Good Dirt by Charmaine Wilkerson Summary, Characters and Themes

Good Dirt by Charmaine Wilkerson is a deeply layered novel that spans continents, generations, and emotional landscapes.

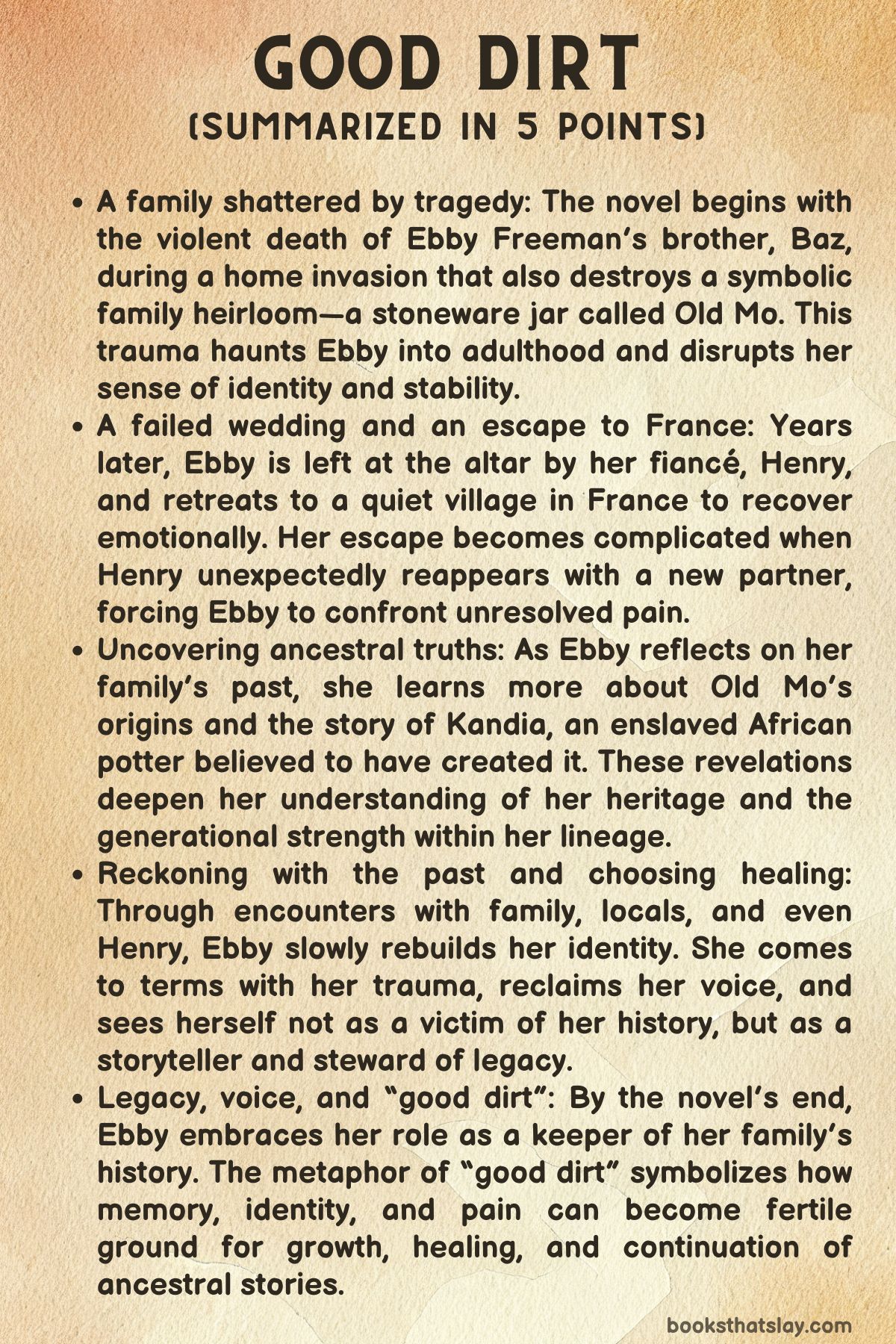

At its heart is Ebby Freeman, a Black American woman whose life is shaped by trauma, silence, and heritage. After the tragic loss of her brother and the collapse of her wedding, she retreats to rural France, only to confront the ghosts she thought she had escaped. Through the shattered pieces of a historic family heirloom—Old Mo, a handmade jar—Ebby embarks on a journey of personal and ancestral healing. Wilkerson masterfully blends family saga with cultural reckoning, crafting a tale of memory, resilience, and reclamation.

Summary

Charmaine Wilkerson’s Good Dirt tells the multi-generational story of Ebby Freeman, a woman whose life is fractured by a tragic past but ultimately redefined by a journey toward healing and self-understanding.

The story is structured in four parts, beginning with a brutal act of violence that permanently alters the trajectory of her family’s legacy.

As a child, Ebby witnesses the murder of her beloved older brother Baz during a home invasion at their family estate in Connecticut. In the same moment, a cherished family heirloom—Old Mo, a stoneware jar tied to their African American heritage—is destroyed.

This moment is not only traumatic, but symbolic: it marks the literal and emotional shattering of family continuity.

Years later, Ebby is again devastated when her wedding is abruptly called off; her fiancé, Henry, disappears without explanation, pushing her further into emotional isolation.

Seeking escape, Ebby relocates to a quiet French village to manage a friend’s guesthouse. She longs for anonymity and solitude. But fate intervenes—Henry arrives at the property as a guest, accompanied by his new partner, Avery. This unexpected reunion forces Ebby to confront the very wounds she tried to leave behind.

The tension with Henry is complicated by Avery, who turns out to be intelligent, insightful, and more than a romantic rival; she is a mirror, showing Ebby new truths about herself.

As the narrative shifts between present-day France and flashbacks to her family’s past, readers learn more about the origins of Old Mo.

The jar is believed to have been crafted by Kandia, an enslaved African potter, whose artistic spirit and resilience ripple through generations.

The novel delves into Ebby’s lineage, revealing a complex, often painful history shaped by migration, memory, and silence.

In France, Ebby starts to reconnect with that legacy—through quiet routines, community interactions, and conversations with Henry that no longer revolve around romance, but rather around clarity, accountability, and release.

In Part Three, Ebby receives mysterious phone calls from a man named Robert, who is connected to the Freeman family in unexpected ways.

His revelations lead Ebby to unearth forgotten parts of her ancestry and understand the fuller significance of Old Mo—not just as a family relic, but as a vessel of stories, endurance, and cultural artistry.

Her ancestors’ sacrifices, especially those of the Freeman women and Kandia, begin to take central emotional weight.

Part Four brings everything full circle. Ebby finally speaks honestly with her mother, Soh, breaking long-held silences and uncovering maternal truths that had been buried for decades.

The emotional reunion is healing and allows Ebby to accept the burdens—and the gifts—of her lineage.

A family emergency calls her back toward home, both literally and metaphorically, prompting her to re-evaluate what “home” truly means.

Though the jar was shattered, its spiritual restoration is realized through Ebby herself. She becomes a living vessel for its story. Instead of fleeing from her past, she leans into it—writing, remembering, and reclaiming. Henry fades from her life, not out of bitterness, but through a graceful letting go.

The true inheritance isn’t the jar itself, but the legacy it represents: creativity, survival, and the richness of Black heritage.

In the final pages, Ebby stands rooted—not just in France, not just in her past, but in purpose. She becomes the keeper of stories, the cultivator of “good dirt”—the kind in which healing, memory, and future can grow.

Characters

Ebby Freeman

Ebby Freeman is the central character of Good Dirt, and her journey is one of emotional healing and self-discovery. At the heart of her character is the trauma she experiences following her brother Baz’s death and the destruction of the Freeman family heirloom, a jar named Old Mo.

Throughout the novel, we witness Ebby grappling with grief, loss, and a fractured sense of identity. In the beginning, she is deeply scarred by her family’s past, particularly the murder of Baz, and the breakdown of her engagement to Henry further compounds her emotional turmoil.

However, as the story progresses, Ebby’s character evolves from someone who is consumed by pain to a woman who begins to reclaim her own narrative. Her decision to move to France in search of solace symbolizes her retreat from her past, but it is also a place where she confronts unresolved emotions and finds strength in her heritage.

Ebby’s emotional journey is not about returning to normalcy but about rebuilding herself through reflection, writing, and confronting the legacies of trauma that have shaped her life.

Henry

Henry plays a significant, though complex, role in Ebby’s life. Initially, he is introduced as Ebby’s ex-fiancé, the man who abandoned her at the altar, a traumatic act that deepens her sense of abandonment and loss.

However, as the narrative unfolds, Henry’s character is revealed in more nuanced layers. His reappearance in France with his new partner Avery forces Ebby to confront not only her past with him but also the unresolved feelings she has regarding their failed relationship.

Henry is portrayed with emotional complexity, as he seeks redemption and attempts to explain his actions to Ebby. While his character does not undergo a typical redemption arc, his presence serves as a vehicle for Ebby’s personal growth.

He embodies themes of guilt, betrayal, and the struggle for emotional honesty, but ultimately, his role in Ebby’s life is one of closure rather than reconciliation.

Avery

Avery is initially introduced as the “other woman,” the person with whom Henry is now involved. However, as the novel progresses, Avery is shown to be much more than just a rival. She is a woman with her own ambitions, insecurities, and complexities.

Her interactions with Ebby are initially marked by tension, but over time, she reveals a more empathetic side. Avery’s relationship with Henry, though seemingly a point of competition for Ebby, evolves into a source of introspection for both women.

Avery’s presence forces Ebby to reflect on her own life, and by the end of the story, Avery is no longer just an adversary but a woman who has her own struggles, making her a more sympathetic character. Her role in the novel highlights the dynamics of race, class, and ambition, and through her, the reader gains a deeper understanding of the pressures women face in their personal and professional lives.

Soh Freeman

Soh Freeman, Ebby’s mother, plays a pivotal role in Part Four of the novel. Her relationship with Ebby is initially marked by silence and emotional distance, a reflection of the unspoken pain and generational trauma that both women carry.

Soh’s character becomes more fully realized in the later parts of the novel, where she begins to open up about her own past, her struggles as a Black woman in America, and the painful silences within their family. Through Soh’s revelations, Ebby gains a clearer understanding of her own identity and the shared pain they both carry.

Soh’s presence in the narrative is crucial to Ebby’s final emotional reckoning, as the two women reconcile their differences and come to terms with their collective history. Soh embodies themes of motherhood, sacrifice, and the weight of unspoken truths, and her relationship with Ebby is one of healing and mutual understanding.

Kandia

Kandia, the African potter whose legacy is central to the story of Old Mo, is a symbolic figure whose presence resonates throughout the novel. Though not a direct character in the conventional sense, Kandia’s story is interwoven with the Freeman family’s history, and his life as an enslaved person and potter becomes a cornerstone of the narrative.

His craft and legacy are embodied in the jar Old Mo, which symbolizes not just the family’s past but the enduring strength and creativity of those who came before. Kandia’s story is one of survival, resilience, and the connection between art and identity.

As Ebby uncovers more about Kandia’s life and his connection to her family, she begins to understand that her heritage is not just one of privilege or tragedy but also one of artistic and cultural endurance. Kandia’s influence is felt as Ebby reclaims her own voice and heritage, seeing herself as both a survivor and a protector of this legacy.

Robert

Robert’s role in Good Dirt is pivotal in the latter part of the novel, as he becomes the key to unlocking family secrets and the true connection between Ebby’s family and Kandia’s lineage. His relationship to the Freeman family is complex and filled with emotional weight.

As the person who contacts Ebby and provides information about her ancestors, Robert helps to bridge the gap between the present and the past, guiding Ebby toward a deeper understanding of her heritage. His revelations about the jar and its history serve as a turning point for Ebby, allowing her to see her family’s legacy in a new light.

Robert’s character represents the intersection of memory, history, and the ongoing search for truth. Through his involvement, Ebby gains the clarity she needs to reclaim her role as a storyteller and keeper of her family’s legacy.

Themes

Intergenerational Trauma and Memory

A central and profound theme in Good Dirt is the exploration of intergenerational trauma and how the legacies of the past are carried through memory, objects, and personal identities. The narrative not only addresses the immediate trauma experienced by Ebby after the violent death of her brother Baz but also delves deeply into the ancestral history that shapes her sense of self.

The jar, Old Mo, serves as a powerful symbol of this legacy. It represents the physical and emotional scars passed down through generations, particularly through the lens of the African American experience.

The potter Kandia’s story—the tale of his kidnapping and forced labor—becomes a pivotal link to understanding how past injustices reverberate through the present. This exploration highlights the tension between trying to escape the weight of historical trauma and the need to reckon with it in order to move forward.

As Ebby confronts her personal grief, the narrative reveals that healing is not a linear process, but rather a complex journey shaped by both family history and individual reckoning.

Cultural Identity and Legacy

The theme of cultural identity and the complexities of heritage plays a crucial role throughout the novel. The Freeman family is not only defined by its social status and history but also by its artistic and cultural inheritance.

The significance of Old Mo, a family heirloom made by an enslaved African potter, underscores the importance of connecting with one’s roots, particularly when those roots are buried beneath centuries of oppression and displacement.

For Ebby, this journey of self-discovery is inextricably linked to her relationship with the jar and the history it encapsulates. The novel beautifully intertwines the personal with the historical, urging Ebby to reclaim her narrative and to recognize her role as the custodian of her family’s story.

This theme highlights the idea that understanding one’s past—especially the difficult and painful parts—can be a means of empowerment, allowing individuals to shape their own identity and legacy.

Healing through Storytelling and Writing

Storytelling, particularly through the act of writing, is portrayed as a tool for healing and reclaiming personal agency. Ebby’s writing becomes a transformative act that allows her to process her trauma and make sense of her fractured identity.

The novel positions writing not just as a personal escape, but as a communal act of preserving history and culture. Through her writing, Ebby takes control of the narrative that has been defined by loss, betrayal, and public tragedy.

As she reconnects with her family’s past, she realizes that storytelling is her most powerful tool for survival and for keeping her ancestors’ legacies alive. This act of storytelling ultimately allows Ebby to find her voice, not as a passive recipient of trauma, but as an active creator of her future.

The theme of writing as reclamation is not just about telling a story, but about reshaping one’s life and connecting with the broader cultural and familial currents that define a person’s existence.

Reconciliation and Personal Growth

Another significant theme in Good Dirt is the idea of reconciliation—not just with others, but with oneself. Ebby’s journey toward healing involves confronting painful truths, letting go of old wounds, and ultimately making peace with her past.

Her interactions with Henry, her ex-fiancé, reveal the complexities of forgiveness and the difficulty of reconciling past love and betrayal. However, the resolution of their relationship does not follow a conventional arc of romantic reunion.

Instead, Ebby achieves closure through emotional maturity and self-acceptance, realizing that true healing does not depend on others, but on her ability to reclaim her own sense of agency.

Similarly, her relationship with her mother, Soh, evolves from one of silence and distance to one of understanding and shared vulnerability. This emotional reconciliation, grounded in familial love and understanding, highlights the importance of confronting difficult histories and embracing the messy, imperfect process of personal growth.

The Role of Place and Belonging

The theme of place is intricately woven into the narrative, with the rural French village serving as both a literal and metaphorical space for Ebby’s emotional and spiritual healing. Moving away from the familiar confines of Connecticut allows Ebby to escape the public eye and the weight of her family’s expectations.

Yet, the novel reveals that true belonging is not tied to geography or social status, but to a deeper connection with one’s roots and personal truths. The village becomes a crucible for Ebby’s internal transformation, where she not only redefines her sense of self but also begins to understand the broader significance of her family’s history and legacy.

Ultimately, Ebby’s journey is one of finding home—not in a specific place, but in the recognition of her own identity, her roots, and the power she holds to shape her own future.

Resilience and Reclamation of Power

The overarching theme in Good Dirt is one of resilience—the ability to confront loss, trauma, and injustice, and still find a way to move forward. Ebby’s journey is marked by moments of despair, but ultimately, it is a testament to the strength of the human spirit and the possibility of reclamation.

The metaphor of good dirt—earthy, imperfect, and full of generational richness—captures the essence of this theme. The soil, like the characters, is not pristine; it has been disturbed, cultivated, and transformed over time, but it remains fertile and capable of growth.

In reclaiming her family’s story, her voice, and her identity, Ebby embraces her power to shape her own legacy. This theme reinforces the idea that, despite the ruptures caused by trauma, there is always potential for repair, renewal, and the creation of something meaningful from the brokenness.