Heavenly Tyrant Summary, Characters and Themes

Heavenly Tyrant by Xiran Jay Zhao is a sweeping science-fantasy novel that continues the story of Wu Zetian, a fierce revolutionary determined to shatter divine tyranny and expose the lies that have upheld a centuries-long war. Set in a futuristic, war-torn Huaxia, this book explores the ethical cost of rebellion, the manipulation of truth, and the deep conflict between power and liberation.

After awakening a legendary war hero thought to be dead, Zetian must navigate brutal power plays, ideological warfare, and the crushing expectations placed on her as both a leader and a symbol. Through her volatile alliances and shifting strategies, she redefines what it means to rule—and to resist.

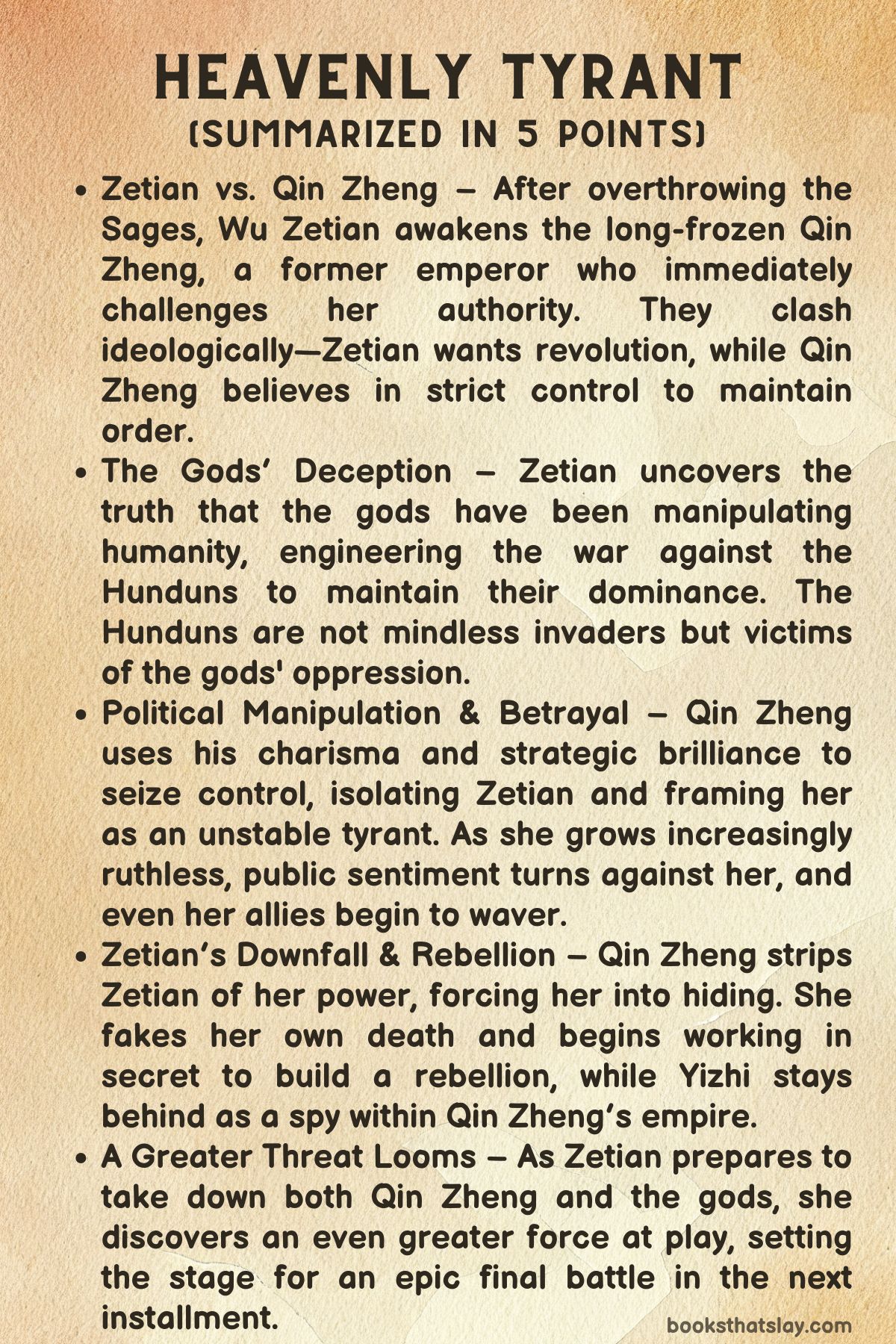

Summary

Heavenly Tyrant opens in a changed world. The once-immortal war hero Qin Zheng awakens from cryogenic suspension, expecting a society he once knew, only to find Huaxia reshaped by centuries of lies and bloodshed.

Wu Zetian, the teenage revolutionary who awakened him, co-pilots the Yellow Dragon—his old Chrysalis—and now leads an insurrection against the gods who, she discovers, never fought alien invaders, but rather perpetuated a false war for profit and control. Zetian believes the truth about the Hunduns—that they are sentient, misunderstood beings—must be revealed.

Qin Zheng, however, sees such truth as a destabilizing threat, arguing for the preservation of comforting illusions to maintain order. Their philosophical conflict sets the stage for a tense and unstable alliance.

Tension intensifies when Zetian, weakened in combat, is saved by Qin Zheng’s unexpected transformation of the Yellow Dragon into a humanoid subunit, defeating the threat with chilling precision. His calculated support leaves Zetian disturbed, especially when he admits he allowed her previous destructive actions as a test.

This catalyzes her psychological breakdown, manifesting in nightmarish visions and ultimately, imprisonment. She awakens stripped of her autonomy, in a lavish chamber, watched over by Qin Zheng—now styled “His Majesty.

” He has surgically altered her without consent and declared her Empress to preserve his rule. The move is political, not emotional, and it signals her symbolic role as a pawn within his regime.

While confined, Zetian becomes aware of how thoroughly Qin Zheng has reorganized power. Her co-pilot and former lover, Gao Yizhi, now serves as the Imperial Secretary, offering wealth and loyalty to secure status.

Struggling to reclaim her agency, Zetian undertakes a hunger strike and demands access to political tools and information. Qin Zheng resists, justifying his dominance as a form of protection.

Their relationship evolves into one of strained mutual recognition—he admires her strength but seeks to mold it to fit his system; she sees through his tactics yet cannot yet fully subvert them.

Through her servant Wan’er, who hides a radical lineage and intellect, Zetian gains insight into Huaxia’s oppressive structure, sparking a more calculated strategy. When Liu Che attacks her in a fit of rage, Qin Zheng intervenes publicly, naming her his future Empress.

Though it saves her, the move only underscores her powerlessness, her life a balancing act of symbolism and survival. Dressed in ceremonial armor, masked, and paraded as a loyal consort, Zetian resolves to endure and undermine from within.

As political unrest grows, a leak of a failed crowning ceremony spurs a crackdown. Qin Zheng imposes brutal punishments and mass surveillance, while Zetian proposes a staged pregnancy to reassure the public—an option she finds less horrifying than actual motherhood, which symbolizes the ultimate loss of control.

This ruse reveals lingering patriarchal attitudes, even among so-called revolutionaries like Sima Yi, who deride Zetian’s choices despite their strategic brilliance. Zetian’s past trauma and her deceased sister’s memory continue to shape her resistance, particularly against being reduced to a reproductive symbol.

Zetian’s shifting ideology comes into focus. Initially advocating for equality via conscription, she now questions whether true liberation must mimic male standards.

Nonetheless, she proceeds with training female pilots, whose enthusiastic admiration exposes the painful gulf between revolutionary rhetoric and reality. One pilot, Liang Yuhuan, proves herself extraordinarily gifted, hinting at the revolution’s potential but also at the dangerous stakes of war.

Seeking clarity, Zetian visits the converted apartment of her dead co-pilot Shimin. The place evokes intimate memories—both tender and traumatic—and draws her closer to Yizhi, despite emotional complications.

Her mental and spiritual training with Qin Zheng grows more intense, teetering between real and unreal. As she strengthens her control over elemental qì, she conspires in secret with Taiping to calculate an assault on the gods’ stronghold.

Their covert work, masked as romantic interaction, ensures secrecy. Wan’er, once jealous, is later brought into confidence, sharing a rare moment of affection with Taiping.

Zetian returns to the battlefield to confront a major disaster. A super-typhoon and a surprise Hundun attack breach the Great Wall due to compromised warning systems.

She fights alone until Liang Yuhuan arrives in a new Chrysalis, displaying astonishing combat ability. With their combined strength, they defend the breach, but the human cost is devastating.

Zetian discovers a child survivor in a ruined village, surrounded by corpses. The moment sears her conscience, showing the brutal cost of leadership and the fragility of ideological certainty.

The narrative builds to a climactic confrontation in the Heavenly Court, an enormous celestial pillar that functions as the gods’ center of power and as a hub for interstellar resource exploitation. Alongside Qin Zheng and Yizhi, Zetian learns the horrifying truth: Huaxia has been a planetary colony, exploited by Vivasi Minerals, a corporation orchestrating wars to mine spirit metal.

In a devastating encounter, she battles a twisted version of Shimin—now fused with metal and barely recognizable. She kills him in anguish, but hears his dying wish for restoration.

His spirit lingers, prompting her to retrieve remnants of their shared Chrysalis, the Vermilion Bird. A crash through the atmosphere fuses its fragments into a reborn vessel.

In their final gambit, the trio hijacks the Hive Queen, the largest enemy ship. Their guide, Helan, presents a political compromise: Huaxia will remain subservient under new terms.

But Zetian and Qin Zheng reject it. Together, they obliterate the Heavenly Court, symbolically and literally destroying the cosmic power that subjugated their world.

The victory is short-lived. Aware that Qin Zheng could easily replace divine rule with authoritarianism cloaked in revolution, Zetian stabs him through the heart to preserve the revolution’s spirit.

Though he survives through sheer force of will and mastery of spirit metal, she flees with Yizhi and Helan. They crash into the ocean and are saved by the reborn Vermilion Bird, which now contains a humanoid figure—Shimin, restored in some spiritual, metallic form.

In the epilogue, Qin Zheng clings to life in a mechanized state, obsessed with Zetian. He vows not to kill her but to reclaim her.

She, in turn, embraces the next phase of her mission—not just freedom from oppression, but the dismantling of systems that enabled it. Her revolution is far from over; it has merely evolved, shaped by love, loss, and hard-won clarity.

Characters

Wu Zetian

Wu Zetian stands as the heart of Heavenly Tyrant, a young woman transformed by trauma, war, and relentless determination. Initially introduced as a revolutionary who has torn down patriarchal structures and military lies, her journey is deeply personal and political.

Zetian grapples with power and agency from the moment she wakes imprisoned by Emperor Qin Zheng, facing a world where the revolution she started now spins out of her control. Her arc explores the erosion and reassembly of identity—stripped of her autonomy, technology, and public voice, she must navigate a dangerous chessboard where every move is both survival and subversion.

Zetian’s strength lies not only in her raw power or spiritual mastery, but in her refusal to be defined by the systems seeking to exploit her. Her evolution is shaped by betrayal and broken ideals, pushing her from fiery iconoclast to strategic stateswoman.

Even when cloaked in ceremony or chained in opulence, her mind sharpens, her convictions deepen, and her voice, though stifled, grows more precise. She refuses to be used as a symbol without substance, challenging not only those who oppose her, but those who claim to stand with her.

In love, grief, and revolution, Zetian wrestles with loss—of her lover Shimin, of ideological clarity, of innocence—but emerges as a leader forged in suffering and complexity, prepared to shatter cosmic systems if it means reclaiming freedom and redefining power on her own terms.

Qin Zheng

Qin Zheng, once the paragon of war and sacrifice, is resurrected not as a savior but as a tyrant cloaked in benevolent intent. Revered in ancient times for his revolutionary victories, he returns in Heavenly Tyrant as a master of manipulation, strategy, and survival.

His morality is forged in centuries-old pragmatism, his tactics honed by ruthless logic. While he claims to uphold order and resist divine oppression, Qin Zheng’s methods—coercion, surveillance, and psychological warfare—reveal a man deeply distrustful of human nature and incapable of relinquishing control.

He embodies a cold, paternalistic brand of governance, where autonomy is sacrificed for stability. His treatment of Zetian, from surgically altering her body without consent to imprisoning her under the guise of protection, shows his deeply ingrained belief that the ends justify the means.

And yet, his complexity cannot be ignored. He is not a mindless despot but a visionary burdened by his own trauma and clarity of vision.

His ideological conflict with Zetian is the narrative’s most potent tension: where she sees truth as liberating, he sees it as destabilizing; where she seeks liberation, he sees the necessity of order. Despite—or because of—his contradictions, Qin Zheng remains a haunting presence: both the architect of progress and its greatest obstacle, a man who yearns to build a new world yet cannot imagine doing so without binding it to his iron will.

Gao Yizhi

Gao Yizhi is the quiet, strategic counterpoint to the chaos of Heavenly Tyrant’s central duo. Initially Zetian’s co-pilot and romantic interest, Yizhi ascends through political maneuvering rather than brute force.

By offering his family estate to Qin Zheng and surrendering his wealth to the state, he secures a place within the imperial structure as Secretary—a role that grants him influence but demands compromise. His trajectory illustrates the theme of survival through adaptation; he avoids direct rebellion, instead embedding himself within the system.

Despite his proximity to power, Yizhi never relinquishes his loyalty to Zetian. Their emotional bond, intensified by shared grief over Shimin’s death and spiritual encounters with his memory, adds a tender undercurrent to the narrative.

Yet Yizhi’s choices raise questions about complicity and moral ambiguity. Is he preserving Zetian’s vision from within, or reshaping it for his own ends?

He is an enigma of affection, ambition, and restraint, navigating court politics with a diplomat’s calm even as war rages around him. His quiet intellect and loyalty make him invaluable, but his closeness to power also makes him a symbol of how revolutions bend under pressure, and how intimacy can be wielded as both shield and sword in the pursuit of change.

Wan’er

Wan’er emerges as one of Heavenly Tyrant’s most unexpected and quietly defiant figures. Originally introduced as a servant, her true depth unfolds through subtle rebellion and radical thought.

With a lineage rooted in resistance and a hidden education, Wan’er becomes an intellectual foil and emotional support for Zetian. Their early exchanges brim with subtext, where knowledge is passed not through declarations but through implication and shared glances.

Wan’er understands the cost of revolution on the individual level—the silenced, the unseen, the exploited—and helps Zetian bridge ideological shifts from militaristic feminism to a more nuanced liberation rooted in choice. Her relationship with Taiping further fleshes out her emotional world, revealing layers of jealousy, vulnerability, and eventual solidarity.

Wan’er’s radicalism isn’t loud or incendiary; it’s calculated, grounded in historical awareness, and imbued with quiet fire. As others rage or posture, Wan’er endures and educates, reminding Zetian—and the reader—that revolutions are not won only on the battlefield, but also in libraries, kitchens, and whispered alliances in the dark.

Taiping

Taiping, though initially a peripheral figure, grows into one of Heavenly Tyrant’s intellectual cornerstones. Disguised as a romantic partner to avoid divine scrutiny, Taiping’s true contributions lie in clandestine mathematical calculations and coded resistance.

Their work with Zetian to calculate the trajectory to the Heavenly Court becomes the cerebral parallel to the narrative’s emotional and physical battles. Taiping is a reminder that rebellion requires not just passion, but precision—that liberation must be engineered, not only felt.

Their relationship with Wan’er adds dimension to their otherwise mission-driven persona, offering a glimpse of tenderness and emotional intelligence beneath the analytical mind. Taiping’s presence underscores the theme of hidden brilliance, of how intellect can be weaponized against tyranny in the most unassuming packages.

They are not warriors, but they help aim the spear.

Liang Yuhuan

Liang Yuhuan symbolizes both hope and tragedy within Heavenly Tyrant’s revolutionary framework. A young girl inducted as one of the first female Chrysalis pilots, her role is emblematic of Zetian’s shifting ideology: once advocating forced equality through violence, Zetian now must reckon with the real cost of involving young girls in war.

Liang’s exceptional spiritual potential marks her as a prodigy, but her presence on the battlefield—especially during the breach at the Great Wall—forces Zetian to confront the weight of her choices. Liang is brave, competent, and earnest, but she is also a mirror to the empress’s youthful idealism and the brutality that follows its implementation.

She is both an achievement and a burden, a living reminder that revolution, no matter how righteous, extracts its price in blood and innocence.

Sima Yi

Sima Yi occupies the role of a traditionalist and skeptic, offering a counterpoint to Zetian’s and Qin Zheng’s visions. His disdain for Zetian’s symbolic pregnancy plan reveals the enduring patriarchal mindsets that persist even within revolutionary spaces.

He personifies the internal contradictions of rebellion—how old hierarchies can survive in new regimes, merely rebranded. Sima Yi does not wield enormous power in the narrative, but his presence reinforces the difficulty of ideological purging; progress is rarely pure, and even those claiming revolutionary intent may resist its most transformative tenets.

His voice adds realism to the political tableau—no regime, however radical, is immune to the ghosts of its past.

Helan

Helan is an alien guide with insider knowledge of the cosmic systems that oppress Huaxia, acting as a reluctant bridge between humanity and the intergalactic forces profiting from its subjugation. In Heavenly Tyrant, Helan provides crucial intel on Vivasi Minerals and the colonial structure of spirit metal extraction, but their usefulness is constantly mediated by ambivalence.

They are not fully aligned with Zetian’s goals, nor do they represent the enemy. Their function in the narrative is revelatory—exposing the scale of oppression beyond Huaxia—and their eventual role in the escape from the Heavenly Court positions them as a transitional character: one who enables but does not lead.

Helan’s presence underscores the moral complexity of decolonization: even those who offer liberation may benefit from systems of control.

Shimin

Though physically absent for much of Heavenly Tyrant, Shimin’s spiritual and emotional presence permeates the entire narrative. Once Zetian’s co-pilot and lover, he returns as a tragic symbol of what has been lost to war, experimentation, and the machinations of empire.

His transformation into a weaponized fusion of flesh and spirit metal serves as one of the novel’s most harrowing metaphors—a beloved body twisted by those in power into something monstrous. His final plea, “Make me whole,” captures the emotional thesis of the novel: that healing and revolution are intertwined, and that loss cannot always be reversed, only mourned.

Even in death, Shimin offers hope; the return of the Vermilion Bird, bearing a fragment of his spirit, suggests that love, memory, and identity can be reforged in fire and ruin. He is the soul behind the spectacle, the quiet center of Zetian’s storm.

Themes

Power and the Manipulation of Narrative

Throughout Heavenly Tyrant, power is shown not only as a tool of violence or conquest but as an apparatus deeply embedded in the control of stories, symbols, and historical truth. Qin Zheng’s initial decision to withhold the truth about the Hunduns and maintain the illusion of divine war underscores the importance of preserving a unifying myth, even if rooted in deception.

For him, mass belief is a fragile commodity that ensures cohesion, and destabilizing that with honesty would dismantle the social fabric. In contrast, Zetian believes that power must be reclaimed through truth, even if it risks destabilization.

Their conflicting philosophies illustrate how political legitimacy hinges on perception, not merely strength. When Zetian is imprisoned and presented as Empress for show while stripped of actual influence, it becomes clear that narratives are weaponized to control dissent and secure authority.

The evolution of Zetian from myth-breaker to participant in deception—like staging a pregnancy to appease the public—further complicates this theme, showing how even revolutionaries must sometimes manipulate the narrative to survive. The book ultimately argues that control over narrative is as potent as control over military or technological force, and that rewriting collective memory can be both revolutionary and oppressive depending on who wields that power.

Gender, Autonomy, and the Illusion of Liberation

Gendered control of the body and mind plays a persistent and harrowing role in Zetian’s arc. From the surgical reversal of her foot-binding without her consent to the pressure to bear children for the sake of state propaganda, her body becomes a battleground for patriarchal dominance.

Qin Zheng’s autocratic approach to “fixing” her body under the guise of health improvement mirrors institutional sexism that infantilizes and disempowers women under a paternalistic logic. Despite the revolutionary setting, women are still viewed as tools for political reproduction, and Zetian’s resistance to motherhood reflects a deeper fear of being reduced to a vessel.

Her earlier belief in forced conscription of women as a path to equality is later questioned, as she confronts the idea that true liberation must include choice, not merely access to violence. Liang Yuhuan’s induction as a pilot appears progressive but is shadowed by Zetian’s recognition that these girls are being led into war with little regard for their autonomy.

Even among revolutionaries, the systems that dictate female value remain deeply ingrained. This theme interrogates whether liberation that mimics patriarchal structures can ever be genuine, and whether survival under such regimes necessitates compromise or subversion.

The Fragility of Revolutionary Idealism

Zetian begins as a revolutionary icon, determined to dismantle gods and expose lies. However, over time, the contradictions and brutal costs of rebellion challenge her convictions.

The war economy, sustained on myths and human sacrifice, is not easily dismantled, and the systems replacing it often mirror the old in their reliance on surveillance, coercion, and manipulation. Her emotional collapse, catalyzed by guilt, betrayal, and exhaustion, is a reflection of the emotional toll idealism exacts when confronted with reality.

The revolution, once a source of clarity and purpose, becomes a site of moral ambiguity. She must constantly question whether her victories are worth their cost—especially when they involve sacrificing innocents, orchestrating public deceptions, or aligning with old enemies.

Even the presence of allies like Yizhi or Wan’er doesn’t fully restore her ideological certainty. Instead, her strategy evolves into something more calculated and less utopian, shaped by trauma and necessity.

By the novel’s end, the revolution is not a completed act but an evolving struggle marked by compromise, internal fractures, and a growing awareness that tearing down old structures does not automatically create justice.

Love, Loss, and the Persistence of Memory

Grief, emotional longing, and the struggle to preserve connection in the face of war shape Zetian’s internal world as much as political pressures do. Her memories of Shimin, especially when she visits his childhood home and battles his reanimated body, offer a poignant look into how love can endure even when its object is destroyed.

Shimin’s transformation into a mechanized monstrosity by Vivasi Minerals is not just tragic—it is emblematic of how even love is subject to industrial violence and exploitation. Zetian’s decision to kill him, tempered by his lingering plea to be made whole, underscores the impossibility of reunion but also the desire to preserve something sacred from ruin.

His partial resurrection at the end, as a new Vermilion Bird with his voice and name, is both miraculous and unsettling. It speaks to how love persists not as a static memory but as a constantly evolving force that changes form.

Her bond with Yizhi grows in tandem with this grief, grounded more in mutual understanding than passion, while her moment of intimacy with Wan’er shows that affection can take many forms. Love in Heavenly Tyrant is never isolated from power or politics—it is shaped, scarred, and sometimes preserved through both.

Colonization and Systemic Exploitation

The ultimate revelation—that Huaxia’s wars were orchestrated by Vivasi Minerals for the extraction of spirit metal—reframes the entire narrative through a colonial lens. The war with the Hunduns, the divine mandates, and the deification of rulers are not simply cultural or religious traditions—they are mechanisms for systemic resource extraction and population control.

The Heavenly Court, a celestial institution presented as divine, is unmasked as a colonial bureaucracy enforcing exploitation under the guise of cosmic order. This theme explodes the foundational myths of the society and reveals how deeply exploitation is embedded in institutions that claim benevolence.

It is not merely a critique of historical colonialism, but a warning about the ways corporate interests can masquerade as sacred duties. The destruction of the Heavenly Court is symbolic but incomplete—Qin Zheng’s survival suggests that new tyrants can rise even from righteous rebellion.

The machinery of exploitation does not end with a single victory. Zetian’s realization that revolution must extend beyond Huaxia to the very systems that manufactured their suffering transforms the scope of the narrative from national to interstellar.

This theme insists that colonization is not just an external imposition but a mindset and structure that must be dismantled at every level.