Sisters of the Lost Nation Summary, Characters and Themes

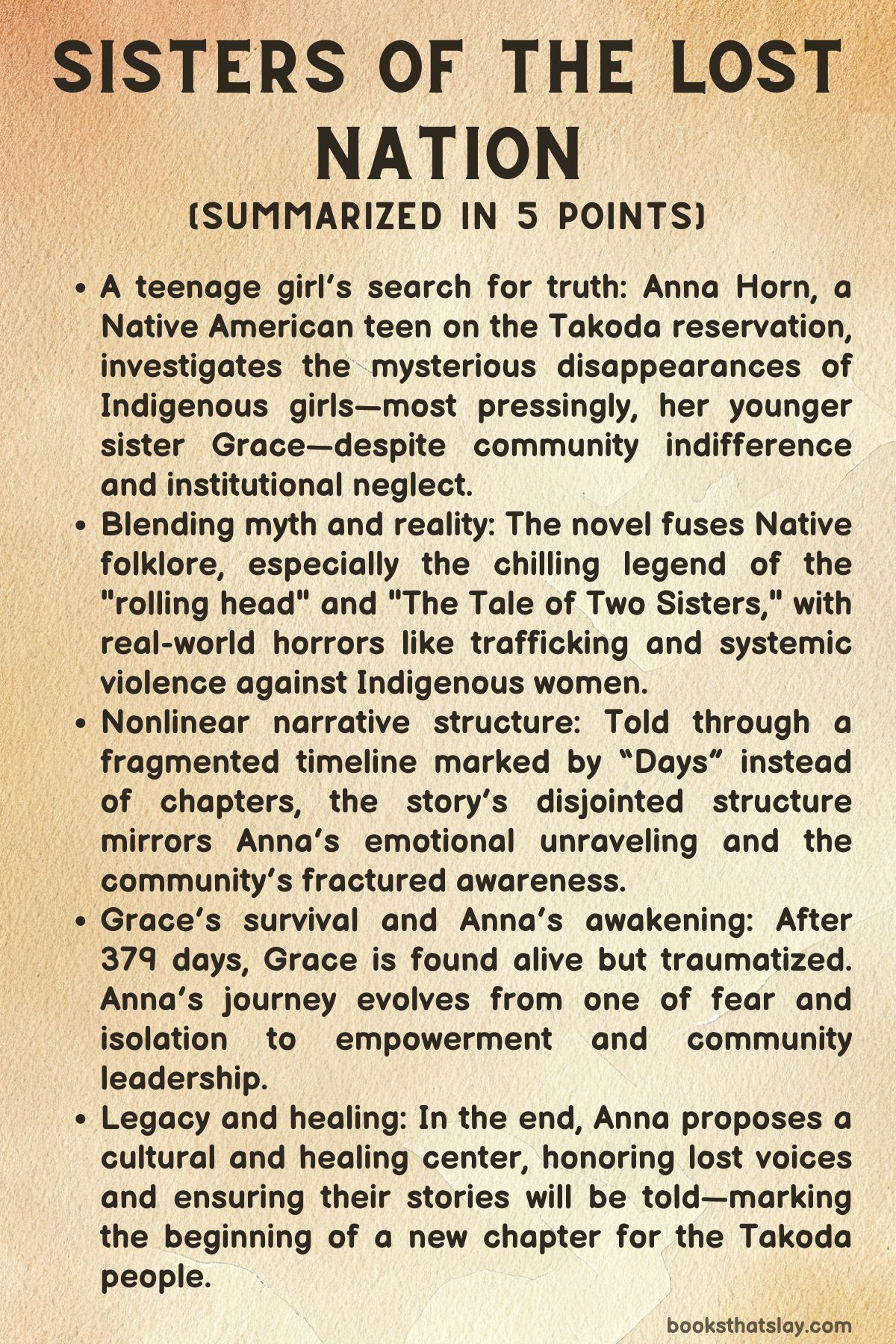

“Sisters of the Lost Nation” by Nick Medina is a haunting, emotionally charged novel that blends Indigenous folklore with modern-day horror to tell a story that is both culturally rich and socially urgent.

Set on the fictional Takoda reservation, the book follows Anna Horn, a determined Native American teenager, as she investigates a string of disappearances plaguing her community—girls vanishing without a trace, including her own sister. Structured around fragmented “Days” rather than traditional chapters, the novel weaves myth, trauma, and resilience into a powerful narrative about survival, identity, and the fight to reclaim lost voices in the face of generational silence and systemic neglect.

Summary

Sisters of the Lost Nation follows Anna Horn, a teenager living on the Takoda reservation, as she becomes entangled in a deeply personal and culturally significant mystery. Young Indigenous girls—including her own sister Grace—begin disappearing from their community, and while most look away or dismiss the events, Anna can’t.

What begins as concern quickly becomes obsession, as Anna struggles to connect the disturbing vanishing acts to the spiritual folklore she was raised on, particularly the legend of a rolling, disembodied head and a tale known as “The Story of Two Sisters.”

The story unfolds through a nonlinear structure, skipping between different days across two parts.

In Part I, we follow Anna’s growing awareness that something sinister is happening.

She works part-time at the tribal casino, a place that symbolizes both the economic survival and moral compromise of her people. There, she begins to sense something off—strangers lurking, girls being taken, and nobody seeming to care.

Grace, once a bright and lively spirit, becomes secretive and withdrawn. She begins disappearing for hours, skipping school, and acting like someone Anna no longer recognizes. As Anna investigates further, she uncovers signs of sex trafficking and possible connections between the missing girls and men at the casino.

At the same time, she is haunted—both metaphorically and literally—by visions of the rolling head from Takoda mythology, which seems to symbolize not just ancient curses but real-world cycles of violence against Indigenous women.

Throughout Part I, Anna’s attempts to sound the alarm are met with indifference. Her parents are overwhelmed, the tribal police are underfunded and under-resourced, and her classmates mock her. Even within her family, she’s treated like the troubled girl who sees ghosts.

This isolation only strengthens her resolve. Her connection to folklore deepens, and she starts believing that the stories from her ancestors might not be symbolic at all—they might be guiding her.

By Part II, Grace has vanished. Days pass. Weeks. Months. Anna channels her grief into relentless investigation. She begins to truly internalize the lessons from the legend of the two sisters.

In a key moment of symbolic power, Anna physically digs a hole in the earth—mirroring the tale—to “trap” the spiritual evil that she believes is claiming the women of her tribe.

Her symbolic act is followed by a miraculous development: Grace is found alive after 379 days in Cleveland, Ohio.

She has been exploited, discarded, but she survives. The family is reunited, but Grace’s scars—emotional and physical—are deep. Her recovery will be long, and the trauma never fully erased.

In the novel’s epilogue, set on Day 433, we find Anna changed. She’s no longer the teenager just trying to be heard. She has become a voice for others, a leader.

She proposes the creation of a Takoda Cultural, Educational, and Resource Center—an institution designed not only to preserve Indigenous traditions but to provide support and protection for future generations. The tribe agrees.

Anna’s transformation from a lonely girl haunted by myth to a community leader grounded in both tradition and action is the emotional core of the story. She learns that the old stories were never just bedtime tales; they were warnings, blueprints, and truths.

The novel closes on a quiet, powerful note. Anna walks the land, no longer searching, but building.

She writes the names of the missing, including Grace’s, almost. A plaque will one day carry those names. Until then, Anna will keep telling the stories, reminding her people—and the world—that every woman lost deserves to be found, remembered, and honored.

Characters

Anna Horn

Anna Horn is the protagonist of Sisters of the Lost Nation, whose journey is deeply rooted in both personal and cultural transformation. At the start of the novel, she is a typical teenager dealing with the challenges of school and family dynamics on the Takoda reservation.

However, as she becomes more involved in the mystery of the disappearing young women, including her own sister Grace, Anna evolves into a determined and resourceful investigator. She is skeptical at first about the supernatural stories passed down through her people, but as she unravels the horrors of human trafficking and violence, Anna learns to blend her cultural heritage with her personal strength.

By the end of the novel, she transcends her initial vulnerability and emerges as a symbol of resilience. Anna uses both traditional wisdom and modern grit to fight for justice and healing for her community.

Her character arc is a journey from disbelief and isolation to empowerment and leadership, culminating in her proposal for a cultural center aimed at preserving the history and aiding the recovery of those affected by the ongoing crisis of missing Indigenous women.

Grace Horn

Grace Horn, Anna’s younger sister, plays a pivotal role in the emotional and thematic development of the story. In Part I, she starts showing signs of distress, becoming increasingly distant and troubled, which foreshadows her eventual disappearance.

Grace is portrayed as a vulnerable yet deeply important character who embodies the trauma faced by Indigenous women, especially the ones who fall victim to violence or exploitation. Her abduction is a catalyst for Anna’s transformation and her deeper involvement in the struggle against systemic violence.

When Grace is found alive after being missing for 379 days, the scars she carries—both physical and emotional—serve as a harsh reminder of the brutality faced by many Native women. Despite the pain, Grace’s eventual return is a symbol of survival and resilience.

Her recovery is a long and painful process, but it becomes a key part of the story’s message about the necessity of cultural and community healing.

The Takoda Community

The Takoda community, though not a single character, is an essential part of the novel’s fabric. The reservation, rich in tradition but burdened by poverty and systemic neglect, plays a dual role: it is both a place of great beauty and cultural depth and a site of ongoing struggle against modern societal issues such as addiction, sex trafficking, and the invisibility of missing Native women.

The community’s response to the disappearance of young women is marked by apathy, with many residents and authorities either dismissing or downplaying the severity of the crisis. This institutional failure is evident in the lack of support from the tribal police and the wider legal system.

The community, as seen through the eyes of Anna, is at once a source of solace and pain, offering spiritual beliefs and folklore that shape her actions. However, it also harbors painful secrets that need to be confronted.

In Part II, the community begins to shift towards healing as Anna’s efforts to create a cultural and educational center gain support. This shift symbolizes the potential for growth and restoration.

The Rolling Head

The rolling head is a symbolic character rooted in the folklore of the Takoda people, representing both the ancient trauma and the spiritual forces at play in the novel. It first appears in Anna’s visions, initially thought to be a supernatural manifestation of the fear and violence surrounding the missing women.

Over time, it becomes a tangible symbol of the cycle of violence and loss that haunts the reservation. Anna’s engagement with the rolling head is both personal and spiritual.

The head is not merely a supernatural element; it becomes a metaphor for the real-world horrors inflicted upon her community. In Part II, when Anna confronts the rolling head in the context of her search for Grace, it signifies her struggle to break free from the cycle of violence.

Ultimately, this confrontation leads to her physical and spiritual encounter with the darkness that has haunted her people for generations. The rolling head thus represents the intersection of myth and reality, showing how deeply ingrained cultural stories can offer profound insights into modern-day struggles.

Themes

Cultural Reclamation and Resilience in the Face of Trauma

The novel Sisters of the Lost Nation delves deeply into the theme of cultural reclamation as a vital tool for survival and healing within Indigenous communities. Throughout the narrative, Anna’s journey is marked by a struggle to both reconnect with and preserve the cultural and spiritual legacies of her Takoda people, despite overwhelming odds.

As Anna uncovers the disturbing realities of missing Indigenous women and the neglect of systemic authorities, she finds solace and strength in her ancestral folklore. These stories, such as The Tale of Two Sisters, are not mere mythological relics but living, breathing elements that guide her through the darkness.

The traditional tales, initially viewed with skepticism, gradually shift from folklore to prophetic tools that offer wisdom and a path forward in times of crisis. The establishment of a Takoda Cultural, Educational, and Resource Center by Anna at the conclusion of Part II symbolizes a move from passive inheritance to active stewardship of cultural knowledge.

This initiative is a beacon of hope, aiming to protect future generations from the cyclical violence faced by Indigenous women, while honoring the historical and ongoing struggles of the community.

The Interplay Between Supernatural Beliefs and Modern Realities of Violence

At the heart of Sisters of the Lost Nation is the complex interaction between supernatural beliefs and the harsh realities of modern-day violence, particularly the epidemic of missing Indigenous women. The rolling head legend, which emerges as a recurring motif, serves as a metaphysical manifestation of the violence and trauma plaguing Anna’s community.

On one level, it is a symbol of unheeded danger and unresolved grief, but it also represents the inescapable presence of past violence that haunts the living. As Anna delves into these supernatural realms, she grapples with a tension between faith in the spiritual world and the stark, brutal realities of human exploitation.

This tension culminates in her actions in Part II, where she uses the lessons from the folklore, particularly the symbolic “hole” in the ground, to take direct action against the forces of violence that have ravaged her community. The story thus suggests that the supernatural and the tangible can coexist and, at times, inform each other.

The spiritual knowledge embedded in Native culture provides not only a means of survival but also a framework for confronting contemporary societal issues, particularly those linked to systemic oppression and violence against Indigenous women.

Critique of Institutional Failures and the Marginalization of Indigenous Voices

Another profound theme in Sisters of the Lost Nation is the critique of institutional failures and the marginalization of Indigenous voices in the face of violence. Throughout the novel, Anna faces bureaucratic indifference and systemic neglect from both tribal and law enforcement authorities in her search for Grace and other missing girls.

The underfunded tribal police, as well as the lack of proper legal infrastructure, make it nearly impossible for Indigenous communities to address the crisis of missing women. The structural neglect is compounded by the wider societal invisibility of Indigenous struggles.

Anna’s own family, as well as the community at large, initially dismiss her concerns, reflecting a broader trend of disempowerment and silence that characterizes Indigenous experiences within modern governance structures. The book highlights how these failures are not just institutional but deeply cultural, as Indigenous voices are often silenced in mainstream discourse.

This theme reaches its poignant apex when Anna, having navigated these institutional barriers, proposes the cultural center as a way to reassert the sovereignty and strength of her people. The center is both a literal and symbolic stand against the forces that have historically ignored and harmed Indigenous communities, providing a space for education, healing, and, most importantly, acknowledgment.

The Transformative Power of Personal Agency in the Fight Against Collective Trauma

The personal transformation of Anna Horn is central to the narrative’s exploration of agency within the context of collective trauma. Initially a teenager burdened with self-doubt and a lack of support, Anna evolves into a fierce advocate for justice, driven by the desire to find her sister and protect her community.

As she navigates the grief of losing Grace and confronts the brutal realities of trafficking, Anna’s growth is both internal and external. Her journey is not just one of seeking answers but also of finding her own voice amidst overwhelming silence and opposition.

By the end of the novel, Anna’s resolve is a testament to the transformative power of personal agency. Her actions—both spiritual and practical—show how individuals can catalyze change, even in the face of insurmountable odds.

Through her, the novel conveys a larger message about the resilience of Indigenous communities and their ability to confront and heal from historical and contemporary wounds. Anna’s shift from passive suffering to active resistance embodies the broader struggle for justice and reclamation that many Indigenous communities face today, transforming trauma into a driving force for collective healing and empowerment.