The Bookstore Keepers Summary, Characters and Themes

The Bookstore Keepers by Alice Hoffman is a novel about the complexities of human relationships, memory, and healing. Set in a small, intimate town where the rhythms of life are shaped by the local bookstore, the story centers on the lives of those who are connected to this central place.

Through the lens of the bookstore’s keepers, we are drawn into a narrative that unfolds with a deep understanding of loss, personal growth, and the subtle threads that tie people together. Hoffman’s writing captures the delicate balance between the past and present, offering a narrative that explores how individuals come to terms with their stories and find their way forward in life.

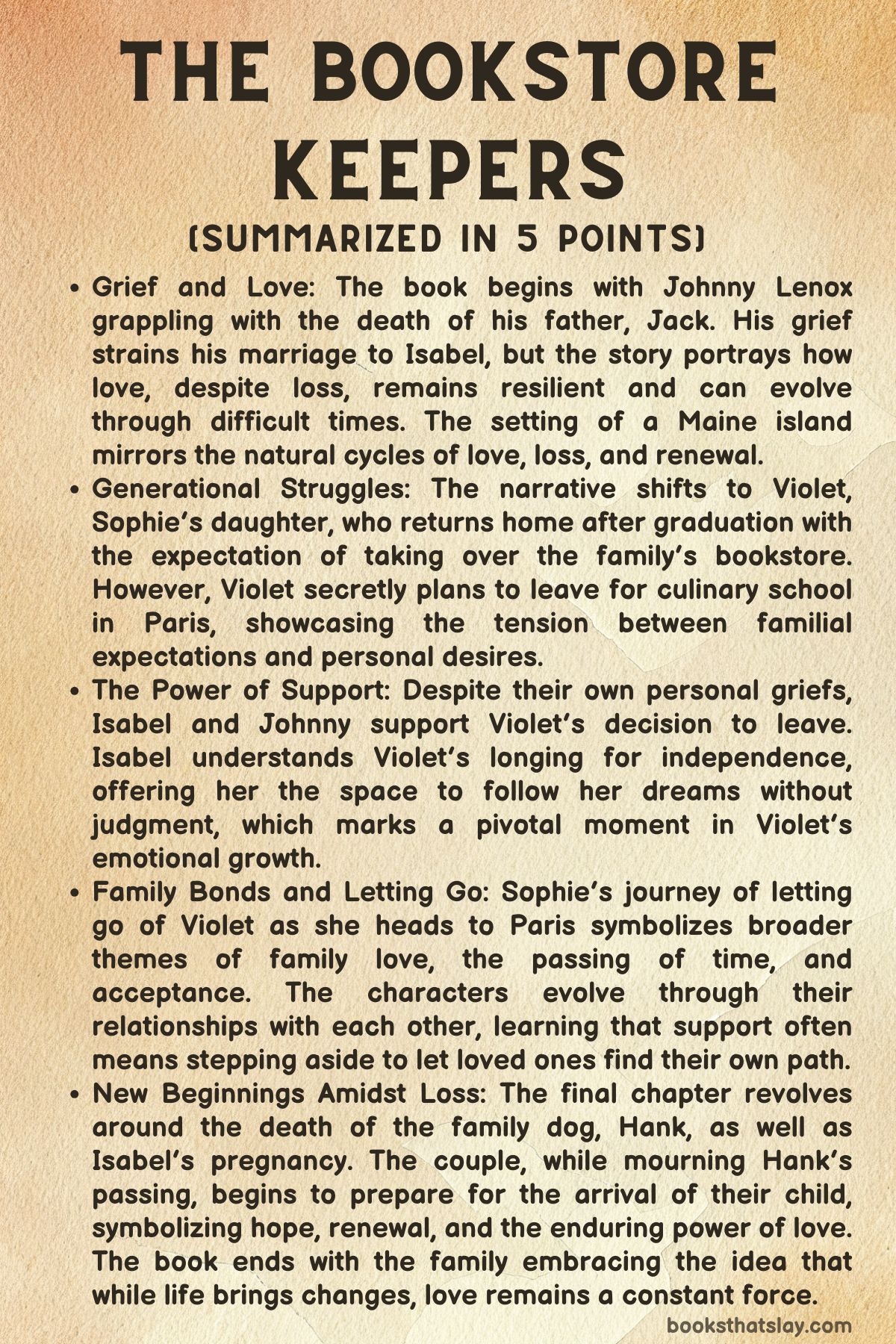

Summary

The story of The Bookstore Keepers revolves around a small town and the impact of its local bookstore, a place that not only serves as a source of knowledge and escape but also as a hub for the lives of its inhabitants. The narrative primarily focuses on the relationships between the keepers of this bookstore, their struggles, and how they work through the intricacies of their lives.

The central character is a woman named Margaret, who has spent much of her life in the quiet solitude of the bookstore. As a young girl, Margaret had been captivated by books, and her love for literature eventually led her to take over the small shop that had been in her family for generations.

Her bond with the bookstore is profound, and it serves as both a sanctuary and a source of strength for her. However, Margaret’s life is not as peaceful as it seems.

Beneath the surface, she is grappling with feelings of loss, especially the untimely death of her husband, Daniel. Daniel was a man of quiet strength, much like Margaret, and his absence has left a gaping hole in her life.

As Margaret deals with the aftermath of his death, she begins to notice subtle changes within the community and the bookstore itself. The shop, which had always been a place of comfort, starts to feel more like a place of isolation.

Margaret begins to question the role of the bookstore in her life and whether it is still a place of refuge or a reminder of what has been lost. In addition to her internal struggles, Margaret is also facing pressure from the community to sell the bookstore, as younger, more modern businesses begin to emerge, pushing the old ways aside.

Alongside Margaret, the story also follows her younger sister, Sophie, who returns to the town after living abroad for several years. Sophie has a complicated relationship with Margaret, marked by both love and rivalry.

Sophie’s return is a source of tension, as she has always felt overshadowed by Margaret’s calm, composed demeanor. Sophie’s life is filled with a sense of restlessness, and she is torn between her desire for a fresh start and her need to come to terms with her own past.

Sophie’s return to the bookstore reawakens old memories, and she is forced to confront the pain of her past decisions, particularly her estrangement from her family and the relationship she had with Daniel before his death.

As Margaret and Sophie’s paths intersect in unexpected ways, they find themselves drawn into a shared journey of emotional growth and healing. Margaret begins to see that the bookstore, and the memories associated with it, no longer hold the same power over her.

She realizes that while the bookstore was once a symbol of her past, it is also a place where she can begin to envision a new future. Margaret comes to understand that life, like the bookstore, is not static but constantly evolving.

Through Sophie’s return, Margaret also learns to reconcile with her own emotions, accepting the grief she has carried for so long and embracing the possibility of new beginnings.

The novel also introduces several other characters who are connected to the bookstore, each with their own stories and struggles. There is Peter, the quiet bookkeeper who has worked in the shop for years, and Rachel, a young woman who is new to the town and finds solace in the bookstore’s quiet atmosphere.

These characters bring their own depth to the story, reflecting the many ways in which people come to terms with their lives and their choices. The bookstore becomes a symbol of connection for these characters, a place where they can share their joys, sorrows, and dreams.

The novel concludes with a sense of resolution as Margaret makes peace with her past and the bookstore. She no longer feels the weight of her loss, and the shop, once a place of sorrow, becomes a symbol of renewal.

Sophie, too, finds peace with her choices and reconciles with her family. The story ends with a sense of hope, as the characters, despite their struggles, are ready to embrace the future and the new possibilities it holds.

The Bookstore Keepers is a beautifully written exploration of love, loss, and personal transformation. Through its richly drawn characters and the evocative setting of the bookstore, the novel offers a meditation on the ways in which we carry our pasts with us while also learning to move forward.

The narrative weaves together themes of family, healing, and the power of memory, making it a poignant and reflective read for those who appreciate stories of personal growth and connection.

Characters

Johnny Lenox

Johnny Lenox is the central character of More Than a Fish Loves a River, and his emotional journey is both poignant and transformative. As a ferry captain in a small island community, Johnny’s life has always been shaped by the rhythms of the sea and his deep connection to his father, Jack.

However, after Jack’s death, Johnny is thrown into a state of emotional turmoil. His grief, which he has never fully processed, becomes the driving force of his character arc.

The dream in which his father, disguised as an angel, bids him farewell marks the beginning of Johnny’s emotional unraveling. This experience forces him to confront the grief he has long avoided, as he realizes that his father’s death has left him with unresolved pain and a sense of abandonment.

Johnny is a man caught between two worlds—one tied to the past and one filled with uncertainty about the future. His relationship with his wife, Isabel, reflects his inner struggle.

Isabel’s return to him after years of separation offers a chance for reconciliation, but Johnny is unable to open up emotionally, withdrawing from her in his sorrow. His inability to process his grief also leads him to withdraw from his duties and his community, often seeking solitude to mourn in private.

Despite his pain, Johnny’s love for Isabel remains, and as they begin to rebuild their relationship, he learns the importance of patience and healing. Johnny’s character is defined by his struggle to reconcile the loss of his father with the possibility of a renewed future with Isabel, ultimately finding a sense of closure and emotional growth.

Isabel

Isabel, Johnny’s wife, plays a crucial role in his emotional journey. Having left Johnny years earlier, she returns to the island, offering a sense of stability and hope in the midst of Johnny’s grief.

Isabel is deeply concerned for Johnny, seeing the emotional distance that has grown between them since Jack’s death. While she offers him love and comfort, Isabel struggles with Johnny’s withdrawal and his inability to fully engage with her or their life together.

Her own emotional journey is marked by her own past grief, especially the loss of her mother, which parallels Johnny’s experience and gives her the emotional tools to understand his pain.

Isabel’s love for Johnny is steadfast, but her fear of losing him to his grief also makes her question their future together. As the story progresses, Isabel confronts the idea of loss once again, but this time with the possibility of new beginnings—most notably, the idea of having children together.

Isabel’s character growth is evident as she learns to let go of her fears, support Johnny through his grief, and rediscover the love they once shared. She ultimately becomes a symbol of patience, resilience, and the strength required to rebuild a life after loss.

Violet

Violet is Isabel’s niece, a young woman who returns to the island after graduating college. Her character mirrors Johnny’s in some ways, particularly in her struggle to balance her dreams with the expectations of her family.

Violet carries the burden of a secret: she plans to leave for Paris, which represents her desire to forge her own path independent of her family’s influence. Like Johnny, Violet must confront the idea of letting go—of her past, of the island, and of her family’s expectations.

Her decision to leave the island serves as both an act of liberation and a painful separation from those she loves.

Throughout the story, Violet’s internal conflict between family loyalty and personal aspiration provides an emotional counterpoint to Johnny’s grief. Her character arc explores themes of independence, self-discovery, and the complexities of family relationships.

As Violet prepares to leave, Isabel grapples with the fear of losing her, mirroring the tension Johnny feels about his own future. Violet’s journey is one of self-empowerment and reconciling her desires with the realities of her family’s needs and emotions.

Hank

Hank, the old dog, serves as a quiet but significant presence in the story. Though he is not as central as the human characters, Hank’s role as a companion to Johnny is essential in highlighting the emotional landscape of Johnny’s grief.

As an animal that has shared Johnny’s life for many years, Hank represents the steady and enduring love that has been a constant in Johnny’s life. While Hank cannot speak or offer counsel, his presence offers Johnny comfort and serves as a reminder of the simpler joys of life.

His steady companionship offers a grounding force for Johnny, helping him to remember that, even in the midst of profound loss, there are still things worth holding on to.

Jack Lenox

Though Jack Lenox is deceased before the story begins, his influence looms large over the narrative. As Johnny’s father, Jack represents both the stability and the emotional turmoil that Johnny faces.

Jack’s death leaves a deep hole in Johnny’s life, and his emotional absence is a key source of Johnny’s grief. Through the dream in which Jack appears as an angel, the reader is given a glimpse of the unresolved issues between father and son.

Jack’s role in the story is both symbolic and emotional, as he represents not just the past but also the need for closure and healing. His death, while initially seen as an abandonment, ultimately serves as a catalyst for Johnny’s personal growth and transformation.

Themes

Grief and Healing

In More Than a Fish Loves a River, grief serves as a central theme, deeply influencing the emotional journeys of the characters, particularly Johnny. His grief over the death of his father, Jack, shapes much of the narrative, creating an emotional chasm that isolates him from his wife, Isabel, and his community.

Johnny’s struggle with unresolved grief manifests in his withdrawal from those around him, a reflection of his internal battle with the loss he has not fully processed. The profound emotional distance that grows between Johnny and Isabel highlights how grief can distort relationships, turning even the closest bonds into sources of tension and misunderstanding.

As Johnny experiences a spiritual visitation from his father, the narrative explores how grief can sometimes manifest as dreams or memories, serving both as a reminder of the past and as a challenge to move forward. Johnny’s journey is one of confronting this grief, recognizing its hold over him, and gradually finding a way to live with the loss.

The eventual resolution of his emotional turmoil, symbolized by his growing relationship with Isabel and the promise of a new life, underscores the healing power of time, patience, and emotional openness. Through Johnny’s experience, the novel explores grief not as a singular event but as an ongoing process of transformation and acceptance.

The Complexity of Family Relationships

Family dynamics are at the heart of the narrative, providing both the source of tension and the foundation for growth. Johnny’s strained relationship with his father, marked by unresolved feelings of abandonment, is a key element of the story.

His father’s death leaves Johnny with a sense of emptiness that he cannot easily fill, and the unresolved issues between them become a silent force that shapes his emotional state. Isabel, too, struggles with her own familial past, particularly the grief she experienced when her mother passed away.

These personal histories add depth to her relationship with Johnny, as she must navigate her own pain while trying to offer him comfort. The arrival of Violet, Isabel’s niece, adds another layer to the theme of family, as Violet’s own struggles with her family’s expectations and her desire to forge an independent path mirror Johnny’s emotional turmoil.

The narrative weaves these various threads of family together, highlighting how personal histories and unresolved conflicts can complicate even the most loving relationships. Yet, despite these complexities, the novel suggests that family, while often a source of pain, is also a space for healing and transformation.

The eventual reconciliation between Johnny and Isabel points to the possibility of forgiveness and understanding, even when the past is fraught with difficulty.

The Search for Identity and Transformation

The theme of personal transformation runs throughout More Than a Fish Loves a River, particularly in Johnny’s journey from grief to acceptance and self-understanding. Johnny’s identity is heavily tied to his role as a ferry captain and the rhythms of life on the island, yet the death of his father disrupts his sense of self and his purpose.

As he grapples with his grief, Johnny is forced to confront aspects of his identity that he has long ignored or avoided. His emotional withdrawal, the physical distance he places between himself and those he loves, reflects his inner conflict and the difficulty of accepting change.

The idea of transformation is also embodied in Violet, who, like Johnny, must confront her past and make difficult decisions about her future. Violet’s departure for Paris symbolizes a break from the expectations of her family and a bold step toward carving out her own identity.

Through both Johnny and Violet, the novel explores how personal transformation often requires letting go of the past and facing the discomfort of change. In this way, the story presents identity not as a fixed concept but as something that evolves over time, shaped by both personal choices and the external forces of family, loss, and love.

Love and Renewal

Love, despite its complexities and challenges, serves as a force of renewal in More Than a Fish Loves a River. Johnny and Isabel’s relationship is marked by both deep affection and significant tension, with the shadow of Johnny’s grief threatening to tear them apart.

However, their shared love acts as a catalyst for healing, allowing them to slowly rebuild their bond over time. The possibility of having a child together becomes a symbol of hope and renewal, suggesting that love, even after loss, can lead to new beginnings.

The novel suggests that love is not an easy or perfect force—it is often fraught with pain, misunderstandings, and sacrifices—but it is enduring and capable of providing the strength needed to move forward. In the context of family, love becomes a unifying force, bridging the emotional distances between characters and providing a source of comfort during times of hardship.

The ending of the story, with Johnny and Isabel prepared to welcome their child, reflects the theme of love’s capacity for renewal and its power to overcome past pain. Through the lens of love, the novel explores the transformative nature of relationships, where personal growth and healing are often facilitated by the connections we share with others.