysis and Themes

“Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder,” Salman Rushdie’s memoir published in 2024, is a profound reflection on survival, resilience, and the enduring power of free speech. The book delves into the harrowing 2022 attack that nearly claimed his life, detailing his journey of recovery—both physical and psychological.

Through this memoir, Rushdie revisits the trauma, honors those who stood by him, and reaffirms his unwavering belief in the freedom to challenge oppressive ideologies. It is also a tribute to the love and support of his wife, Rachel Eliza Griffiths, who played a central role in his healing process.

Summary

In 2022, Salman Rushdie was invited to speak at the Chautauqua Institution, a serene summer retreat in New York. Just before his scheduled appearance, he had a disturbing dream about being stabbed, which left him uneasy. Nonetheless, he decided to fulfill his commitment to speak about the City of Asylum Pittsburgh Project—a sanctuary for writers in danger.

On August 12, as he took the stage alongside Henry Reese, a 24-year-old man named Hadi Matar—referred to in the memoir simply as “the A.”—stormed the stage and violently attacked Rushdie with a knife.

In shock, Rushdie found himself unable to defend himself effectively. Audience members quickly intervened, subduing the assailant and administering first aid to Rushdie until emergency responders arrived. Overwhelmed by the thought that he might never see his loved ones again, Rushdie was airlifted to a trauma center in Pennsylvania, where he underwent emergency surgery to treat his severe injuries.

Five years earlier, Rushdie had met Rachel Eliza Griffiths, a fellow writer, at the PEN America World Voices Festival.

Their connection was immediate, and they soon began a relationship, carefully shielding it from public scrutiny due to Eliza’s discomfort with the spotlight. They married in September 2021 and enjoyed a brief, blissful period before their lives were irrevocably changed by the attack.

After learning of the incident, Eliza rushed to Rushdie’s side at the hospital, where he was intubated and battling immense pain, exacerbated by hallucinations from powerful painkillers.

Despite his dire situation, the unwavering presence of Eliza and the support from family and friends provided him with much-needed solace. Global outpourings of support, though occasionally perplexing to the atheist Rushdie, lifted his spirits.

As he began documenting his experience through recordings, Rushdie found the loss of vision in his right eye particularly devastating. However, his determination to recover fueled his gradual progress, and after 18 days, he was transferred to Rusk Rehabilitation in New York City.

In New York, Rushdie felt confined in the rehabilitation center, despite the comfort of visits from his son Milan and Eliza. During his restless nights, he contemplated the symbolic nature of the knife and its parallel to language—a tool that could both wound and heal.

Encouraged by his agent, Andrew Wylie, to write about the attack, Rushdie initially hesitated but eventually embraced the idea as a form of resistance. Reflecting on his life, he revisited the controversy surrounding The Satanic Verses and reaffirmed his belief in the importance of free expression.

After being discharged from Rusk, Rushdie and Eliza moved to a secure location in SoHo, where he continued his physical therapy and slowly regained mobility in his hand. Despite facing additional health scares and permanent physical impairments, Rushdie found joy in resuming social activities and reconnecting with friends.

The process of writing Knife proved therapeutic, allowing him to reclaim his narrative. Although the attack left deep psychological scars, Rushdie and Eliza remained committed to each other and to their shared creative endeavors, including a potential film project.

Ultimately, Rushdie returned to Chautauqua, where he had been attacked, finding a sense of peace and closure.

Through it all, he maintained his commitment to free speech and the pursuit of truth, undeterred by the violence he endured.

Characters

Salman Rushdie

Salman Rushdie, the central figure of Knife, is portrayed as a man of immense resilience and introspection. His life has been shaped by his commitment to free speech and the literary arts.

The attack on him in 2022 serves as a brutal reminder of the dangers that accompany his stance. Yet, it also solidifies his resolve.

Rushdie’s recovery, both physical and psychological, is a testament to his determination to not let violence silence his voice. He is depicted as someone who deeply values human connection, as seen in his gratitude towards those who supported him during his recovery, particularly his wife.

Despite the trauma, Rushdie’s narrative remains laced with a critical examination of religious fundamentalism. He engages in an imagined dialogue with his attacker to explore the roots of such violence.

His reflections on the neutrality of tools, like the knife, extend to language. This emphasizes his belief in the power of words to shape reality.

Rushdie’s journey through the memoir reveals his struggle to come to terms with the attack’s lasting effects, including the loss of vision in one eye. However, it reaffirms his unwavering commitment to the principles that have always guided him.

Rachel Eliza Griffiths

Rachel Eliza Griffiths, Rushdie’s wife, emerges as a pivotal figure in the memoir. She embodies love, support, and resilience.

As a writer and artist, she shares a deep connection with Rushdie. However, their relationship is marked by her discomfort with the public spotlight that comes with being his partner.

Their bond grows stronger through adversity, particularly after the attack. Griffiths’ role in Rushdie’s recovery is not just physical but emotional, providing him with comfort and strength during his most vulnerable moments.

The memoir highlights the sacrifices she makes, such as keeping their relationship private and supporting him through his painful rehabilitation. Her love and dedication are crucial to Rushdie’s ability to find solace and healing in the aftermath of the attack.

Moreover, Griffiths’ involvement in documenting their experience through video and audio recordings signifies her commitment to preserving their shared narrative. This further strengthens their relationship.

Together, they navigate the psychological aftermath of the attack. Her support is portrayed as a cornerstone of Rushdie’s recovery and his eventual return to public life.

Hadi Matar (Referred to as “the A.”)

Hadi Matar, referred to in the memoir only as “the A.,” is the assailant whose attack on Rushdie sets the stage for the narrative. Although Rushdie chooses not to name him directly, “the A.” represents the embodiment of the ideological extremism that Rushdie has long opposed.

The memoir delves into the mind of “the A.” through an imagined dialogue, where Rushdie explores the motivations behind the attack. “The A.” is depicted as a young man radicalized by online propaganda, particularly videos that espouse a fundamentalist interpretation of Islam.

Rushdie portrays him as someone who is deeply confused, lonely, and living in a fantasy world where violence is justified as a service to God. This exploration reveals Rushdie’s critique of religious fanaticism and its ability to warp individual beliefs into acts of terror.

The attacker’s decision to cancel his gym membership before the attack suggests a premeditated acceptance that his life, as he knew it, was over. This reflects the depth of his indoctrination.

Through this character, Rushdie examines the dangers of ideological extremism and the tragic consequences it can have for both the victim and the perpetrator.

Andrew Wylie

Andrew Wylie, Rushdie’s literary agent, plays a crucial role in encouraging Rushdie to channel his trauma into his writing. Known as “The Jackal” in the literary world, Wylie is depicted as a shrewd and persistent figure who understands the power of narrative in healing and reclaiming agency.

His suggestion that Rushdie write a book about the attack, despite Rushdie’s initial reluctance, is instrumental in the creation of Knife. Wylie’s foresight and understanding of Rushdie’s needs as a writer help him see the therapeutic potential of confronting his ordeal through prose.

This relationship underscores the importance of professional and personal support networks in helping individuals navigate and overcome trauma.

Milan Rushdie

Milan Rushdie, Salman Rushdie’s son, represents the continuity of familial love and the generational impact of Rushdie’s experiences. Milan’s presence during Rushdie’s rehabilitation is depicted as a source of strength for his father.

His visits are carefully planned, indicating a deep care for his father’s emotional well-being. They provide Rushdie with much-needed companionship.

Milan’s involvement in his father’s recovery highlights the importance of family in the healing process. It also emphasizes how trauma affects not just the individual but their loved ones as well.

His character is a reminder of the personal stakes involved in Rushdie’s survival and recovery.

Martin Amis

Martin Amis, Rushdie’s dear friend, serves as a symbol of enduring friendship and the personal losses Rushdie has faced over the years. Amis, who was battling cancer at the time, represents the fragility of life and the shared experiences of literary giants who have faced their own struggles.

The significance of their final meetings underscores the emotional depth of Rushdie’s relationships and the importance of these connections in his life. Amis’ death shortly after their meetings adds a layer of poignancy to the memoir, reminding readers of the inevitability of loss and the impact of close friendships on one’s life and work.

Themes

Trauma, Recovery, and the Psychological Impact of Violence

In Knife: Meditations After an Attempted Murder, Salman Rushdie delves deeply into the physical and psychological aftermath of a near-fatal attack. He highlights the profound and multifaceted nature of trauma.

The memoir intricately explores how the violence inflicted upon him extends beyond physical wounds. It permeates his psyche and alters his perception of safety, identity, and the world around him.

Rushdie’s recounting of his recovery process—both bodily and mentally—underscores the long, arduous journey that follows such a traumatic event. His sense of vulnerability and the loss of autonomy over his body, exemplified by his difficulty in accepting the partial loss of vision and the paralysis in his mouth, reflect a broader theme of how trauma disrupts one’s sense of self.

The memoir suggests that the psychological scars of violence can be as enduring, if not more so, than the physical ones. Rushdie navigates the complexities of his new reality, haunted by the memory of the attack.

His reflections reveal a deep struggle to reclaim his sense of agency. There is also a poignant acknowledgment of the permanent changes that trauma has wrought on his life.

The Intersection of Art, Free Speech, and Violence

Rushdie’s memoir is a powerful meditation on the inextricable link between artistic expression, free speech, and the violence that can arise when these freedoms are challenged. The attack on Rushdie is not merely a personal assault but a symbol of the broader, ongoing struggle over the right to speak and create freely in the face of oppressive forces.

Through his reflection on the attack and his previous work, particularly The Satanic Verses, Rushdie reaffirms his belief in the necessity of challenging orthodoxies. He highlights the role of art in pushing boundaries.

He articulates the dangers faced by artists and writers who dare to question and critique powerful institutions, such as religion, and the heavy price they may pay for exercising this freedom. The memoir situates the attack within a larger context of historical and ongoing efforts to silence dissenting voices, drawing connections to other instances of censorship and violence against writers.

Rushdie’s steadfast commitment to free speech, even after experiencing such brutality, underscores the fundamental importance he places on the freedom to create and express ideas. This remains true no matter how controversial or provocative they may be.

The Personal as Political: Love, Relationships, and Resilience

Rushdie’s relationship with his wife, Rachel Eliza Griffiths, is portrayed as a sanctuary and source of strength amidst the chaos of his recovery. It illustrates the theme of love as a counterforce to violence and trauma.

The memoir emphasizes the crucial role that personal relationships play in the process of healing. Eliza’s unwavering support provides Rushdie with the emotional and psychological fortitude needed to confront his ordeal.

The narrative of their relationship—beginning with their serendipitous meeting and culminating in their deepened bond after the attack—serves as a testament to the resilience of human connection in the face of adversity. Moreover, Rushdie’s portrayal of their relationship also highlights the complexities of love when placed under extraordinary strain, as both he and Eliza grapple with the psychological impact of the attack.

The memoir suggests that love, while not a panacea for the wounds of violence, offers a vital form of resistance against the forces that seek to dehumanize and destroy. In this way, Rushdie frames his personal life as inherently political, where the intimacy of love and the struggle to maintain it becomes a quiet yet profound act of defiance against the terror that sought to silence him.

The Weaponization of Religion and the Radicalization of Youth

Rushdie’s exploration of his attacker’s motivations opens a broader discussion on the weaponization of religion and the process of radicalization. The memoir delves into the psychological and social mechanisms that transform religious belief into a justification for violence, particularly in young, disillusioned individuals like his attacker.

By dissecting the attacker’s mindset, which was shaped by extremist propaganda, Rushdie engages with the theme of how religion can be manipulated to serve violent ends. This distorts faith into a tool for terror.

This theme is particularly resonant in the context of Rushdie’s own history with religious fundamentalism, notably the fatwa issued against him after the publication of The Satanic Verses. Rushdie’s reflections underscore the tragic consequences of such radicalization, not only for the victims of violence but also for the perpetrators, who are often themselves casualties of a pernicious ideological war.

The memoir critiques the simplistic narratives that cast such violence as the result of pure evil. Instead, it offers a nuanced examination of how religious ideology can be exploited to manipulate vulnerable individuals, leading them down a path of destruction.

Through this, Rushdie highlights the broader societal responsibility to address the root causes of radicalization. He also calls for challenging the ideological structures that enable such violence.

The Philosophical and Ethical Implications of Survival

In the wake of the attack, Rushdie grapples with the existential questions that arise from his survival. He ponders the philosophical and ethical implications of living after such a near-death experience.

The memoir reflects on the randomness of violence and the arbitrary nature of survival, where Rushdie’s continued existence is as much a matter of chance as it is of medical intervention. This theme invites a deeper contemplation of the value of life and the ethical responsibilities that come with surviving an attempt on one’s life.

Rushdie’s survival becomes a space for exploring questions of destiny, fate, and the meaning of life in a world where violence can strike unpredictably. His reflections reveal a tension between gratitude for being alive and the burden of living with the consequences of the attack, including the loss of normalcy and the constant awareness of his own mortality.

The memoir suggests that survival is not just a biological state but a complex ethical condition, requiring a re-evaluation of one’s purpose and actions in the aftermath of trauma.

Rushdie’s resolve to continue writing and engaging with the world, despite the profound changes in his life, speaks to a philosophical resilience, where survival is not just about enduring but about finding new meaning and direction in a world irrevocably altered by violence.