We Must Not Think of Ourselves Summary, Characters and Themes

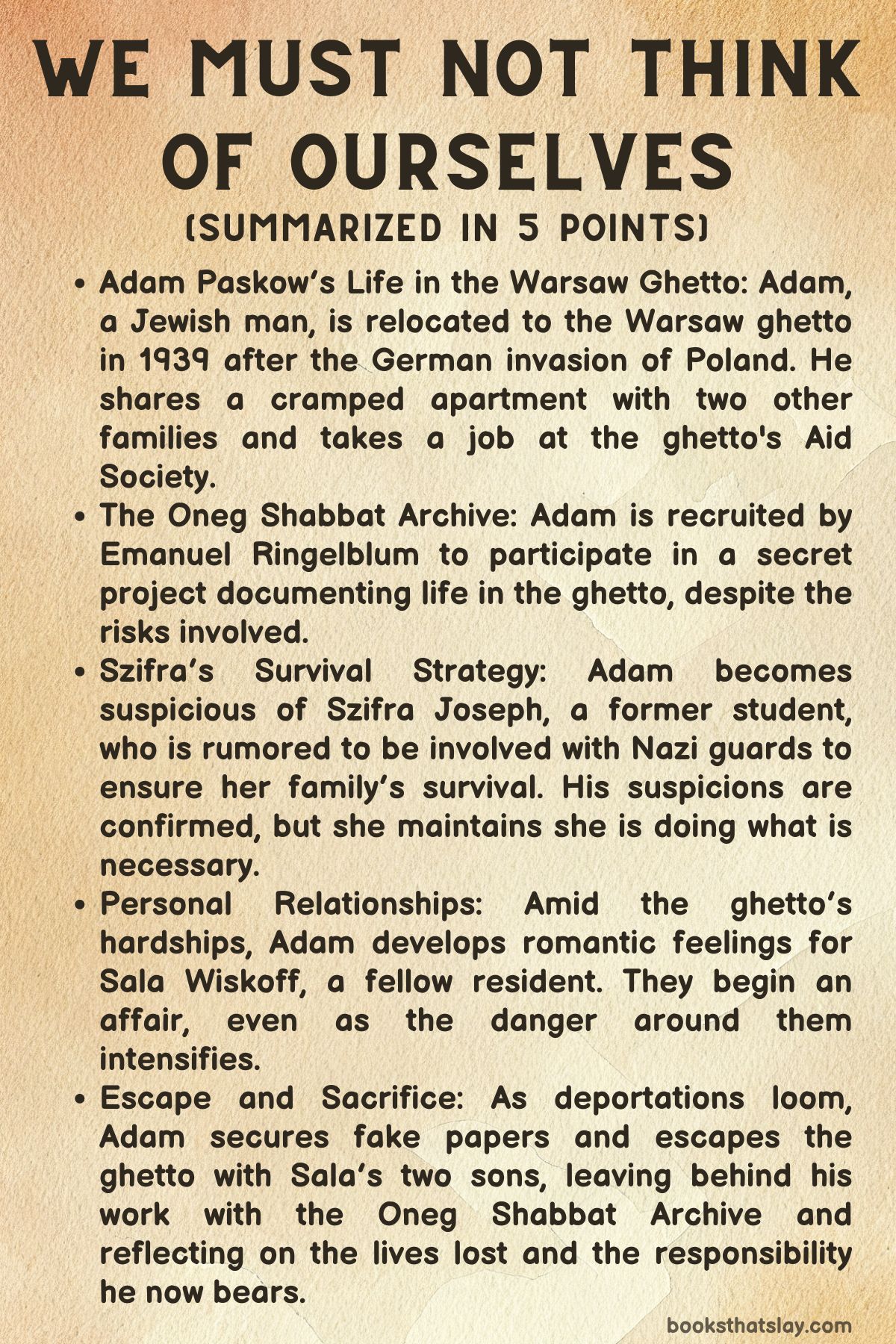

We Must Not Think of Ourselves by Lauren Grodstein is a historical novel set during World War II, capturing the harrowing experiences of life in the Warsaw ghetto. The story follows Adam Paskow, a Jewish man who participates in a secret project led by Emanuel Ringelblum to document the lives of Jewish residents trapped in the ghetto.

As Adam navigates his own grief and the crumbling world around him, he faces unimaginable choices, explores complex relationships, and confronts the moral and emotional turmoil of survival. This novel vividly captures the resilience of the human spirit amidst unimaginable darkness.

Summary

The story is told from the perspective of Adam Paskow, a Jewish man relocated to the Warsaw ghetto in 1939 after the German invasion of Poland. Before the war, Adam had been married to Kasia, a Catholic woman who tragically passed away from a brain injury.

Her influential father, Henryk Duda, arranges for Adam to secure a somewhat better place in the ghetto in exchange for the couple’s old apartment. Henryk also asks for Kasia’s wedding jewelry to help Adam flee Poland, but Adam decides to keep it as a safeguard for the future.

Upon reaching the ghetto, Adam discovers that Henryk has made empty promises: the same apartment has been offered to two other families—Emil and Sala Wiskoff, along with their two sons, and the Lescovecs, a family of five. With no other options, they are forced to share the small, cramped space.

Adam takes a job at the local Aid Society and soon reconnects with a former student, Szifra Joseph, who convinces him to start teaching English to some of the children in the ghetto.

Szifra, known for her striking appearance, is rumored to have dealings with Nazi guards, leading Adam to grow suspicious.

Adam is soon recruited by Emanuel Ringelblum to join the Oneg Shabbat Archive, a dangerous but vital project to document life in the ghetto.

As Adam conducts interviews and observes the daily struggles of the community, tensions rise in the ghetto.

One day, his suspicions about Szifra are confirmed when he accidentally sees her involved with a Nazi officer.

Despite this, Szifra insists that she is only doing what is necessary to provide for her family, particularly her two younger brothers. Soon after, her mother dies from illness, leaving Szifra as the sole caretaker of her siblings.

Life in the ghetto becomes more desperate as people struggle for survival. Smuggling becomes a lifeline, though it is fraught with danger, as demonstrated when one of the Lescovec boys is killed during a smuggling attempt.

In the midst of this chaos, Adam develops a romantic relationship with Sala Wiskoff, though their affair is fraught with guilt and secrecy.

As deportations and violence intensify, Henryk’s offer to smuggle Adam out of Poland resurfaces.

Though wary, Adam gives Henryk Kasia’s necklace in exchange for papers. However, he learns too late that Henryk has been killed for double-crossing both the Nazis and the Polish resistance.

With no other choice, Adam turns to a Polish guard named Nowak, giving him the necklace to secure his escape.

Before fleeing, Adam finds Szifra’s lifeless body in his classroom, along with identification papers meant for her brothers. Knowing that the Wiskoff boys’ survival is now his responsibility, Adam replaces the brothers’ photos with those of Sala’s sons.

Finally, Adam secures passage out of the ghetto, taking Sala’s children with him, leaving behind his work with the Oneg Shabbat Archive, and reflecting on the weight of responsibility for the lives now entrusted to him.

Characters

Adam Paskow

Adam Paskow is the novel’s central character and the first-person narrator, through whose perspective we witness the tragedies of the Warsaw ghetto. A Polish Jew, Adam is an emotionally complex figure who has endured the loss of his wife, Kasia, before the invasion.

This tragedy haunts him as he navigates the brutal and claustrophobic conditions of the ghetto. Adam’s sense of loss and isolation becomes even more pronounced as he is forced to give up his home and his memories of Kasia, trading them for a place in the ghetto and, later, for the promise of escape.

Adam is not a hero in the traditional sense, but a deeply human character—cynical, pragmatic, and at times morally ambiguous. His participation in Emanuel Ringelblum’s Oneg Shabbat Archive gives him a sense of purpose, a way to resist the dehumanization around him by recording the lives of his people.

Adam’s emotional arc moves through grief, duty, and love, especially as he grows close to Sala, leading to his eventual acceptance of responsibility for her children. Despite his feelings of love for Sala, Adam’s final act of escape with her children is not one of personal triumph but rather a survival borne of guilt and desperation.

Kasia Duda

Although Kasia is dead at the start of the novel, her presence and memory significantly influence Adam’s actions. A Polish Catholic woman, Kasia represents the world Adam lost, a life outside the ghetto.

The fact that Adam holds on to her wedding jewelry as a “safety net” signifies not only his attachment to her memory but also his struggle to reconcile his current reality with the happier life he once knew. Kasia’s death marks the beginning of Adam’s slow descent into the harsh realities of the war, and her absence drives his interactions with other characters, particularly her father, Henryk.

Her memory creates a subtle tension between Adam’s Jewish identity and his marriage to a Catholic woman, which has distanced him from both Polish society and his fellow Jews.

Henryk Duda

Henryk, Kasia’s father, is a wealthy, well-connected Polish man who initially offers Adam some protection by securing him a place in the Warsaw ghetto. However, his character is marked by selfishness and betrayal.

He demands Kasia’s jewelry from Adam in exchange for papers that could help Adam escape the ghetto. Henryk is a morally ambiguous figure, someone who represents the compromises and corruption that many faced in order to survive.

His eventual downfall, being caught double-dealing between the Nazis and the Polish Army, signals the limits of his power and influence, as well as the inevitable collapse of those who try to manipulate both sides of the war for personal gain.

Emanuel Ringelblum

Emanuel Ringelblum is a historical figure and the driving force behind the Oneg Shabbat Archive project. In the novel, he recruits Adam to join his efforts in documenting the lives of Jews in the Warsaw ghetto, a project that represents a form of intellectual and spiritual resistance against the Nazis.

Ringelblum is portrayed as a determined and principled man, committed to preserving the truth about the Jewish community under siege. His dedication to the archive serves as a contrast to Adam’s growing cynicism and is a reminder of the collective responsibility the ghetto’s inhabitants bear toward each other.

Ringelblum’s influence on Adam underscores the importance of memory and testimony, even in the face of overwhelming despair and destruction.

Szifra Joseph

Szifra is one of Adam’s former students and a young woman who becomes emblematic of the moral compromises individuals were forced to make under Nazi occupation. She initially appears to be a dedicated student, but as rumors of her fraternizing with Nazi guards spread, her character takes on a more tragic and complex dimension.

Szifra’s involvement with the Nazi guards, trading sex for food and protection, reflects the dire choices available to those trying to survive in the ghetto. Her final request to Adam—to teach her how to say “I am a virgin” in German—highlights her vulnerability and the desperation she feels in trying to protect her family.

Szifra’s murder is a devastating moment, not only because of the violence she endures but also because her death signals the ultimate failure of her efforts to escape the ghetto with her brothers. Adam’s discovery of the Polish kennkartes in her pocket symbolizes both the lost hope for her future and the harsh realities of survival.

Sala Wiskoff

Sala is the wife of Emil Wiskoff and becomes Adam’s love interest over the course of the novel. Her character represents resilience and pragmatism in the face of unbearable hardship.

Sharing the cramped apartment with Adam and her family, Sala endures the loss of her fellow tenants, her dwindling resources, and the constant fear of deportation. Her relationship with Adam grows out of shared suffering and proximity, though her primary concern remains her two sons.

Sala’s affair with Adam is not born of pure romantic passion but from a desperate need for comfort and human connection in the dehumanizing environment of the ghetto. Her willingness to let Adam take her sons to safety, even though it means staying behind herself, showcases her maternal sacrifice and underscores her emotional complexity as a character caught between love, duty, and survival.

Emil Wiskoff

Emil is Sala’s husband and the father of their two sons, yet he remains a somewhat passive figure in the novel, overshadowed by the more active roles of Adam and Sala. Emil’s emotional and physical deterioration as the ghetto’s conditions worsen reflects the broader collapse of families and social structures under Nazi oppression.

His inability to protect his family or improve their situation contrasts with Adam’s growing role as a protector for Sala and her children. Emil’s presence serves as a reminder of the countless men in the ghetto who, stripped of their roles as providers and protectors, succumbed to the overwhelming forces of starvation, disease, and despair.

Nowak

Nowak is a Polish guard who smuggles goods into the ghetto in exchange for valuable items, serving as a link between the ghetto inhabitants and the outside world. His role in the story represents the morally gray area of collaboration and exploitation.

Although he is helping Adam by facilitating his escape, Nowak’s motivations are purely mercenary. He does not care about Adam’s survival beyond what he can extract in return for his services.

His character underscores the transactional nature of survival in the ghetto, where even the most intimate human relationships are reduced to bargaining and exchange.

Themes

The Moral Weight of Witnessing

A central theme of the novel is the profound moral responsibility that comes with witnessing suffering during historical catastrophe. Through the lens of Adam Paskow’s writings, the story presents the act of documentation not as passive record-keeping but as a sacred moral imperative.

Adam is recruited into the Oneg Shabbat archive to record everyday life within the Warsaw Ghetto, and while this seems at first like an intellectual task, it becomes a spiritual and existential burden. As deportations escalate and the people around him—his students, lovers, and neighbors—vanish or perish, Adam increasingly questions whether recording is enough.

He fears that chronicling suffering without acting against it could be an act of complicity. Yet the novel makes clear that preserving the memory of a people marked for erasure is itself a form of resistance.

The act of writing down the stories of the oppressed, especially when done with care and honesty, is one of the few tools available to preserve dignity against a regime that seeks to annihilate not just lives but entire histories. This theme resonates through Adam’s final reflections, where he expresses the desperate hope that someone, someday, will read his account and remember.

His notebook, later recovered after the war, becomes a monument to the lives erased—testimony that insists the victims of the Holocaust be seen and known, not abstracted into anonymous statistics. In this sense, the novel presents writing not just as remembrance but as a plea against silence and forgetting.

Survival and the Erosion of Ethics

Throughout the novel, survival emerges as a brutal, destabilizing force that tests and often erodes ethical boundaries. In the Warsaw Ghetto, where life is reduced to hunger, cold, and the constant threat of deportation, moral certainties dissolve under the pressure of daily desperation.

Characters like Szifra Joseph embody this dilemma most sharply. Her determination to survive, even if it means pretending to be Aryan, seducing soldiers, or abandoning communal norms, positions her in contrast with Adam’s more restrained moral code.

Yet the novel refuses to judge her. Instead, it presents survival as a force that compels individuals to make impossible choices—choices shaped by fear, resource scarcity, and the sheer randomness of who lives and who dies.

Even Adam, who begins with the idealism of an educator and chronicler, finds his values shifting as his loved ones disappear. He accepts Henryk Duda’s dubious favors, watches his students steal food, and ultimately questions his own inaction.

These moments suggest that in extreme situations, the distinction between right and wrong becomes blurred, not out of corruption but necessity. The novel doesn’t excuse moral compromise, but it humanizes it, portraying survival as a grim, sometimes shameful endeavor.

By the end, nearly every character has crossed some internal line to stay alive—or died trying not to. This moral ambiguity reinforces the tragic reality of life in the ghetto, where ethical behavior often leads not to salvation, but to suffering or death.

The Collapse of Normalcy and the Illusion of Order

Another significant theme is the slow collapse of normal life and the psychological effort to preserve illusions of order in the face of overwhelming chaos. The ghetto is a place where everyday routines continue—children attend poetry lessons, families argue over shared meals, neighbors squabble—yet this semblance of normalcy is constantly undercut by the brutality outside the walls.

One poignant example is Adam’s documentation of a family that still dresses for dinner, setting the table with broken china as if performing a play for an audience that no longer exists. This desperate adherence to routine underscores a human need for control, for the comfort of the familiar, even when it is clear that life is no longer governed by logic or fairness.

For the characters, performing these rituals becomes an act of resistance—not just against the Nazis, but against despair. However, the novel also exposes the futility of such efforts.

As the deportations escalate and neighbors vanish overnight, the routines crumble. Children like Filip, Charlotte, and Roman are slowly stripped of innocence.

The ghetto walls shrink not just the physical world but also the mental space in which hope can exist. Even Sala Wiskoff, initially skeptical of false optimism, eventually clings to the idea of volunteering for a work detail as a path to survival, knowing it might be a lie.

The novel powerfully illustrates how the illusion of order becomes both a survival mechanism and a tragedy in itself. It reveals the human tendency to find structure in the face of the unimaginable.

Love, Intimacy, and Human Connection Amid Horror

In the bleak landscape of the ghetto, moments of intimacy offer fleeting but vital glimpses of humanity. The romantic connection between Adam and Sala becomes a quiet rebellion against the dehumanizing conditions around them.

Their relationship is not grand or romanticized. It is awkward, secretive, and weighed down by fear.

Yet it represents a space where two people can see each other as more than statistics or victims. This theme of connection is not limited to romantic love.

Adam’s care for his students, especially the vulnerable ones like Filip and Charlotte, shows the importance of emotional bonds in resisting emotional numbness. Even small acts—like sharing poetry, offering gumballs, or holding a child’s hand during a raid—carry immense weight.

These moments remind readers that tenderness persists even when the world is collapsing. However, the novel also acknowledges the fragility of these bonds.

Sala disappears, Filip dies, and Adam is left with only memories and regrets. The pain of loss becomes entwined with the comfort those relationships once provided.

In this way, the novel does not offer love as a solution or salvation, but as a temporary shelter—a reason to care, to write, to mourn. These connections are what make Adam’s record more than a diary; they make it a requiem.

Through this lens, the novel argues that human connection is what gives suffering its meaning and testimony its urgency.