Stone Blind: Medusa’s Story Summary, Characters and Themes

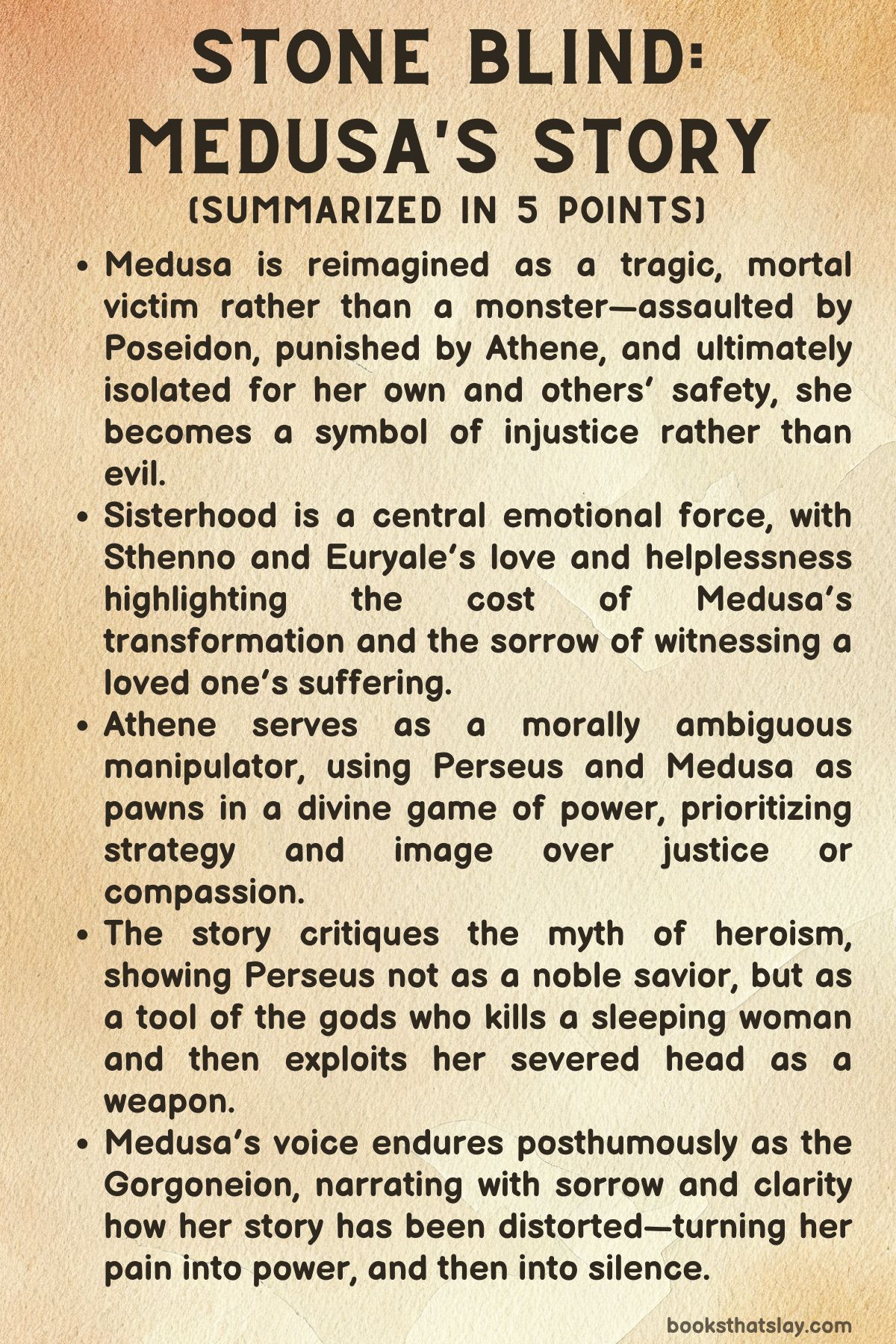

Stone Blind by Natalie Haynes is a fiercely feminist retelling of the Medusa myth that challenges the traditional narrative of heroism, monstrosity, and divine justice.

Through a chorus of mortal, divine, and even inanimate voices, Haynes gives depth and humanity to characters who have long been flattened by myth—particularly Medusa, the so-called monster who was once a vulnerable mortal girl. This novel deconstructs the sanitized versions of ancient stories, revealing the pain, politics, and power struggles beneath. It’s a poignant, poetic, and often darkly funny tale about seeing—who sees, who is seen, and who is allowed to be truly known.

Summary

Haynes reimagines the myth of Medusa with a bold, multi-perspective structure that interrogates themes of power, injustice, and perception.

Divided into five parts—Sister, Mother, Blind, Love, and Stone—the novel builds a layered narrative that spans divine politics, human suffering, and the manipulation of myth.

The story begins in Part One: Sister, where Medusa is introduced not as a monster, but as the only mortal among three Gorgon sisters.

Her sisters, Sthenno and Euryale, are fierce and immortal, but fiercely protective of their youngest sibling. Medusa is raised in love, but her vulnerability sets her apart.

When she is raped by Poseidon in the temple of Athene, it is not the god who is punished but Medusa—Athene transforms her into a Gorgon, her hair turned to snakes, her gaze deadly.

Her sisters’ anguish is palpable as they grieve the loss of her innocence and her human form.

Through divine interludes and poetic reflections, Haynes portrays this transformation not as a descent into monstrosity, but as a brutal act of divine betrayal and a survival mechanism.

In Part Two: Mother, the focus shifts to Danaë, mother of Perseus, and Athene’s long-term manipulation of events to fulfill her divine agenda.

Danaë, imprisoned and impregnated by Zeus, gives birth to Perseus, who is later sent on a quest to slay Medusa. Athene facilitates this, not out of justice or kindness, but as a strategic move. Meanwhile, Medusa’s isolation deepens—she lives blindfolded, afraid of turning even her sisters to stone.

The severed head of Medusa, the Gorgoneion, narrates intermittently, offering bitter commentary on how her legacy is twisted into a symbol of fear and power.

Part Three: Blind chronicles Perseus’s journey. He encounters the Graiai, the Hesperides, and other mythic figures as he gathers the tools needed to kill Medusa. These include a mirrored shield, winged sandals, and the cap of invisibility—all granted or guided by Athene.

Medusa, meanwhile, lives in solitude, hearing only her sisters and feeling the world with heightened non-visual senses. When Perseus arrives, he uses trickery to behead her while she sleeps.

The moment is brutal and quiet; her sisters’ screams echo through the cliffs. Even in death, Medusa is denied dignity. Her head becomes a weapon.

In Part Four: Love, Haynes explores the contradictions of love—familial, romantic, and divine. The narrative moves through Andromeda’s story, as she is chained to a rock to appease a sea monster and “rescued” by Perseus. Yet her chapters show she is unsure whether this rescue is love or possession.

Athene continues to maneuver, placing Medusa’s image on her shield—the aegis—without recognizing the suffering it represents.

Medusa’s snakes even narrate a chapter, underscoring her humanity and the pain of being turned into a symbol. Love in this world is rarely safe or redemptive; it is often transactional, weaponized, or fraught with grief.

Finally, Part Five: Stone brings the story full circle. Perseus uses the Gorgoneion to petrify enemies and even titans like Atlas. Andromeda grapples with her new role as his wife, feeling trapped between obligation and trauma. Danaë reflects on her son’s choices, while the gods continue their games.

The Gorgoneion becomes increasingly bitter, her voice a haunting reminder of the woman erased beneath the myth.

Athene speaks to her only once, failing to acknowledge the harm she enabled. In a powerful closing monologue, the Gorgoneion laments the loss of her story—not her death, but her reduction into a weapon and a warning.

Stone Blind ultimately reclaims Medusa’s voice. It is a defiant act of storytelling that dismantles the mythic architecture built to vilify women and elevate so-called heroes. In this retelling, Medusa is not a monster, but a victim made into one—and even in death, she demands to be seen.

Characters

Medusa

Medusa, at the heart of Natalie Haynes’ reimagined myth, emerges as a deeply tragic and complex character. Her journey from a cherished mortal to a feared and misunderstood monster is shaped by divine cruelty and societal judgment.

Initially depicted as gentle and beloved, Medusa’s transformation into a Gorgon reflects the themes of victimization and the loss of agency. Her transformation is not just physical but also symbolic—her hair becomes snakes, her gaze turns to stone, and she is ostracized, hiding away from the world.

Despite her monstrous appearance and powers, Medusa remains emotionally vulnerable, grieving her lost humanity and the distance from her sisters, whom she loves deeply. The narrative often portrays her internal conflict, her struggle with her new identity, and the lingering memories of the tender person she once was.

Through her eyes, we see the injustice of being punished for a violation, and yet, she does not lose her capacity for love and longing for the warmth of her past life.

Sthenno and Euryale

Medusa’s sisters, Sthenno and Euryale, are also critical to the narrative, representing contrasting emotional responses to the curse that befalls their sibling. Sthenno, immortal and fiercely protective, displays deep grief and a profound sense of helplessness.

She is not only a sister but a guardian figure, mourning Medusa’s transformation while grappling with her inability to protect her. Euryale, who shares her sister’s sense of loss, is torn by guilt and sorrow but also shows strength in her loyalty.

Both sisters embody the love and solidarity between siblings, which is tragically overshadowed by the cruel fate of Medusa. Their emotional struggles highlight the depth of familial bonds, and their helplessness accentuates the larger theme of divine and mortal suffering.

Athene

Athene, the goddess of wisdom and strategy, plays a critical role in the story, embodying the cold and calculating nature of the Olympian gods. Her role in Medusa’s downfall is both pivotal and hypocritical.

She punishes Medusa not for the assault she endures but for the violation of her sanctuary, turning Medusa into a monster. This action exposes the injustices embedded in divine power and the moral blindness of the gods.

Athene’s manipulation continues throughout the story—using Medusa’s head as a tool for her own gain, showing little regard for the human cost. Her character is complex, as she is not just a villain but a representation of divine detachment and the consequences of absolute power.

Athene’s cold intellect contrasts sharply with the emotional turmoil of characters like Medusa and her sisters, offering a critique of the Olympian order where individuals are mere pawns in a larger, indifferent game.

Poseidon

Poseidon’s role in the myth is as both an antagonist and a symbol of unchecked divine power. His assault on Medusa, and his subsequent lack of punishment, stands as a stark commentary on the differential treatment of mortals and gods.

His interactions with Amphitrite, his wife, introduce a layer of complexity to his character, showing a tension between his public persona as a god of the sea and his private relationships. While Poseidon is portrayed as the immediate perpetrator of Medusa’s tragic transformation, the focus is less on him as an individual and more on the broader critique of the divine world that permits such acts without consequences.

Danaë

Danaë, Perseus’s mother, is another pivotal character in the novel, representing maternal love, strength, and sacrifice. Imprisoned by her father due to a prophecy, Danaë’s narrative intersects with the broader themes of fate and powerlessness.

Despite being a victim of divine intervention—first through her confinement and later through Zeus’s visit in the form of golden rain—Danaë remains a symbol of resilience. She loves her son, Perseus, unconditionally, even as she recognizes the limits of her ability to protect him.

Her grief over her lack of control in shaping his future speaks to the overarching themes of fate versus free will, and the constraints placed on mothers in a world dominated by powerful men and gods.

Andromeda

Andromeda is introduced as the beautiful, sacrificial daughter of Cassiopeia. Her narrative embodies the dichotomy of beauty as both a blessing and a curse.

She is bound to a rock, a symbol of both her victimhood and the expectation of her rescue by a hero. However, her feelings about being saved by Perseus are complex—she questions whether her rescue is truly an act of love or simply the fulfillment of divine plans.

Andromeda’s arc explores the trauma of being reduced to a passive object of desire, with her worth often defined by others’ perceptions of her beauty and utility in fulfilling a heroic narrative. Her struggle to find autonomy in the wake of Perseus’s actions emphasizes the theme of women’s agency within mythological frameworks.

Cassiopeia

Cassiopeia, the queen of Ethiopia and Andromeda’s mother, plays a more subtle role in the novel but is crucial in setting the stage for her daughter’s fate. Her vanity, symbolized by the mirror given to her by her husband, ultimately leads to divine retribution.

Cassiopeia’s prideful declaration that her daughter is more beautiful than the Nereids angers the gods, and her actions have far-reaching consequences for Andromeda. Her character is emblematic of the consequences of hubris in Greek mythology, where the gods often punish those who overstep their bounds.

Her vanity leads to the sacrificial fate of her daughter, reinforcing the novel’s critique of divine power and the burdens placed on women in mythological stories.

Amphitrite

Amphitrite, Poseidon’s wife, adds another layer of complexity to the mythological narrative. Her role as a goddess who observes her husband’s actions, particularly his assault on Medusa, introduces the theme of marital loyalty and the internal conflict faced by women in relationships with powerful gods.

Amphitrite’s emotional struggle reflects the broader theme of female agency—or the lack thereof—in a world where divine male power shapes the lives of mortal and immortal women alike. Her sorrow and bitterness reveal the limitations placed on her autonomy, despite her own divine power.

Themes

Complexities of Gender and Divine Power Dynamics

In Stone Blind, one of the epic themes is the manipulation of gender and the abuse of power by the divine. Throughout the novel, the gods, particularly the male figures, wield immense power over the mortal and divine realms.

Medusa’s transformation into a monster is not only a punishment for a transgression she did not choose but also an example of the way in which gods manipulate mortal lives for their own agendas. In this retelling, the gods’ actions reflect their detached nature, showing how their divine privileges lead to horrific consequences for those who have no control over their fates.

Poseidon’s assault on Medusa, for instance, is treated not with justice but as an opportunity for Athene to assert her power by punishing Medusa instead. This reveals how divine power is wielded without accountability.

This theme extends beyond Medusa, as seen in characters like Danaë, whose life is dictated by malevolent divine forces, and Andromeda, whose beauty becomes a curse. The narrative explores how women’s fates are shaped and destroyed by the decisions of male gods, showing the vulnerability and helplessness that arise when divine power is placed in the hands of those who seek to control and exploit.

Sisterhood as a Source of Emotional Strength and Tragic Support

A central theme in Stone Blind is the exploration of sisterhood, which provides emotional depth to Medusa’s story. The Gorgon sisters—Medusa, Sthenno, and Euryale—are depicted as beings capable of immense love, empathy, and sacrifice, yet they are tragically powerless in the face of divine cruelty.

Their bond, however, remains a source of emotional strength, particularly for Medusa. The transformation of Medusa into a stone-turning monster does not erase the deep care and affection her sisters have for her.

In fact, their reactions highlight the complexity of love amidst overwhelming tragedy. Sthenno’s protective instincts and Euryale’s helpless grief reveal the intensity of the love that exists even within monstrous forms.

Yet, this love cannot shield Medusa from the violence inflicted upon her by the gods. The sisters’ emotional support for one another becomes a poignant counterpoint to the divine forces that relentlessly tear them apart, underscoring the tragic nature of their lives.

Sisterhood in this context is not just a source of resilience but also a bitter reminder of how love and familial bonds are often overshadowed by fate and divine retribution.

The Dehumanization of Medusa and the Destruction of Identity

Medusa’s journey in Stone Blind is a deep exploration of the dehumanization of women and the destruction of personal identity at the hands of those in power. Once a beautiful and beloved mortal, Medusa is transformed into a monster, her humanity stripped away, and her identity reduced to that of a weapon—an object of fear and punishment.

This theme is highlighted in the stark contrast between her past as a cherished individual and her present as a grotesque figure whose gaze turns all to stone. The loss of Medusa’s humanity is not just physical but psychological; she grapples with the emotional and existential impact of her transformation.

The novel critiques how society, both divine and mortal, takes away the humanity of those who deviate from expected norms, especially when women are involved. Medusa’s metamorphosis into a monster is symbolic of how women’s identities can be reshaped and destroyed by others’ perceptions and societal norms.

Her transformation serves as a reflection of how patriarchal systems disempower women by reducing them to symbols of terror or sacrifice, erasing their complex humanity and narrative agency.

The Role of Memory and the Shaping of Mythological Narratives

A key theme explored in Stone Blind is the role of memory and the ways in which mythological narratives are constructed and distorted over time. Medusa’s severed head, the Gorgoneion, acts as a narrator throughout the novel, reflecting on how her story is reinterpreted and weaponized by others.

The Gorgoneion, as a literal and metaphorical object, bears witness to the rewriting of her story by those who seek to reshape it to fit their own needs. As Medusa’s image becomes an emblem of both fear and power, her true story—the trauma, the betrayal, and the complex emotional life she led—becomes obscured by the mythic lens through which it is viewed.

This theme underscores how myths evolve, often to serve the interests of those in power, and how the true essence of an individual’s experiences can be erased or distorted in the process. Medusa’s reflections as the Gorgoneion show the tension between the lived reality of an individual and the way society chooses to remember and mythologize them.

The novel offers a poignant commentary on the destruction of personal narratives in favor of dominant, often exploitative, stories.

The Intersection of Love, Sacrifice, and Subjugation

Love, in its many forms, is explored in Stone Blind as a complex, often contradictory force that intertwines with sacrifice and subjugation. Throughout the novel, love is portrayed not as a simple redemptive force, but as something that can be coercive, destructive, and deeply entangled with the suffering of those involved.

Medusa’s tragic fate is largely shaped by love: from her ill-fated attraction to Poseidon to her sisters’ unwavering devotion to her, love is both a source of strength and a cause of immense pain. The portrayal of love in the novel also critiques how love is often used to justify control and manipulation.

Characters like Athene and Perseus show how love, when viewed through the lens of divine power, can lead to the subjugation of others. The story contrasts different forms of love—romantic love, familial love, and love born of duty—and how each can lead to sacrifice and suffering.

The narrative ultimately challenges conventional ideals of love, suggesting that in the world of the gods, love is not a redemptive force but one that often leads to subjugation, erasure, and the sacrifice of individual agency.

The Power and Tragedy of Transformation

The theme of transformation is central to Stone Blind, and it is explored both in terms of literal physical changes and metaphorical shifts in identity. Medusa’s transformation from a beautiful mortal into a monster is the most obvious manifestation of this theme, but the novel also explores other forms of transformation, including the ways in which people and gods change due to circumstances beyond their control.

Medusa’s metamorphosis is not just a punishment; it is a profound and tragic change that affects her very being. Her transformation reflects the broader theme of how identity can be shaped by external forces and the loss of control one experiences when subjected to the whims of more powerful beings.

The novel juxtaposes physical transformations with emotional and psychological shifts, highlighting how these changes often carry with them a loss of agency and autonomy. Through Medusa’s story, the novel critiques how transformation is often imposed as a means of punishment, subjugation, or control, turning the act of changing into something that erases one’s past and future possibilities.