Ghosts of Honolulu Summary and Analysis

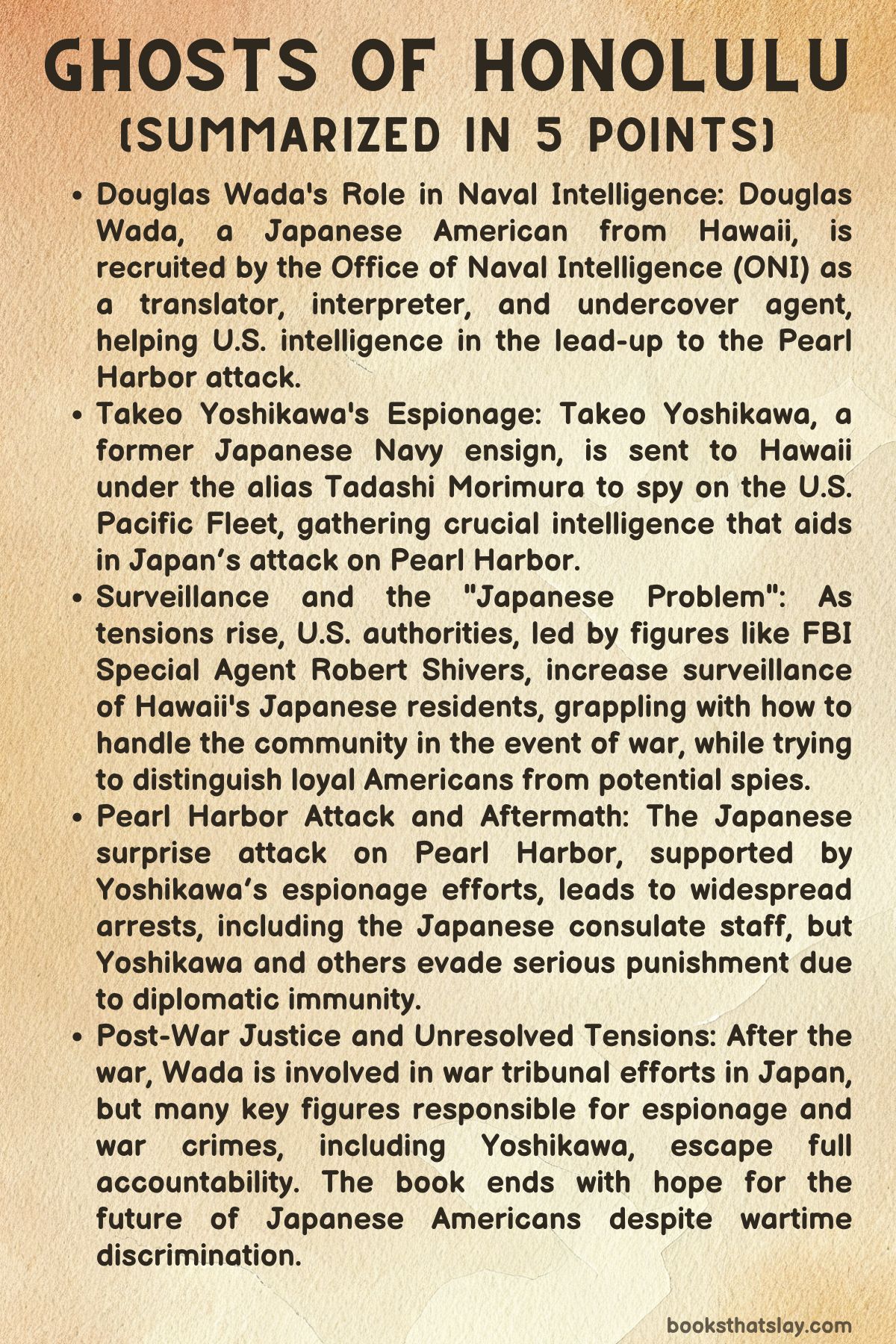

Ghosts of Honolulu is a book by Mark Harmon and Leon Carroll Jr. that talks about the hidden stories of espionage leading up to the attack on Pearl Harbor.

The book centers on lesser-known figures within the world of intelligence, focusing on a Japanese spy sent to monitor U.S. military operations in Hawaii and a Japanese American who works in Naval Intelligence. It paints a gripping picture of the moral complexities faced by Japanese Americans during World War II, as well as the community’s patriotic contributions, despite the suspicion and discrimination many endured.

Summary

Douglas Wada, an American of Japanese ancestry, is raised in Hawaii by Issei parents and grows up deeply connected to his cultural roots. After attending McKinley High, a predominantly Japanese school, Wada’s immersion in American culture leads his parents to send him to Japan in fear that he’s losing touch with his heritage.

Wada spends five years in Japan before returning to Hawaii just as tensions between the U.S. and Japan rise, having renounced his Japanese citizenship to avoid conscription. Back home, he attends the University of Hawaii, where he meets Ken Ringle, a Navy officer seeking trusted Japanese Americans for the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI).

After extensive background checks, Wada is recruited into Naval Intelligence as an interpreter, translator, and, on occasion, an undercover agent. Meanwhile, Takeo Yoshikawa, a former Japanese Navy ensign disillusioned with his career, is recruited by Japan’s intelligence service to spy on the U.S. Pacific Fleet.

As war looms, Wada and his colleagues in Hawaii face growing concerns about the Japanese community, especially with the presence of spies within the Japanese consulate.

The FBI, led by Special Agent Robert Shivers, intensifies its surveillance of Japanese residents and begins compiling lists of potential detainees. Although many within the military push for mass arrests, Ringle argues that most Japanese Americans in Hawaii are loyal to the U.S. Wada settles into family life in Hawaii, but U.S. intelligence knows that the Japanese consulate is a hub of espionage activity.

While American intelligence increases its monitoring of Japanese diplomats and civilians, Yoshikawa arrives in Hawaii under the guise of a Japanese consulate staff member named Tadashi Morimura.

He meticulously tracks U.S. naval activities, photographing and reporting on fleet movements. His covert efforts, aided by local Japanese American drivers, provide vital intelligence for Japan’s planned attack on Pearl Harbor. As the attack approaches, U.S. officials begin intercepting signs of imminent war, but critical warnings fail to reach Pearl Harbor in time.

On December 7, 1941, Japan launches its surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. Yoshikawa’s espionage directly contributes to the devastation, but his cover as a consulate staff member holds up for a time.

Following the attack, the consulate is raided, and Yoshikawa is arrested, though he remains largely unscathed due to diplomatic immunity. As the U.S. declares war on Japan, widespread suspicion falls on Japanese Americans, leading to the mass detention of Japanese communities on the West Coast, though Hawaii’s Japanese population remains less affected.

In the aftermath, Wada aids the U.S. war effort by interrogating Japanese prisoners and participating in the war tribunal efforts in post-war Japan. Despite attempts to bring key figures like Yoshikawa to justice, most evade punishment.

The book concludes with Wada’s father, hopeful for the future of their family in Hawaii despite the hardships they endured during the war.

Characters

Douglas Wada

Douglas Wada is one of the central characters in Ghosts of Honolulu, and his journey reflects the tension of identity faced by many Japanese Americans during World War II. Born to traditional Issei (first-generation Japanese immigrant) parents in Hawaii, Wada represents the duality of being both American and Japanese.

His upbringing in Hawaii’s predominantly Japanese community exposes him to American culture, which he embraces, especially in his love for baseball and cars. However, his parents’ concerns about him losing touch with his Japanese heritage lead them to send him to Japan.

This period of his life in Japan deepens his understanding of both cultures, but also heightens his anxieties about war, forcing him to flee back to Hawaii. Wada’s recruitment into the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) positions him as a bridge between two worlds.

As a trusted interpreter and sometimes undercover spy, Wada serves the American government while navigating the suspicion and scrutiny that came with being of Japanese descent in the prelude to war. His loyalty to America is unquestionable, but his work places him in the uncomfortable position of monitoring his own community, which is under suspicion from US intelligence.

His marriage and growing family further complicate his personal stakes as he becomes more deeply involved in the US war effort. Despite these challenges, Wada’s journey is one of perseverance and moral complexity, as he strives to prove the loyalty of Japanese Americans while aiding in the war against Japan.

Takeo Yoshikawa

Takeo Yoshikawa is the Japanese spy tasked with monitoring the US Naval Fleet in Hawaii. A disgruntled former ensign in the Imperial Japanese Navy, Yoshikawa’s motivations stem from a deep sense of dissatisfaction and nationalism.

His character contrasts sharply with Wada, as Yoshikawa fully embraces his role in the Japanese war effort, meticulously preparing for his mission over several years. He learns English, studies US Navy ships, and adopts a new identity, “Tadashi Morimura,” to blend in while conducting surveillance on the Pacific Fleet.

Yoshikawa is portrayed as cunning and determined, successfully operating as a spy under the cover of being a consular staff member in Hawaii. His actions directly contribute to the success of the Pearl Harbor attack, making him one of the key agents behind the assault.

Despite the pivotal role he plays, Yoshikawa’s eventual fate is somewhat anticlimactic; he is arrested and deported in a spy exchange, avoiding punishment for his involvement in the attack and subsequent war crimes. His survival and evasion of consequences underscore the complexities of wartime justice, particularly in the context of espionage and international diplomacy.

Ken Ringle

Ken Ringle, a Navy commander and Wada’s older classmate, plays a significant role in shaping the intelligence operations in Hawaii and later on the West Coast. He is portrayed as a level-headed, pragmatic officer who understands the potential of Japanese Americans to contribute to the war effort, rather than viewing them solely as a threat.

His recruitment of Wada into the ONI signals his trust in Japanese Americans, despite the growing paranoia surrounding their loyalties. Ringle’s advocacy for Japanese Americans, particularly in his attempts to demonstrate their loyalty to the US military, sets him apart from many of his contemporaries who were eager to view them as fifth columnists.

When Ringle is reassigned to California, his role in tackling the “Japanese Problem” becomes even more critical. He works to prevent the wholesale incarceration of Japanese Americans.

His leadership and reasoned approach contrast with the more extreme voices calling for the mass detention of the entire Japanese population. Ringle’s efforts reflect the internal divisions within US intelligence and the government regarding the treatment of Japanese Americans during the war.

Robert Shivers

Robert Shivers, the FBI Special Agent in Charge in Hawaii, is another significant figure in the story. He represents the more hawkish side of US intelligence, advocating for aggressive measures against Japanese residents and consulate staff.

Shivers’ role in setting up a field office to monitor the Japanese population and create detention lists reveals the level of suspicion and paranoia that permeated the intelligence community in the lead-up to the Pearl Harbor attack. His attempts to have the entire Japanese consulate staff arrested, which are ultimately denied by the Roosevelt administration, demonstrate the lengths to which he is willing to go to mitigate perceived threats.

Shivers is a key figure in the surveillance and monitoring efforts against the Japanese consulate. This leads to the eventual arrests following the attack on Pearl Harbor.

His efforts, however, are not without moral ambiguity, as they raise questions about civil liberties and the treatment of Japanese Americans during the war.

Gero Iwai

Gero Iwai, like Wada, is a Japanese American working within the intelligence community. As an officer in the Army Corps of Intelligence Police (CIP), Iwai represents another example of Japanese Americans serving their country during a time when their loyalty was under suspicion.

His role in monitoring the Japanese population and participating in intelligence efforts highlights the internal conflicts faced by Japanese Americans who were asked to surveil their own communities. Iwai’s collaboration with Wada in interrogating a captured Japanese submariner following the attack on Pearl Harbor underscores the importance of their work.

Yet, his character also reflects the broader theme of the often unrecognized contributions of Japanese Americans during the war.

Nagar Kita

Nagar Kita, the Japanese consul general in Hawaii, is the handler for Takeo Yoshikawa and plays a key role in facilitating espionage efforts leading up to the Pearl Harbor attack. His character is emblematic of Japan’s covert operations and the strategic planning that went into the surprise assault.

As a high-ranking diplomat, Kita is able to provide Yoshikawa with cover, allowing him to operate freely in Hawaii. His involvement in the spy network highlights the diplomatic manipulation that accompanied Japan’s military ambitions.

Otto Kuehn

Otto Kuehn, a Nazi spy recruited by Yoshikawa, adds another layer of intrigue to the story. His role in assisting the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, despite being a German national, showcases the complex web of alliances and espionage that defined Axis collaboration during World War II.

Kuehn’s involvement further demonstrates the global scale of intelligence operations during the war. It also highlights the shared goals of Axis powers in undermining the Allied forces.

Masai Marumoto

Masai Marumoto, a respected attorney in Hawaii, is instrumental in rallying Nisei (American-born Japanese) support for the US war effort. His character represents the internal conflict within the Japanese American community, many of whom felt the pressure to prove their loyalty to America in the face of widespread suspicion.

Marumoto’s efforts to mobilize the Nisei reflect the broader theme of Japanese American patriotism and the desire to demonstrate their allegiance. This occurred even as they faced discrimination and the threat of internment.

Analysis and Themes

Dual Identity and Cultural Displacement

The theme of dual identity is central to the life of Douglas Wada and forms one of the emotional and philosophical backbones of the book. Born in Hawaii to Japanese immigrant parents, Wada is pulled between two worlds: the traditions of his heritage and the American identity he is growing into.

His early years reflect this push and pull, as his parents strive to instill traditional values, language, and Shinto beliefs while he is also immersed in American education, sports, and ideals. The cultural displacement intensifies when his parents send him to Japan under the pretense of a coronation trip, only for him to be immersed in a rigid, militarized educational system.

He becomes both an insider and outsider in Kyoto, recognized for his Japanese ancestry but treated as American due to his mannerisms and worldview. His return to Hawaii does not resolve this conflict.

Instead, it complicates it further. Now with a deeper understanding of Japanese nationalism and culture, Wada must integrate back into an American society that becomes increasingly suspicious of people who look like him.

His language skills and insider knowledge make him valuable to Naval Intelligence, but they also isolate him from both the white-dominated military structures and the Japanese American community. His recruitment into ONI forces him to navigate this cultural limbo daily—asked to spy on institutions he once belonged to, while never fully trusted by those he serves.

This complex interplay between belonging and alienation showcases the psychological cost of dual identity. The book does not offer easy resolutions but illustrates how Wada’s internal conflict is both a burden and a unique strength.

His life becomes a living embodiment of the broader struggle faced by many Nisei during the war, forced to prove loyalty to a country that viewed them with suspicion.

Espionage, Trust, and the Failure of Intelligence

Throughout the narrative, espionage and intelligence work are depicted not as glamorous, clear-cut endeavors but as murky, often morally ambiguous undertakings. The intelligence community in pre-war and wartime Honolulu is characterized by paranoia, overlapping jurisdictions, and a general failure to distinguish between genuine threats and imagined ones.

The Japanese consulate, under the guise of diplomacy, becomes a hub of espionage, with figures like Takeo Yoshikawa using simple but effective observation methods to map U.S. naval movements. Despite this, American agencies often miss or misinterpret key signals.

Coded messages sent through diplomatic cables are intercepted, but not acted upon until after the Pearl Harbor attack. Wiretaps and surveillance operations yield vast amounts of trivial information, while more serious threats go undetected or ignored.

The mistrust within the intelligence community itself also plays a role in these failures. Rivalries between the Navy, Army, and FBI create bureaucratic silos, delaying the sharing of information.

Even within their own agencies, officers like Mayfield and Shivers must struggle to convince higher-ups of the need for increased coordination and urgency. This administrative inertia is most tragically illustrated in the days leading up to Pearl Harbor, when intercepted messages containing exact ship positions are not disseminated in time to prevent disaster.

On a more personal level, trust becomes a recurring issue. Figures like Douglas Wada and Gero Iwai, Japanese Americans working in U.S. intelligence, must constantly prove their loyalty, despite risking their lives and facing rejection from both the government and their own community.

Their effectiveness is often undercut by racial prejudice, showing how institutional bias can sabotage even the best efforts at security. The theme underscores that intelligence failures are not just technological or logistical—they are human, grounded in fear, pride, and ignorance.

Patriotism and Prejudice in Wartime America

The question of what it means to be patriotic is continually tested in Ghosts of Honolulu. Japanese Americans in Hawaii and on the mainland are placed under a microscope, with their actions, affiliations, and even religious practices subjected to intense scrutiny.

Patriotism, in this context, becomes a performance as much as a belief. Events like the McKinley High School rally are designed to visibly showcase Japanese American loyalty, but they also function as surveillance tools for the FBI and other agencies.

Participation in such events may earn temporary favor but does not remove systemic suspicion. For Douglas Wada, patriotism is expressed not through public demonstration but through his commitment to the difficult, thankless work of espionage.

Yet even this is not enough. Despite his critical contributions, he is frequently isolated and distrusted. His cultural knowledge makes him indispensable, but it also marks him as suspect.

Similarly, Gero Iwai navigates the Army’s counterintelligence world while trying to retain ties to the Japanese community that increasingly views him as a traitor. Their experiences highlight how the government weaponizes patriotism as a conditional status, reserved for those willing to disavow aspects of their heritage.

The larger societal response mirrors this contradiction. While Japanese American civic leaders organize loyalty drives and contribute to defense efforts, the federal government simultaneously prepares lists for mass internment.

Religious institutions, especially Shinto shrines, are closed or monitored. This double standard is never more apparent than in the case of Hisakichi Wada, who builds shrines that are later defaced or destroyed in the name of security.

The theme of patriotism, therefore, is not just about national allegiance—it becomes a crucible in which identity, loyalty, and civil rights are all tested.

Legacy, Memory, and Cultural Survival

The question of legacy weaves through the closing sections of the book, where personal and cultural survival become paramount. For Hisakichi Wada, legacy is literal—the physical shrines he crafts, the wood he carves, the community he once served.

But war erodes these foundations. His wife dies, his daughters leave, and the shrines are shuttered or demolished. His final act of carving a miniature shrine with a partially amputated hand becomes a quiet act of resistance and remembrance.

It is not just art—it is testimony. He asserts his place in a community that once pushed his faith and culture to the margins. For Douglas, legacy is less tangible.

His role in wartime intelligence, recognized only through a certificate, does not fully account for the emotional toll and cultural fragmentation he endures. His postwar work at the Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal deepens his disillusionment.

There, he is caught between the role of translator, historian, and witness. He sees firsthand the destruction of a country he once feared and the suffering of its people.

His eventual return to Hawaii and his work with civic groups represent a kind of reconciliation—an attempt to reanchor himself in community after years of dislocation. In both father and son, the book finds hope in endurance rather than triumph.

Cultural survival is not portrayed as the reestablishment of old traditions in their original form but as a slow, painful evolution. The miniature shrine in the Daijingu Temple, and Douglas’s mentoring of younger generations, suggest that memory can be rebuilt, even from fragments.

Legacy, in this story, is not grand or monumental—it is quiet, carved by hand, passed down in stories, and remembered in acts of service. The book argues that this, too, is a form of victory.