The Serviceberry Summary, Analysis and Themes

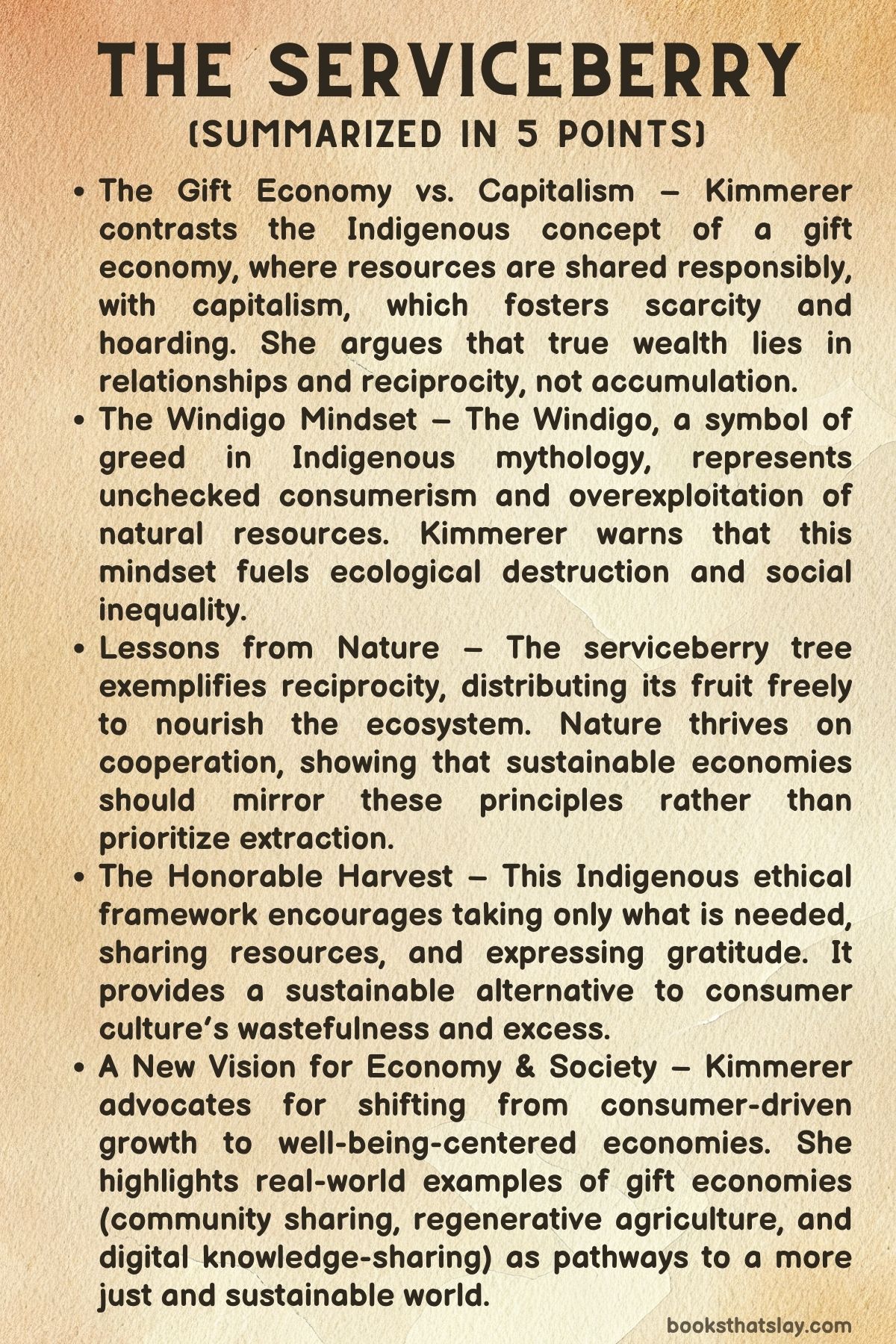

The Serviceberry: Abundance and Reciprocity in the Natural World by Robin Wall Kimmerer is a thought-provoking exploration of how we can rethink our relationship with nature, economy, and community through the lens of reciprocity.

Drawing from Indigenous wisdom, ecological science, and real-world examples, Kimmerer challenges the capitalist mindset of scarcity and hoarding. She offers an alternative—one rooted in generosity, mutual care, and sustainability. Using the serviceberry tree as a guiding metaphor, she illustrates how nature thrives on cooperation, not competition. The book invites readers to embrace a new model of abundance where giving, rather than accumulating, ensures collective well-being.

Summary

Robin Wall Kimmerer’s The Serviceberry: Abundance and Reciprocity in the Natural World is a powerful critique of modern economic systems and a call to embrace a more sustainable, community-oriented way of living.

Through Indigenous perspectives, ecological science, and personal storytelling, Kimmerer presents an alternative to capitalism—one based on the ethics of reciprocity. The serviceberry tree becomes a symbol of this alternative economy, demonstrating that nature flourishes through generosity rather than competition.

Kimmerer begins by contrasting capitalist economies with the Indigenous concept of a gift economy. In modern society, resources like food, water, and land are treated as commodities—bought, sold, and often hoarded. In contrast, Indigenous traditions see these resources as gifts that come with responsibilities.

She highlights how nature itself functions as a gift economy: trees offer fruit freely to animals, rivers provide water to the land, and ecosystems flourish through interdependence rather than ownership.

She introduces the Windigo mindset, a metaphor drawn from Indigenous mythology, symbolizing insatiable greed and consumption. Kimmerer argues that capitalism fosters this mindset, encouraging overexploitation of natural resources while prioritizing profit over sustainability.

The alternative, she suggests, is a culture of balance and responsibility—where taking from nature comes with the duty to give back.

Through the serviceberry tree, Kimmerer illustrates how nature distributes wealth. The tree produces an abundance of berries, which are freely shared with birds, animals, and humans.

In doing so, the tree ensures its own survival, as animals spread its seeds. This natural reciprocity, she argues, offers a blueprint for human economies—one that prioritizes mutual benefit rather than extraction.

She draws on the work of Elinor Ostrom, a Nobel Prize-winning economist, to challenge the mainstream economic belief that common resources are inevitably overused and depleted (a concept known as the Tragedy of the Commons).

Ostrom’s research proves that communities can sustainably manage shared resources through cooperation, aligning with Indigenous land stewardship practices that have existed for centuries.

Kimmerer also introduces the Honorable Harvest, an ethical framework for resource use.

This Indigenous principle emphasizes taking only what is needed, never wasting, and ensuring enough is left for others—including future generations. She contrasts this with modern consumer culture, where overconsumption and waste are the norm.

A major theme in these chapters is debunking the Tragedy of the Commons myth—the idea that shared resources will always be mismanaged unless privatized. Kimmerer counters this by showcasing Indigenous land management systems, which have successfully sustained natural resources for generations.

She argues that when people see land and resources as shared responsibilities rather than commodities, they are more likely to act as stewards rather than exploiters.

She then explores real-world examples of gift economies, from farmers giving away surplus produce to communities engaging in mutual aid. Digital platforms like Wikipedia also embody this principle, thriving on collective contribution rather than financial transactions.

These examples demonstrate that alternative economic models are not just theoretical—they already exist and can be expanded.

Kimmerer concludes with a call to action, urging a shift away from consumerism toward sustainability and reciprocity. She proposes rethinking economic indicators, moving beyond GDP growth to measure success through well-being, biodiversity, and social harmony.

Practical steps include supporting regenerative agriculture, reducing waste, and embracing community-based economies.

The final message is one of hope: reciprocity is not only possible but necessary for a sustainable future.

Kimmerer leaves readers with a crucial question—how will we respond to the Earth’s gifts?

Will we continue on a path of extraction and hoarding, or will we learn from nature and Indigenous wisdom to create a more just and abundant world?

In The Serviceberry, Kimmerer offers a compelling vision of an economy rooted in generosity, cooperation, and deep respect for the natural world—one that challenges readers to rethink what true wealth really means.

Analysis and Themes

Unlearning Scarcity and Embracing Abundance

Robin Wall Kimmerer’s exploration of the gift economy challenges the deeply ingrained capitalist mindset that equates value with scarcity. In the dominant economic system, worth is determined by limited supply—gold, diamonds, or land are valuable because they are finite and difficult to access.

This artificial scarcity leads to hoarding, privatization, and competition, reinforcing a worldview where survival depends on accumulation. Kimmerer dismantles this assumption by presenting an alternative model rooted in Indigenous knowledge, where abundance is not feared but embraced.

The serviceberry tree, by freely offering its fruit to birds, animals, and humans, demonstrates that wealth is not about individual possession but about the ability to nourish relationships. This notion unsettles the capitalist logic that sees sharing as weakness and instead reorients us toward an economy that prioritizes generosity over extraction.

By drawing from Indigenous traditions that recognize land and resources as communal gifts rather than commodities, Kimmerer forces readers to reconsider their participation in economic systems that exploit rather than sustain. The concept of a gift economy does not merely romanticize an alternative way of life but serves as a practical, functioning framework.

Communities that embrace reciprocity, whether through food-sharing initiatives or cooperative resource management, prove that sustainability is not a utopian dream but an active choice. Unlearning scarcity means rejecting the belief that survival necessitates relentless competition and instead acknowledging that a flourishing world is built on collective well-being rather than individual accumulation.

The Windigo Psyche i.e. The Insatiable Hunger That Devours the Earth

At the heart of Kimmerer’s critique of modern economic and environmental crises lies the figure of the Windigo—a creature from Anishinaabe mythology that embodies relentless greed, consuming endlessly but never feeling full. This metaphor extends far beyond folklore; it encapsulates the unchecked consumption driving environmental destruction, social inequality, and spiritual emptiness.

The Windigo psyche, according to Kimmerer, has been institutionalized within capitalist economies that valorize profit over sustainability and personal wealth over communal well-being. It is the force behind deforestation, industrial agriculture, and climate collapse—a mindset that sees the world as an endless storehouse of resources to be taken without consideration for consequences.

Unlike traditional cautionary tales in which monsters are external threats, Kimmerer warns that the Windigo resides within societal structures and, often, within ourselves. The desire for more—more land, more profit, more control—has become so normalized that it is mistaken for ambition rather than pathology.

However, Indigenous traditions offer an antidote to this mindset. An economy that recognizes the limits of the Earth’s generosity demands responsibility in exchange for sustenance.

The Honorable Harvest, a principle that guides ethical foraging and resource use, acts as a direct counterpoint to Windigo greed. It teaches restraint, gratitude, and reciprocity, emphasizing that taking without giving back is not just unsustainable but morally corrosive.

By acknowledging and confronting the Windigo within, societies can begin dismantling the systems that perpetuate its hunger. Instead, they can cultivate an ethic of sufficiency rather than excess.

Indigenous Stewardship as a Model for Collective Prosperity

One of the most persistent economic myths used to justify privatization is the so-called “Tragedy of the Commons.” This theory argues that shared resources will inevitably be depleted because individuals act selfishly, consuming as much as possible before others do.

This argument has been used to rationalize the enclosure of land, the commodification of water, and the destruction of communal ways of living. Kimmerer directly challenges this assumption by pointing to Indigenous land management practices that have long proven otherwise.

For centuries, Indigenous communities have successfully governed communal resources not through market-based control but through principles of respect, responsibility, and reciprocity. The land is not something to be owned but something to be cared for, ensuring its vitality for future generations.

Elinor Ostrom’s research, which Kimmerer references, provides empirical evidence that communal resource management does not inevitably lead to depletion. Instead, communities that operate with shared responsibility often sustain resources far better than privatized systems.

The serviceberry tree offers a natural illustration of this. Rather than hoarding its fruit for itself, it distributes its wealth in a way that ensures the entire ecosystem thrives.

Moving Beyond Monetary Metrics to Ecological and Social Flourishing

The modern world measures success through GDP, stock market growth, and financial accumulation. These metrics reinforce a vision of progress rooted in endless economic expansion.

However, Kimmerer questions whether this version of “growth” actually leads to well-being. GDP rises when forests are clear-cut, when oil is extracted, when consumer goods flood the market—but these activities devastate ecosystems, displace communities, and accelerate climate breakdown.

In this framework, destruction is mistaken for prosperity. Kimmerer argues that wealth must be redefined not in terms of monetary accumulation but through ecological health, community resilience, and the quality of relationships between people and the land.

Indigenous economic models measure abundance differently. A forest is not “valuable” because of the lumber it can provide but because of its capacity to sustain life.

A river is not an economic resource to be dammed and exploited but a living entity that nourishes all beings. Kimmerer’s call to rethink wealth challenges deeply entrenched notions of individual success.

Instead, she invites a broader vision—one where prosperity is measured not by stock prices but by biodiversity, social cohesion, and cultural vitality.

Resisting the Privatization of Information and the Commodification of Wisdom

Kimmerer’s discussion of the gift economy extends beyond material resources to the realm of knowledge. In a world where intellectual property is increasingly commodified, she makes a case for treating knowledge as a communal inheritance rather than a marketable product.

Indigenous wisdom has long been shared freely, passed down through generations not for individual gain but for collective survival. However, modern institutions have transformed knowledge into an economic asset, restricting access in ways that reinforce inequality and exclusion.

Platforms like Wikipedia, open-source software, and community learning initiatives offer alternative models that resist this trend. By making information freely available, these systems mirror the natural world’s abundance.

Just as ecosystems thrive through interdependence, human societies flourish when wisdom is treated as a gift meant to be exchanged, enriched, and passed on. Knowledge, like serviceberries, is meant to be shared rather than hoarded.

Reciprocity as the Only Path to Collective Survival

Kimmerer does not merely critique the existing economic order—she offers a radical reimagining of how humans can coexist with each other and the natural world.

The serviceberry tree is more than a plant; it is a living embodiment of an alternative way of being. It prioritizes giving over taking, balance over excess, and relationship over domination.

The gift economy she envisions is not an abstract ideal but a practical necessity. It challenges the foundations of capitalism and offers a path toward a future where all flourishing is mutual.

Through her blending of Indigenous wisdom and ecological science, she presents a vision of an economy where reciprocity, rather than profit, is the guiding principle.

If embraced, this vision could heal not just the Earth but our fractured human societies as well.