Swordheart Summary, Characters and Themes | T. Kingfisher

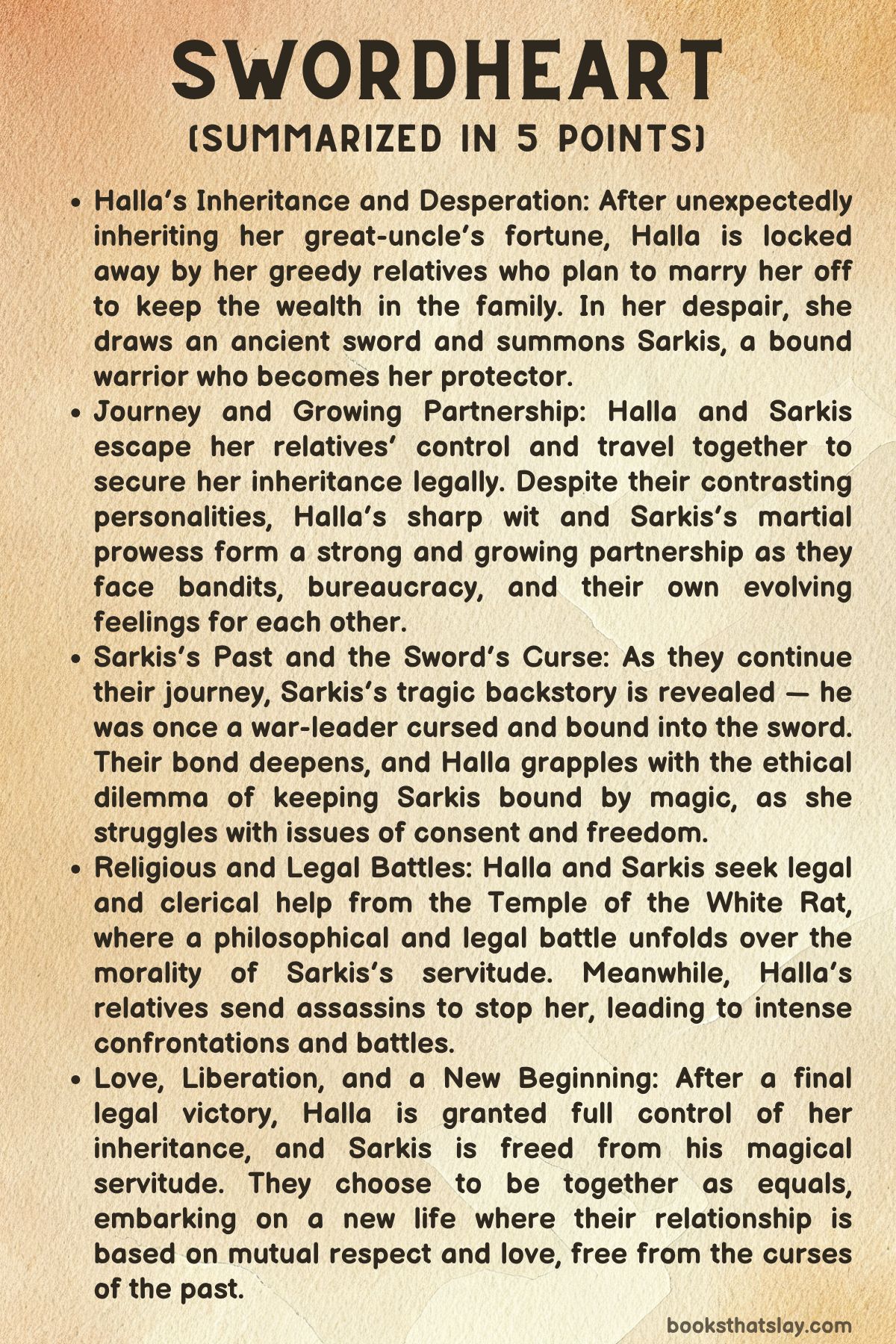

Swordheart by T. Kingfisher is a darkly comedic fantasy novel that follows the story of Halla, a widow who unexpectedly inherits a vast fortune from her great-uncle Silas.

However, this newfound wealth is more of a curse than a blessing, as it entangles her with manipulative relatives who wish to marry her off to her cousin, Alver, in order to secure the inheritance. As Halla struggles to escape her family’s oppressive grasp, she inadvertently summons Sarkis, a rugged and mysterious warrior bound to an enchanted sword once owned by her uncle. Sarkis becomes her unlikely protector, leading them both on a journey of survival, escape, and self-discovery, all while navigating the absurdities of their bizarre circumstances.

Summary

Halla of Rutger’s Howe never imagined that inheriting her great-uncle Silas’s vast fortune would become her worst nightmare. As a widow, she had hoped for peace and a quiet life, but her relatives see her newfound wealth as an opportunity to further their own agendas.

Halla quickly realizes that her family intends to marry her off to her cousin, Alver, not for love, but for financial gain. This idea is pushed by her manipulative Aunt Malva, who consistently pressures Halla into submission.

Feeling trapped and desperate, Halla contemplates suicide as the only way to escape her oppressive fate.

However, fate intervenes when Halla inadvertently summons Sarkis, a warrior bound to a magical sword that once belonged to her great-uncle. Sarkis appears in a flash of blue light, initially confusing Halla, who struggles to comprehend the sudden appearance of this gruff, rugged man.

Sarkis explains that he is bound to the sword and is sworn to protect whoever wields it. In this case, that person is now Halla.

Although she is initially hesitant, Halla soon realizes that Sarkis is her only hope for escaping her family and the unwanted marriage they are trying to force upon her.

As Halla’s relatives continue to push her into a corner, with Alver’s advances and Aunt Malva’s relentless pressure, Halla grows more desperate. Her frustration turns to action, and she makes the bold decision to escape.

This sets off a chaotic chain of events, leading to a violent confrontation with her family. In this moment of tension, Sarkis showcases his combat skills, easily dispatching the household guardsman, Roderick, and standing firm in his role as Halla’s protector.

Their escape is nothing short of absurd, with Halla reflecting on the surreal nature of her circumstances.

Despite the growing danger and absurdity of their situation, Halla begins to appreciate Sarkis’s steadfastness and strength. He is everything she is not—gruff, practical, and determined.

As they flee, Sarkis becomes more than just her protector; he becomes her only ally in a world that seems bent on crushing her. Together, they navigate the treacherous landscape of both the physical and emotional obstacles that come their way, with Halla learning to trust Sarkis more with each passing day.

The escape journey is not without its own set of challenges. Halla and Sarkis find themselves pursued by constables, alerted by her Aunt Malva’s dramatic cries for help.

The pair takes to the dark streets, trying to avoid detection by hiding in alleys and using clever distractions to evade capture. In a bittersweet moment, they pass through the churchyard where Halla’s great-uncle Silas is buried.

Although she never truly processed his death, the visit serves as a moment of reflection, as Halla struggles to come to terms with the complexities of her family and her inheritance.

Their journey leads them to even more bizarre encounters, with Sarkis, despite his warrior prowess, showing signs of injury from earlier scuffles. Along the way, Halla and Sarkis share a quiet moment of mutual understanding, where they briefly discuss their pasts.

Halla, still reeling from the emotional weight of her situation, feels a mix of guilt and resignation regarding her family. Sarkis, for his part, reflects on his own tortured past as a warrior bound to the sword, offering more insight into his complex and troubled nature.

The journey takes Halla and Sarkis into the treacherous Vagrant Hills, a place full of strange creatures, dangerous terrain, and shifting realities. Alongside them is a small group of allies, including Zale, a paladin who helps them navigate through the perils of the Hills.

As the group battles through these hazards, they also confront the weight of their past actions, including the accidental deaths of two individuals they had to hide. The tension escalates as Halla’s growing feelings for Sarkis add emotional complexity to their survivalist journey.

Their journey is fraught with near-death encounters and escalating tension, especially with the emergence of strange creatures and the haunting presence of the Motherhood, a faction of people who suspect Halla of consorting with demons. Sarkis, who has witnessed countless battles, is increasingly troubled by his immortality, especially as his attachment to Halla deepens.

At one point, Sarkis even considers sacrificing himself to protect Halla, believing that his death would secure her safety. However, Halla refuses to accept his self-destructive mindset, pushing him to confront his own vulnerability and feelings for her.

Meanwhile, Halla grapples with the growing emotional connection between them. She struggles to accept her feelings for Sarkis, particularly as she learns more about his tortured past and the emotional scars that come with being bound to a sword.

The bond they form is tested as they face challenges that put their lives at risk, but it also serves as a grounding force for both characters.

As they approach Amalcross, a place where they hope to find refuge, their situation becomes increasingly dire. Halla finds herself caught up in the tragic murder of a family friend, Bartholomew, and the dangerous pursuit of the sword by the scholar Nolan.

This sets off a series of events that force Halla to confront the darker side of magic, the sword’s power, and her own feelings for Sarkis. In a climactic moment, Halla holds Nolan at gunpoint, negotiating for the sword in a desperate bid to save Sarkis and restore some semblance of control over her life.

The narrative reaches a turning point when Sarkis, after a self-inflicted injury, finally emerges from the sword, now fully human. The reunion between him and Halla is emotionally charged, as they both grapple with the complexity of their bond.

Despite their tumultuous history, they find solace in each other’s arms, and Sarkis, now free from his magical bonds, proposes to Halla. Their engagement marks a new chapter in their lives, one that holds the promise of healing and reconciliation.

In the final chapters, the couple faces the societal pressures of marriage, with Halla’s reluctant acceptance of the concept of a “marriage price” rooted in her culture’s traditions. Despite the challenges, Halla and Sarkis find a way forward, agreeing to marry and solidifying their bond.

The story ends on a bittersweet note of uncertainty, leaving room for more adventures and mysteries to unfold as the couple prepares to face their future together. The epilogue hints at a second sword, raising questions about the past that will likely propel their story into the next chapter of their journey.

Characters

Halla

Halla, the central character of Swordheart, begins her journey as a woman burdened by the weight of familial expectations and disillusionment with her life. Widowed and emotionally drained, she unexpectedly inherits a large fortune from her great-uncle Silas, only to find herself ensnared by her manipulative relatives, particularly her Aunt Malva, who aims to force her into an unwanted marriage with her cousin, Alver.

This oppressive environment pushes Halla to the brink of despair, leading her to contemplate suicide as a means of escape. However, her life takes an unexpected turn when she summons Sarkis, the servant of a magical sword once owned by Silas.

Sarkis’s sudden appearance transforms Halla’s life, offering her both protection and an unpredictable ally.

Throughout the narrative, Halla’s character evolves significantly. Initially, she is a reluctant protagonist, unsure of how to navigate the magical, dangerous world into which she has been thrust.

Her sense of survival is contrasted with Sarkis’s more pragmatic approach, often creating tension between them. Despite her initial resistance, Halla begins to develop a deeper understanding of her own inner strength and the possibility of forging a new life away from the clutches of her family.

Her growth is further explored as she moves from a place of helplessness to one of agency, as she makes crucial decisions for her survival, often in collaboration with Sarkis. Halla’s complex emotions, including guilt, resentment, and a sense of deep loss regarding her family, add depth to her character, making her more than just a victim of her circumstances.

Sarkis

Sarkis, the rugged and emotionally complex warrior bound to a magical sword, stands in stark contrast to Halla’s vulnerability. His history as a warrior who failed in battle and was subsequently bound to the sword for centuries plays a significant role in shaping his character.

Sarkis’s internal conflict is one of the central themes of the narrative, as he grapples with his immortality and the immense emotional weight of his servitude. He longs for death, seeking an escape from his endless existence, but his growing feelings for Halla complicate this desire.

Sarkis is pragmatic, often taking the lead in their survival strategies, but he also carries a deep emotional burden, revealed through his reflections on past battles and the loss of his humanity. His interactions with Halla are marked by both tenderness and internal conflict, as he feels responsible for her safety but is also aware of the complicated nature of their bond.

As the story progresses, Sarkis’s development is marked by his increasing vulnerability, particularly in his emotional responses to Halla’s actions and their shared moments of closeness.

Sarkis’s role as Halla’s protector is central to the plot, yet his own desires for freedom and escape from his immortal existence create a sense of tension. His ultimate sacrifice—attempting to take control of his fate by falling on his sword—underscores his internal struggle, but it also acts as a pivotal moment in his relationship with Halla.

This emotional complexity, combined with his growing affection for her, makes Sarkis a deeply compelling character, torn between duty, desire, and a wish for release from the curse of his existence.

Zale

Zale, a practical and grounded character, plays an important role in the narrative, especially in his interactions with Halla and the rest of the group. As a paladin, Zale brings a sense of stability to the otherwise chaotic situation the group faces.

He is marked by his pragmatic approach to the dangers they encounter and is often seen acting as a moral compass in contrast to the more impulsive actions of others, particularly Halla. While he does not carry the same emotional weight as Halla or Sarkis, Zale’s role is crucial in maintaining a sense of order during the group’s journey, offering legal and moral support when needed.

His calm demeanor and strategic thinking make him an essential ally, though his own fears and uncertainties about the unpredictability of the world around them begin to surface as the group ventures deeper into dangerous territories.

Brindle

Brindle, the gnole, is one of the more eccentric characters in Swordheart, adding a sense of both humor and unpredictability to the story. His unconventional wisdom and unique perspective on the world provide moments of levity in an otherwise tense and dire situation.

Brindle’s loyalty to the group is unwavering, and despite his odd nature, he proves to be an invaluable companion. His leadership in guiding the group through the Vagrant Hills, a place fraught with dangers, showcases his resourcefulness and determination.

Though not as emotionally driven as the others, Brindle’s actions often highlight the importance of community and teamwork in their survival. His quirky nature and unwavering loyalty to his friends create a sense of camaraderie and add depth to the group dynamic.

Nolan

Nolan, the scholar who becomes an antagonist in Swordheart, represents the intellectual and manipulative forces at play in the narrative. His pursuit of the magical sword, and by extension his interest in Halla and Sarkis, exposes his selfishness and disregard for the emotional turmoil he causes in others.

Nolan’s motivations, driven by personal gain and the desire to control powerful forces, create a sense of danger and urgency for Halla, who must navigate not only her emotional bonds with Sarkis but also the external threats posed by figures like Nolan. His interactions with Halla push her into moral dilemmas and force her to confront the darker aspects of the world she is now a part of.

As a manipulator, Nolan represents the intellectual, calculated side of conflict, contrasting with the emotional and physical struggles of the other characters.

Alver and Aunt Malva

Alver and Aunt Malva represent the oppressive forces that Halla is trying to escape. Alver, the cousin who seeks to marry Halla to secure her fortune, is portrayed as repulsive and entitled, while Aunt Malva is the calculating and manipulative matriarch who seeks to control Halla for her own gain.

Together, they embody the societal and familial pressures that Halla has long endured. Their relentless attempts to pressure Halla into marriage form the basis of her initial desperation and drive to escape.

While they are not given as much narrative depth as the other characters, their presence is vital in establishing Halla’s initial motivations and her desire for autonomy.

Themes

Inheritance and Power Dynamics

The inheritance Halla receives from her great-uncle Silas becomes the cornerstone of the power struggles within her family. This theme explores how wealth, once thought to be a source of freedom and opportunity, can instead act as a mechanism of control, particularly when it comes to family dynamics.

Halla’s initial disillusionment with life only deepens as her relatives seek to use her newfound wealth to manipulate her into an arranged marriage. The money, which should theoretically grant Halla autonomy, instead tightens the hold of her family on her life.

Her relatives, especially Aunt Malva, act out of self-interest, using emotional manipulation and coercion to force Halla into submission, ignoring her own desires and independence. This power imbalance forces Halla into an unbearable position where her only choices seem to be acceptance of her fate or drastic measures to escape it.

The conflict surrounding Halla’s inheritance reflects a deeper commentary on how wealth can perpetuate cycles of oppression within families, where power is not just about financial control, but the ability to dictate the terms of personal freedom and autonomy.

Escape and Liberation

The theme of escape is central to Halla’s journey, beginning with her escape from her oppressive relatives and later from the dangers that constantly loom over her. From the moment she inherits the sword and is bound to Sarkis, her escape becomes a physical and emotional quest for liberation.

Halla’s struggles to break free from her relatives’ control mirror her internal battle to break away from the life she feels trapped in. The sword, with its magical powers and connection to Sarkis, symbolizes both an escape from her oppressive past and a potential key to her future.

Sarkis, though initially a reluctant and unconventional protector, becomes an unexpected ally in her fight for freedom. The emotional complexity of Halla’s escape lies not only in the external obstacles she faces but also in her internal conflicts—her reluctance to trust Sarkis, her feelings of guilt about leaving her family, and the pain of letting go of the life she knew.

Ultimately, the theme of escape transcends physical boundaries and becomes about emotional liberation, as Halla must learn to trust herself and her instincts to create a life beyond the manipulation and control of those around her.

Survival and Personal Growth

Survival in the world Halla and Sarkis inhabit is not just about physical endurance but also about psychological resilience and personal growth. As they journey together, facing everything from paladins to strange creatures, both characters undergo profound changes.

Sarkis, bound to a sword for centuries, has long since given up on the idea of survival, resigned to his immortality and the painful existence it entails. However, his connection to Halla, and the need to protect her, stirs something in him that he had long buried—his desire for agency, for freedom from the sword’s grasp.

Halla, on the other hand, starts as a woman on the brink of despair, but through her travels with Sarkis, she begins to reclaim her sense of self. Her experiences force her to confront not only external dangers but her own internal battles with guilt, fear, and hope.

Survival in this narrative is deeply intertwined with personal growth, as both Halla and Sarkis must reconcile their pasts and the mistakes they’ve made in order to move forward. This growth is not always linear and is often messy, with moments of doubt and setbacks, but it ultimately leads to a deeper understanding of themselves and each other.

Love, Loyalty, and Complicated Relationships

The relationship between Halla and Sarkis is marked by tension, complexity, and deep emotional turmoil. While the theme of love is apparent, it is not the conventional, idealized romance often seen in fantasy.

Instead, it is a raw and challenging connection that evolves as both characters navigate their individual traumas and the weight of their respective histories. Sarkis’s immortality and his bond to the sword make him a reluctant lover, and Halla’s own struggles with trust and independence complicate their relationship.

Yet, despite these barriers, their bond deepens over time as they begin to rely on each other for survival and emotional support. Loyalty, in this context, extends beyond mere affection—it becomes a matter of mutual dependence and a shared commitment to each other’s well-being.

This loyalty, however, is fraught with challenges, as Sarkis is ultimately bound to the sword and can never fully be free from it, while Halla must come to terms with the sacrifices and compromises that love demands. Their relationship highlights the tension between personal freedom and the emotional ties that bind people together, with both characters learning to navigate the complexities of love, sacrifice, and what it means to truly be loyal to another.

Mortality and Immortality

The contrast between mortality and immortality is a key theme in the story, particularly through the character of Sarkis. As an immortal warrior bound to a magical sword, Sarkis represents the curse of living forever without the ability to truly experience life.

His endless existence has made him weary, filled with regret and a longing for an end that never comes. In stark contrast, Halla, a mortal woman, is constantly reminded of the fragility of life, both in her family’s attempts to control her fate and in the dangers she faces on her journey.

The narrative uses this contrast to explore the implications of immortality—not as a gift, but as a heavy burden. Sarkis’s desire to die and end his suffering creates a tension with his role as Halla’s protector.

Meanwhile, Halla’s own journey is about finding meaning in a life that has been filled with loss and frustration, ultimately realizing that her life, though finite, is hers to shape. The theme of mortality versus immortality delves into the emotional weight of living, the desire for freedom, and the search for purpose, with both characters struggling to reconcile their views on life and death as they navigate their paths together.