One Day Everyone Will Have Always Been Summary, Analysis and Themes

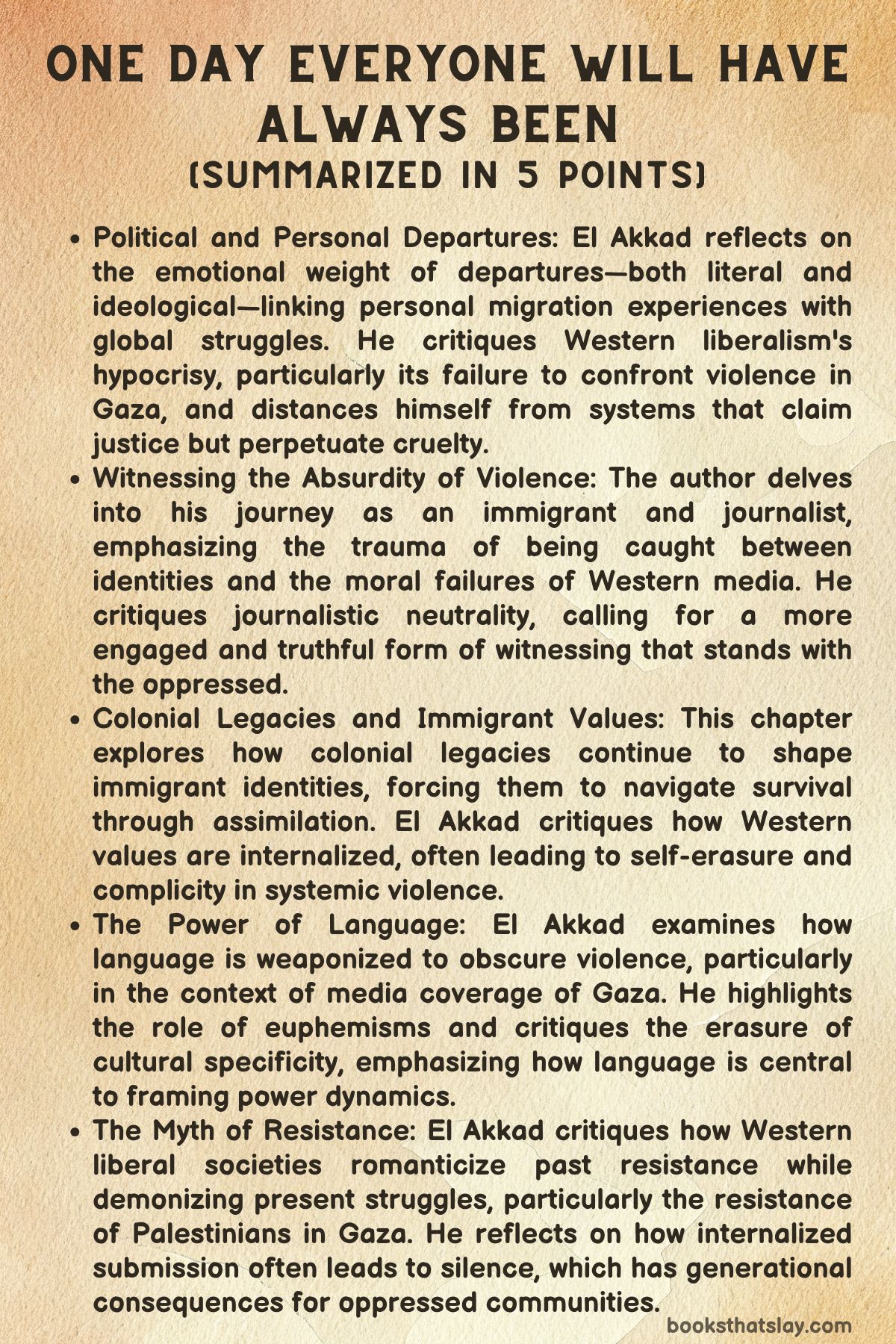

One Day Everyone Will Have Always Been by Omar El Akkad is a searing, deeply personal meditation by Omar El Akkad on war, exile, complicity, and moral clarity in a collapsing world.

Blending memoir, political essay, and cultural critique, the book interrogates Western liberalism’s hollow moral posturing in the face of atrocities like the Gaza genocide. Through reflections on migration, identity, language, journalism, and parenthood, El Akkad maps the internal landscapes of grief and disillusionment. His writing is urgent, mournful, and unflinchingly honest—an effort to name what must be named, to resist erasure, and to confront the violence of systems that claim virtue while perpetuating harm.

Summary

One Day Everyone Will Have Always Been follows the narrative of a father who grapples with the complexities of raising his children in the United States while being disconnected from his homeland in the Middle East. Through reflections on his own childhood, the narrator reveals his inner struggle with the dissonance between his children’s Western upbringing and his own Middle Eastern roots.

The story begins with a reflection on his daughter’s imaginative world, which starkly contrasts with his own childhood, marked by displacement and alienation. As a parent, the narrator faces the decision of whether to reconnect his children with their heritage, but his fear of the prejudices and difficulties they might face prevents him from doing so.

This reluctance stems from the legacy of exile in his family, particularly his father’s flight from Egypt due to political instability.

The themes of exile and the cost of belonging dominate the early chapters, as the narrator reflects on his father’s experiences in Egypt and Qatar. His father’s escape from Egypt and subsequent life as a refugee illustrate the larger challenges faced by those who leave their homelands in search of safety and opportunity.

The narrator’s own experiences mirror his father’s, but he struggles to reconcile these with his identity as a father raising children who are distanced from the cultural and political realities that shaped his own upbringing. His sense of alienation is heightened by the violence and suffering he sees in the world, particularly in Gaza, and his disillusionment with the Western powers who perpetuate these global injustices.

As the story progresses, the narrator’s personal reflections expand to include a critique of Western foreign policy and the moral decay of Western liberalism. He describes his feelings of disillusionment regarding the West’s passive complicity in global conflicts and violence, especially in the context of the ongoing violence against Palestinians.

Through his lens, the West’s endorsement of such actions reflects the hypocrisies and failings of past imperial powers, highlighting the contradiction between Western values of freedom and the reality of violence and oppression in the Middle East.

The narrative then shifts to a specific childhood memory, where the narrator recalls an incident in Qatar that left a lasting impact on him. He witnessed a violent confrontation between a local man and a migrant worker, an event that exposed the deep racial and class divisions in the Gulf.

This memory becomes a metaphor for the broader systemic violence that characterizes the relationships between different groups in the region, particularly the dehumanization of migrant workers. The narrator’s discomfort with this violent act also reflects his larger critique of the power structures that perpetuate such inequalities.

The personal and the political continue to intersect as the narrator reflects on the disconnect between the privileged Western perspective and the lived reality of those in the Middle East. Raised in a world shaped by colonial powers and Western norms, the narrator contemplates the irony of his own family’s assimilation into Western society.

Despite their outward integration, they remain marked by the history of displacement, and this tension between assimilation and cultural preservation becomes a central theme in the story. The narrator’s internal struggle is a reflection of the larger issues faced by many immigrants who are forced to choose between maintaining their cultural identity and adapting to a society that often marginalizes them.

In the following chapters, the author delves deeper into the emotional complexities of loss and grief, particularly in the wake of the narrator’s father’s death. The funeral rituals and burial in Egypt evoke feelings of familial connection that have been eroded over time due to migration.

The pain of this loss is amplified by the realization that the narrator’s ties to his family and his heritage have become distant and unfamiliar. This chapter also highlights the emotional toll of political unrest in the Middle East, as the narrator finds himself caught between personal loss and his journalistic duties to report on the region’s ongoing conflicts.

The narrative further explores the role of the writer in confronting political violence, drawing a stark contrast between the silence of the literary community and the brutality of war and oppression. The narrator reflects on his experience as a journalist covering the political turmoil in Egypt following President Mohamed Morsi’s controversial decrees, which led to mass protests.

His disillusionment with the political system deepens as he observes the hypocrisy of Western leaders who claim to support democracy while backing oppressive regimes. This critique of political systems is paired with an exploration of the writer’s responsibility to engage with the world’s injustices.

The narrator grapples with the ethical dilemma of whether writing can ever truly resist or challenge the power structures that perpetuate violence.

In this section, the author raises important questions about the role of art and literature in political resistance. He reflects on the passivity of writers who fail to speak out against systemic violence, noting that silence in the face of atrocities is a form of complicity.

The narrator’s refusal to participate in industries that profit from exploitation and his decision to avoid lavish ceremonies highlight his internal struggle to align his actions with his moral beliefs. This section underscores the tension between comfort and resistance, suggesting that even small acts of disengagement can be a form of defiance against the larger systems of power.

The final chapters return to the theme of resistance, emphasizing the importance of both active and negative resistance in challenging the systems of oppression that sustain violence and injustice. The narrator concludes by reflecting on the possibility for change, however small or incremental, and the power of human solidarity in the face of overwhelming adversity.

Through personal acts of resistance, whether through boycotts, protests, or simply refusing to participate in the status quo, individuals can challenge the structures of power that perpetuate human suffering. The author argues that despite the scale of the injustice, it is crucial to maintain moral clarity and solidarity in times of crisis.

The book ends with a call to action, urging readers to confront the systemic injustices that define modern life. The text is a meditation on how individuals, through their choices and actions, can either contribute to or resist the ongoing cycles of violence and oppression.

Ultimately, One Day Everyone Will Have Always Been is a profound reflection on the intersection of personal identity, political engagement, and the ethical challenges of living in a world marked by inequality and suffering.

Key Persons in the Narrative

The Narrator (Omar El Akkad)

The narrator in One Day Everyone Will Have Always Been is a complex character caught between multiple identities, shaped by the crosscurrents of migration, political upheaval, and personal loss. As a father raising his children far from his homeland, he is deeply reflective about the generational divide and the cultural dissonance between his upbringing in the Middle East and his children’s experiences in the United States.

His relationship with his own background is fraught with tension, as he grapples with the painful memories of marginalization due to his Arabic name and accent. This sense of alienation is further compounded by his father’s escape from Egypt, an event that marks the narrator’s understanding of survival in the face of political oppression and exile.

The narrator’s emotional struggle with his heritage is reflected in his reluctance to reconnect his children with their Arab roots, driven by his own fears and memories of racial and cultural discrimination. His disillusionment with the West, particularly in its passive complicity with global injustices, adds another layer to his character, highlighting his frustration with the hypocrisy of Western liberalism and its approach to conflicts like those in Gaza.

His internal conflict between personal identity, survival, and moral integrity underscores the complex nature of belonging in a globalized world.

The Father

The father of the narrator plays a significant yet largely background role in One Day Everyone Will Have Always Been. His experience as an exile fleeing Egypt due to political instability shapes much of the narrator’s perspective on survival and displacement.

The father’s escape symbolizes the painful sacrifices made for the sake of safety and opportunity, but it also reveals the emotional cost of leaving behind one’s homeland and the legacy of trauma that is passed on to the next generation. His story is one of resilience and the search for a better life, themes that are central to the narrator’s own journey.

Despite his physical absence in much of the narrative, the father’s impact resonates deeply within the narrator’s reflections on his own role as a parent and the legacy of migration. The father’s experience of exile, as well as the generational trauma it brings, is a critical aspect of the narrator’s exploration of identity, belonging, and the complexities of being an outsider in both the Middle East and the West.

The Narrator’s Daughter

The narrator’s daughter represents a juxtaposition of innocence and imagination in One Day Everyone Will Have Always Been. Her creation of paper cities and fantasy worlds symbolizes her attempt to escape the realities of displacement and find a space for her own identity amidst the complexities of her father’s fractured relationship with his heritage.

Her innocence contrasts sharply with the narrator’s own sense of alienation and loss, creating a generational divide that underscores the complexities of growing up between two cultures. She embodies a sense of hope and creative potential, yet her very existence within this constructed world highlights the tension between her father’s desire to protect her from the harsh realities of the world and her own desire for exploration and self-expression.

Through her character, the narrative touches on the fluid nature of identity and the ways in which younger generations are forced to navigate the legacies of their forebears while crafting their own sense of belonging.

The Migrant Worker

The migrant worker featured in the narrator’s childhood memory in One Day Everyone Will Have Always Been serves as a poignant symbol of the dehumanization and exploitation that defines much of the global political landscape. The violent act witnessed between the local man and the migrant worker in Doha, Qatar, is a stark reminder of the racial and class divisions that permeate the Gulf region.

The migrant worker is rendered invisible, his suffering ignored by those in positions of power and privilege, much like the larger systemic violence that exists in various forms across the globe. This incident, which the narrator reflects on with deep unease, becomes a microcosm of the broader issues of exploitation and marginalization that shape the experiences of those displaced by war, poverty, and political instability.

Through this character, the narrative critiques the global power structures that allow such violence to persist, while also exploring the psychological impact of witnessing such inhumanity.

The Journalist

The journalist character in One Day Everyone Will Have Always Been plays an essential role in reflecting the intersection of personal loss and professional duty, particularly as the author grapples with grief and the broader political situation in the Middle East. His role as a journalist covering political unrest in Cairo underscores the tensions between personal identity and professional obligation, especially when reporting on the violence and injustice that defines much of the region’s contemporary history.

His reflections on the hypocrisy of Western powers, particularly in their support of oppressive regimes, mirror the broader themes of disillusionment with political systems and their failure to address the true sources of violence and suffering. Through the journalist’s perspective, the narrative critiques the role of media and the ways in which the story of conflict is often shaped by the interests of those in power.

His struggle with moral engagement versus disengagement also serves as a meditation on the ethics of reporting in an age where silence and complicity are often seen as easier paths than resistance.

The Writer

The writer character in One Day Everyone Will Have Always Been is deeply introspective, questioning the role of art and literature in confronting systemic violence. As someone who reflects on the moral obligations of writers in times of crisis, this character contemplates whether it is possible to create meaningful art in a world increasingly indifferent to human suffering.

The writer’s personal reflections on the Giller Prize protest and the silence of many literary figures in the face of ongoing atrocities illustrate the tension between artistic creation and political activism. This character’s internal struggle revolves around the intersection of personal expression and collective responsibility, raising important questions about the capacity of art to stand as a form of resistance in the face of ongoing global violence.

Through this character, the narrative explores the ethical quandaries of engaging with a world where passive complicity is often the norm, challenging the notion that art can remain detached from the brutal realities of geopolitics.

Themes

Displacement and Identity

The theme of displacement and its effect on identity is central to One Day Everyone Will Have Always Been. The narrator’s reflections on raising his children in the United States, far from his homeland, highlight the dissonance between his children’s upbringing and his own experiences growing up in the Middle East.

He struggles with the challenge of preserving his cultural heritage while protecting his children from the prejudice and alienation he himself faced due to his Arabic name and accent. This tension is rooted in the narrator’s complex relationship with his background, as he distances his children from their Arab roots, hoping to shield them from the painful realities of being an outsider.

This sense of identity is further complicated by his own memories of his father’s escape from Egypt due to political instability, which adds layers to his understanding of exile and the pursuit of safety in foreign lands. The theme explores not only the personal consequences of uprooting but also the broader political ramifications of migration and forced exile, where individuals are often compelled to abandon parts of their identity for survival.

Colonialism and the Power Structures of the West

Through the narrator’s journey, One Day Everyone Will Have Always Been critiques colonialism and the power structures that have shaped the modern world. The narrator’s disillusionment with Western liberalism and the complicity of Western powers in global conflicts, such as the violence in Gaza, reveals a deep skepticism of the West’s moral posturing.

The narrative examines the paradox of being raised in a world influenced by Western norms and language, while simultaneously recognizing the injustices and hypocrisies inherent in these systems. The narrator’s reflections on his father’s escape from Egypt to Qatar, and the racial and class divisions he witnessed there, underscore the dehumanizing impact of colonial legacies that persist in contemporary global politics.

The theme critiques the West’s historical and ongoing interference in the Middle East, highlighting the ethical dilemmas of participating in a global system that often serves to perpetuate inequality, violence, and exploitation.

The Moral Failures of Global Power

The theme of the moral decay of global power is explored through the narrator’s disillusionment with the actions of Western nations, particularly in relation to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The narrator’s reflections on the passive complicity of Western powers in global injustices, such as the endorsement of violence against Palestinians, serve as a critique of the double standards that exist in global politics.

The narrative questions the sincerity of Western ideals, especially in light of the systemic violence that continues unchecked in the Middle East. The author uses his own experiences and observations to illustrate the fragility of moral integrity within geopolitics, showing how powerful nations often prioritize political convenience and economic gain over human rights and justice.

This theme is poignant in its exploration of how political and economic systems become entrenched in cycles of violence, making it difficult for individuals and nations to break free from these moral compromises.

Systemic Violence and Human Suffering

The theme of systemic violence is introduced through the narrator’s memory of witnessing a violent act between a local man and a migrant worker in Doha, Qatar. This moment serves as a metaphor for the larger systemic violence that pervades the world, particularly in the context of migrant labor.

The narrative critiques the dehumanization of migrant workers, who are often invisible and subject to extreme exploitation in regions like the Gulf. The violence is not just physical but deeply ingrained in the social and political structures that marginalize these workers.

This theme is expanded to encompass the broader patterns of violence and exploitation that exist globally, particularly in relation to the ongoing suffering of Palestinians in Gaza. The author’s reflections on the indifference of global powers to the suffering of marginalized people underscore the pervasiveness of systemic violence, which is sustained by the complicity of those in power.

The Role of Writers and the Ethics of Engagement

In the chapter reflecting on the author’s journalistic and literary experiences, the theme of the role of writers in confronting systemic violence and injustice is explored. The author grapples with the question of whether literature and art can serve as tools of resistance in the face of ongoing violence and oppression.

The narrative critiques the passivity of many writers who remain silent or disengaged from the political crises unfolding around them, noting that silence itself can be a form of complicity. This theme underscores the moral responsibility of writers and artists to use their platforms to challenge injustice, even if it means risking personal or professional sacrifice.

The author’s own refusal to participate in industries that profit from exploitation, as well as his decision to critique Western powers, highlights the ethical dilemmas that individuals face when choosing between moral action and comfort. The narrative presents a call to action for writers and artists to engage actively in the political realities of their time, using their work to bear witness to suffering and to advocate for change.

Resistance and Solidarity

At its core, One Day Everyone Will Have Always Been is a meditation on the possibility of resistance, even in the face of overwhelming power. The author emphasizes that small acts of resistance, such as boycotting or protesting, can create meaningful change, even when the forces of violence and oppression seem insurmountable.

This theme is particularly evident in the chapter’s conclusion, where the author reflects on the power of human solidarity and the importance of maintaining moral clarity in times of crisis. The narrative critiques the broader systems of power that perpetuate violence, yet it also offers hope that individual actions—however small—can contribute to challenging and ultimately dismantling these systems.

The author’s reflections on the potential for change highlight the need for continued resistance and solidarity, even when faced with seemingly insurmountable obstacles. Through this theme, the narrative advocates for collective action and the importance of upholding human dignity in the face of systemic violence.