The Other Valley Summary, Characters and Themes

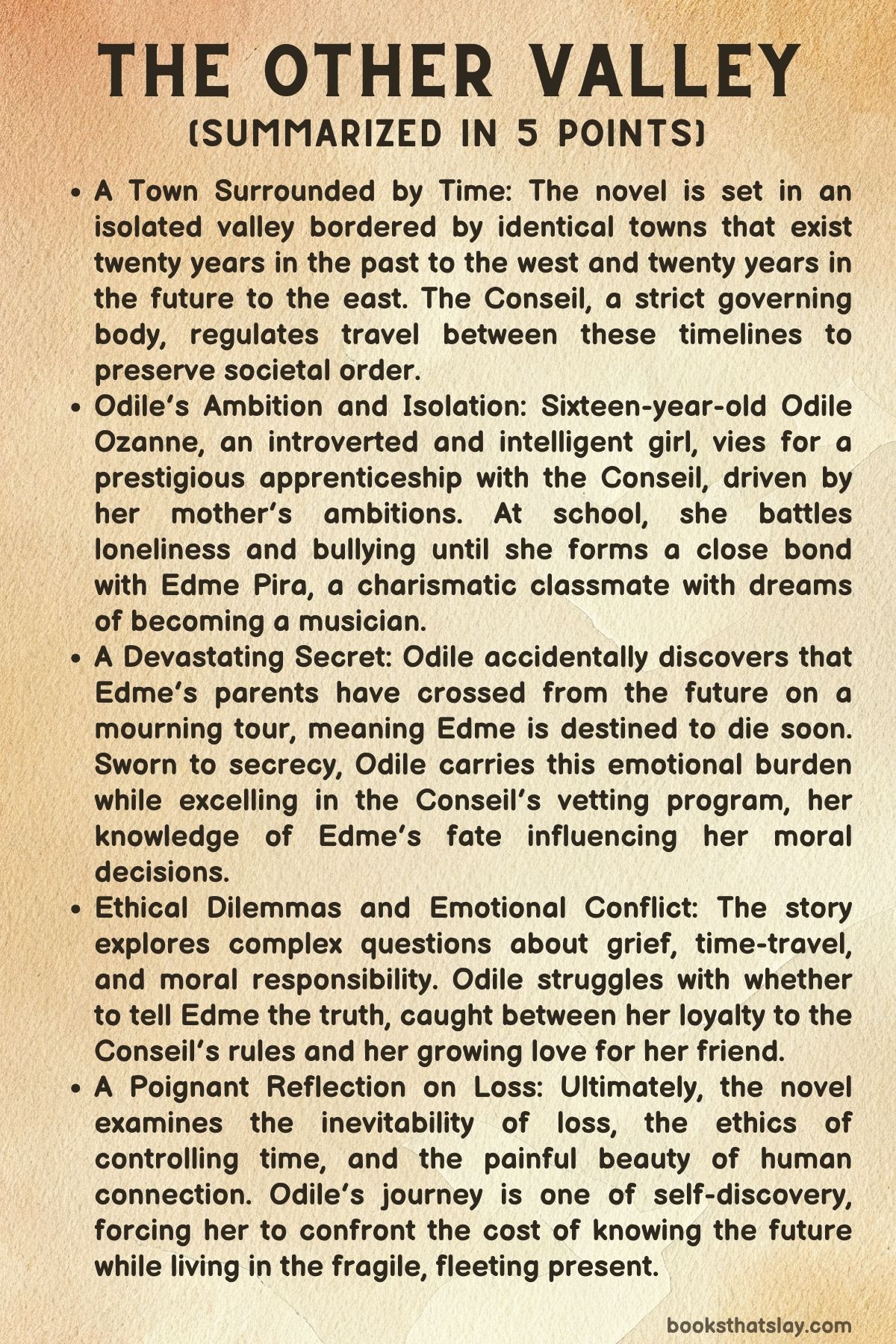

The Other Valley by Scott Alexander Howard is a hauntingly beautiful speculative novel set in an isolated town bordered by its own past and future. Here, time doesn’t flow linearly—it stretches across identical towns in opposite directions: to the west lies the past, and to the east, the future.

The story follows sixteen-year-old Odile Ozanne, an introverted, intelligent girl vying for a coveted seat on the Conseil, the governing body that controls the fragile balance between these timelines. But when Odile stumbles upon a devastating secret about her closest friend, she faces a moral dilemma that forces her to question not just the rules of her society, but the very nature of grief, love, and fate.

Summary

Odile Ozanne is a quiet, introspective sixteen-year-old living in a secluded valley unlike any other. Her town isn’t unique because of its landscape but because of what lies beyond its borders—identical versions of itself, stretched infinitely to the east and west.

The difference?

Time.

To the west, the valley exists twenty years in the past; to the east, it’s twenty years ahead. These borders are heavily guarded, and crossing them is strictly regulated by the Conseil, a powerful governing body tasked with preserving the integrity of the timeline.

Odile lives with her pragmatic, ambitious mother, who works in the Hôtel de Ville archives and is determined for Odile to secure a prestigious apprenticeship with the Conseil. Odile, however, is less certain. She’s shy, often bullied at school, and feels like an outsider after her childhood friend Clare moves away. Her days are marked by loneliness until she befriends Edme Pira and Alain Rosso—two boys who pull her into their lively, rebellious orbit.

Edme is everything Odile isn’t: charming, passionate, and musically gifted, dreaming of attending a conservatory against his parents’ more practical wishes. Their friendship slowly blossoms into something deeper, offering Odile both comfort and the painful awareness of how much she has to lose.

As part of the Conseil’s rigorous selection process, Odile must write an essay answering a deceptively simple question of crossing the border and choosing which direction to go.

While most candidates express a desire to visit either the past or future, Odile boldly claims she would choose to stay exactly where she is, believing that accepting loss is a necessary part of life.

This controversial stance catches the attention of her strict teacher, M. Pichegru, who—despite initial doubts—nominates her for the Conseil vetting program.

But Odile’s world shifts irreversibly when she accidentally witnesses a secret she was never meant to see. One day, near the border, she spots two masked visitors accompanied by a gendarme.

To her shock, she recognizes them as Edme’s parents. Their presence, shrouded in secrecy, can mean only one thing—they’ve traveled from the future on a mourning tour to see their son while he’s still alive. The realization hits Odile like a thunderclap: Edme is doomed to die in the near future.

This knowledge becomes both a burden and an unintended advantage. As she progresses through the Conseil’s vetting program, Odile excels, her sharp, detached reasoning standing out amid candidates who struggle with emotional biases. The program, overseen by the stern Mme Ivret, presents candidates with complex ethical dilemmas about time-travel petitions: Should someone be allowed to see a lost loved one if it risks societal stability?

Is preserving the timeline worth suppressing genuine human grief? Odile’s answers are chillingly precise, shaped by her secret—she knows firsthand the unbearable weight of forbidden knowledge.

Despite her growing success, Odile is haunted by Edme’s impending death. Their friendship deepens, and she grapples with an impossible choice: Should she tell him the truth, even if it violates the Conseil’s strict rules and endangers her future?

Or should she protect the timeline, suppressing her guilt and letting fate run its course?

The closer she grows to Edme, the more unbearable her silence becomes.

Odile’s moral crisis reaches a breaking point as she confronts not just the ethics of time-travel but the very essence of what it means to love and lose. The novel’s climax forces her to make a decision that will shape not only her future but also her understanding of grief, memory, and the fragile beauty of life’s impermanence.

In the end, The Other Valley isn’t just a story about time-travel; it’s a poignant exploration of human connection, the ethics of loss, and the bittersweet realization that even in a world where time loops endlessly, some things—like love and grief—are inescapably, achingly real.

Characters

Odile Ozanne

Odile Ozanne is the protagonist of The Other Valley, a sixteen-year-old girl who is intelligent, reserved, and introverted. She lives in a valley where time is controlled and separated into different regions, each representing a different temporal point: the past, the present, and the future.

Her quiet nature makes her socially isolated, and she struggles with loneliness, particularly after her childhood friend moves away. Throughout the novel, Odile’s internal conflict forms the backbone of the narrative.

She is initially pushed by her mother to apply for a position in the Conseil, the governing body that enforces time travel and cross-border restrictions. Although Odile shows little interest in the position, her mother’s expectations weigh heavily on her.

Odile is burdened by the discovery of Edme’s impending death, which makes her realize that knowing the future can create moral dilemmas. Her journey is not just about navigating the complexities of time travel but also understanding grief, friendship, and her own values.

As she excels in the Conseil vetting program, Odile grapples with the ethical implications of time travel and the consequences of her personal choices.

Edme Pira

Edme Pira is one of Odile’s closest friends and plays a pivotal role in her emotional growth. He is charming, passionate, and deeply talented in music, specifically as a violinist.

His warmth and carefree attitude stand in stark contrast to Odile’s quiet demeanor, and he becomes the person who truly understands her. Despite his outward confidence, Edme harbors his own inner struggles, particularly the pressure to follow a practical career path that conflicts with his dreams of becoming a musician.

Odile’s discovery of Edme’s tragic fate—his impending death—creates a significant emotional burden. Though Edme remains unaware of the exact circumstances surrounding his death, Odile’s knowledge of his future forces her to confront the ethical dilemma of whether to share the truth with him or protect him from this painful knowledge.

Edme represents the paradox of life’s impermanence—his brilliance and kindness are juxtaposed with the inevitability of his death, creating a complex layer of sadness and inevitability within the story.

Alain Rosso

Alain Rosso is Edme’s best friend and a key figure in Odile’s life. His personality provides a balance to the more serious and introspective nature of Odile.

Alain is loud, funny, and irreverent, bringing humor and lightheartedness to the otherwise somber tone of the story. He becomes one of Odile’s few true allies at school, offering support when she is bullied by her classmates.

His friendship with Odile grows over time, as he defends her from bullies and becomes a comforting presence in her life. Alain represents the theme of loyalty and the importance of genuine connections, especially in a world where emotional expression and connection can be stifled by societal rules and expectations.

While he is not privy to the heavy secret of Edme’s fate, Alain’s friendship and support are vital to Odile’s personal growth and emotional journey.

Jo Verdier

Jo Verdier is another candidate for the Conseil apprenticeship, an ambitious and confident boy who comes from a privileged background. His personality is marked by his strong sense of entitlement and a belief in his own importance.

Jo represents the societal expectations and pressures that Odile feels, particularly the pressure to succeed and conform to the roles defined by the Conseil. His character highlights the rigidity and elitism inherent in the society of the valley.

Jo’s relationship with Odile is more competitive than supportive, as they both vie for the same position within the Conseil. However, his ambition is tempered by his lack of emotional depth compared to the other characters.

Jo’s presence in the story serves to underscore the themes of societal control, ambition, and the ethical dilemmas of living in a society where rules and personal desires clash.

Henri Swain & Tom

Henri Swain and Tom are two bullies who torment Odile at school. They represent the cruelty and social hierarchies that prevail in Odile’s world.

Their behavior is a reflection of the rigid, exclusionary nature of society, where those who do not conform or fit into the expected mold are marginalized. Henri and Tom’s bullying exacerbates Odile’s sense of isolation and alienation, making her even more determined to avoid emotional entanglements.

Their antagonism serves as a sharp contrast to the genuine friendships Odile forms with Edme and Alain. Though they are minor characters in the broader narrative, Henri and Tom symbolize the toxic aspects of social structures that seek to diminish individual expression and vulnerability.

Mme Ivret

Mme Ivret is the stern and authoritarian conseillère overseeing the Conseil vetting program, where Odile and other candidates are tested to determine their suitability for a position within the Conseil. Mme Ivret embodies the rigidity and coldness of the system Odile is attempting to navigate.

Her approach to leadership is unemotional, focused solely on efficiency and adherence to the rules. She is a symbol of the controlling nature of the Conseil, which prioritizes order and stability over human connection and emotional authenticity.

Odile’s interactions with Mme Ivret force her to confront the limitations and potential dangers of a society governed by strict rules and the suppression of personal feelings. Mme Ivret’s character adds a layer of tension and moral complexity to Odile’s journey, as she questions whether the society’s emphasis on logic and control truly serves the well-being of its people.

M. Pichegru

M. Pichegru is Odile’s teacher, a man who is strict and emotionally distant. He plays a pivotal role in Odile’s nomination for the Conseil apprenticeship, despite her essay initially failing to impress him.

His decision to nominate Odile comes with an element of surprise and mystery, as it is unclear whether it is due to her potential or her accidental exposure to Edme’s fate. Pichegru’s role in the story is somewhat enigmatic, as he represents the authority of the educational system that pushes Odile toward the path of the Conseil.

He is a figure of detachment, emphasizing the importance of rationality and control, much like the Conseil itself. Through Pichegru, Odile confronts the concept of obedience to authority versus personal integrity, a theme that runs throughout the narrative.

Odile’s Mother

Odile’s mother is a pragmatic woman working in the Hôtel de Ville’s archives. She represents the societal pressure for Odile to succeed and conform to the expectations of the Conseil.

Her unfulfilled ambitions drive her to push Odile toward success, hoping that her daughter will follow a path that she herself could not. Though her love for Odile is evident, her vision for Odile’s future often feels more like an imposition than genuine support for Odile’s desires.

She embodies the generational pressures that influence Odile’s choices, creating a tension between Odile’s own wishes and her mother’s aspirations for her. This dynamic highlights the themes of family, expectation, and the cost of pursuing a path laid out by others.

Edme’s Parents (The Piras)

The Piras, Edme’s parents, are central to the emotional conflict of the story. Their masked visitation from the future reveals the tragic truth about Edme’s impending death.

As they cross the border to visit their son while he is still alive in Odile’s present, they unknowingly bring Odile closer to the heartbreaking secret of Edme’s fate. The Piras represent the difficult moral choices that come with time-travel: the desire to relive moments of loss and the ethical cost of doing so.

Their characters, though not as prominent as others, add depth to the novel’s exploration of grief and the human desire to change the inevitable. The Piras embody the emotional and moral challenges faced by those who interact with time-travel, raising questions about the consequences of altering the natural flow of life.

Themes

The Ethical Dilemmas of Time-Travel and Its Impact on Human Connection

One of the central themes in The Other Valley revolves around the ethical dilemmas posed by time-travel and its consequences on human relationships. The valley’s strict regulation of time-travel and visitation between different temporal zones suggests a society desperately trying to maintain emotional and societal balance.

This system, run by the Conseil, strives to prevent chaos caused by unregulated time-travel, but at what cost? Time-travel, in this world, isn’t just about revisiting the past or seeing the future; it is about manipulating grief and loss, offering a momentary chance to see a loved one again or revisit a key moment.

Yet, this practice raises a fundamental question: does it truly help people cope with grief, or does it merely delay the inevitable acceptance of loss? The dilemma that Odile faces—whether to follow the rules set by the Conseil or to act based on her personal conscience—captures this theme.

By allowing people to revisit their past or future selves, society risks robbing its citizens of genuine emotional growth, forcing them to repeatedly confront the same griefs without the chance to truly let go. The question of whether it is ethically right to sacrifice emotional health for the illusion of comfort is deeply explored through Odile’s internal struggles.

The Moral Costs of Conformity to a Rigid, Bureaucratic Authority

The Conseil, with its cold, bureaucratic authority, becomes a symbol of the tension between individual morality and societal control. At its core, the Conseil’s role is to enforce the idea that time should remain rigid and ordered, preventing people from stepping outside the constraints of the established rules.

It mirrors the ways in which societies often prioritize structure and control over the personal well-being of individuals. Odile’s own experiences within this system highlight the dangers of blind conformity.

The Conseil represents an institution that, despite its well-meaning purpose of preserving societal stability, suppresses individual freedoms and emotions. In Odile’s case, her success within the vetting program is tied not just to her logical reasoning, but to her unintentional knowledge of Edme’s tragic future, making her valuable to the Conseil’s control.

The emotional detachment demanded by the Conseil in its decision-making process highlights the disconnection between moral integrity and bureaucratic efficiency. This theme examines the moral costs of living in a society where rules are designed to prevent emotional chaos but, in doing so, stifle human connection and genuine moral decision-making.

The Clash Between Individual Grief and Societal Expectations: The Cost of Seeking Closure

A powerful theme in The Other Valley is the clash between individual grief and societal expectations. The society that Odile inhabits seems obsessed with providing people with an avenue to find closure for their emotional pain, particularly through the sanctioned use of time-travel.

However, the pursuit of this closure comes with profound emotional and societal consequences. The central idea is that the society’s need for closure—whether through revisiting the past or peeking into the future—conflicts with the personal process of grieving.

Odile, in her quiet contemplation, represents a counterpoint to this collective yearning for closure. She questions whether it is better to accept loss, without the artificial comfort provided by time-travel, or whether seeking those fleeting moments with the dead and the dying is worth the emotional turmoil it causes.

Her internal journey illustrates how the pressure to conform to societal norms around grief can prevent individuals from processing their emotions authentically. The pressure she faces to join the Conseil, an institution that regulates such practices, further underscores how societal expectations often force individuals into roles or decisions that align with collective ideals, even when they come at the cost of personal emotional health.

Navigating the Tension Between Self-Identity and External Expectations in the Shadow of Loss

Throughout the novel, Odile’s journey is one of self-discovery, marked by her struggle to define herself amidst the conflicting demands of society and her own feelings of isolation and loss. The overarching theme of self-identity emerges as Odile confronts not only the demands placed on her by others—particularly her mother’s ambitions for her to join the Conseil—but also the weight of personal grief, especially concerning Edme.

Her isolation at school and her distance from other people shape her identity as a quiet, introspective individual, but as her relationship with Edme deepens and she becomes more involved in the Conseil’s power structure, Odile finds herself forced to reconcile her sense of self with the roles society expects her to play.

The tension between these competing forces is especially pronounced when Odile uncovers the secret about Edme’s future death. The realization that she knows something crucial about his fate puts her in a position where she must decide between her personal connection to him and her obligation to the rules of the Conseil.

This theme delves into how grief, the weight of personal relationships, and external expectations can mold and reshape one’s identity, often in complex and painful ways.

The Intersection of Time, Memory, and the Inescapable Nature of Human Mortality

The concept of time in The Other Valley is not just a mechanical, linear progression but rather an emotional and psychological landscape that intertwines with the characters’ lives. Time-travel, in this world, functions as a way to escape or confront the inexorable reality of death and loss.

The recurring motif of the valley’s borders, separating the past, present, and future, serves as a metaphor for how people grapple with time and memory. Time itself, as controlled by the Conseil, is an attempt to impose order on what is inherently uncontrollable—the passage of life, the inevitability of death, and the persistence of memory.

Through Odile’s reflections and interactions, the narrative explores how time, particularly the experience of loss, is inextricably tied to memory. The practice of revisiting the past or peeking into the future raises profound questions about the role memory plays in shaping identity and how people might cling to memories in an attempt to escape the reality of mortality.

Odile’s internal struggle to understand the ethical implications of time-travel is a meditation on how people cope with time, and the deep emotional consequences that arise from trying to manipulate or alter the flow of their lives. Ultimately, the novel suggests that while time may be something to be controlled or escaped, it remains an inescapable truth that all individuals must face.