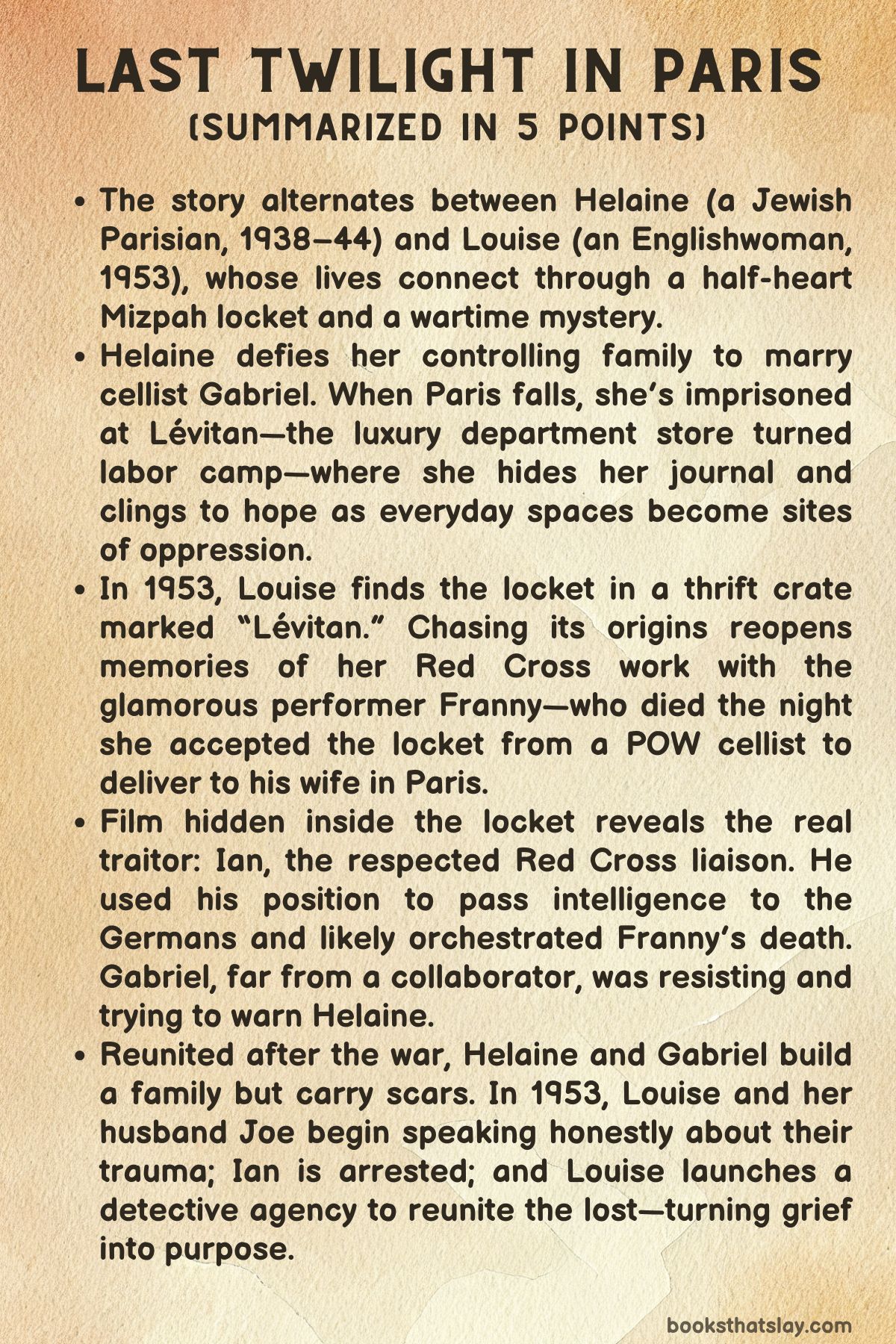

Last Twilight in Paris Summary, Characters and Themes

Last Twilight in Paris by Pam Jenoff is a historical novel that interlaces two women’s lives across different decades, both connected by a single mysterious necklace.

Set against the turbulent backdrops of Nazi-occupied Paris and postwar England, the novel explores the resilience of love, identity, and truth in times of darkness. Through Helaine, a young Jewish woman fighting to survive in wartime Paris, and Louise, a postwar Englishwoman haunted by secrets of the past, Jenoff paints a portrait of sacrifice and redemption. The story examines how courage takes many forms—sometimes in defiance, sometimes in endurance, and sometimes simply in remembering.

Summary

In prewar Paris, Helaine Weil has grown up in a gilded cage after childhood illness leaves her fragile and tightly supervised by her elegant mother, Annette, and her frequently absent father, Otto. Allowed short walks at last, she hears a cellist practicing and meets Gabriel Lemarque. The connection is immediate: he treats her as a whole person rather than a patient.

Their romance accelerates; despite her parents’ outrage and fears about her health and future, Helaine chooses Gabriel, slipping out with a half-heart necklace once given by her grandmother. They marry, living modestly yet content as Europe darkens.

With occupation, antisemitism that once hid in glances becomes law. Gabriel keeps playing to keep them fed, then resists in small ways that endanger his job; one evening Helaine is ejected from the symphony hall because she is Jewish. He fights the humiliation but returns to the stage for their survival. As restrictions sharpen—star badges, limited markets—Helaine clings to purpose in a community garden. Rumors swirl that Gabriel has been pressed into a German-approved tour; he hints that complying may shield Helaine.

Before leaving he takes the other half of the heart, a private promise that they’ll find each other.

A year later, Helaine’s world contracts again. Seeking news, she confronts officials and is seized as the wife of an enemy of the Reich. She is sent not to Drancy but to Lévitan, the former luxury department store repurposed as a camp where Jews sort plunder for German buyers. Lévitan has a hierarchy and rules; punishment for one is punishment for all. Helaine learns to survive, hides her locket in a wall, and marks the days in secret.

She befriends Miriam, who smuggles tiny acts of sabotage into the system and warns Helaine about Maxim, a predatory French guard. When Helaine spots her grandmother’s tea set among the loot, she understands her mother has been taken. The city that once promised freedom has become a map of traps.

In England, years later, Louise Keene is a capable woman starved for purpose. Her marriage to Joe is tender yet hindered by what neither has said about the war. At the thrift shop where she works, she finds a gold half-heart engraved with “watch” and “me,” a Mizpah charm once given to loved ones parted by distance.

The trinket ignites memories: in 1944 she’d volunteered with the Red Cross, crossing to the Continent with Ian Shipley, principled and magnetic, and Franny Beck, a celebrated performer who used her access to POW camps for more than morale. Franny posed for photos with prisoners to create identities for escape—and once, Louise saw Franny accept something small from a French cellist.

Now Louise seeks answers. The crate that held the necklace is stamped Lévitan, a name that means little to people in 1953 but everything to those who remember. In Paris she learns Lévitan housed Jewish prisoners forced to sell confiscated goods. An elderly neighbor points her to Henri Brandon, a survivor who recalls a fellow inmate married to a cellist named Gabriel Lemarque.

Louise has the sickening realization that the locket may have been intended for a woman inside that store. She also finds a sliver of undeveloped film hidden inside the locket and sends it out, unsure what it holds.

Back in 1943–44, Helaine’s path crosses Gabriel’s once more. Bribes and contacts buy him a brief visit into Lévitan. He assures her he is no collaborator; he has been using his position to pass information for the resistance. He urges patience and caution, and they cling to each other.

Later, Helaine is moved onto the shop floor among German officers who treat the prisoners as invisible staff. She overhears talk that musicians—including a cellist—have been transferred to a POW camp.

As Allied forces approach Normandy, panic ripples through Paris. Miriam warns that guards will eliminate witnesses before retreating. Helaine and Miriam plot escape, are caught once, then are shoved onto a bus during a sudden evacuation. At a traffic halt, Helaine yanks the bell cord, yells, and runs. Miriam is seized and, with a last wave, sacrifices her chance so Helaine can flee.

Helaine hides for days until liberation rolls in on tank treads. Relief is complicated by grief: records confirm her mother’s death; news from a burned camp suggests Gabriel has perished. Sick yet determined, Helaine writes to steady herself—then learns she is pregnant. On a Paris street she hears a melody Gabriel composed for her and, following the sound, finds him alive. They rebuild, and to honor her family’s losses, he takes Helaine’s surname.

In 1953 Paris, Louise breaks into an old dormitory room at Lévitan and discovers a leather journal tucked inside the wall, marked with the name Helaine Weil Lemarque and a sketch of a half-heart locket.

The clue leads her to a G. Weil in the phone book. At the apartment door, Helaine answers. Louise returns the journal; Helaine produces her half of the locket. Joe arrives from England, ready to help rather than hold Louise back. Gabriel joins them, and pieces slide into place.

The developed film shows a civilian passing an envelope to a German officer during a camp visit. Louise recognizes the civilian: Ian Shipley. Gabriel explains that while performing he learned a traitor inside Allied circles was trading secrets using Red Cross cover. When Franny visited, Gabriel saw a chance to move the locket—with film evidence inside—toward Helaine. Franny accepted it, then unknowingly asked Ian himself to help deliver it.

Shortly after, she died in a supposed hit-and-run that left no convincing injuries. Gabriel believes Ian orchestrated her death and the locket’s disappearance. A musician friend likely salvaged the necklace from Franny’s things and later sent it to Lévitan, where it vanished into the tide of goods until it resurfaced years later in England.

Confronted with the image, Louise reports Ian. Authorities arrest him; the necklace is recovered among his effects and sent to Helaine. The revelations loosen the knot in Louise’s marriage: she and Joe begin to speak plainly about the past; he seeks help for his war scars; she starts a small agency to reunite families and pursue missing threads. Helaine, still marked by Lévitan, begins to imagine telling her story in full. Gabriel asks Louise to search for his youngest sister; Helaine asks for help finding her father.

The two women—one who endured the occupation from inside its stolen rooms, one who returns a decade later to face what she could not—have, through a locket and a journal, brought the hidden history inside Last Twilight in Paris into the light.

Characters

Helaine Weil Lemarque

In Last Twilight in Paris, Helaine’s arc moves from enclosure to agency, tracing a sheltered young woman whose ill health and overprotection create a hunger for life that becomes the engine of her choices.

Early on, confinement teaches her to live inwardly—through books, dreams, and a writer’s imagination—but it also sharpens her sense of what freedom means when she finally steps outside and meets Gabriel.

Her marriage is an act of self-definition rather than rebellion for its own sake; she knowingly accepts a precarious future because it promises personhood. Occupation-era Paris forces her to recalibrate courage: the humiliation of exclusion, the predation at Lévitan, and the constant calculation of risk mature her from romantic idealist to pragmatic survivor without extinguishing her tenderness.

The necklace becomes her portable covenant—half a promise to love, half a command to endure—and the journal she hides in the dormitory wall reveals a mind intent on making meaning out of suffering. Even after liberation, she is not released from memory; motherhood offers renewal, but trauma lingers as a shadow vocabulary beneath ordinary days.

Helaine’s final stance—choosing to write her own story and to help others find the missing—makes resilience communal rather than solitary, turning survival into a form of stewardship.

Louise

Louise enters the 1953 frame story restless, resentful of domestic smallness and the silence she and Joe have allowed to calcify around their wartime pasts. The thrift-shop discovery of the Mizpah necklace becomes the catalyst that reunites her with her wartime self—capable, morally inquisitive, and unafraid to push authority. In her 1944 memories, she is both brave and humanly limited: she refuses Franny’s plea out of fear, then lives with the ache of that refusal.

The Paris investigation lets her do what she could not do then—ask hard questions without permission, follow threads others dismiss, and refuse the false comfort of not knowing. Louise’s most important transformation is relational. She learns that secrecy corrodes intimacy more reliably than pain does, and that partnership requires narrating one’s own brokenness.

Founding a detective agency is not a flight from family; it is the professional expression of her deepest wartime competence—witnessing, connecting, and bringing hidden truths into daylight.

Gabriel Lemarque

Gabriel is written as a man of art pressed into the ethics of ambiguity. His love for Helaine is ardent and immediate, but it matures into a strategic devotion when survival demands compromise.

Refusing to play for propaganda costs him, yet performing when necessary is not capitulation so much as cover for resistance activities and protection for his Jewish wife. The limp he bears and the cello he plays both symbolize imperfect beauty: woundedness that does not preclude grace.

His decision to send the necklace with evidence against the traitor reveals a mind that frames love as responsibility; he will risk reputation and even family to safeguard truth. Postwar, taking Helaine’s surname signals a reversal of the usual assimilation logic—rather than absorbing her into his identity, he honors her lineage and grief by joining it. Gabriel’s arc shows how integrity can survive in pieces, held together by loyalty rather than by spotless record.

Ian Shipley

Ian embodies the story’s most chilling betrayal: the trusted humanitarian who weaponizes access. In the 1940s timeline, he presents as disciplined, principled, even attractive in his restraint; he polices the boundaries of Red Cross protocol, claiming that obeying the rules enables the greatest good.

That rhetoric masks self-interest and treason. His refusal to help deliver the necklace is not cautious prudence but strategic control, and his intimacy with Louise—brief, secretive—echoes his larger pattern of crossing lines only when it serves him.

The 1953 exposure of the film reframes his past: he did not simply fail to act; he acted decisively against the vulnerable people who trusted him. Ian’s character warns that respectability and proximity to power can camouflage moral rot, and that institutions meant for mercy can be infiltrated by those who despise accountability.

Franny Beck

Franny is the bright flare whose brief presence alters several lives. A celebrity willing to sing for both sides to reach prisoners, she treats performance as surveillance and care: the photographs she takes are not souvenirs but instruments for escape, and her public smile conceals quiet, daring labor.

She also bears scars—exploitation at home, the precariousness of a queer woman moving through predatory spaces—and yet she keeps choosing visibility for others’ sake. Her fatal night is a hinge of guilt for Louise and a pivot for the plot’s mystery, but thematically Franny represents witness under occupation: the artist who refuses to be merely ornamental. Her death is not a random tragedy; it is the cost extracted by treachery when courage becomes inconvenient.

Joe

Joe initially appears as the emblem of postwar drift—anxious, drinking, and silently haunted—yet the Paris trip reveals a sturdier core.

His early insistence on routine is not small-mindedness so much as fear that revisiting the war will shatter the fragile life he and Louise have built. When he follows her to Paris, he chooses partnership over pride, takes on the parenting load she usually carries, and listens without defensiveness. Joe’s arc reframes masculinity in recovery: strength as openness to therapy, love as the willingness to be changed by a spouse’s truth.

By encouraging Louise’s new vocation, he helps transform her restlessness into purpose, and their marriage moves from coexistence to collaboration.

Miriam

Miriam is Helaine’s moral and practical tutor inside Lévitan. She has seen Drancy; she knows that survival requires both solidarity and subterfuge.

Through sabotage, smuggling, and hard-earned rules about safety, she teaches Helaine how to resist without martyrdom. Her proposed escape is realistic rather than romantic, and when the evacuation comes, her last wave to Helaine is both blessing and command: live so someone can tell what happened.

Miriam’s legacy in the novel is the discipline of hope—planning, bartering, and protecting one another in the teeth of despair.

Annette Weil

Annette’s love takes the form of confinement, a choice forged by years of nursing a fragile child and by the class expectations of a Parisian household that prized appearances. She is both caretaker and jailer, and that contradiction haunts her relationship with Helaine.

Her hesitation to break with Otto, her absence during Helaine’s persecution, and her ultimate deportation traced through the tea set reveal a woman trapped by roles she also enforces. Annette’s tragedy is that devotion without trust can become a cage; her memory survives in heirlooms and in the surname Helaine preserves.

Otto Weil

Otto is a study in authority that mistakes control for protection. His fury at Gabriel is less about religion or class than about losing the narrative of his family. He travels, keeps a lover, and expects domestic order to persist in his absence.

The occupation exposes the limits of such command; wealth and connections cannot guarantee safety, and his distance leaves others to absorb the consequences. Otto’s presence is felt most strongly through absence—through the precariousness his choices create and the silence that follows.

Isa

Isa embodies ordinary courage. A mother growing food in a city that has forgotten how to be kind, she befriends Helaine because proximity demands it. When the garden is closed to Jews, she chooses her children’s survival without abandoning compassion; later she risks herself to bring news, food, and Helaine’s journal, and she gets word to Gabriel. Isa’s decisions illustrate the novel’s insistence that heroism often looks like errands, like passing a message, like refusing to let fear dehumanize a neighbor.

Maxim

Maxim personifies collaboration’s petty predation. He is not a grand ideologue; he is an opportunist who leverages his small authority to threaten and to extract. His oily offers of help, his fixation on catching escapees, and his eagerness to police the women’s movements show how occupation empowers the mediocre to become dangerous. Maxim reminds us that systems of oppression are built not only by architects but by clerks and guards who enjoy being obeyed.

Midge

Midge appears in 1953 as a catalyst rather than a confidante. Her thrift shop becomes the portal through which the past interrupts Louise’s present, and her practical connections—like the sister’s jewelry expertise—validate the necklace’s significance. She represents postwar Britain’s network of older women who keep communities stitched together with gossip, goods, and quiet competence, enabling younger women like Louise to rediscover vocation.

Henri Brandon and Celeste

Henri and Celeste serve as guardians of memory in Paris. Celeste insists that a rebuilt city must still answer questions about what stood there before; Henri, a former prisoner, supplies the connective tissue between the necklace, Lévitan, and Gabriel. Together they embody civic remembrance, demonstrating how personal testimony resists the erasure that bureaucratic records attempt to perform.

Ewen and Phaedra

Louise’s children function less as developed characters than as moral stakes. Their sheltered innocence measures the distance between wartime terror and 1950s normalcy, and their presence sharpens Louise’s fear of reopening old wounds while ultimately reminding her that truth-telling is a parental gift. In choosing investigation and candor, Louise models for them a future in which love is honest even when it is painful.

Themes

Moral choice under occupation

From the first separation line in occupied Paris to the last reckoning in London and Paris a decade later, moral choice never arrives cleanly labeled. The story insists that survival, loyalty, and courage are braided with fear, bargaining, and small capitulations. Gabriel refuses to play for an audience that excludes his wife, yet accepts later engagements that keep them fed and, he hopes, protected. Helaine sabotages stolen goods at Lévitan, then risks the entire workshop by carrying contraband to the loading dock because solidarity makes refusing unthinkable.

Isa keeps tending the victory garden after Jews are barred, a decision that comforts and condemns in equal parts: her children eat because she keeps working; Helaine starves at the fence. Ian, the humanitarian face of the Red Cross, performs triage as an ethic, limiting what he will risk for any one prisoner so he can continue helping many—until we discover he has been bending that calculus toward treachery.

These choices generate consequences that cannot be neatly sorted into heroism or villainy. Even acts that look noble—Gabriel’s visits, Helaine’s defiance on the bus—carry danger for bystanders who may pay with beatings, lost rations, or execution. Last Twilight in Paris frames resistance not as a static identity but as a moving target shaped by hunger, surveillance, and the power of others to punish.

The novel’s most harrowing argument is that under occupation, every path is compromised: refusing corrupts because it imperils the vulnerable; complying corrupts because it sustains the regime.

The ethic that remains, then, is an ethic of responsibility to specific people at specific moments—spouses, fellow prisoners, unknown POWs behind wire—chosen again and again in circumstances where choosing is itself a kind of danger.

Civilian spaces turned into instruments of control

The book maps a city’s slow transformation from everyday backdrop to apparatus of oppression. The Paris sidewalks that once carried Helaine to music and coffee become corridors of inspection where papers are demanded and glances weigh a person’s legality. Cafés dim, shop windows empty, and civic noise thins into the steady clank of trucks and boots.

This spatial reprogramming culminates at Lévitan, an elegant department store repurposed into a prison-factory. Marble floors and display counters survive, but their social meaning flips: the same glass that once invited browsing now reflects the faces of the detained; counters become workstations for sorting stolen heirlooms.

The building itself participates in a black market of memory, forcing Jewish prisoners to handle the intimate artifacts of people who will not be allowed to reclaim them. Even domestic interiors grow suspect. Helaine’s childhood townhouse, a space of care and confinement due to illness, is recoded as a place from which a French officer can trace her father, and later as evidence that her mother has been swept into the deportation machinery.

The garden where Helaine gains purpose transforms into a screen of exclusion when signage bars Jews; the same plot of earth that nurtured vegetables now cultivates complicity. The narrative insists that architecture is not neutral under authoritarian rule. Buildings absorb policy; streets enforce hierarchy; music halls turn into stages for ideological purity tests.

By the time the dormitory wall yields Helaine’s hidden journal, even plaster has become a ledger of captivity, its hash marks counting days the state tried to erase. Last Twilight in Paris makes readers feel how quickly a city can be redesigned to manage, expose, and punish the very people who once animated it.

Secrets, silence, and the afterlife of trauma

The 1953 storyline shows how unsaid histories can calcify into distance. Louise and Joe inhabit a postwar marriage built on withheld stories, the ordinary rituals of parenting carrying an undertow of unshared nights, smells, and faces. Their house, thrown up on a bomb site, looks respectable until one stands close; their relationship mirrors that architecture.

Louise’s restlessness is not simple nostalgia for danger; it is the ache of a narrative stuck behind her teeth. Joe drinks to quiet what he cannot narrate, assigning routines to Louise as if domestic order could replace absent testimony. The Mizpah charm functions like a key that turns tumblers in the psyche. Touching it returns Louise to the camp roads, to Franny’s staged glamor and backstage terror, to the choice she could not make for her friend.

The longer she avoids naming that night and the sex born from shock and guilt, the thicker the membrane between her and Joe becomes. Helaine’s trauma also seeks form: a tally on a wall; a journal walled up behind plaster; a last name revised to hold both past and chosen family. When, in the present, Louise reads Helaine’s handwriting and later hands over developed film, private wounds turn into shared objects that can be held, dated, and discussed.

The novel suggests that healing does not arrive through forgetting but through testimony that restores sequence and cause. Even rage wants a timeline. By prosecuting Ian and returning the necklace, the characters externalize betrayal into artifacts and legal statements; in doing so, they reduce the power of spectral memory to rule their attachments.

Last Twilight in Paris argues that silence is not neutral—it protects violators and isolates survivors—while speech, however belated, can reroute a life.

Women’s agency against social and structural constraint

Helaine’s life begins under layers of containment: a body weakened by influenza, a mother’s anxious love that confines her to a townhouse, a father’s authority that would barter her future for family reputation. Her walk to hear a cellist is a jailbreak measured in city blocks, but that modest liberty expands into partnership, sex, and work—the basic adult claims denied her by illness and parental control.

War adds a new architecture of constraint. Yellow stars, markets restricted by signage, guards who turn corridors into traps—each institution claims jurisdiction over her body. Agency becomes tactical: choosing to work the garden; deciding whom to trust among guards; marking days in a hidden ledger; initiating a bus escape with a tug on a cord and a shouted command.

Louise’s arc is shaped by peacetime constraints that are less visible but still potent. Small-town expectations about contentment, childcare framed as her solitary duty, and a husband whose pain crowds out her own—all of it reduces her to a function.

Her return to London and then Paris reactivates the capable courier and investigator she once was. She chases addresses, reads floor plans by touch, confronts officials who prefer that a woman go home. By the epilogue she has started a detective agency, turning intuition and persistence into a profession rather than a secret pastime. Franny’s path, though cut short, dramatizes another mode of agency: a performer trading access to German audiences for access to POWs, then repurposing photographs into identity papers. Agency here is costly and sometimes fatal, but it is unmistakably present.

Last Twilight in Paris honors choices women make in tight corridors—romantic, logistical, ethical—and shows how those choices accumulate into lives that cannot be dismissed as passive endurance.

Love, loyalty, and the economics of survival

Romance in this story is not a refuge from history; it is a budget ledger constantly balanced against ration cards, permits, and rumors. Helaine and Gabriel’s intimacy opens a world beyond parental surveillance, but that same intimacy becomes the motive for dangerous bargains: he negotiates with orchestras that curry favor with occupiers; she risks punishment to pass spoons of silver to the resistance; each lies to authorities to protect the other.

The half-heart necklace literalizes what the couple must practice: division and reunion. It breaks, travels, hides, surfaces—always a step behind their need for assurance. For Louise and Joe, loyalty is tested across years of omission. Joe asserts care through the language of prohibition—don’t go, don’t stir up the past—while Louise seeks care through pursuit—find the name, open the wall, develop the film.

Their final rapprochement depends not on choosing the same method but on recognizing the motive both share: to keep the other alive in a world that did not keep their friends. Parental love is present in smaller, telling moments: Midge the shopkeeper who permits the necklace to be kept; Isa who smuggles food across a moral no-man’s-land; Annette who slips money onto a hall table even as her husband thunders at the door. Loyalty fails, too. Ian converts trust into currency, buying influence with the enemy and paying for it with Franny’s life. The novel never lets love be abstract.

It shows how affection is measured in errands, forged signatures, and the willingness to look at a person and say a hard truth. In Last Twilight in Paris, love is not blind; it is vigilant, improvising shelter one decision at a time.

Identity, names, and the right to narrate oneself

Illness once defined Helaine in her parents’ eyes; Jewishness defines her in the occupiers’ ledgers; prisoner number defines her at Lévitan. Against these imposed tags, she builds identity through names she chooses and records she authors. Adding Lemarque to Weil in her journal is less a legal formality than a claim to lineage that includes both origin and chosen bond.

After the war, Gabriel taking her surname reverses patriarchal custom and acknowledges that, while his music saved her spirit, her persistence saved his life. The novel treats documents as both weapons and shields. Yellow stars and work rosters seek to fix identity for targeting; forged papers and cropped photographs reshape identity for survival. Franny plays with stage names and roles, but the war drags her into a final role in which her real name, attached to a secret errand, becomes a liability.

Louise’s identity is similarly contested. In Henley she is a mother who avoids the school gate’s small talk; in London she is a veteran volunteer and investigator; in Paris she is a petitioner until she becomes a finder. Each setting attempts to lock her into a narrow label; each clue she follows enlarges the frame.

The novel’s artifacts—necklace, journal, negatives—enable characters to narrate themselves to others, often for the first time. Testimony in the present reclaims what was stolen in the past: the right to say who one is and what one endured. Last Twilight in Paris argues that identity is not what the archive says about you; it is the story you can finally tell, backed by fragments you preserved when the state tried to delete you.

Objects as evidence, memory, and leverage

A thin chain, a sliver of metal, a strip of film, a leather notebook—these are the engines that move the plot and the reservoirs that store loss. The Mizpah heart begins as a keepsake, an intimate promise that two lives separated will watch for each other. War refashions it into a courier.

Its inscription becomes a cipher that points to a rendezvous the couple may never keep; its cavity hides film that can unmask a traitor. Because the necklace passes through so many hands—Franny’s purse, a violinist’s pocket, a thrift crate etched with an old store’s name—it accumulates stories the way metal gathers fingerprints. When Ian steals it, we feel how power seeks to confiscate the very objects that could destroy it. The film’s development is a quiet revolution.

A background figure captured on an ordinary frame—an officer receiving an envelope from a civilian—transforms suspicion into chargeable fact. The journal’s recovery repeats that gesture in the register of feeling: Helaine’s sentences return, intact, from the wall that tried to erase her. Objects here are not passive mementos; they are legal exhibits, maps, confessionals, and bridges. They enable the living to face each other without drowning in the scale of what happened. Their smallness matters.

In a narrative crowded with trucks, barracks, and ministries, the decisive instruments fit in a hand or a pocket. Last Twilight in Paris elevates such things without romanticizing them, showing how, under regimes that falsify records and seize archives, personal artifacts can outlast bureaucratic lies and refit memory for justice.

Art, performance, and the double life of beauty

Music and theater offer joy, refuge, and cover. Gabriel’s cello piece for Helaine embodies a private language of attention—phrases shaped to her breath, motifs he wants her to carry when he is gone. That same talent becomes his passport to travel under supervision, to overhear officers, and to seek bribes’ routes.

Beauty is both invitation and alibi. Franny’s concerts inside camps model that paradox even more starkly. On stage, she delivers glamour to men reduced to numbers, restoring for an hour the feeling that they are citizens of a world where applause matters. Offstage, she uses the machinery of performance—cameras, posed photos, autograph lines—to create raw material for escapes.

Art is not a luxury here; it is a toolkit. Yet the book also records art’s vulnerability to commandeering. Repertoires are censored; audiences are policed; halls become sorting mechanisms for race laws. Gabriel’s refusal to play certain composers is read by authorities as disobedience, by colleagues as recklessness, by his wife as a risk they may not survive.

The question becomes whether beauty can remain honest when the stage is owned by a regime that lies. Last Twilight in Paris answers by showing art that carries truth in its methods, not just its messages: a melody that smuggles hope into a barrack; a snapshot that smuggles identity into a file; a performance that smuggles witness into a camp ledger. The cost is steep—Franny’s life, Gabriel’s imprisonment—but the work endures, as a tune heard again years later and recognized immediately as the shape of a promise kept.

Betrayal, complicity, and reckoning

The exposure of Ian’s treason reframes earlier scenes with a jolt. His cautious rhetoric about preserving access to POW camps suddenly reads as self-protection and asset management.

The Red Cross badge that once signified moral authority becomes a cloak for espionage aimed at shoring up German advantage and feeding Britain misinformation. This betrayal operates on multiple layers: professional (corrupting a humanitarian channel), personal (weaponizing Louise’s trust and Franny’s plea), and civic (a citizen sabotaging his own country’s war effort).

The narrative also tracks everyday complicity. French officers who herd women into trucks; shop managers who insist a former department store has no connection to the past; guards who flirt and threaten in the same breath—all furnish the occupation with an infrastructure of ordinary obedience. Reckoning arrives through evidence and relationship. The film gives courts what they require; Helaine’s and Louise’s testimony gives communities what they require to believe. Importantly, reckoning does not promise repair. Franny remains dead; Miriam’s fate is sealed on a bus; countless objects never find their owners.

What justice can offer is clarity and the chance to live without accommodating a lie. When Gabriel explains why he took Helaine’s surname, when Joe agrees to therapy, when Louise opens an agency to look for the missing, these choices enact an ethic opposite to Ian’s: to use one’s roles—artist, spouse, investigator—as instruments of truth rather than camouflage. Last Twilight in Paris ends not with vengeance but with accountability, which is smaller and steadier, and with the commitment to keep looking for those who never came home.