How to Say Babylon Summary, Analysis and Key Themes

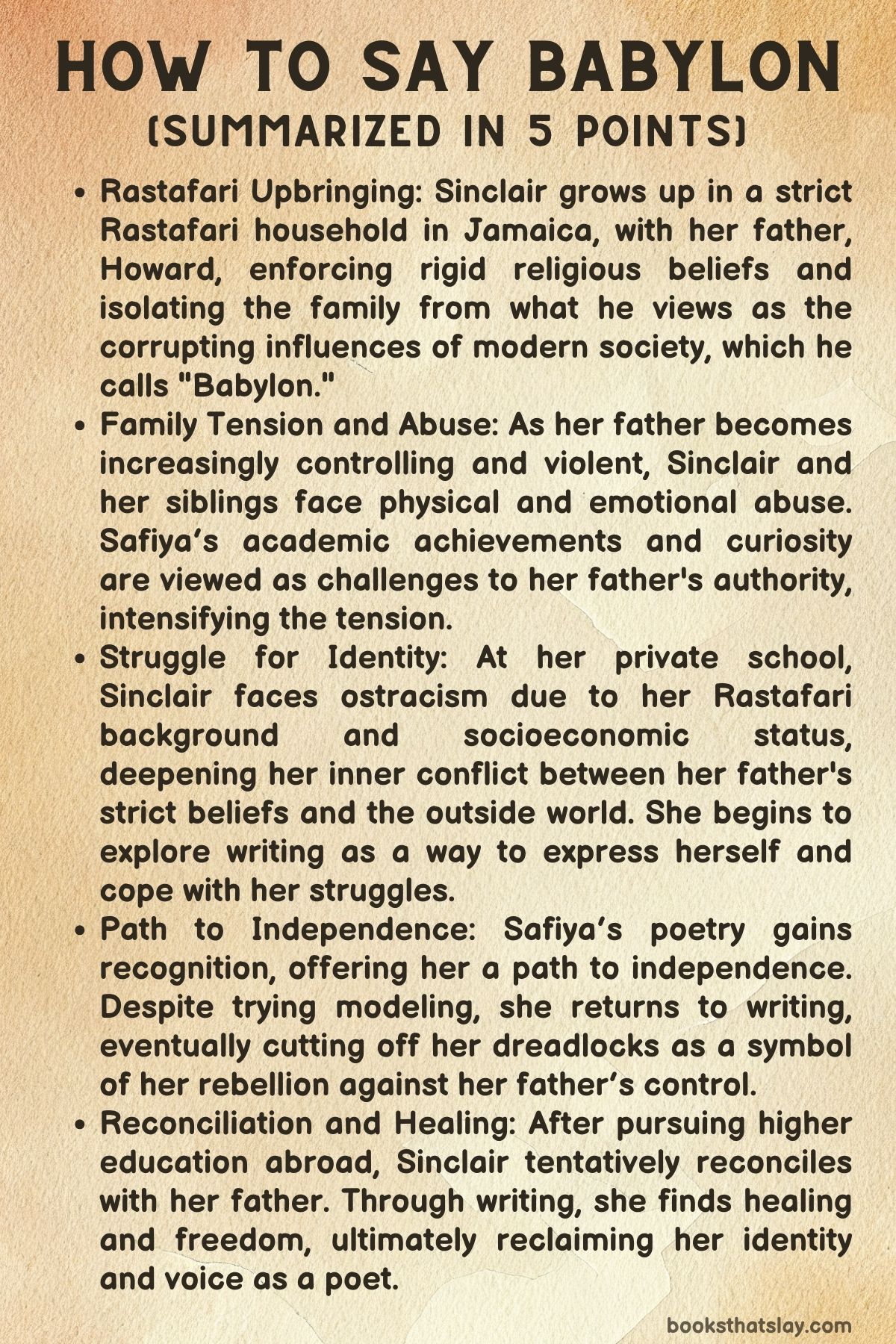

How to Say Babylon is a deeply reflective memoir by Safiya Sinclair, a Jamaican poet whose journey through a strict Rastafari upbringing reveals a powerful tale of self-discovery. Published in 2023, Sinclair recounts her childhood in rural Jamaica, where her father’s rigid beliefs shaped much of her early life.

Struggling against his increasing control and the violent dynamics at home, she finds solace in writing and poetry. Through her words, Sinclair crafts a path to freedom, navigating her way from a repressive household to the broader world beyond, offering a poignant meditation on identity, resilience, and reconciliation.

Summary

In the early chapters of the memoir, Safiya Sinclair reflects on her childhood in Jamaica, which at first seems idyllic. She grows up in a picturesque coastal village alongside her two younger siblings, Lij and Ife, under the care of their mother, Esther, while their father, Howard, is often away pursuing his Rastafari-influenced music career.

However, Howard’s deep distrust of modern society, which he refers to as “Babylon” in keeping with Rastafarian belief, leads him to relocate the family to a remote countryside, seeking isolation from corrupting influences. This move coincides with the birth of Safiya’s youngest sister, Shari.

Howard later departs for Japan to further his music career, but his return is marked by bitterness and failure. The once-distant father becomes more present in the family’s daily life, but his presence brings tension.

As Safiya enters adolescence, her father’s growing paranoia about Babylon leads to more rigid control over his children. While Safiya excels academically and even earns a scholarship to a private school, Howard’s increasingly harsh discipline overshadows these achievements.

He views her curiosity and success as potential threats, planting seeds of tension and resentment.

As Safiya attends her new school, she feels alienated. Her Rastafari background and modest family circumstances set her apart from her wealthier classmates, who mock and belittle her.

This period marks the start of a growing inner conflict for Safiya—caught between her father’s strict ideals and the demands of the modern world, she turns to poetry for solace.

Amid her father’s escalating physical abuse, her mother Esther takes on more work outside the home, leaving Safiya to contend with Howard’s outbursts. The cracks in Howard’s stern façade become clearer to Safiya, as she realizes her father is neither infallible nor divine, as she once believed.

Safiya’s poetry begins to flourish, with her work being accepted by the Jamaica Observer. Encouraged by this validation, she deepens her focus on writing, finding it to be a means of escape.

Through her mentorship with an experienced poet, her creative voice grows stronger, yet she also ventures into modeling as an alternate path to independence.

Her success in the modeling industry is limited by her dreadlocks—a symbol of her faith but a hindrance to marketability.

Returning to Jamaica after a brief stint in the U.S., Safiya faces increasing verbal abuse from Howard.

Her eventual rebellion comes in the form of cutting off her dreadlocks, an act that enrages Howard but also marks a turning point for her own autonomy.

Inspired by a trip abroad with Esther, both women gradually distance themselves from Howard’s oppressive grip.

Parting ways with Howard, Safiya eventually pursues higher education in the U.S. and begins to reclaim her life.

Even as her nightmares of her father persist, time and distance allow for tentative reconciliation. When Safiya returns to Jamaica for a poetry reading, she and Howard share a fragile but meaningful moment of connection, signaling a bittersweet closure to her tumultuous past.

Through writing, Safiya finds both healing and freedom, embracing her voice and story.

Analysis and Characters

The Intersection of Patriarchy, Religion, and Control in the Rastafari Context

One of the central themes of How to Say Babylon is the oppressive intersection of patriarchal control, religion, and authority as embodied by Sinclair’s father, Howard. His strict adherence to Rastafari beliefs, particularly its conservative and often patriarchal interpretations, becomes a tool for exerting dominance over his family, particularly the women in his household.

The memoir reveals how religious dogma is manipulated to justify Howard’s oppressive behavior and authoritarianism, restricting Safiya and her mother’s autonomy. Sinclair captures how her father’s fears of “Babylon”—the modern, corrupting world—serve to enforce isolation, submission, and the repression of personal desires.

His interpretation of Rastafari becomes a means of not just spiritual guidance but also a mechanism of control, steeped in patriarchal expectations. Howard’s increasing obsession with purity and spiritual superiority creates a climate where any challenge to his authority—especially from Safiya, as she matures and begins to question his teachings—becomes grounds for violence.

This theme extends beyond religious extremism to address broader questions of how patriarchal ideologies can intersect with spiritual belief systems to enforce dominance and subjugation.

The Burden of Cultural Alienation and Socioeconomic Inequality in Colonial Jamaica

Through Safiya’s experience at her elite private school, Sinclair addresses the complexities of cultural alienation and socioeconomic inequality in post-colonial Jamaica. The stark division between her Rastafari upbringing and the privileged world of her wealthier classmates highlights the class divides that persist in Jamaican society.

This tension is intensified by the lingering effects of colonialism, which continues to shape societal hierarchies, values, and expectations. Sinclair’s Rastafari identity marks her as “other” in an environment where European standards of beauty and success dominate, leaving her feeling inferior and excluded.

Her dreadlocks, a symbol of her faith, are seen as an obstacle in both her academic and later modeling career. This underscores the way cultural markers of her identity clash with the wider world’s expectations.

The memoir subtly critiques how class and colonial legacies affect identity formation, especially for someone like Sinclair, who is caught between the traditions of her family and the aspirations of the broader, often Westernized world.

The Creative Power of Poetry as a Means of Rebellion and Healing

Safiya’s discovery of poetry serves not just as an outlet for self-expression, but as a profound act of rebellion against her father’s control and the rigid boundaries of her world. Poetry becomes both a means of survival and a method of subverting the forces that seek to silence her.

It allows her to navigate the emotional turbulence of her father’s abuse and her feelings of alienation, providing a mental escape from the confines of her isolated life. Her growing success as a poet represents her slow, but deliberate, defiance against the oppressive forces in her life, marking her growing independence.

This theme also speaks to the broader concept of art as resistance, especially in contexts where individual agency is suppressed by both familial and cultural expectations. Through poetry, Sinclair not only reclaims her voice, but she also carves out a space where she can critique and reflect on the patriarchal structures that have shaped her existence.

It is through her writing that she ultimately finds both emotional and physical freedom.

The Complex Interplay of Trauma, Memory, and Reconciliation in Familial Relationships

Sinclair’s memoir reveals the lasting impacts of trauma, particularly how physical and emotional abuse from a parent shapes identity, memory, and future relationships. Howard’s violent outbursts leave deep emotional scars, manifesting in Safiya’s later struggles with nightmares and feelings of fear long after she has physically escaped his control.

However, the theme of trauma is intricately linked to that of reconciliation. Over time, as Howard grows older and more reflective, there is a softening in his character, and the memoir grapples with the difficult process of reconciling with someone who has caused profound harm.

Safiya’s ultimate attempt to come to terms with her father’s abuse highlights the complexity of familial love, where forgiveness exists alongside unresolved pain. The reconciliation between father and daughter is tenuous and incomplete, reflecting how trauma’s echoes can never fully be silenced.

Yet, the memoir suggests that while reconciliation may not erase the trauma, it is a necessary step in healing and finding peace.

The Intersectionality of Gender, Race, and Religious Identity in the Quest for Personal Freedom

Safiya’s journey is not just about escaping the confines of her father’s authoritarianism, but also about navigating the multiple, intersecting identities that shape her experience. These include being a Black woman, a Rastafari, and a poet in a world that seeks to constrain her at every turn.

The memoir explores how each of these aspects of her identity imposes different forms of societal expectations and limitations. Sinclair must negotiate them in her search for freedom.

Her experience as a Rastafari woman is fraught with gendered restrictions. Her race and dreadlocks affect her prospects in the United States and in modeling, while her identity as a poet challenges traditional roles expected of women within her community.

The memoir thus engages with broader discourses of intersectionality. It shows how Sinclair’s path to autonomy is a complex negotiation of cultural, gendered, and racial dynamics.

Her decision to cut off her dreadlocks—historically a symbol of resistance for Rastafari people—further complicates this intersectionality. It is both an act of rebellion against her father’s control and a painful renunciation of a part of her cultural heritage.

This act encapsulates the difficult choices women like Sinclair must make in their quest for personal agency and self-determination.

The Tension Between Tradition and Modernity in a Globalized World

Howard’s fear of Babylon symbolizes a deep conflict between tradition and modernity, a theme that Sinclair unpacks in the context of globalization’s impact on Jamaica and her family. Howard’s increasing paranoia about the corrupting influence of the modern world leads him to retreat into more extreme forms of Rastafari conservatism.

He positions his beliefs in stark opposition to the forces of change represented by technology, media, and Western values. For Safiya, however, modernity becomes a space of liberation—a realm where her poetry can flourish and where she can break free from the rigid gender roles and cultural expectations imposed by her father’s Rastafari worldview.

The memoir thus becomes a narrative of generational conflict, where the old ways, represented by Howard, clash with the possibilities of the new. The struggle between tradition and modernity is not just ideological, but deeply personal, as Safiya must navigate her father’s fears of cultural loss while simultaneously forging her own path in a world he views as dangerous and corrupting.

The memoir suggests that modernity, for all its imperfections, offers a crucial means of escape from oppressive structures, while also acknowledging the profound sense of displacement that can accompany such a break from tradition.