A Secular Age by Charles Taylor Summary, Analysis and Themes

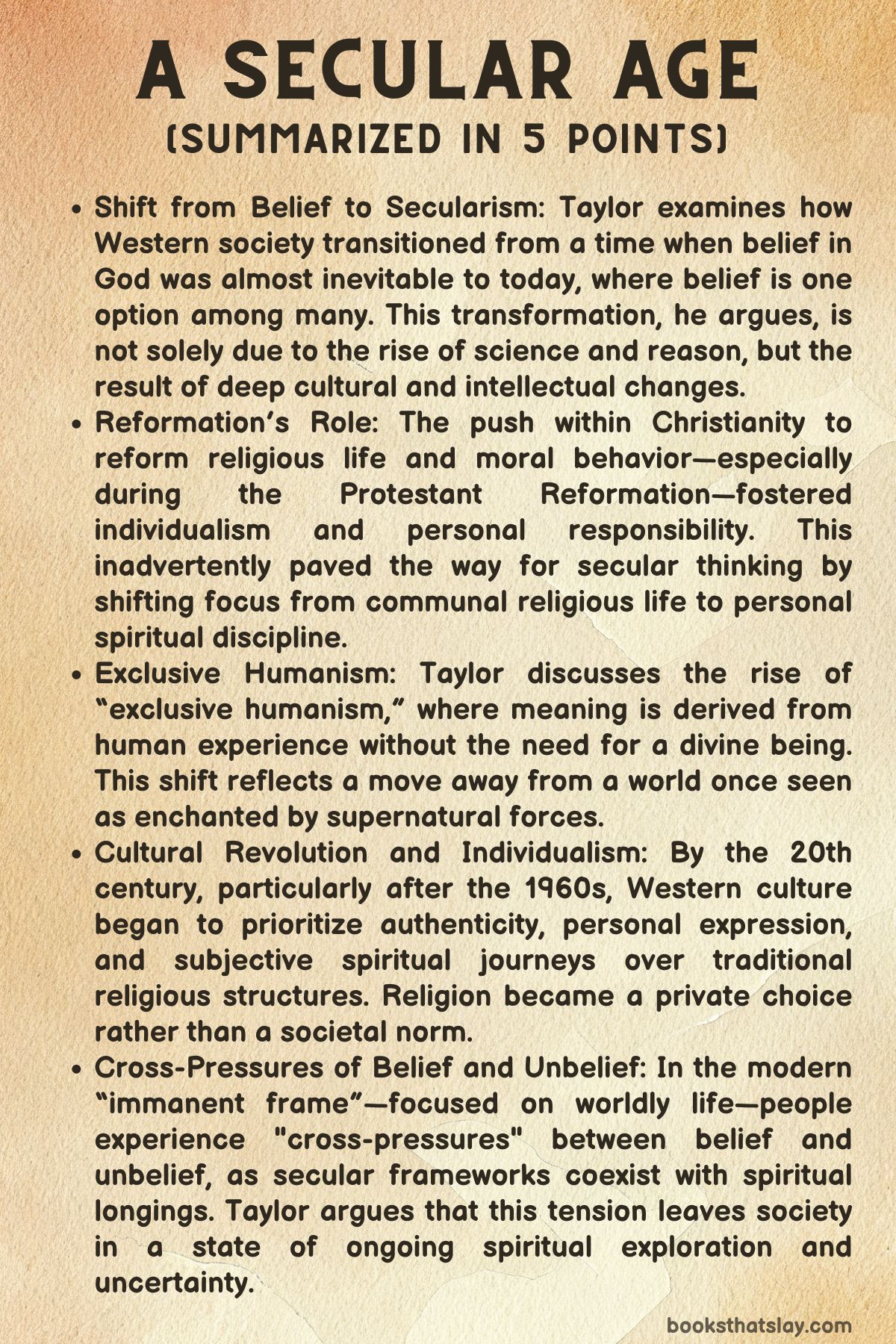

A Secular Age, written by philosopher Charles Taylor and published in 2007, examines how Western society transitioned from a time when belief in God was nearly unavoidable to a modern age where belief in God is just one of many possible perspectives.

Taylor challenges the simplistic notion that the rise of science and reason led to secularization, instead exploring complex historical, cultural, and intellectual shifts. His analysis delves into how modern identities, moral structures, and spiritual landscapes have evolved, providing a profound exploration of belief, doubt, and the social frameworks that shape contemporary secular life.

Summary

In A Secular Age, Charles Taylor explores the profound shift in Western culture from a time when belief in God was almost automatic to the present, where secularism and religious pluralism coexist.

This transformation isn’t simply the result of science and reason overtaking faith, but rather a complex reformation of how societies understand spirituality, human nature, and the universe.

Taylor traces this shift by examining how medieval life, once saturated with enchantment and divine mystery, gradually gave way to a more disenchanted, human-centered worldview, through the influence of changes within Christianity itself.

In the Middle Ages, society was steeped in religious belief. People perceived reality as deeply influenced by supernatural forces—be it God, angels, demons, or the sacraments of the Church.

However, the Reformation brought a drive toward heightened spiritual discipline, pushing everyone, not just the clergy, to aspire to a more intense religious life. This attempt to reform everyday spirituality inadvertently fostered a mindset where religious devotion became more individual and less communal.

Taylor argues that this disciplinary shift led to a more human-centered view of life, opening the door to modern secularism.

Taylor introduces the idea of “exclusive humanism,” a worldview where meaning and purpose are found within human experience alone, without recourse to the divine.

The Enlightenment, which emphasized reason and science, further accelerated this process, but Taylor contends that the roots of secularization lie deeper in Christian history.

By focusing on individual moral responsibility and the search for meaning in everyday life, reform movements within Christianity unintentionally laid the groundwork for a secular society where belief in God became optional.

Taylor then explores how these developments led to a modern culture that prizes authenticity and personal expression.

In the 20th century, especially after the 1960s, Western society began to value individual self-expression over conformity to traditional religious structures.

This shift marked the transition from an “age of mobilization,” where religious institutions played a central role in public life, to an “age of authenticity,” where personal spiritual journeys are privileged over institutionalized belief systems.

In this new cultural environment, religion becomes more of a personal choice, often detached from communal or national identities.

In the final sections, Taylor focuses on the “immanent frame,” a modern mindset that prioritizes worldly concerns over transcendent realities.

While many live comfortably in this secular space, it creates “cross pressures” between belief and unbelief, as people grapple with moral and existential questions in a world that no longer automatically assumes a divine order.

Taylor concludes by suggesting that we live in a time of uncertainty and spiritual searching, where both belief and unbelief face challenges from the deep human need for meaning, fullness, and connection to something beyond the self.

Analysis and Themes

The Construction of Secularization as a Historical Process

In A Secular Age, Charles Taylor presents secularization not as a simple absence of religion but as a complex historical construction. He rejects the reductionist theory that modernity emerged purely by subtracting religion from society and suggests that secularism is a product of broader intellectual, political, and social processes that unfolded over centuries.

Taylor emphasizes that secularization is not merely the decline of religious belief but involves a transformation of the social imaginary—a shared set of cultural norms, practices, and self-understandings. In the medieval world, belief in God was almost a given, embedded in the fabric of everyday life.

However, Taylor argues that the evolution of Deism, and later the rise of exclusive humanism, fundamentally redefined how individuals related to the divine. This shift moved from a God-centered to a human-centered worldview.

This transition is part of a larger, historically contingent narrative where secularism emerges not as the eradication of religion, but as a reorganization of spiritual life within new frameworks of human understanding.

The Role of Reform in Advancing Secularity and Exclusive Humanism

Taylor posits that the movement of Reform within Christianity—initially intended to elevate religious devotion and integrate all individuals into a higher spiritual realm—paradoxically catalyzed secularization. The Reformation sought to standardize piety and discipline within the community, moving away from a society that had accepted varying levels of spiritual engagement.

By imposing higher spiritual demands on the masses, this reformist zeal encouraged a more individualistic, human-centered approach to religious life. This ultimately led to the emergence of secular humanism.

Taylor introduces the concept of “exclusive humanism,” which marked a significant turning point in Western thought by relocating the sources of meaning and value from the transcendent to the human. This transition contributed to the rise of secular public spaces and a broader reorientation toward immanent rather than transcendent meanings.

The Cross-Pressures and Internal Tensions of the Modern Secular Age

Taylor’s exploration of modern secularism is framed by what he calls “cross-pressures”—the tensions between belief and unbelief, the sacred and the secular, that define contemporary Western society. Rather than experiencing secularization as a smooth progression toward unbelief, modern individuals navigate a “cross-pressured” reality where the pull of religious transcendence coexists with the disenchantment fostered by science, reason, and humanism.

This phenomenon creates a secular age that is deeply ambivalent. While the secular frame is characterized by the immanence of human life and material realities, individuals continue to encounter moments of existential unease.

Taylor’s idea of the “Nova effect” illustrates how the secular age generates a proliferation of spiritual and moral options, from religious belief to atheism, to various forms of spiritual but not religious practices. This explosion of possibilities does not eliminate religion but adds layers of complexity to the modern experience of faith and meaning.

The Evolution of the Moral and Epistemic Horizon in the Secular Age

Taylor traces the historical shifts in how Western societies have understood morality and knowledge, particularly through what he calls the Modern Moral Order. This new moral framework, emerging out of the Enlightenment, prioritizes individual rights, social justice, and the welfare of humanity over traditional religious moral systems.

Rooted in reason and disengaged from divine command, the Modern Moral Order operates within an epistemic framework that privileges empirical knowledge and rationality. Taylor suggests that this moral and epistemic horizon is both an achievement and a limitation of the secular age.

It allows for a universal ethic based on human dignity and equality but marginalizes the transcendent sources of moral inspiration that were central to religious life in pre-modern societies. In this sense, Taylor critiques the flattening of human experience that accompanies the dominance of reason and scientific knowledge.

The Immanent Frame and the Challenge of Transcendence in Secular Modernity

A central theme in A Secular Age is Taylor’s concept of the “immanent frame”—the intellectual and cultural framework within which modern individuals live. This frame focuses primarily on the material and immanent dimensions of existence while often marginalizing the transcendent.

Taylor argues that this immanent frame can either be open, allowing for the possibility of transcendence, or closed, where the material world is seen as the only reality. The immanent frame is not simply imposed by science or reason but is shaped by deeper cultural narratives and practices that position the secular as normative.

In such a frame, religious belief becomes a matter of personal choice rather than an unquestioned given, leading to what Taylor describes as a “fragilization” of faith. This creates an existential dilemma, where individuals may sense the inadequacy of a purely immanent worldview but struggle to articulate or engage with the transcendent.

The Expressive Turn and the Rise of Authenticity in Contemporary Secular Culture

The transition from the “Age of Mobilization” to the “Age of Authenticity” marks another crucial development in Taylor’s narrative of secularization. In the 1960s, Western society underwent a cultural revolution characterized by the rise of expressive individualism, where the pursuit of personal authenticity became a central moral value.

This shift has profound implications for religious and secular life alike. Individuals began to prioritize their personal experiences, emotions, and inner sense of truth over institutionalized forms of religion.

Taylor suggests that this turn toward authenticity eroded the authority of traditional religious institutions while simultaneously opening up new avenues for spiritual exploration. The modern pursuit of authenticity fosters a pluralistic landscape where individuals are free to craft their own moral and spiritual paths, drawing from a wide array of religious and secular sources.

However, this freedom is not without its challenges, as it can lead to fragmentation, isolation, and the loss of a shared sense of meaning and purpose.

The Ambiguities of Secular Morality and the Limits of Humanism

One of Taylor’s most compelling critiques in A Secular Age is his analysis of secular morality and its limitations. He argues that while secular humanism has succeeded in constructing an ethical system based on reason, empathy, and the pursuit of human flourishing, it often falls short in addressing the deeper human needs for meaning, transcendence, and moral wholeness.

Taylor acknowledges the achievements of secular moral frameworks, particularly in advancing human rights and social justice. However, he contends that they are often built on a “closed world structure,” which assumes that all moral and ethical considerations must remain within the immanent frame.

This, Taylor suggests, leads to a kind of moral flattening, where the deeper, more profound sources of moral inspiration—such as religious traditions that connect human life to a transcendent order—are marginalized or ignored. Taylor does not advocate for a return to pre-modern religious morality but calls for a more expansive understanding of the moral life.

The Post-Secular Horizon: Religious Renewal and Spiritual Pluralism in the Modern World

In the concluding sections of A Secular Age, Taylor explores the potential futures of religion and spirituality in a secular world. He suggests that we are entering a “post-secular” age, where the stark binaries between belief and unbelief, the sacred and the secular, are breaking down.

Taylor sees this as an era of religious searching, where individuals and communities are moving beyond traditional religious structures and experimenting with new forms of spiritual life. This post-secular horizon is characterized by a growing pluralism, where various religious, spiritual, and secular perspectives coexist and interact in complex ways.

Taylor argues that while traditional forms of organized religion may be in decline, the human aspiration toward transcendence and meaning persists. He points to phenomena such as the rise of Pentecostalism, the “spiritual but not religious” movement, and the revival of interest in mystical and contemplative practices as evidence of this ongoing search.

For Taylor, the future of religion in the secular age will be marked by a re-engagement with the transcendent. This re-engagement will not come through a return to old forms, but through a creative and pluralistic exploration of new spiritual possibilities.