Fundamentally by Nussaibah Younis Summary, Characters and Themes

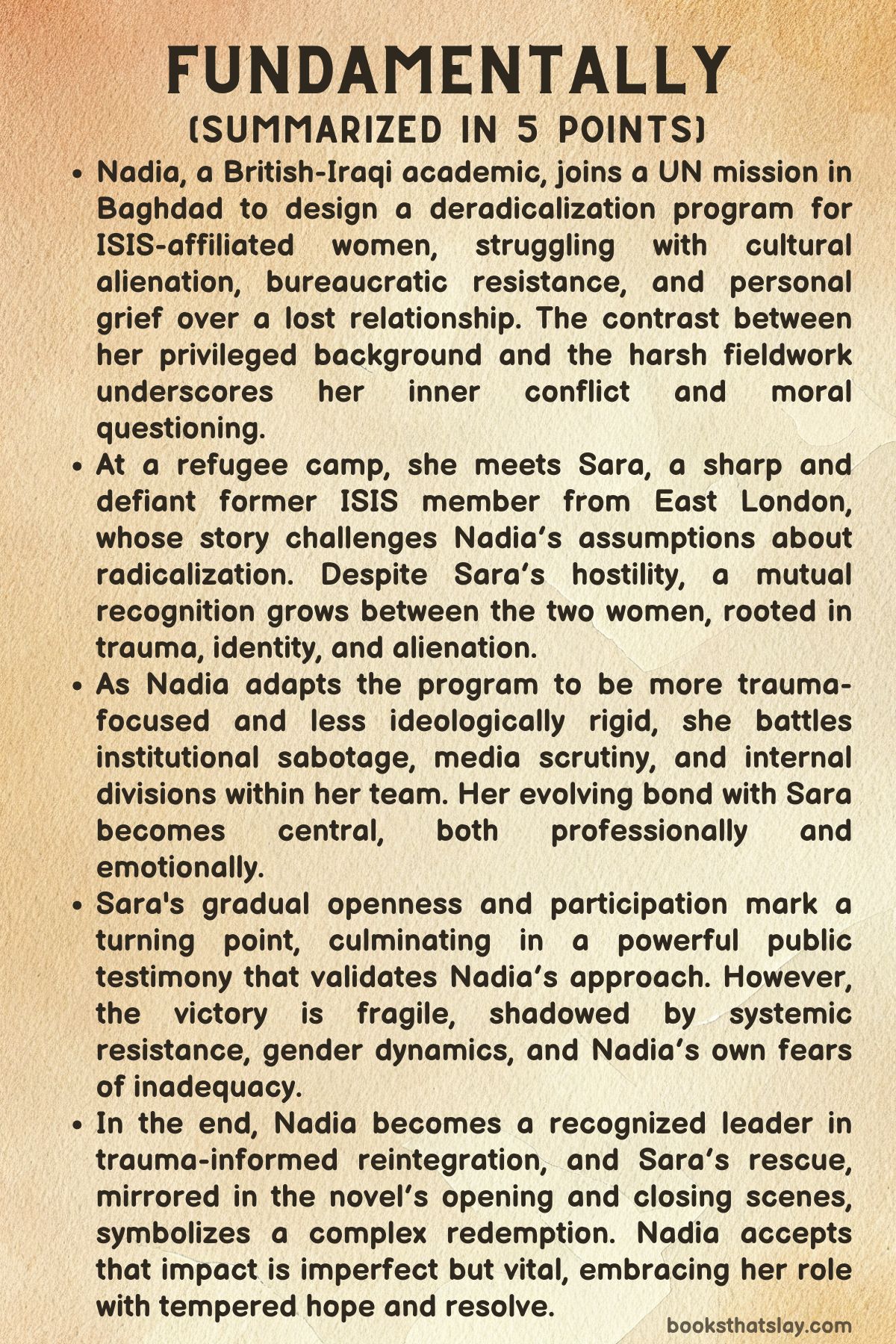

Fundamentally by Nussaibah Younis is a thought-provoking narrative centered around Dr. Nadia Amin, a dedicated UN aid worker who is stationed in Iraq to lead a program aimed at deradicalizing women who were once affiliated with ISIS.

The novel explores themes of personal identity, moral duty, and the complexities of international aid in a conflict-ridden environment. As Nadia tries to reconcile her professional role with her own personal struggles and emotional turmoil, she must navigate the challenges of a morally ambiguous mission while dealing with the consequences of her own fractured past. The story unfolds with sharp insights into human rights, international politics, and the deeply personal toll of trying to enact change in a broken system.

Summary

Dr. Nadia Amin, a criminologist by training, finds herself working in Iraq for the United Nations on a delicate and morally complicated mission: to rehabilitate ISIS brides.

The novel begins with Nadia’s arrival in Iraq, where she faces the harsh realities of a volatile environment and the emotional weight of her assignment. Nadia’s personal life, marked by a painful breakup with her close companion Rosy and her strained relationship with her religious mother, haunts her throughout her journey, as she tries to escape from her past while working in a completely unfamiliar and dangerous context.

The program Nadia leads aims to deradicalize women who had been involved with ISIS, but her lack of practical experience in this area quickly becomes evident. Her intellectual knowledge of criminology and radicalization does little to prepare her for the complexities of dealing with the women in the camp, who are not merely perpetrators but victims of a broader political and social catastrophe.

Nadia’s feelings of isolation deepen as she struggles to connect with her colleagues. While some, like Tom, a muscular security officer, offer her a semblance of support, their professional relationship does little to alleviate the profound loneliness and anxiety she experiences.

As Nadia embarks on her mission, she finds herself in a difficult and precarious position. She is thrust into leading a team of specialists tasked with rehabilitating the women who were once affiliated with ISIS.

The work is both exhausting and emotionally draining, and Nadia feels overwhelmed by the moral and ethical weight of her responsibilities. Her initial optimism soon gives way to doubt as she faces the difficulties of communicating with women who have been traumatized, manipulated, and shaped by radical ideologies.

The first focus group she leads with former ISIS brides challenges her preconceptions and forces her to see the humanity in the women she is meant to help. The realization that these women are both victims and perpetrators, shaped by a horrific set of circumstances, forces Nadia to reassess her beliefs and approach to rehabilitation.

One of the key women Nadia interacts with is Sara, a young British woman who had been involved with ISIS. Nadia becomes emotionally invested in Sara’s story, seeing in her a reflection of her own past struggles with identity and belonging.

As Nadia works with Sara, she realizes the depth of the trauma these women have experienced and the difficulty of reintegrating them into society. Sara’s journey is one of resistance, as she grapples with her loyalty to ISIS and the difficulties of letting go of a past that has defined her.

Nadia’s attempts to help her are often met with rejection, and she is forced to confront the limits of her role in Sara’s life. The tension between Nadia’s desire to help and the realization that she may never fully be able to save Sara becomes a central conflict of the narrative.

Nadia’s personal struggles are not confined to her work with the women in the camp. Throughout the story, she grapples with her own sense of identity and her complicated relationship with her family.

Her mother’s disapproval of her work in Iraq and their strained relationship add an emotional layer to her already challenging life. Nadia’s attempt to distance herself from her family and her past is complicated by the guilt she feels about her mother’s feelings and the pressure of constantly trying to prove herself in a professional capacity that she never truly wanted.

This ongoing emotional conflict parallels her work with the ISIS brides, as she attempts to repair the lives of others while grappling with her own unresolved emotional issues.

As the story progresses, Nadia’s professional and personal lives become increasingly intertwined. The bureaucracy of the UN and the political hurdles she faces in Iraq make her mission even more difficult.

Nadia is often thwarted by the systemic obstacles that seem designed to prevent real change. Her interactions with her colleagues further highlight the moral ambiguities of her work.

Figures like Pierre, a cynical colleague, and Sherri, another aid worker, embody the self-serving nature of much of the international aid system. Their indifference to the well-being of the women in the camp, in contrast to Nadia’s genuine efforts to help, forces her to confront the limitations of her role within this larger system.

The climax of the novel comes when Nadia attempts to secure the Iraqi government’s permission to launch the rehabilitation program, only to find herself up against a wall of bureaucracy, corruption, and incompetence. The internal politics of the UN, which prioritize self-interest over real change, come into sharp focus during a series of frustrating meetings.

Despite these setbacks, Nadia remains determined to push forward with the program, hoping that it will lead to some positive change for the women in the camp.

In the final stages of the novel, Nadia reaches a turning point. She is confronted with the realities of her work and the profound challenges of trying to rehabilitate individuals caught in the web of international conflict.

As she faces the growing frustration of working in a broken system, Nadia begins to question her own motivations and the true feasibility of the rehabilitation program. Despite her doubts, she manages to secure an agreement from the relevant UN agencies, allowing her to continue her mission.

This moment of success, however, is tempered by her realization that the road ahead will be long, difficult, and fraught with moral and personal challenges.

The novel concludes with a nuanced examination of the nature of international aid and the personal toll of working in a conflict zone. Nadia’s journey is one of personal growth and self-discovery, but it is also a sobering critique of the international aid system and the ethical dilemmas faced by those who attempt to enact change in a world rife with corruption, political intrigue, and systemic failure.

Ultimately, Nadia’s experiences in Iraq serve as a lens through which the novel explores the complexities of human nature, identity, and the moral ambiguities of trying to make a difference in a world filled with pain and suffering.

Characters

Dr. Nadia Amin

Dr. Nadia Amin is a complex and emotionally nuanced character, at the heart of Fundamentally.

As a UN worker in Iraq tasked with leading a program for the rehabilitation of ISIS brides, Nadia grapples with a range of personal and professional challenges that profoundly shape her journey. At the start, Nadia is portrayed as a woman deeply troubled by her sense of isolation and a troubled past.

Her emotional distress stems from the breakup with her former partner, Rosy, and her strained relationship with her religious mother, which leaves her feeling disconnected from her roots. Nadia’s role in Iraq, while intellectually appealing due to her background in criminology, forces her to confront the stark realities of a world she feels ill-prepared for.

Throughout the story, Nadia’s internal struggles are evident—her guilt over the past, her self-doubt, and the anxiety that bubbles to the surface as she navigates the emotional and professional difficulties of her job. Her personal growth, however, is driven by her experiences with the women in the rehabilitation program, especially Sara, whose life mirrors Nadia’s own struggles with identity, rejection, and the complex politics surrounding global conflict.

Nadia’s journey is one of self-discovery, where she learns to confront the limitations of her position and the moral ambiguities of her work, ultimately realizing that her role is to guide, not to save, those like Sara. This realization marks a pivotal moment in her character arc, as she learns to let go of the idea of absolute control over others’ lives, while continuing to contend with her own unresolved emotional baggage.

Sara

Sara is one of the most pivotal characters in Fundamentally, embodying the complexities of loyalty, trauma, and identity. A former ISIS bride, Sara is caught between her past affiliations and the present reality she must navigate, which leads to profound inner conflict throughout the story.

Initially, Sara’s resistance to Nadia’s attempts at reintegration into a more ordinary life in Gaziantep highlights her attachment to her Muslim identity and her past beliefs. Sara is not simply a victim of manipulation; she is a deeply conflicted individual struggling with the consequences of her choices.

Her resistance to Western values and the pull of her past allegiances to ISIS make her a difficult, yet sympathetic, character. The emotional conflict that arises between her and Nadia is profound, as Sara’s choices serve as a painful reminder of Nadia’s own struggles with identity and familial rejection.

Throughout the narrative, Sara’s psychological and emotional complexity deepens, particularly when she chooses to reconnect with her past, leading to feelings of betrayal for Nadia. However, this choice also symbolizes Sara’s agency in reclaiming her own path, even if it diverges from the life Nadia envisions for her.

The resolution of Sara’s arc, where she reconciles with her parents, offers a bittersweet closure for Nadia, as she comes to understand that her role was never to save Sara but to facilitate her journey towards self-reconciliation.

Pierre

Pierre serves as a foil to Nadia, embodying the cynicism and selfishness that pervades much of the bureaucratic structure within the UN. A colleague whose political maneuvering often undercuts the efforts of those like Nadia who are trying to make a real difference, Pierre exemplifies the frustrations that many humanitarian workers face in dealing with a system more concerned with career advancement and self-interest than actual change.

Though Pierre helps Nadia navigate the political intricacies of the UN’s internal politics, his selfishness forces Nadia to confront the ethical dilemmas of her work. His presence in the narrative highlights the systemic challenges faced by aid workers, and his character arc serves as a critique of the corporate-like structures that often define humanitarian aid efforts.

As Nadia struggles with the inefficiencies of the system, Pierre’s manipulative tendencies act as a painful reminder of the compromises required to navigate the political landscape in Iraq, thus contributing to Nadia’s growing disillusionment with the system around her.

Sherri

Sherri, like Pierre, plays a role in highlighting the morally ambiguous world of international aid work. While Sherri provides some practical support to Nadia, she too is driven by her own personal motives.

Her interactions with Nadia reveal the self-serving nature of the humanitarian system and the difficulty of relying on colleagues who may not share the same commitment to the mission. Sherri’s actions demonstrate the compromises that workers within such systems often make, which ultimately affects Nadia’s ability to make meaningful progress in her mission.

While Sherri is not as overtly manipulative as Pierre, her indifference to the deeper, emotional needs of the women she’s supposed to be helping makes her character a subtle yet significant force in the narrative, forcing Nadia to question whether the goals of the rehabilitation program can ever be truly achieved.

Tom

Tom, the muscular security officer, provides a source of support for Nadia, though in a somewhat limited capacity. His attempts at light-hearted banter offer brief moments of relief from the heavy emotional and professional burdens Nadia faces, but they ultimately fail to ease her deeper anxieties.

Tom’s character represents the often-overlooked figures in high-stakes environments, those whose roles are not directly tied to the central mission but who provide some form of emotional buffer for the main characters. Despite his well-meaning nature, Tom’s presence underscores Nadia’s isolation—her dependence on external support, which, while comforting, cannot alleviate the more profound struggles she faces internally.

Through Tom’s interactions with Nadia, the story reflects on the nature of external relationships in conflict zones, where even well-meaning individuals can only offer so much in terms of real, meaningful connection.

Themes

Moral Ambiguity and Professional Duty

In Fundamentally, the theme of moral ambiguity is central to Nadia’s character and her work. As a UN aid worker tasked with leading a rehabilitation program for ISIS brides, Nadia is caught in a complex web of personal and professional dilemmas.

The moral complexities arise not only from the women she is trying to help but also from the bureaucratic system she is a part of. Her job requires her to help people who were involved in atrocities, yet many of these women are also victims of manipulation, coercion, and violence.

Nadia’s struggle to balance her desire to aid these women with her growing awareness of the system’s limitations highlights the tensions between idealism and reality. In this morally gray environment, she finds herself questioning the effectiveness of her work, the motivations of those around her, and even her own ability to make a tangible difference.

This internal conflict deepens as Nadia interacts with colleagues like Pierre and Sherri, who, while seemingly supportive, are driven by their own personal agendas. Ultimately, Nadia’s journey reveals the challenges of maintaining personal ethics and compassion within a flawed, often corrupt international aid system.

Identity and Belonging

Nadia’s internal journey is marked by a profound sense of isolation and alienation, both in her personal life and in her work environment. As a woman of immigrant descent, Nadia struggles to reconcile her identity with her professional role in Iraq.

Her emotional dislocation is amplified by her past trauma, particularly her estranged relationship with her religious mother and her unresolved grief over her breakup with Rosy. These unresolved issues complicate her sense of belonging in Iraq, where she is physically removed from everything familiar, and within the international community, where she feels like an outsider.

The narrative explores the tension between Nadia’s desire to fit in and her recognition that she may never fully do so. This theme of identity is not just limited to Nadia, but extends to the women she is tasked with rehabilitating, especially Sara, who also grapples with her own sense of self amidst the trauma of being an ISIS bride.

The personal and professional struggles in the narrative underscore the complexities of finding one’s place in the world when surrounded by societal expectations, political pressures, and personal trauma.

Trauma and the Weight of the Past

The theme of trauma is pervasive in Fundamentally, affecting both Nadia and the women she seeks to help. Nadia’s personal trauma—stemming from her failed relationships and her strained family ties—often resurfaces throughout her work in Iraq, influencing her decisions and her emotional state.

This personal grief parallels the trauma experienced by the women in the rehabilitation program, particularly Sara, whose past with ISIS continues to haunt her in profound ways. The narrative highlights the difficulty of moving past trauma, both for individuals and for communities, and explores how the weight of the past can shape one’s present and future.

For Nadia, her own unresolved pain complicates her attempts to help others, as she often projects her own emotional needs onto the women in the camp. For Sara, the process of healing is complicated by her loyalty to her past and her ideological beliefs, making her journey toward recovery even more difficult.

Through these intertwined stories, the narrative explores the long-lasting effects of trauma and the emotional toll of trying to move forward while being constantly pulled back by the past.

Bureaucracy and Systemic Inefficiency

Throughout Fundamentally, the theme of bureaucracy and systemic inefficiency is explored in detail, emphasizing how these issues hinder the effectiveness of humanitarian efforts. Nadia’s struggle to launch the rehabilitation program is often thwarted by political and bureaucratic roadblocks, with local officials and international organizations more focused on maintaining their own power and careers than on helping the women in the camp.

The story critiques the often hollow nature of international aid efforts, where well-intentioned policies are diluted by corruption, incompetence, and a lack of genuine concern for the people they aim to help. Nadia’s frustration with the slow-moving and ineffective system serves as a critique of the broader international community’s approach to global issues.

Her efforts to bring about meaningful change are frequently stymied by red tape and self-interest, making her question the feasibility of her mission and her own role in it. The portrayal of bureaucracy in the narrative highlights the disconnect between the ideals of international aid and the realities of its implementation, raising important questions about the true effectiveness of global humanitarian efforts.

Cultural Clashes and the Limits of Western Ideals

A significant theme in Fundamentally is the clash between Western values and the cultural beliefs of the women Nadia is trying to help. As Nadia works with Sara, she finds herself grappling with the tension between her desire to help Sara adapt to a more “normal” life and Sara’s resistance to Western values, particularly the notions of freedom, autonomy, and individualism that Nadia embodies.

Sara’s attachment to her past and her loyalty to her Muslim identity, shaped by her experiences in Mosul, creates a barrier between the two women. Nadia’s attempts to guide Sara into a new life are met with resistance, forcing Nadia to confront the limits of her understanding and the cultural assumptions that inform her approach.

This clash of values raises complex questions about the effectiveness of Western intervention in foreign conflicts and the challenge of imposing foreign ideals on people who may not share the same cultural context. The theme of cultural clash also extends to Nadia’s own struggle with her identity, as she tries to reconcile her Western upbringing with her role in the Middle East, where her values and approach are often at odds with the local reality.

Guilt and Responsibility

The theme of guilt and responsibility is central to Nadia’s emotional journey in Fundamentally. Nadia constantly grapples with a sense of guilt, both personal and professional.

She feels responsible for her failure to help Sara as she had hoped and is burdened by the belief that she could have done more to ease Sara’s suffering. This guilt is compounded by her personal history of estrangement from her family and her unresolved feelings about her breakup with Rosy.

Professionally, Nadia feels responsible for the success or failure of the rehabilitation program, and her growing realization that systemic corruption and political self-interest may render her efforts meaningless adds to her sense of helplessness and frustration. Nadia’s journey is marked by a constant tension between her desire to help and her awareness of the limitations of her ability to effect change.

This sense of responsibility is further complicated by her growing understanding that, despite her best efforts, she may not be able to save Sara or make a lasting difference in the lives of the women in the camp. Ultimately, the theme of guilt highlights the emotional toll of working in such a complex and morally ambiguous environment.