Pathogenesis: A History of the World in Eight Plagues Summary and Analysis

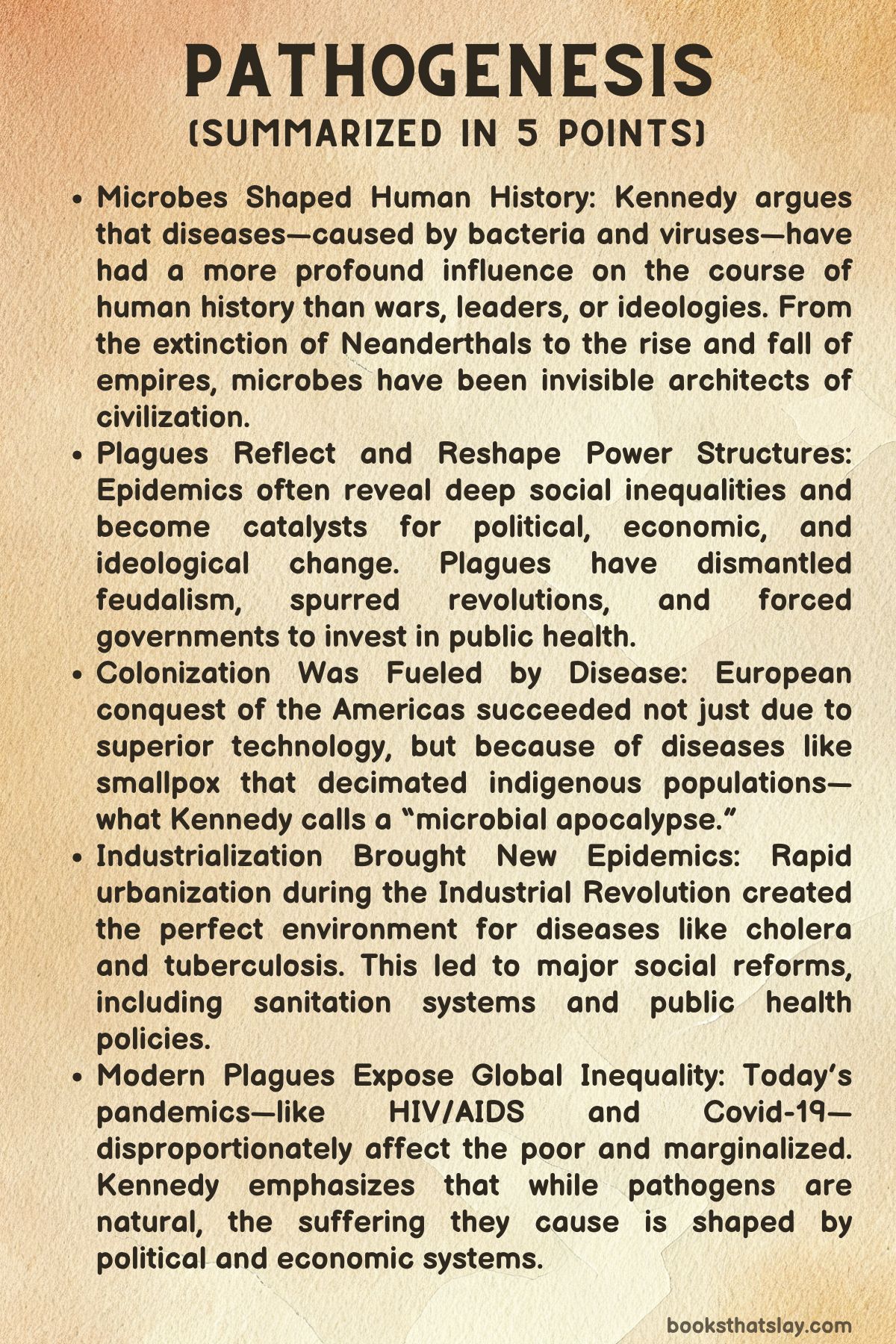

Pathogenesis by Jonathan Kennedy is a sweeping, provocative retelling of human history—not through battles, empires, or great men, but through the microbes that have shaped our destiny.

With wit, insight, and scientific rigor, Kennedy argues that bacteria and viruses have been more influential than any general or monarch in determining the course of civilizations. From the extinction of Neanderthals to the fall of Rome, from colonial conquest to modern inequality, plagues have rewritten the rules of survival and power. This isn’t just medical history—it’s a radical reframing of our past that challenges how we understand our species’ place in the world.

Summary

In the book, Kennedy offers a bold, microbial lens on the entirety of human history. He argues that plagues have not just accompanied major events but actively caused them—reshaping societies, rewriting empires, and redrawing the world map.

The book opens by grounding this microbial perspective in science and psychology. Drawing from Sigmund Freud’s concept of scientific “insults” to human ego, Kennedy presents pathogens as the ultimate de-centering force—unseen, untouchable, and yet profoundly influential. These microbes, he contends, are not just side characters in our story but co-authors of human civilization.

Chapter 1: Paleolithic Plagues

In the earliest era of human history, Kennedy explores a world shared by multiple human species—Neanderthals, Denisovans, and Homo sapiens. Rather than crediting Homo sapiens’ dominance to cognitive superiority alone, he proposes a striking theory: disease made the difference.

Through interbreeding, Homo sapiens transmitted pathogens to other hominins, who lacked resistance. However, they also acquired immunity-boosting genes—a dynamic Kennedy calls the “poison-antidote model.” In this way, early plagues acted as gatekeepers of survival, clearing the path for one species to dominate the Earth.

Chapter 2: Neolithic Plagues

With the advent of agriculture around 10,000 years ago, humanity’s relationship with microbes transformed. Settled life meant permanent dwellings, denser populations, and close proximity to domesticated animals—ideal conditions for zoonotic diseases. Diseases like smallpox and influenza began to flourish.

The first great epidemiological shift emerged: although life expectancy dropped due to disease, birth rates soared thanks to food surpluses, allowing populations to grow. Disease became a permanent feature of human life—not an anomaly but a consequence of our own social structures.

Chapter 3: Ancient Plagues

Turning to the great civilizations of antiquity—Egypt, Greece, Rome—Kennedy emphasizes how epidemics weren’t just disasters, but active agents of change. The Antonine Plague and Justinian Plague, for instance, devastated the Roman Empire, weakening its economy, military, and political unity.

Yet, plagues also enabled renewal: they disrupted established orders and opened space for new ideas, including the rise of Christianity. Microbes didn’t just bring death—they brought transformation.

Chapter 4: Medieval Plagues

The Black Death in the 14th century stands as the most famous pandemic in European history. It wiped out up to 60% of the population, collapsing feudal systems and reshaping economies. Labor shortages gave peasants new leverage, destabilizing aristocratic power.

Meanwhile, social reactions—scapegoating, mysticism, charity—revealed both the fear and the opportunity in plague-stricken societies. The plague shattered the medieval world and planted the seeds of modernity.

Chapter 5: Colonial Plagues

When Europeans arrived in the Americas, it wasn’t their weapons that conquered—it was their germs.

Smallpox, measles, and influenza obliterated indigenous populations, reducing resistance and enabling colonization. Kennedy frames this as a “microbial apocalypse,” where microbes—not explorers—were the most effective agents of empire.

This biological conquest also triggered global ecological transformations, including the Columbian Exchange of crops, animals, and diseases.

Chapter 6: Revolutionary Plagues

In the age of revolution, microbes once again shifted the tide. Yellow fever and malaria famously sabotaged Napoleon’s plans in the Americas, helping secure Haiti’s independence. Cholera outbreaks fueled public unrest in Europe, pushing governments toward sanitation reforms.

In this way, plagues didn’t just collapse regimes—they demanded ideological evolution, feeding the rise of liberalism, abolitionism, and public health policy.

Chapter 7: Industrial Plagues

Industrialization created cities teeming with disease. Cholera, typhoid, and tuberculosis thrived in overcrowded, unsanitary urban centers.

But this suffering sparked public health revolutions—sewers, water systems, and eventually socialized healthcare. Kennedy illustrates how these changes weren’t born of compassion alone but were political responses to the chaos disease brought.

Chapter 8: Plagues of Poverty

In our globalized world, plagues have become reflections of inequality. From HIV/AIDS to Covid-19, it’s the poor, the marginalized, and the Global South who bear the brunt. Kennedy critiques vaccine nationalism, underfunded healthcare, and systemic racism, arguing that the most dangerous pathogens today are rooted not just in biology—but in politics.

Ultimately, Pathogenesis is a profound reminder: to understand history, we must understand disease. And to survive the future, we must reckon with the structures that make some lives more vulnerable than others.

Themes

1. Microbes as Historical Agents

Rather than viewing plagues as background noise to human agency, Kennedy positions disease as a central driver of historical change. Pathogens:

- Wiped out rival human species (e.g. Neanderthals)

- Enabled European colonization through biological warfare (intentional or not)

- Shaped labor markets, revolutions, and public health infrastructure

This is a materialist approach to history, similar in style to Marxist historiography, but replacing class struggle with pathogen-host dynamics as the prime mover.

2. Epidemics and Inequality

Repeatedly, Kennedy shows how inequality creates vulnerability. From peasants in medieval Europe to enslaved Africans and modern marginalized communities, those with less power, worse housing, and poorer healthcare always suffer the most during epidemics.

He aligns with public health scholars who emphasize the social determinants of health, arguing that pandemics expose and deepen pre-existing injustices.

3. The Dual Role of Disease: Destruction and Innovation

Kennedy doesn’t only see plagues as destructive:

- They shatter stagnant systems, like feudalism after the Black Death.

- They prompt reform, like sanitation projects post-cholera.

- They catalyze new ideologies, like Christianity in the Roman Empire or revolutionary thought in the Enlightenment.

Plagues are thus presented as both harbingers of collapse and midwives of change.

4. A Non-Anthropocentric History

Inspired by thinkers like Freud and Darwin, Kennedy contributes to what he calls the “decentering of the human.” Just as Darwin removed us from the pinnacle of biology, Kennedy removes us from the center of history. His narrative is one of coevolution, not conquest alone.

Structural Analysis

Each chapter pairs a historical epoch with a type of plague, illustrating how microbes interacted with broader social developments:

| Chapter | Focus | Microbial Role |

| Paleolithic | Evolution & extinction of human species | Disease as a selective force |

| Neolithic | Rise of agriculture and settlement | New zoonoses from animals |

| Ancient | Collapse of empires | Mass epidemics destabilize institutions |

| Medieval | Black Death | Labor shifts, feudal breakdown |

| Colonial | European expansion | Pathogens as unintentional weapons |

| Revolutionary | 18th–19th century revolts | Diseases aiding uprisings |

| Industrial | Urbanization | Infrastructure reform from cholera, TB |

| Poverty | Modern inequality | Social injustice magnified by pandemics |

The book follows a chronological, yet thematic structure, making it accessible and interconnected.

Strengths of the Book

- Interdisciplinary integration: Kennedy blends genetics, epidemiology, anthropology, and history in a compelling way.

- Clear and engaging prose: Though the subject is scientific, the writing is highly readable.

- Moral urgency: The book ends with a plea for health equity, making it relevant post-COVID.

- Decolonial perspective: The colonial chapter especially avoids Eurocentric triumphalism, emphasizing how disease enabled conquest.

Critical Considerations

- Determinism risk: Some critics might argue that Kennedy leans too far into microbial determinism, downplaying human agency, culture, or economics in favor of germs.

- Overgeneralization: Broad global claims sometimes simplify complex historical events (e.g. attributing revolutions primarily to disease).

- Modern bias: The final chapter reads partly as a political manifesto (which may appeal or detract, depending on the reader’s perspective).

Comparative Works

This book sits well alongside:

- Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens – for its biological sweep of human history.

- William McNeill’s Plagues and Peoples – an earlier classic in the same genre.

- Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs, and Steel – for its focus on environmental determinism, though Kennedy is more focused on pathogens than geography.