The Vaster Wilds Summary, Characters and Themes

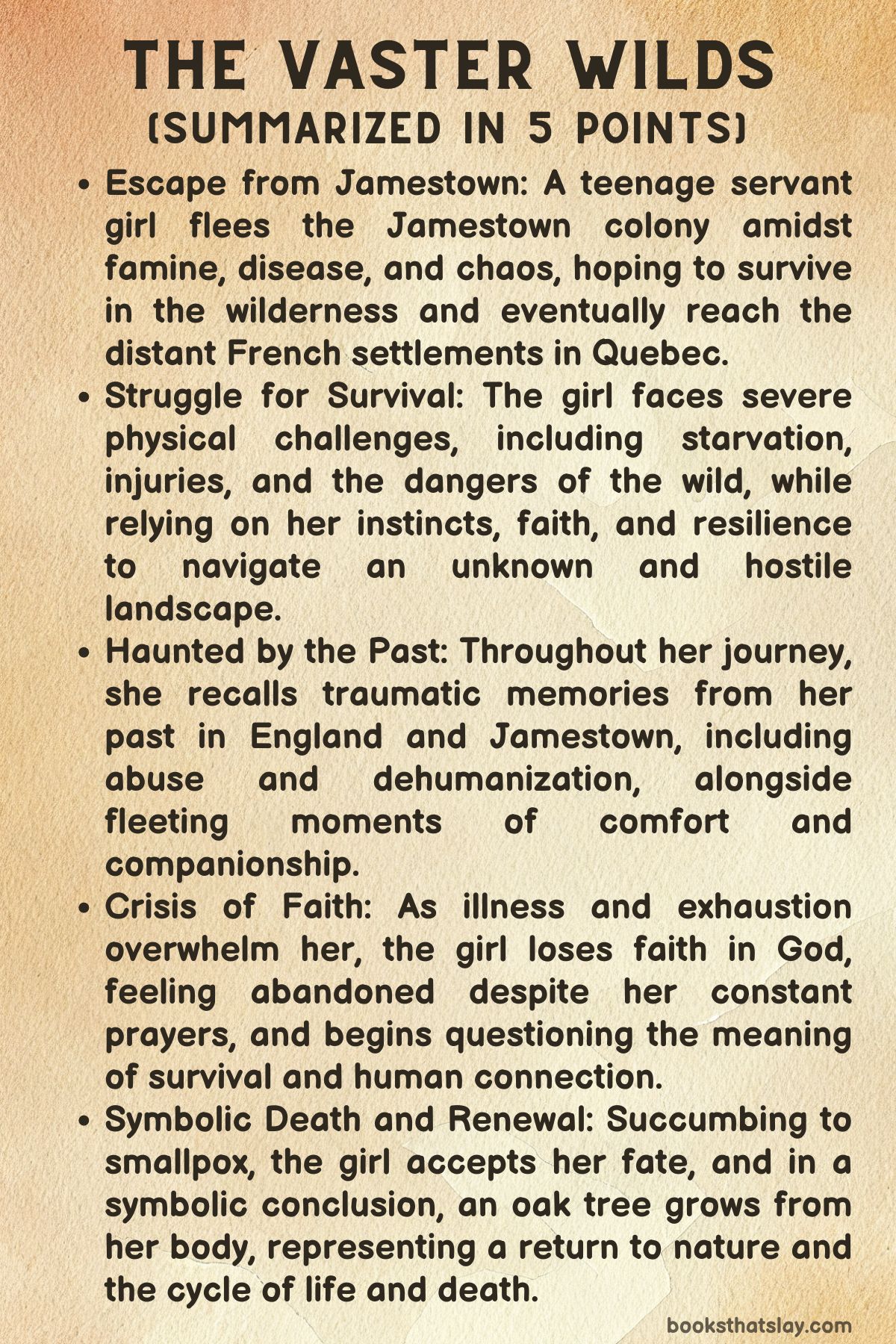

The Vaster Wilds by Lauren Groff is a gripping survival-adventure novel set against the harsh backdrop of early colonial America. It follows the harrowing journey of a young servant girl who escapes from the doomed Jamestown settlement, fleeing into an untamed wilderness.

Faced with the relentless challenges of survival—starvation, illness, and a hostile environment—she must rely on her instincts and inner strength to endure. Blending historical fiction with philosophical reflections on nature, faith, and human connection, Groff weaves a compelling narrative about perseverance, trauma, and the fragile balance between isolation and companionship.

Summary

In the dead of a bitter winter night, a teenage servant girl makes a daring escape from the Jamestown settlement, where the colonists are ravaged by disease, famine, and violent internal strife.

The settlement has become a deathtrap, and in her desperation, she chooses the uncertainty of the wilderness over the certainty of death within the fort’s walls.

Her goal is to find her way to the distant French colonies in what would later become Quebec, though her understanding of the land is limited by the perspective of a European colonist who has little knowledge of the wild terrain.

The girl’s struggle for survival begins immediately, as the wilderness offers no mercy. Her journey is marked by an unending fight for sustenance, where each meager meal comes as a hard-won victory—honey scavenged from a hive, fish drawn from frozen waters, or grubs dug from decaying wood.

Injuries and exposure to the elements sap her strength, and the constant threat of predators like wolves and bears adds to her fears. But her most persistent adversary is the unknown itself—the vast, indifferent wilderness that surrounds her, filled with dangers both real and imagined.

She is haunted by terrifying visions of monsters and death, her mind growing ever more fragile as hunger and isolation take their toll.

Throughout her ordeal, she reflects on her past, her memories serving as brief respites from the brutality of her present reality. Her childhood in an English poorhouse was marked by hardship, and after being taken into service by her mistress, her life was one of relentless dehumanization.

Flashbacks reveal the abuse she endured at the hands of her mistress’s son and the horrors of being locked in a room with the plague-stricken husband of her mistress.

These traumatic experiences are interspersed with fleeting moments of warmth, including a brief love affair with a Dutch sailor during her sea voyage to America, whose imagined presence becomes a source of comfort during her lonely trek.

As her journey progresses, the girl’s physical and mental state deteriorates. She begins to have fevered dreams and hallucinations, imagining herself with a savior from the French settlements or building a life in the wilderness with the sailor she loved.

But these fantasies grow dim as she becomes more attuned to the harsh reality around her.

Eventually, her body succumbs not to the elements or wild beasts, but to smallpox—a disease carried from the Old World, and one she can’t escape. As her fever intensifies, she experiences a crisis of faith, feeling abandoned by God despite her fervent prayers for deliverance.

In the moments before her death, she imagines an alternative life in which she heals and lives in harmony with nature, but realizes that true fulfillment requires both human connection and an appreciation of the natural world.

In her final moments, she feels a profound connection to the earth, and after her death, her body gives rise to new life as an oak tree sprouts from her ribcage—a final symbol of renewal and continuity.

Characters

The Girl (Protagonist)

The central character of The Vaster Wilds is a nameless teenage servant girl who escapes from the doomed Jamestown settlement. As a protagonist, she is both physically and mentally resilient, capable of enduring extreme hardship and deprivation in the unforgiving wilderness.

Her escape is motivated by desperation, fueled by her experiences of dehumanization and trauma in the colony. The novel intricately reveals her past, including the abuse and mistreatment she suffered at the hands of her mistress’s son and the horrors of being locked away with a plague-ridden man.

These experiences shape her into a figure hardened by survival and accustomed to cruelty. Yet, beneath her pragmatic exterior, the girl harbors deep emotions, yearning for connection and tenderness, as seen in her memories of a brief romantic encounter with a Dutch sailor.

Her perseverance is not only physical but deeply rooted in her spirituality, as her faith in God sustains her throughout much of the novel. However, this faith wavers as she faces the growing isolation, disease, and fear of death in the wilderness.

The girl’s journey is both literal and metaphorical, with the wilderness representing her confrontation with her own fears, loss of innocence, and struggle for agency in a world that has consistently denied her autonomy.

The Dutch Sailor

Although the Dutch sailor only appears in the girl’s flashbacks and fevered hallucinations, he plays a vital role in her internal world. He represents a rare moment of love, intimacy, and freedom in her otherwise bleak existence.

During their brief relationship on the sea voyage to America, the girl experiences a sense of belonging and emotional warmth, which starkly contrasts with the dehumanization she has known in the rest of her life. His sudden disappearance during a storm, when he is swept overboard, creates an unresolved longing within her.

Throughout her journey in the wilderness, she imagines him as a companion, a protector, and someone who could have offered her a different life. These fantasies offer her solace, but they also reveal the depth of her loneliness and her craving for human connection.

Ultimately, the Dutch sailor becomes an idealized figure, embodying her hopes for a life she can never have, and his presence in her mind fades as she grows more attuned to the harsh realities of her survival.

The Mistress and Her Family

The girl’s relationship with her mistress and the mistress’s family is central to understanding her past traumas.

The mistress is a domineering and cruel figure, treating the girl more like a pet or a piece of property than a human being. This dynamic reflects the broader hierarchical and oppressive structures of colonial society, where servants and lower-class individuals were often stripped of their dignity.

The mistress’s son, from her first marriage, further complicates this dynamic by subjecting the girl to sexual abuse, a trauma that haunts her throughout her journey in the wilderness.

These experiences of exploitation and abuse solidify the girl’s sense of isolation, shaping her perception of human relationships as inherently dangerous.

The cruelty of the family underscores the harshness of the girl’s former life in Jamestown, and their treatment of her explains her willingness to risk death in the wilderness rather than remain in their oppressive grasp.

The Imagined French Savior

The French savior is another figure who exists only in the girl’s imagination, a reflection of her hope for rescue and redemption.

He represents the possibility of salvation, not just in the physical sense of reaching safety in the French colonies, but in the broader sense of being delivered from her suffering. The Frenchman embodies the girl’s fantasy of a more compassionate and just world, one in which she is not dehumanized or exploited but valued.

Throughout her journey, she clings to the idea of this savior, imagining him coming to her aid when she feels most vulnerable or close to death. However, as her physical and mental state deteriorates, she gradually loses faith in this imagined rescue, mirroring her loss of faith in God and the collapse of her belief in external deliverance.

The imagined French savior thus symbolizes the girl’s shifting relationship with hope and despair, and his eventual disappearance from her thoughts marks a turning point in her acceptance of her fate.

God

Though not a character in the traditional sense, God plays a significant role in the girl’s internal life, serving as both a source of comfort and conflict. Her faith is a central aspect of her identity, and for much of the novel, she believes that her survival is a reflection of God’s will.

She prays frequently, asking for deliverance from her suffering, and her faith gives her strength in moments of extreme hardship. However, as she grows more ill and her situation becomes increasingly dire, she begins to feel abandoned by God.

This crisis of faith reflects the broader themes of the novel, particularly the tension between human perseverance and the indifferent forces of nature. In the final stages of her journey, the girl’s loss of faith parallels her physical decline, culminating in a moment of spiritual revelation where she feels a new connection to the natural world, unmediated by the structures of organized religion.

This transition from faith to a more pantheistic understanding of the world reflects her inner transformation as she reconciles herself with her fate and the natural cycle of life and death.

The Wilderness

While not a human character, the wilderness itself plays an integral role in the novel, shaping the girl’s journey and serving as a constant antagonist.

It is vast, unpredictable, and at times terrifying, representing both the physical dangers of survival and the unknown forces that the girl cannot control or fully comprehend. Her fear of the wilderness is compounded by her colonial mindset, which views the land as something to be conquered or tamed.

As she ventures deeper into it, the wilderness becomes a reflection of her inner struggles, challenging her with its indifference to human life.

Over time, the wilderness also becomes a source of beauty and wonder for the girl, a place where she experiences moments of awe despite her suffering. By the end of the novel, her relationship with the wilderness shifts from one of fear and resistance to acceptance, as she comes to understand her place within its cycles.

The wilderness thus functions as both a literal setting and a symbolic force, shaping the girl’s transformation and ultimate reconciliation with her fate.

Themes

The Fragility of Colonialism and the Dissonance of Displacement

One of the novel’s most compelling themes is the dissonance that emerges from the girl’s colonial understanding of the world she inhabits. Her struggle for survival is complicated not merely by the physical challenges of the wilderness, but by her ingrained colonial mindset that fails to adapt to the land around her.

This speaks to a broader critique of the colonial project, which imposed European ideologies, hierarchies, and expectations onto a land that required entirely different modes of existence. The girl’s journey becomes symbolic of the broader failure of colonists to comprehend the environments they sought to dominate.

Her inability to seek help from Indigenous peoples, driven by both fear and arrogance, highlights how colonialism fosters not only physical displacement but also a psychological alienation. This alienation divorces the colonizers from the land they attempt to inhabit, resulting in a fraught and perilous existence.

The girl’s escape from Jamestown is less a flight toward freedom and more a headlong rush into an even deeper crisis of survival. She carries the colonial mindset with her, even as it proves increasingly insufficient to meet her needs.

The Tension Between Survival Instincts and Human Compassion

Groff’s exploration of survival is not simply a physical journey; it is also a moral and emotional one. Throughout the novel, the girl is confronted with the tension between the sheer will to survive and the need for human connection.

The protagonist’s determination to push forward is admirable, yet it comes at the cost of human compassion. She repeatedly chooses self-preservation over any possibility of community, be it with Indigenous peoples or fellow colonists.

Her avoidance of others stems from fear and the internalization of the violence she witnessed in the colony. Yet it also reflects a deeper question: Can true survival exist without empathy and connection?

The girl’s gradual understanding that a fulfilling life must involve both nature and companionship suggests that the human spirit requires more than mere physical survival. It demands moral and emotional sustenance.

Her vision of an isolated, self-sufficient life eventually collapses, revealing the hollow core of such an existence.

The Descent into Psychological Disintegration and Hallucinatory Escapism

As the girl’s journey unfolds, her physical decline is paralleled by a psychological unraveling. Groff vividly portrays the effects of starvation, illness, and isolation, which lead the protagonist to experience hallucinations, visions, and disjointed dreams.

These psychological episodes are not merely signs of her deteriorating condition; they serve as a narrative device that reveals the depth of her trauma. Her memories of sexual abuse, dehumanization, and violence emerge in stark relief.

The blurring of past and present highlights how trauma is inescapable, even in the wilderness. Her hallucinations of the Dutch glassblower and the imaginary French savior offer fleeting moments of comfort and distraction.

These hallucinations underscore the human tendency to seek escapism when faced with unbearable reality. These visions represent her desire for companionship and stability but also reveal how her mind attempts to cope with the overwhelming uncertainty of her situation.

As her physical state worsens, the line between reality and illusion becomes increasingly tenuous. Groff masterfully portrays the disintegration of the self under extreme duress.

The Rejection of God and the Crisis of Faith Amidst Suffering

Faith and the rejection of God are central themes that evolve throughout the novel. The girl’s faith in God sustains her during her initial trials in the wilderness, as she repeatedly asks for deliverance and interprets her survival as proof of divine intervention.

Yet, as her suffering intensifies, she begins to feel abandoned by the very faith that once gave her strength. Her eventual rejection of God is a profound moment that marks a turning point in her psychological and spiritual journey.

The novel grapples with the question of divine justice: Why does God allow suffering, and is faith justified in the face of overwhelming misery? The girl’s struggle with these questions is not unique to her but reflective of broader existential debates.

Her final crisis of faith, in which she acknowledges the absence of God’s deliverance, leads her to a form of spiritual liberation. She no longer relies on divine intervention for survival or salvation but instead embraces the beauty and terror of the natural world on its own terms.

This shift marks her growth from a state of spiritual dependence to one of existential acceptance, though it comes at the cost of her life.

Nature as Both an Antagonist and a Source of Sublime Beauty

The wilderness in The Vaster Wilds serves as a dual force: it is both an antagonist that threatens the protagonist’s survival and a source of sublime beauty that offers moments of transcendence. Groff’s depiction of nature is intricate and ambivalent; it is neither entirely hostile nor entirely benevolent.

The girl’s relationship with the natural world is complex, as she both fears and marvels at it. Nature provides sustenance, but at a great cost—each meal is hard-won, and the line between life and death is razor-thin.

The storms, the predators, the cold—all are reminders of nature’s indifference to human survival. Yet, even in her most desperate moments, the girl finds solace in the beauty of her surroundings.

Her delight in the patterns of light, the texture of moss, and the sounds of animals reveals a deep connection to the natural world that transcends her immediate struggles. In this way, nature becomes a mirror for the protagonist’s internal state: it is vast, unknowable, and indifferent, yet also capable of moments of profound grace.

The Inevitable Collision of Mortality and Transcendence

The novel’s climax, in which the protagonist succumbs to smallpox and dies, brings together the themes of mortality and transcendence in a strikingly symbolic manner. Her death is not a violent one, nor is it caused by the wilderness itself, but by the disease brought over by the colonists.

This moment underscores the idea that, despite all of her struggles and her perseverance, the girl cannot escape the broader consequences of colonialism. Her final vision, in which she imagines an alternate life of solitude and harmony with nature, reveals her ultimate understanding that a life devoid of human companionship is incomplete.

The oak tree that grows through her ribcage after her death is a potent symbol of regeneration, continuity, and the merging of human life with the natural world. It suggests that, even in death, there is a form of transcendence.

Her body nourishes the earth and becomes part of the larger ecosystem. This final image reinforces the novel’s exploration of the porous boundary between life and death, survival and surrender, and the eternal cycle of nature’s reclamation of all things.