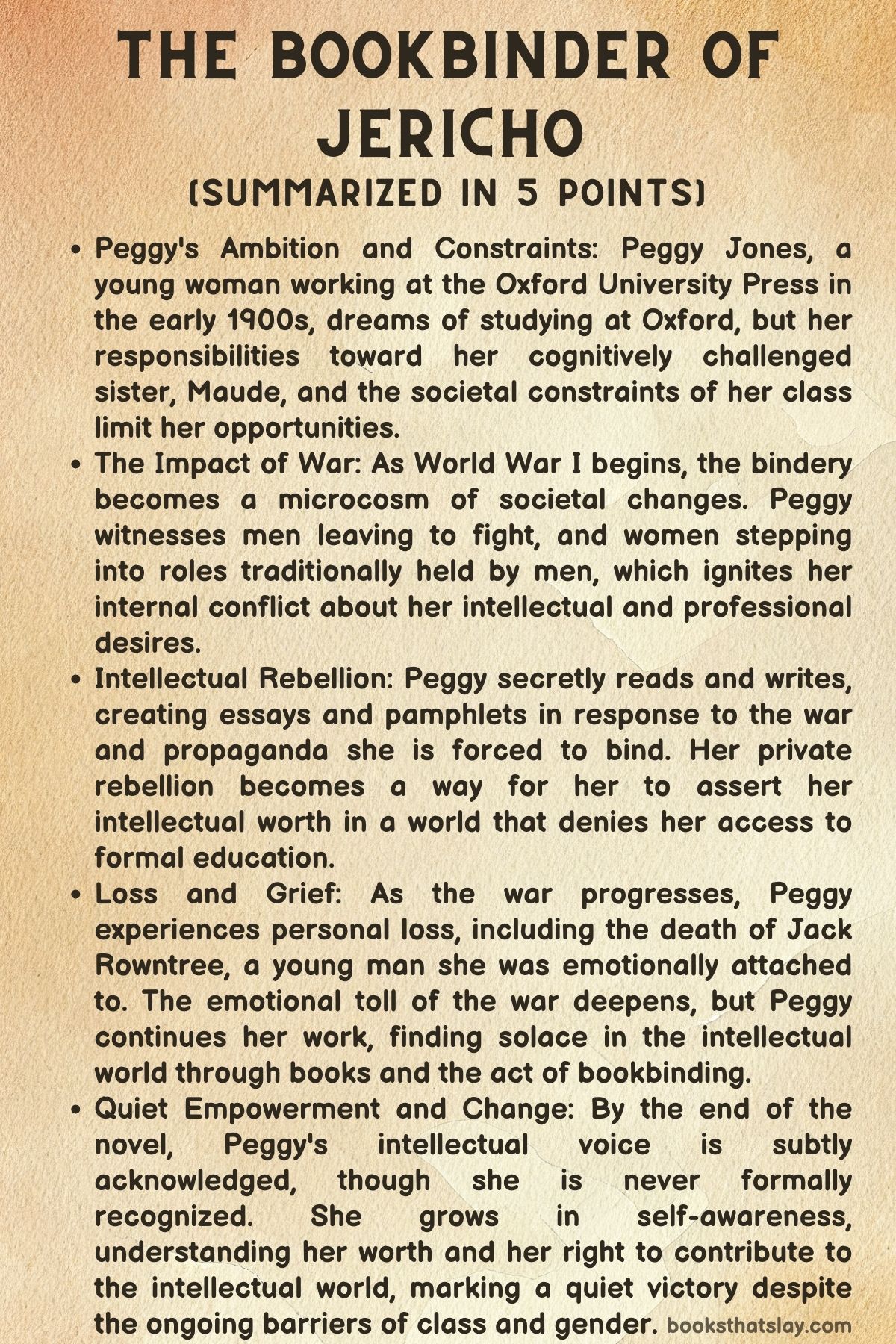

The Bookbinder of Jericho Summary, Characters and Themes

The Bookbinder of Jericho is a moving, quietly revolutionary novel by Pip Williams that follows the life of Peggy Jones, a working-class young woman in early 20th-century Oxford.

Employed at the Oxford University Press bindery, Peggy lives in a world of words she is allowed to touch but not to claim as her own. Against the backdrop of World War I, she wrestles with duty, grief, and a fierce hunger for knowledge. With deeply human characters and lyrical prose, the novel explores the tension between who writes history—and who binds it—shining a light on intellectual exclusion, sisterhood, and quiet resistance.

Summary

The Bookbinder of Jericho unfolds over five parts, each named after significant literary works, as we follow the intellectual and emotional journey of Peggy Jones, a bindery worker in Jericho, Oxford, during the years of World War I.

Peggy lives with her sister Maude, who has a developmental disability, and works at the Oxford University Press. She spends her days folding pages of classic texts, like Shakespeare and Homer, while yearning for the education just across the street at Oxford University—a world from which she is excluded by class, gender, and circumstance. Despite this, Peggy quietly rebels.

She reads the discarded pages meant only to be assembled, salvaging knowledge piece by piece, and begins to write her own reflections in secret.

Her love for Maude is unwavering, but their relationship also anchors Peggy in place. While she longs to rise—intellectually and socially—her caregiving responsibilities limit her choices. This duality between obligation and aspiration threads through the novel, creating a deeply human portrait of quiet sacrifice.

As the war intensifies, the bindery’s production shifts from classical literature to political pamphlets used for wartime propaganda. Peggy is unsettled by this transformation.

She begins questioning the truths and narratives she’s helping to publish. In response, she writes a series of anonymous pamphlets that challenge the jingoistic rhetoric of the Oxford establishment, reflecting on the humanity of the so-called enemy and the cost of glorifying sacrifice.

Her work circulates quietly, gaining attention and respect—though her authorship remains secret.

The story deepens emotionally and intellectually when Peggy is tasked with binding a book of German verse.

As she begins translating the poems with the help of dictionaries and friends, she finds herself drawn to their emotional resonance. In the face of rising anti-German sentiment, Peggy’s empathy and critical thinking lead her to interrogate the boundaries of nationalism.

Literature becomes her means of imagining a more complex and humane world.

The war’s personal toll escalates with the death of Jack Rowntree, a young compositor from the Press and Peggy’s friend—and perhaps more.

Jack had been one of the few people who saw Peggy and Maude fully. His loss is shattering, particularly for Maude, who struggles to process the grief. For Peggy, Jack’s death marks a turning point.

She realizes she must forge a path not in spite of the war and its grief, but because of it.

Peggy’s personal rebellion continues through her salvaging of broken books and assembling her own unofficial library—a metaphor for the fragmented knowledge and identities denied to women of her class.

Her bond with Mrs. Stoddard, a quiet mentor at the Press, offers support, while letters from Tilda, a family friend and former suffragette, introduce political complexity, revealing fractures within the feminist movement, especially regarding their wartime complicity.

In the final part of the novel, titled The Anatomy of Melancholy, Peggy confronts not only the aftermath of war but the deep psychological wounds it leaves behind. With Jack gone, Maude growing more independent, and the bindery evolving, Peggy stands on uncertain ground.

Yet she has gained something rare and powerful: a sense of her own worth. Her pamphlet is quietly acknowledged by someone in power, and though no doors to formal education swing open, her intellect and resilience are recognized.

The novel ends not with triumph, but transformation. Peggy doesn’t escape her world—but she reshapes it, book by book, idea by idea. She may not earn a place at Oxford, but she has built her own library of thought, her own odyssey of the mind.

Through grief, care, and resistance, The Bookbinder of Jericho becomes a testament to the stories that go unrecorded, and the voices that bind them together anyway.

Characters

Peggy Jones

Peggy is the central character of the novel, a young woman working at the Oxford University Press bindery in Jericho, Oxford. Throughout the book, her growth and inner turmoil provide the emotional core.

She is intelligent and ambitious, with a deep love for literature. However, her dreams of studying at Oxford are hindered by her class status and her sense of responsibility towards her sister, Maude, who has cognitive challenges.

Peggy’s intellectual yearnings are a recurring theme, and her secret acts of rebellion, such as writing essays and salvaging discarded texts, represent her desire for recognition in a world that limits her due to her gender and social standing. Her journey is marked by quiet acts of defiance against societal norms, particularly in her attempts to assert intellectual space for herself.

The war intensifies her internal conflict, as she watches many men leave for battle, and her personal relationships, especially with Jack Rowntree, complicate her emotional landscape. Despite the societal barriers, Peggy’s resilience and growing self-recognition mark a subtle but significant victory by the novel’s end.

Maude Jones

Maude, Peggy’s sister, plays a crucial role in shaping Peggy’s decisions. Maude’s cognitive challenges make her reliant on Peggy, creating a deeply emotional bond between them.

Maude represents innocence and purity, offering a counterpoint to Peggy’s intellectual aspirations and complex emotions. Her childlike nature and the way she clings to routine offer Peggy a sense of purpose, but also create an emotional trap that Peggy struggles to escape.

As the war progresses and Maude becomes more emotionally unpredictable, the strain on their relationship grows. This highlights Peggy’s internal conflict between familial duty and personal ambition.

Maude’s character serves to underscore the sacrifices Peggy makes, and her unique talents, such as her ability to fold paper, become symbolic of the domestic, unnoticed labor women often perform.

Jack Rowntree

Jack is a compositor’s apprentice and Peggy’s neighbor, who provides a sense of warmth and connection amidst the wartime chaos. His return from training offers a brief respite for Maude, who clings to his memory, and for Peggy, who begins to feel a deep emotional attachment to him.

Jack’s role is essential in illustrating the human cost of war, as his eventual death becomes a pivotal moment in the novel. His absence marks a shift in Peggy’s emotional growth, pushing her further into the intellectual and emotional spaces she occupies in secret.

Jack’s death is not just a personal loss for Peggy but also a symbol of the broader, tragic effects of the war on the lives of ordinary people.

Mrs. Stoddard

Mrs. Stoddard, Peggy’s supervisor at the bindery, is a quiet yet consistent advocate for Peggy’s potential. She recognizes Peggy’s intelligence and subtly encourages her to push beyond the limitations society places on her.

Mrs. Stoddard’s support contrasts with the rigidity of Mrs. Hogg, another supervisor, who represents the more conservative and hierarchical structure of the workplace.

Mrs. Stoddard’s encouragement is significant because it provides Peggy with the emotional and intellectual validation she needs to continue her private acts of rebellion. She embodies the quiet allies that sometimes exist in environments that might otherwise stifle a woman’s growth.

Mrs. Hogg

Mrs. Hogg represents the institutionalized authority within the bindery, a stark contrast to Mrs. Stoddard’s supportive demeanor. She is stricter and more focused on maintaining order within the workplace.

Mrs. Hogg symbolizes the societal expectations and gender roles that women like Peggy are expected to conform to. Her interactions with Peggy serve as a reminder of the barriers in the world Peggy seeks to transcend.

Tilda

Tilda, a suffragette friend of Peggy’s late mother, becomes an important political and feminist influence on Peggy. Disillusioned by the suffragette movement’s endorsement of war, Tilda offers Peggy a perspective on the conflicts within the feminist movement and the war’s impact on women’s rights.

Tilda’s letters provide Peggy with a broader view of political engagement and activism, offering a critique of performative patriotism. Through Tilda, Peggy is introduced to the intellectual and political dilemmas that women face during wartime, especially those who are critical of the war but find themselves in conflict with the mainstream feminist agenda.

These characters, each deeply intertwined with Peggy’s personal journey, represent the various forces—social, familial, intellectual, and political—that shape her path toward self-discovery and quiet rebellion. Through their interactions, the novel explores themes of duty, intellectual growth, and the subtle acts of defiance that women must often resort to in a world that limits their access to power and recognition.

Themes

The Complex Interplay of Gender, Class, and Intellectual Agency in Times of War

In The Bookbinder of Jericho, one of the most profound themes is the tension between gender, class, and the intellectual agency of women in early 20th-century England. Throughout the novel, Peggy’s life is defined by her proximity to knowledge and intellectual spaces, yet her social standing and gender prevent her from fully accessing them.

The bindery, a place where she works, symbolizes both the production of knowledge and her exclusion from the intellectual world. This tension is particularly evident in Peggy’s secret acts of rebellion, such as salvaging discarded pamphlets and binding them herself, which serves as both a literal and symbolic act of reclaiming intellectual power.

Peggy’s desire to study at Oxford University is repeatedly thwarted not only by her class status but also by the systemic gender barriers that restrict women from gaining formal recognition in academia. Her intellectual potential is stifled by the roles women are expected to occupy during wartime, which emphasize their domestic and auxiliary contributions rather than their academic or intellectual value.

The theme of gendered intellectual limitation is further highlighted by the fact that despite Peggy’s intelligence, she can never truly enter the academic sphere—her contributions remain anonymous and unofficial. This reinforces the idea that women’s intellectual voices, especially those from lower social classes, are marginalized.

The Metaphor of War and Its Intellectual Repercussions

The theme of war’s impact on intellectual and emotional lives emerges powerfully throughout the novel, especially through the experiences of Peggy as she navigates the complexities of her feelings about the war. As she binds pamphlets of wartime propaganda, the books she handles symbolize the ideological narratives that justify war, often dehumanizing the enemy and glorifying sacrifice.

However, Peggy’s growing discomfort with the war’s rhetoric leads her to engage in private acts of intellectual rebellion—through her secret writings and translations of German poetry, Peggy explores the shared humanity of both sides in the war. This theme deepens as the war becomes not just a political and physical conflict but an intellectual and moral one as well.

By translating German verse, Peggy confronts the division between her personal admiration for the beauty of the enemy’s culture and the public discourse that portrays them as wholly other and dehumanized. The war’s ideological impact on intellectual life is also explored through the manipulation of knowledge, where propaganda becomes the means by which information is disseminated to maintain nationalistic sentiment.

Peggy’s response to this is intellectual resistance, a personal struggle that mirrors larger societal tensions between the truth and the lies perpetuated by wartime narratives. Her acts of salvaging discarded materials and crafting her own critique serve as forms of quiet defiance in a world where knowledge is manipulated for political purposes.

Intellectual Reclamation and the Journey of Self-Recognition

Another important theme in the novel is intellectual reclamation, which intersects with Peggy’s journey toward self-recognition and empowerment. Throughout the book, Peggy repeatedly takes discarded materials—books, pamphlets, and poems—and binds them, creating her own intellectual library.

This act of “binding” becomes a metaphor for Peggy’s broader efforts to reclaim her voice and her place in the intellectual world, even as societal structures deny her these opportunities. This theme is particularly potent when Peggy anonymously submits a pamphlet critiquing the wartime propaganda produced by Oxford University Press.

In doing so, she takes an intellectual risk, asserting her voice in a space that would not accept her formally. The pamphlet, despite being written under a veil of anonymity, becomes a subtle victory for Peggy—a recognition of her intellectual capacity, even though it remains unacknowledged by the formal structures of academia.

Through these acts of intellectual reclamation, Peggy’s journey becomes one of self-empowerment, where she gradually comes to recognize her own worth and intellectual agency, even if society refuses to grant her the same recognition. This theme of intellectual liberation is closely tied to the broader feminist struggles of the time, with Peggy’s actions symbolizing a quiet rebellion against the norms that sought to suppress women’s intellectual and personal autonomy.

The Emotional and Existential Toll of War on Women’s Lives

The emotional and existential toll of war, particularly as experienced by women, emerges as a central theme in the final section of the novel. With Jack’s death and the mounting losses in Peggy’s community, the novel poignantly addresses the ways in which war’s impact extends beyond the battlefield.

For Peggy, the loss of Jack symbolizes not only the personal cost of war but also the existential weariness it brings to those left behind. The title of the final section, The Anatomy of Melancholy, underscores the emotional landscape of the novel, where grief, disillusionment, and the weight of lost potential pervade the characters’ lives.

Peggy’s ongoing emotional and intellectual struggles reflect a broader existential crisis—how does one find meaning in a world that is marked by sacrifice and loss? For women like Peggy, whose roles have been largely defined by care and domesticity, the war complicates their sense of self-worth and purpose.

Even as Peggy continues her intellectual work, it becomes clear that her personal rebellion is also an attempt to make sense of a world that has left her and others like her in emotional limbo. The theme of melancholy thus serves as a reflection of the emotional and psychological scars left by the war, particularly for women whose sacrifices are often overlooked or undervalued.

The Subversive Power of Quiet Acts of Rebellion

Finally, the novel explores the power of quiet, subversive acts of rebellion, which are central to Peggy’s growth and eventual self-recognition. Throughout the story, Peggy’s acts of defiance—whether through writing, translating, or salvaging books—serve as a form of resistance against the constraints placed upon her by society.

Unlike traditional forms of rebellion, Peggy’s actions are subtle and often go unnoticed, reflecting a different kind of power—one that does not seek immediate recognition but instead aims to carve out a space for intellectual and personal freedom. Her anonymous pamphlet, in particular, represents a radical form of self-expression, a small but significant act of intellectual defiance in a world that continually seeks to silence her voice.

The idea of quiet rebellion also resonates with the broader feminist movement of the time, which often faced institutional and societal resistance. Peggy’s journey suggests that true empowerment comes not from seeking external validation but from the internal recognition of one’s own worth, intellect, and right to exist as a full person, even in the face of systemic oppression.