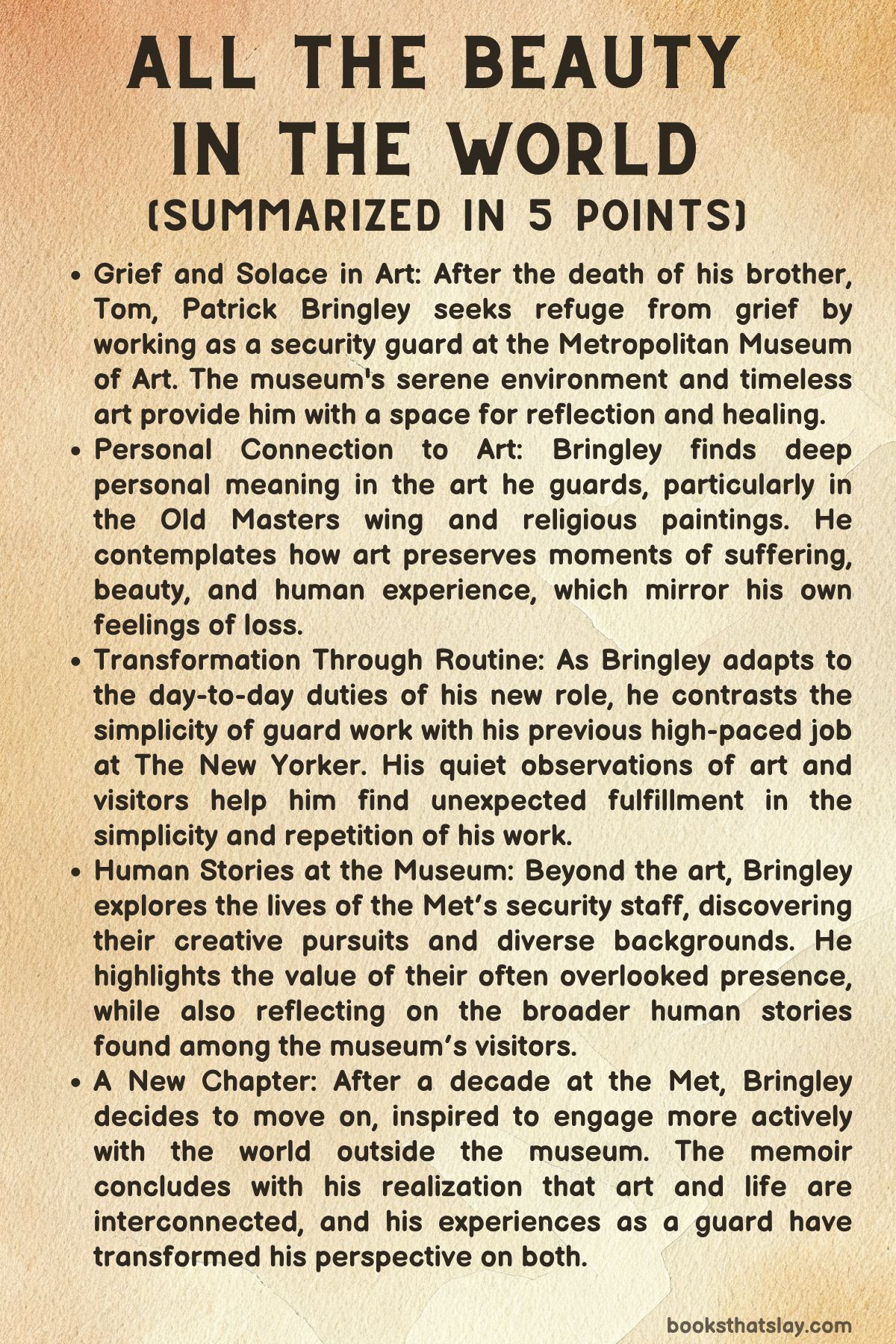

All the Beauty in the World Summary, Analysis and Themes

All the Beauty in the World: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Me is a memoir by Patrick Bringley, published in 2023. The book offers a rare, behind-the-scenes look at one of the world’s most famous museums, where Bringley spent a decade working as a security guard.

After the death of his brother, Bringley leaves his corporate job at The New Yorker to find solace among timeless artworks. His reflections touch on grief, the power of art, and the humanity he observes in both museum visitors and his fellow guards. Through Bringley’s eyes, readers gain a deeper understanding of how art shapes life.

Summary

In All the Beauty in the World, Patrick Bringley opens with his first day at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, navigating the maze-like structure under the guidance of Aada, a seasoned security guard.

As he becomes acquainted with the museum’s layout and protocols, Bringley muses on his long-standing relationship with art, dating back to his childhood museum visits and studies.

The narrative then reveals a more personal motivation for his new career: the devastating loss of his brother, Tom, whose death from cancer left Bringley seeking peace and meaning within the museum’s tranquil walls.

In the Old Masters wing, Bringley begins to connect with the timelessness of the art that surrounds him. He reflects on the profound resonance between these works and his memories of Tom, contemplating how art can freeze fleeting moments in time.

Religious paintings serve as a focal point for broader discussions of suffering, life, and death, echoing the universal human experiences Bringley has endured.

The memoir then delves into Bringley’s bond with Tom, offering a deeper glimpse into his brother’s life and untimely passing at 26.

The sorrowful recounting of their visit to the Philadelphia Museum of Art after Tom’s diagnosis adds emotional weight, as it is in that moment Bringley finds solace in Renaissance art and decides to work at the Met.

As Bringley settles into his routine at the museum, he contrasts the immersive calm of his new role with the fast-paced intensity of his former job at The New Yorker.

His time in the Egyptian wing, in particular, triggers philosophical reflections on the passage of time and humanity’s enduring connection to the past. He also begins to see the value of quiet observation, both of the art and the visitors.

Bringley’s perspective deepens as he interacts with diverse art forms—from Monet’s impressionism to ancient Chinese scrolls—developing a unique approach to viewing and understanding art.

He is fascinated by the global stories each piece tells and how it all comes together to form the Met’s vast collection. He also starts to see how the Met itself operates, not just through its curators but through the lives of the guards, who bring their own artistic and creative backgrounds to their work.

One significant event is the Picasso exhibition, where Bringley ponders the role of museum guards—figures who blend into the background yet witness a vast array of human interactions with art.

He begins to appreciate the visitors as much as the exhibits, shifting his understanding of both art and humanity.

This shift continues as his personal life intertwines with his professional one, particularly through his relationship with Tara, his eventual wife, and their visits to other museums, where art becomes a backdrop for love and loss.

As the memoir progresses, Bringley observes more than just artworks—he sees the stories of the security guards who protect them.

These guards come from diverse backgrounds, and their artistic endeavors outside of the museum offer a glimpse into how people find their own forms of creative expression.

By the book’s end, Bringley reflects on his time at the Met and his decision to leave, feeling ready to step beyond the museum’s walls.

His decade-long journey has not only deepened his appreciation for art but also reshaped his view of life, offering him new avenues for growth.

Analysis and Themes

The Intersection of Art and Human Suffering: The Duality of Preservation and Pain in Bringley’s Memoir

In All the Beauty in the World: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Me, Patrick Bringley explores how art becomes a repository for human suffering and resilience. He intricately weaves the theme of loss into his personal journey and his encounters with the Met’s collections.

His brother Tom’s death from cancer looms as a profound catalyst for his career shift. It drives him to seek solace within the walls of the museum.

This experience is juxtaposed with Bringley’s reflections on religious art, particularly the Old Masters. Here, depictions of suffering, redemption, and transcendence become mirrors to his grief.

Through these parallels, Bringley constructs a narrative in which the preservation of art is not merely an act of cultural significance, but a testament to humanity’s ability to endure tragedy. His work as a security guard becomes symbolic of a deeper effort to guard not only the art itself but the emotional histories embedded within it.

This duality between art as eternal preservation and the ephemeral nature of human suffering pervades the memoir. Bringley contemplates how art provides both a refuge from and a reflection of life’s deepest pains.

The Temporal Continuum of Human Experience as Reflected in Art: Contrasting Cyclical and Linear Perceptions of Time

Bringley’s memoir delves deeply into the philosophical dimensions of time, particularly through the lens of the Metropolitan Museum’s collection. His reflections in the Egyptian wing contrast the cyclical understanding of time held by ancient Egyptians with modern society’s more linear perception.

In this context, Bringley’s work as a security guard becomes not merely about safeguarding static objects. Rather, it is about engaging with a temporal continuum that connects past, present, and future.

The art he observes, from ancient artifacts to modern masterpieces, represents both moments frozen in time and ongoing narratives of human existence. These temporal reflections are personal for Bringley as well, as he grapples with the cyclical nature of loss and renewal following his brother’s death.

By juxtaposing ancient conceptions of eternity with his own experiences of fleeting human life, Bringley situates himself within a broader framework of time’s passage. He explores art’s endurance and life’s inevitable finitude.

Art as a Mechanism for Processing Grief and Building New Identities in the Wake of Loss

The memoir is suffused with Bringley’s exploration of art as a means of processing grief. Art also helps in constructing new personal identities.

His transition from a promising career at The New Yorker to the understated role of a security guard at the Met reflects a desire to retreat from the frenetic pace of modern life. He seeks meaning in stillness and finds it in art.

The role of art becomes therapeutic and meditative, offering him emotional refuge and a space to reconfigure his sense of self. This self-reconstruction follows the traumatic loss of his brother.

Bringley’s interactions with various works of art, from Renaissance masterpieces to African artifacts, offer insights into different modes of resilience and recovery. His personal journey mirrors the transformations art undergoes, suggesting that in grief, one must similarly reconstruct one’s sense of self.

Through these experiences, Bringley constructs an identity rooted not in professional success but in a contemplative appreciation of beauty, endurance, and personal meaning.

The Role of Art in Bridging Personal and Collective Histories: The Complexities of Curating Human Experience

One of the most intellectually complex themes Bringley navigates in his memoir is the intersection of personal memory and collective history. This theme is mediated through the lens of art.

His experiences as a security guard place him in the unique position of observing art as both an individual seeking solace and part of a larger institutional narrative. This dual role complicates Bringley’s engagement with the artworks, as he reconciles his personal emotional responses with broader, often politicized histories.

His reflections on African artifacts evoke questions about ownership and interpretation, especially in light of colonial legacies. The act of curating a museum becomes a metaphor for how societies choose to remember—or forget—their pasts.

Just as individuals curate their own personal histories, institutions curate the past. Bringley’s memoir thus becomes an exploration of how art serves as a bridge between individual and collective memory, personal trauma, and cultural history.

The Dialectic of Observation and Participation: The Museum Guard as Both Detached Observer and Engaged Participant

In Bringley’s memoir, the museum guard symbolizes a unique dialectic between observation and participation. His role as a security guard forces him into a liminal space, where he is both part of the museum’s ecosystem and apart from it.

He facilitates the public’s interaction with art while remaining a passive observer himself. Over time, Bringley begins to question this detachment, especially as he reflects on the visitors he encounters.

He becomes aware that he is not merely guarding static works of art but engaging with dynamic human experiences. His observations of museum visitors lead him to rethink his own role within this system.

This realization culminates in his decision to leave his position and pursue a career as a tour guide. His transition symbolizes his desire to move from passive observation to active participation in the art world and life more broadly.

This theme underscores the tension between the passive consumption of beauty and the active creation of meaning. This tension is relevant both in the realm of art and in the wider human experience.

The Inevitability of Imperfection: Navigating the Unfinished Nature of Art and Life

Bringley’s reflections on the Michelangelo and Gee’s Bend quilt exhibitions in Chapter 12 serve as a profound meditation on imperfection. The unfinished nature of both art and life becomes a central metaphor.

Michelangelo’s unfinished works and the Gee’s Bend quilts reveal deeper truths about the human condition. Both artistic endeavors reflect interruptions, struggles, and moments of incompletion that mirror life itself.

This theme resonates with Bringley’s own life as he navigates the unfinished business of grief, parenthood, and self-discovery. The concept of the “unfinished” becomes a metaphor for the ongoing, imperfect process of living.

Bringley finds beauty not in perfect resolutions but in the resilience and act of creation. His memoir transcends a recounting of his time at the Met, becoming a reflection on the larger, unfinished nature of all human endeavors.