Long Island Compromise Summary, Characters and Themes

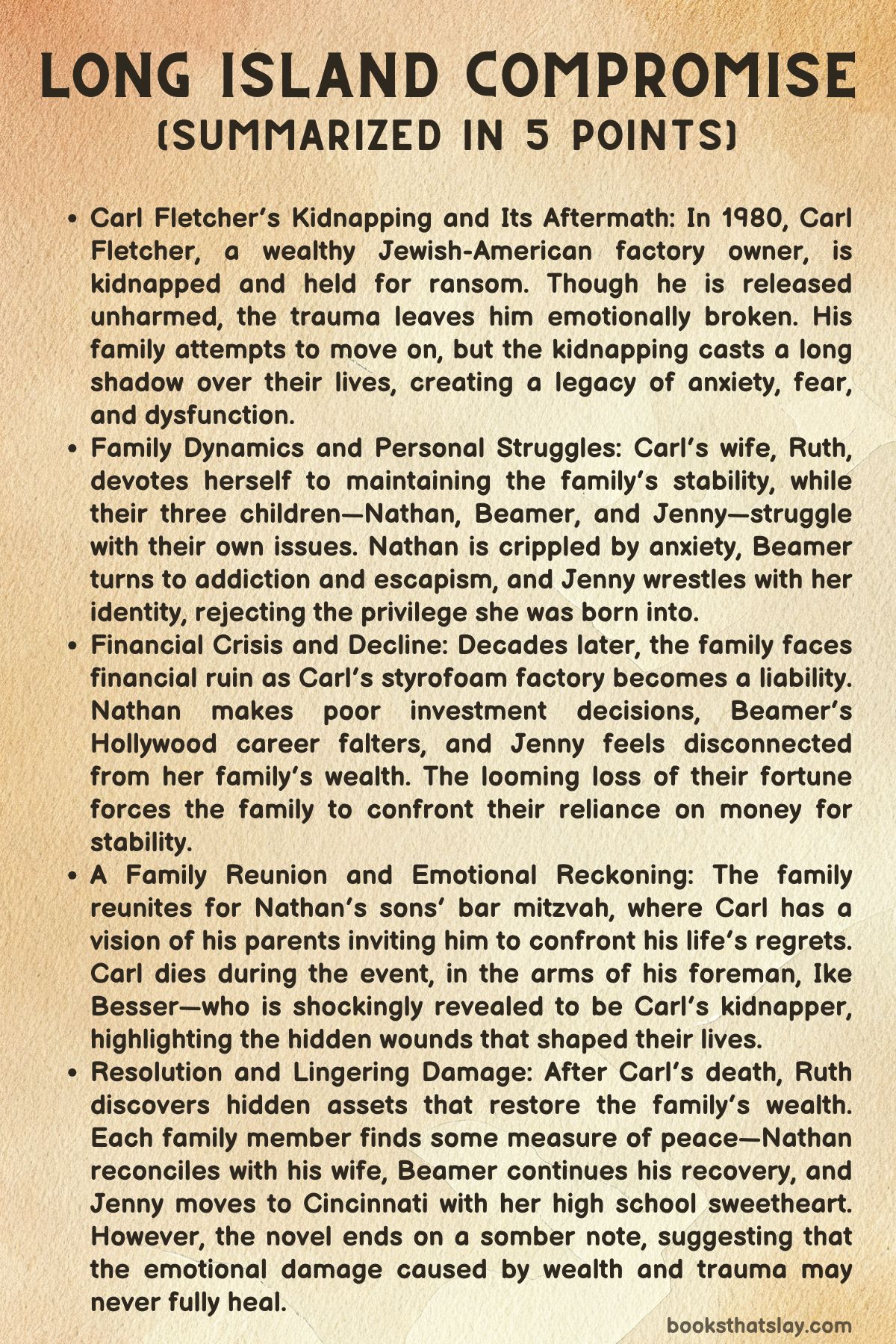

Long Island Compromise by Taffy Brodesser-Akner is a multigenerational family drama that explores how trauma, privilege, and inherited wealth shape the lives of a wealthy Jewish-American family on Long Island.

The novel revolves around Carl Fletcher’s kidnapping in 1980 and the ripple effects it causes over four decades. As the Fletcher family struggles with addiction, financial instability, and personal failures, they must confront the emotional damage caused by both their wealth and their unresolved past. The story tackles themes of legacy, survival, identity, and the complex ties that bind families through generations.

Summary

In 1980, Carl Fletcher, a wealthy Jewish-American owner of a styrofoam factory on Long Island, is kidnapped from his driveway. His wife, Ruth, receives a ransom demand of $500,000, which she delivers to secure Carl’s release.

Though Carl returns home after five days, he is deeply traumatized. Encouraged by his mother, Phyllis, to forget the incident, Carl attempts to move on, but his kidnapping leaves lasting emotional scars.

The family moves into a house on Phyllis’s estate, where Ruth gives birth to their daughter, Jenny, a few months later.

Decades pass, but the kidnapping continues to haunt the family. Carl struggles with unresolved PTSD, while Ruth devotes herself to protecting his emotional health. Their three children grow up affected by their family’s wealth and trauma in different ways.

Nathan, the eldest, is a lawyer who suffers from debilitating anxiety and fear of failure. Beamer, the second son, becomes a successful Hollywood screenwriter but falls into a destructive cycle of addiction to drugs, food, and sex.

Jenny, the youngest, spends her life rejecting her family’s wealth and striving to forge an independent identity.

The family’s fortunes begin to decline when Phyllis dies, and Carl’s styrofoam factory becomes a financial liability.

Nathan, already struggling with his personal finances, faces potential bankruptcy after sinking his savings into a fraudulent investment fund managed by his childhood bully, Mickey Mayer.

Meanwhile, Beamer’s Hollywood career is faltering. After a failed attempt to pitch a screenplay, he relapses into addiction. His friend Charlie challenges him to write something meaningful, but Beamer’s erratic behavior lands him in a rehabilitation facility after collapsing outside actor Mandy Patinkin’s house.

Jenny, who works for a graduate student union at Yale, finds herself caught between her bohemian values and her family’s legacy. She returns home for Phyllis’s funeral but struggles to reconcile her disdain for wealth with her longing for belonging. Ruth accuses Jenny of being detached from their family’s struggles.

Feeling lost, Jenny retreats to her family’s brownstone in Greenwich Village, where Ruth eventually finds her.

The family’s financial troubles worsen when Marjorie, Carl’s sister, under the influence of drugs, misinterprets Ruth’s instructions to sell the factory and instead burns it down.

Meanwhile, Nathan’s financial troubles come to light, and he confesses to his wife, Alyssa. Despite their financial uncertainty, the couple goes through with their sons’ bar mitzvah, where the entire family reunites.

At the bar mitzvah, Carl experiences a vision of his deceased mother and father, who invite him to confront his actions after the kidnapping.

He dies in the arms of Ike Besser, the factory foreman and, unbeknownst to everyone, Carl’s kidnapper. The revelation of Ike’s role underscores the unpredictability of life and the ways past traumas resurface.

In the aftermath, Ruth learns that Carl’s parents had hidden away a fortune in diamonds and Israel bonds.

This restores the family’s wealth, allowing Ruth to sell the Middle Rock estate and move to Greenwich Village. Nathan reconciles with his wife, Beamer continues his recovery, and Jenny finds peace by moving to Cincinnati with her high school sweetheart.

Yet the narrator—a collective voice representing the Middle Rock community—suggests that despite these changes, the Fletcher children remain emotionally damaged and unable to live independently of their family’s legacy.

Characters

Carl Fletcher

Carl Fletcher, the central figure in Long Island Compromise, is the patriarch of the Fletcher family, a wealthy Jewish-American businessman who owns a styrofoam factory. His life is permanently altered after his traumatic kidnapping in 1980.

The event leaves him psychologically scarred, unable to return to his normal life or manage the family business with the same vigor. Although Carl physically returns to his family, emotionally, he withdraws, unable to cope with the trauma he has experienced.

His withdrawal leads to a deep sense of alienation from his family, including his wife Ruth and their three children. As the years pass, Carl attempts to seek closure to his kidnapping, but the emotional damage is long-lasting.

His character embodies the complex relationship between wealth and trauma, where the comfort and safety provided by money are also the sources of the family’s dysfunction.

Ruth Fletcher

Ruth, Carl’s wife, is a central figure who carries much of the emotional burden of the family. She is deeply invested in protecting Carl’s mental health after the kidnapping, even at the expense of her own emotional well-being.

Ruth embodies the theme of survival; growing up without wealth, she is hyper-aware of the fragility of their status and does everything she can to protect the family’s fortune. Ruth is pragmatic, managing her children’s needs and tending to Carl’s psychological health, but her efforts are often in vain.

She has an especially strained relationship with Jenny, her only daughter, whose values and self-identity conflict with Ruth’s traditional views. Ruth’s sense of guilt about how wealth has affected her children’s ability to function in the world becomes a driving force in her decisions.

Her actions—such as pushing for the sale of the family estate and questioning whether she cursed herself by marrying Carl—reveal her deep internal conflict about the family’s material success and emotional stagnation.

Beamer

Beamer, the second son of Carl and Ruth, is a deeply troubled individual whose life is marked by addiction and emotional detachment. He lives in Los Angeles as a screenwriter, but his personal life is a mess, defined by substance abuse, toxic relationships, and a lack of direction.

Beamer’s emotional detachment can be traced back to the trauma of his father’s kidnapping. Though he was young at the time, the family’s inability to process the event or its emotional fallout deeply affected him.

His struggles with addiction and self-worth echo the family’s larger issues with wealth and legacy. Beamer’s character arc revolves around his attempts to reconcile with his past, though his journey is marked by constant relapse and self-doubt.

Despite his failed attempts to make something meaningful of his career, Beamer’s story highlights the effects of inherited trauma and privilege that plague the Fletcher family.

Nathan Fletcher

Nathan, the eldest son of Carl and Ruth, is characterized by his intense anxiety and fear of failure. His life is marked by an inability to fully engage with the world around him, both professionally and personally.

As a lawyer, Nathan avoids confrontational legal work and instead hides behind research, an indication of his desire to avoid risk and any potential emotional distress. His anxiety is compounded by the financial instability of the family business, which threatens the wealth he has always relied on.

Nathan’s relationship with his wife, Alyssa, is somewhat stable but strained due to his fear-driven decisions and his inability to confront their looming financial collapse. His emotional paralysis prevents him from being the father and husband he could be.

The bar mitzvah of his sons becomes a pivotal moment for him to confront his failures and fear. Nathan’s character represents the crippling effects of inherited anxiety and the burden of legacy, as he struggles to navigate life without taking risks.

Jenny Fletcher

Jenny, the only daughter of Carl and Ruth, is perhaps the most complex of the Fletcher children. She was born after the traumatic event of Carl’s kidnapping, and therefore did not experience the direct trauma, but she grew up in a family where the emotional scars of the event were deeply ingrained.

Jenny is highly intelligent, but she struggles to find her place in life. Her attempts to carve out a meaningful identity outside of her family’s wealth become a central theme of her narrative.

Jenny works at the graduate student union at Yale, and her desire for independence and purpose contrasts sharply with the wealth and privilege she was born into. However, her internal conflict is ever-present, as she is often torn between her bohemian aspirations and the life she feels nostalgic for when she returns home to Long Island.

Jenny’s character is also defined by her strained relationship with Ruth, who disapproves of Jenny’s rejection of their family’s wealth and the values that come with it. Ultimately, Jenny’s struggles with self-worth and identity highlight the theme of generational trauma and the challenge of escaping the shadow of inherited privilege.

Phyllis

Phyllis, Carl’s mother, plays a crucial but somewhat indirect role in the story. She represents the older generation’s mindset of denial and survival, urging Carl to “forget” the traumatic experience of his kidnapping.

Her influence is evident in the way the family handles Carl’s trauma, choosing to ignore it rather than confront it. Phyllis’s death marks a turning point for Ruth, who must face the family’s emotional and financial challenges without the support of her mother-in-law.

Phyllis’s role in the story underscores the generational differences in coping mechanisms and the tension between emotional repression and expression.

Marjorie

Marjorie, Carl’s sister, plays a smaller but significant role in the narrative. She becomes a catalyst for one of the novel’s more dramatic events, where, under the influence of drugs, she misinterprets Ruth’s instructions and inadvertently causes the destruction of the factory.

Marjorie’s character is defined by her confusion, disconnection from the family’s troubles, and emotional instability, which mirror the broader sense of dysfunction that defines the Fletcher family.

Mickey Mayer

Mickey Mayer, Nathan’s childhood friend and a key antagonist in the story, represents the darker side of the family’s wealth and business dealings. Mickey manages an investment fund that Nathan puts his savings into, only to learn that Mickey has misrepresented the fund’s success, leaving Nathan in a precarious financial position.

Mickey is a symbol of the greed, dishonesty, and manipulation that can accompany wealth, and his role in the novel serves as a reminder of the morally bankrupt elements that can emerge from privileged circles.

Alyssa

Alyssa, Nathan’s wife, serves as a foil to Nathan’s anxiety. While Nathan spirals into fear and financial ruin, Alyssa is committed to renovating their house and preparing for their sons’ bar mitzvah, representing a sense of optimism and control.

Despite her relatively stable outward appearance, Alyssa’s inability to understand Nathan’s emotional turmoil places strain on their marriage. Her willingness to push forward with her plans contrasts with Nathan’s paralysis.

Charlie Messinger

Charlie Messinger, Beamer’s best friend and a fellow screenwriter, represents an ideal of success and achievement that Beamer aspires to but cannot reach. Charlie’s challenge to Beamer to write something more personally meaningful than the Santiago films serves as a pivotal moment in Beamer’s journey.

Charlie’s role highlights the external pressure on Beamer to succeed and the inner conflict that prevents him from fully confronting his past and achieving emotional growth.

Ike Besser

Ike Besser, Carl’s loyal foreman, has a surprising and critical role in the plot’s conclusion. His secret identity as Carl’s kidnapper adds an unexpected twist to the narrative, revealing the blurred lines between loyalty and betrayal within the context of the family business.

Ike’s final act of holding Carl as he dies serves as a haunting conclusion to the story, emphasizing the long-lasting repercussions of trauma and the intricate dynamics of power, loyalty, and guilt.

Themes

The Paralyzing Legacy of Generational Trauma and Its Unrelenting Grip on Personal Identity

In Long Island Compromise, one of the most poignant and complicated themes is the enduring impact of generational trauma. The novel’s exploration of trauma begins with Carl Fletcher’s kidnapping, a harrowing event that he, his wife Ruth, and their children never truly recover from.

Carl’s PTSD becomes the unseen force that fractures the family, seeping into their lives and shaping their psychological and emotional trajectories. The impact of this singular traumatic event reverberates through the generations, distorting the children’s ability to form healthy relationships and function in the world.

Beamer, Nathan, and Jenny each embody the different ways trauma manifests in adulthood. Beamer’s addiction is a numbing response to his inability to confront his past, while Nathan’s crippling anxiety demonstrates a paralyzing fear of potential failure.

Jenny’s inner conflict centers on the unresolved tension between wanting independence and being tethered to the trauma of her family’s experiences. This generational cycle illustrates how trauma can shape and mold individuals in ways that are difficult to escape, even decades later.

The Illusion of Safety Provided by Wealth and the Crushing Burden It Imposes on Those Who Inherit It

Another critical theme in Long Island Compromise revolves around the paradox of wealth as both a protective shield and a suffocating burden.

Ruth’s anxiety about her children’s inability to survive without their inherited wealth highlights how financial stability, while offering a semblance of security, also robs individuals of the opportunity to learn resilience and self-sufficiency.

Ruth, raised without wealth, constantly wrestles with the fear that her children’s comfortable lives will leave them unprepared for real hardship. This theme is tied to the psychological damage caused by the kidnapping, where Carl’s wealth—which made him a target—also cushioned him and his family from the worst possible outcomes.

Yet, over time, the Fletchers’ fortune dwindles, and the façade of security begins to crack. The financial collapse forces Ruth and her children to confront their reliance on wealth, which they now realize is not the lasting solution to their personal and familial issues.

The story paints a vivid picture of how affluence, rather than providing freedom, often becomes a cage that limits personal growth and emotional survival.

The Hollow Pursuit of Success and the Paradox of Self-Fulfillment in a World Governed by Appearance

A theme that runs deeply through the characters’ experiences in Long Island Compromise is the hollow pursuit of success, particularly in the context of their wealth-driven and image-obsessed world.

The novel critiques not only the emptiness of pursuing professional or material success but also the absurd lengths the Fletchers go to in order to maintain their façade of having it all.

Beamer’s journey as a screenwriter in Hollywood epitomizes this paradox: despite achieving a degree of success with his Santiago Trilogy, he is ultimately dissatisfied and driven by an insatiable need for more—more money, more fame, more numbness.

His inability to grapple with his past and the failures in his personal life reflect the futility of achieving success when emotional stability and self-awareness are absent.

Similarly, Nathan’s career as a lawyer is stunted by his crippling anxiety, further illustrating how the desire for success can actually prevent people from living fully and meaningfully.

Jenny’s experience reflects another layer of this pursuit, as she spends years at Yale, caught between the quest for intellectual success and her desire to carve out an identity that is independent of her family’s legacy.

The theme reveals that, in their world, success is a mirage—something pursued and cherished, yet ultimately hollow and incapable of delivering the emotional and psychological fulfillment that the characters desperately crave.

The Subversive and Unspoken Power of Family Dynamics in Shaping Identity, Values, and Survival

The theme of family dynamics is intricately woven throughout the novel, as the Fletchers’ interactions with one another both constrain and define their individual identities.

Ruth’s marriage to Carl, which is rooted in both love and his wealth, becomes a source of tension as she grows increasingly resentful of how their children have been shaped by the very comforts that should have protected them.

Her need to maintain control over her family, often at the expense of their autonomy, is a manifestation of her own insecurities about their survival without the safety net of their inherited wealth. Similarly, Ruth’s complex relationship with Jenny, whom she views as having rejected the family’s values, is reflective of a larger generational divide—one where the younger generation struggles with the weight of expectations placed upon them by their parents.

The siblings’ relationships with one another also reflect the fragmentation within the family: Beamer’s detachment from his siblings is a result of his inability to engage with his trauma, while Nathan’s anxiety leads him to shut down emotionally, creating a chasm between him and the rest of the family.

Jenny’s strained connection to both her mother and her brothers speaks to the difficulty of forging personal identity when one is constantly trying to navigate the conflicting pressures of familial loyalty, personal independence, and inherited responsibility.

These complex and often dysfunctional dynamics underline the idea that family, for better or for worse, is a formative force that leaves a lasting imprint on each member’s sense of self and their ability to survive in the world.

The Futility of Escaping One’s Past and the Illusion of Free Will in the Face of Unresolved History

Long Island Compromise presents a stark meditation on the futility of escaping one’s past and the elusive nature of free will when one is perpetually haunted by unresolved history. Despite their attempts to carve out different lives and identities, Carl’s children find themselves trapped by the legacies of both their wealth and their trauma.

Beamer’s escape into Hollywood, Jenny’s return to academia, and Nathan’s repeated failures at securing financial stability all illustrate the inescapable pull of their past. The notion that the past defines them is further illustrated by Carl’s own inability to move forward after his kidnapping, as he becomes obsessed with seeking closure from an event that has already defined the trajectory of his life.

This theme ties into the idea that history is not just something that happens in the past but is an ongoing force that controls the present and future. The novel posits that, for the Fletcher family, their personal histories—shaped by trauma, wealth, and societal expectations—are insurmountable, and no matter how much they strive to distance themselves from these influences, they are ultimately fated to confront them.

This exploration of historical determinism highlights the limits of individual agency and the ways in which the past continues to shape one’s reality, no matter how much one may try to escape it.

The Illusory Nature of the American Dream and the Struggles of the Privileged Class in Reconciling Reality with Fantasy

At its core, Long Island Compromise offers a pointed critique of the American Dream, particularly the version of it that the Fletcher family believes they are entitled to. For the Fletchers, the dream is built on a foundation of inherited wealth, social status, and material success, all of which provide them with a sense of entitlement that blinds them to the deeper existential struggles they face.

Carl’s kidnapping, for example, disrupts this idealized version of their reality, exposing the vulnerabilities that money and privilege cannot protect them from. As the novel progresses, the family’s diminishing fortune forces them to confront the fact that the dream they’ve been living is an illusion—one that cannot save them from their personal demons or guarantee their emotional well-being.

The story thus critiques the notion of the American Dream as something that is ultimately unattainable or unsustainable for those who inherit it without having earned it through their own labor or resilience.

The Fletchers’ inability to adapt to a world that no longer affords them the same privileges they once took for granted underscores the inherent fragility of the American Dream and highlights the difficulties faced by the privileged class when the world they’ve known starts to crumble.