Slow Productivity Summary and Analysis

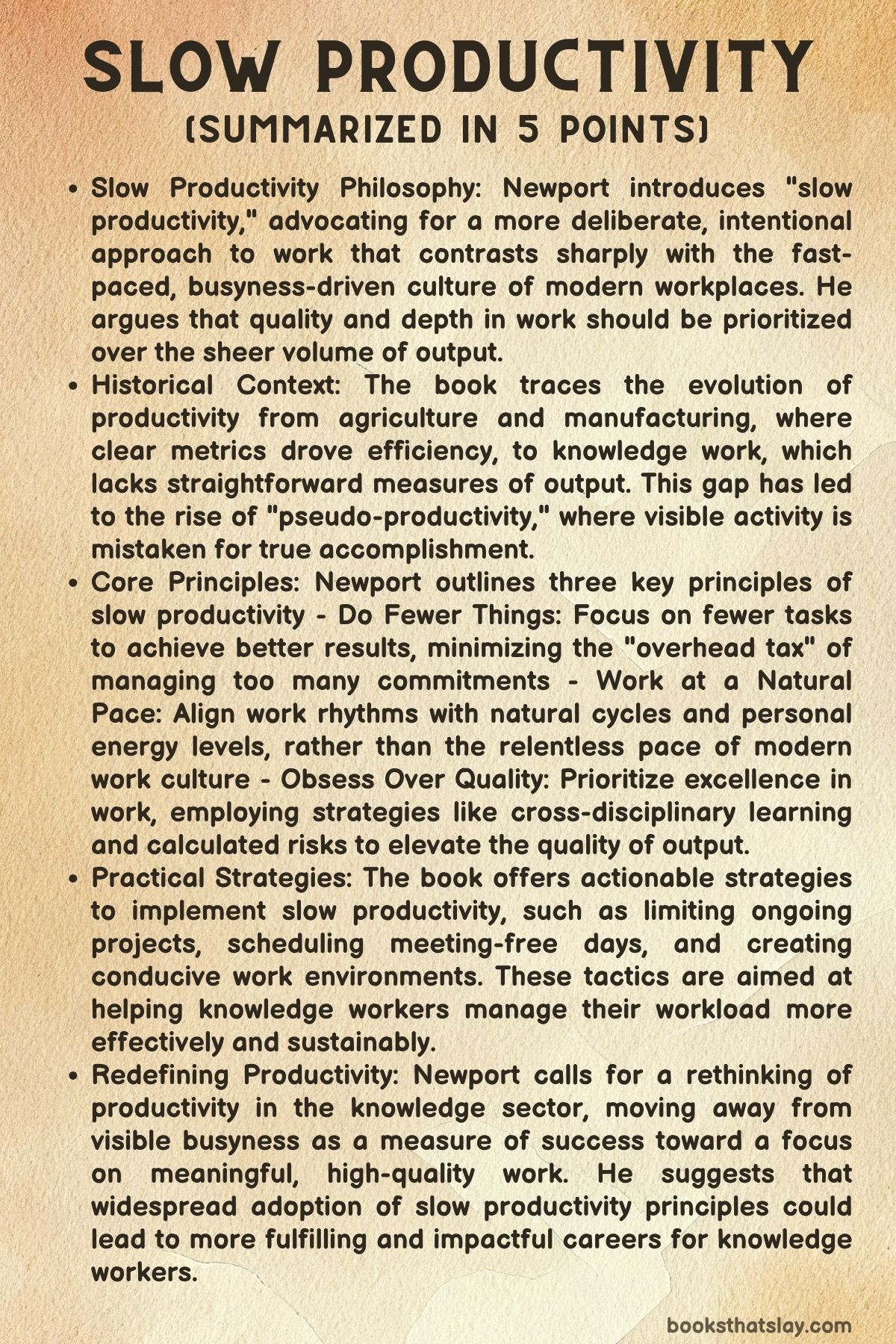

“Slow Productivity: The Lost Art of Accomplishment Without Burnout” by Cal Newport is a transformative guide to sustainable work practices in the modern age. Known for his influential books like “Deep Work” and “A World Without Email,” Newport challenges the current obsession with busyness and productivity metrics.

In this book, he advocates for a slower, more intentional approach to work that prioritizes quality over quantity. Newport’s philosophy is designed to help knowledge workers achieve meaningful accomplishments without falling into the trap of burnout, offering practical strategies that promote well-being and lasting success.

Summary

In “Slow Productivity,” Cal Newport introduces a radical shift in how we think about work. He starts by critiquing the fast-paced, overburdened nature of modern workplaces, which often prioritize busyness over actual productivity.

Newport contrasts this with the thoughtful, deliberate working style of writer John McPhee, who once spent two weeks just planning the structure of an article. This example sets the stage for Newport’s argument that the relentless drive for constant output, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, has led to detrimental work trends like the Great Resignation and “quiet quitting.”

Newport calls for a new definition of productivity that values depth and intentionality over mere activity.

The book is divided into two main parts.

In the first part, Newport traces the history of productivity from agricultural practices to the rise of manufacturing, illustrating how clear metrics once drove efficiency in these sectors. For example, he explains how the Norfolk four-course crop rotation system revolutionized agriculture and how Henry Ford’s assembly line transformed car production.

However, Newport points out that knowledge work lacks such straightforward measures of output, leading to what he calls “pseudo-productivity,” where visible busyness is often mistaken for real productivity.

To counter this trend, Newport proposes an alternative model inspired by the Slow Food movement, which emphasizes quality over speed.

He suggests that the principles of slow productivity, drawn from the work habits of historical figures in writing, science, and the arts, can offer valuable lessons for today’s knowledge workers.

In the second part of the book, Newport outlines the three core principles of slow productivity. The first principle, “Do Fewer Things,” advocates for reducing the number of commitments to improve focus and results.

Newport introduces the idea of the “overhead tax,” which refers to the administrative burden that comes with each new task. He provides practical strategies for simplifying workloads, such as limiting ongoing projects and implementing tools like “office hours” and “docket-clearing meetings” to manage smaller tasks efficiently.

The second principle, “Work at a Natural Pace,” encourages a slower, more sustainable rhythm of work.

Newport contrasts modern work’s frantic pace with historical examples like Copernicus and Newton, who worked at their own pace. He suggests strategies for creating “small seasonality” in work schedules, such as setting aside meeting-free days and taking regular breaks.

Newport highlights the importance of aligning work environments with the nature of the task, citing examples like Lin-Manuel Miranda, who wrote parts of Hamilton in a historic mansion, and Neil Gaiman, who built a writing shed in the woods.

The third principle, “Obsess Over Quality,” emphasizes the importance of focusing on excellence rather than mere output.

Newport suggests strategies for enhancing the quality of work, including cross-disciplinary learning and seeking peer feedback.

He also introduces the concept of “betting on” oneself—taking calculated risks to elevate one’s work to a higher level, whether through passion projects or more significant career shifts.

In the conclusion, Newport revisits John McPhee’s meticulous writing process as a model for slow productivity.

He reiterates the book’s central message: that by adopting slow productivity practices, individuals can achieve more meaningful and impactful work while avoiding burnout.

Newport calls for a rethinking of how productivity is measured and organized in the knowledge sector, proposing a shift from visible busyness to genuine, high-quality output.

Through this reimagined approach, Newport envisions a more sustainable and fulfilling work life for millions of knowledge workers.

Key Lessons

The Historical Context of Productivity and Its Misapplication in Knowledge Work

One of the core lessons in Cal Newport’s Slow Productivity is the deep examination of the historical evolution of productivity. Newport meticulously traces productivity’s roots, showing how clear metrics and tangible outputs fueled innovations like the Norfolk four-course crop rotation system and Henry Ford’s assembly line.

However, he argues that these same metrics are ill-suited for the complex and often intangible nature of knowledge work. In traditional sectors, productivity improvements were visible and measurable, often linked directly to physical outputs. In contrast, the value of knowledge work is far more abstract, relying heavily on creativity, deep thought, and intellectual synthesis—qualities that cannot be easily quantified or optimized through the same mechanisms used in manual labor.

This misapplication has led to what Newport calls “pseudo-productivity,” where the appearance of busyness or activity is mistaken for true productivity. The relentless pace and constant activity that characterize modern knowledge work are, in Newport’s view, superficial indicators that do not necessarily lead to meaningful results.

Instead, they often result in burnout and diminished quality of work. Newport suggests that this disconnect between the nature of the work and the methods used to measure it is at the heart of many modern productivity issues, exacerbating stress and reducing overall effectiveness.

The Overhead Tax and the False Economy of Busyness

Newport introduces a sophisticated concept he terms the “overhead tax,” which refers to the administrative and cognitive burdens that accompany every new commitment or task. This concept challenges the conventional wisdom that taking on more projects or tasks necessarily leads to greater productivity or success.

Instead, Newport argues that each additional responsibility comes with hidden costs, including time spent managing tasks, switching between different types of work, and the mental load of keeping track of numerous obligations. These overhead costs can quickly add up, leading to a significant reduction in overall productivity and quality of work.

Newport’s analysis goes beyond the simple idea of “doing less” by providing a nuanced understanding of how even seemingly small commitments can create substantial drag on one’s cognitive resources. He highlights that in the modern work environment, where multitasking and constant connectivity are often celebrated, the overhead tax can be particularly insidious.

It erodes the time and mental energy that could otherwise be dedicated to deep, focused work, leading to a situation where workers are busy but not necessarily productive. Newport’s insight into the overhead tax serves as a critical reminder that true productivity is not about maximizing output but about minimizing unnecessary burdens to focus on high-impact activities.

The Principle of Slow Work Rhythms and the Rejection of Linear Time Management

Newport’s exploration of “working at a natural pace” offers a profound critique of contemporary time management practices, which often emphasize linearity and efficiency. He contrasts these modern methods with historical examples of slow work rhythms, such as the deliberate pace at which Copernicus and Newton pursued their scientific inquiries.

Newport argues that the current obsession with maximizing every minute of the workday is counterproductive, particularly in fields that require creativity and deep thought. Instead of adhering to rigid schedules and constant output, Newport advocates for a more fluid approach to time management, one that aligns more closely with the natural rhythms of the work itself.

This could involve embracing “small seasonality” in work schedules—periods of intense focus followed by intervals of rest or different types of activities. For example, Newport suggests that workers could designate specific days for deep work, free from meetings and interruptions, or take regular breaks to refresh their minds.

This approach not only reduces the risk of burnout but also allows for a more organic development of ideas and projects. By rejecting the linear, assembly-line approach to time management, Newport posits that knowledge workers can achieve greater creativity and produce higher-quality work.

This lesson challenges the deep-seated notion that more time spent working equals more productivity, proposing instead that strategic periods of rest and varied work rhythms are essential for sustainable productivity.

The High-Stakes Commitment to Quality and the Concept of “Betting on Yourself”

A particularly challenging lesson in Newport’s framework is his emphasis on the need to “obsess over quality,” even when it requires taking significant personal or professional risks—a concept he encapsulates as “betting on yourself.” Newport argues that in an environment where quantity often trumps quality, making a deliberate choice to focus on excellence can be both daunting and transformative.

He draws on examples from music, literature, and science to illustrate how a commitment to quality often involves high stakes. Whether it’s an artist investing time in a passion project or a professional taking a pay cut to focus on more meaningful work, the decision to prioritize quality can be life-changing.

This lesson is particularly tough because it involves a fundamental shift in how one approaches their career and work. Newport suggests that truly exceptional work requires more than just time and effort; it requires a willingness to take risks, to potentially sacrifice immediate rewards for long-term gains.

This might involve reducing one’s workload to focus on a single project, quitting a stable job to pursue a passion, or investing in cross-disciplinary learning to enhance the depth and breadth of one’s expertise.

Newport’s concept of “betting on yourself” challenges the prevailing culture of safety and incremental progress in many careers. Instead, he advocates for bold moves that prioritize the pursuit of excellence over the accumulation of accolades or the comfort of steady employment.

This lesson underscores the idea that slow productivity is not about doing less for the sake of it, but about creating the conditions under which truly great work can emerge, even if it means taking substantial risks along the way.

The Reimagining of Productivity Systems for the Knowledge Economy

In the conclusion of Slow Productivity, Newport pushes the reader to think beyond individual strategies and consider the broader implications of adopting slow productivity principles at an organizational and societal level. He critiques the current productivity systems that dominate the knowledge economy, arguing that they are outdated and often counterproductive.

Newport envisions a marketplace of productivity ideas where different approaches are explored and tested. These range from immediate, actionable changes in work habits to more ambitious reforms in organizational structures and policies.

This lesson is particularly complex because it involves a rethinking of deeply ingrained systems and practices. Newport challenges both individuals and organizations to move away from the superficial metrics of busyness and visible activity, which often serve as proxies for actual productivity.

Instead, he advocates for a more thoughtful and deliberate approach, where the quality of output and the well-being of workers are prioritized over mere activity levels. Newport’s call for a reimagined productivity system is not just a personal or professional challenge but a societal one.

It requires a shift in how success is measured, how work is organized, and how individuals are rewarded. This lesson is about envisioning a future where the principles of slow productivity are not just a personal choice but a foundational aspect of how knowledge work is structured and valued.

Newport’s vision is ambitious, requiring a collective effort to rethink and redesign the systems that govern modern work. However, it offers a path toward a more sustainable and meaningful approach to productivity in the knowledge economy.