A Gorgeous Excitement Summary, Characters and Themes

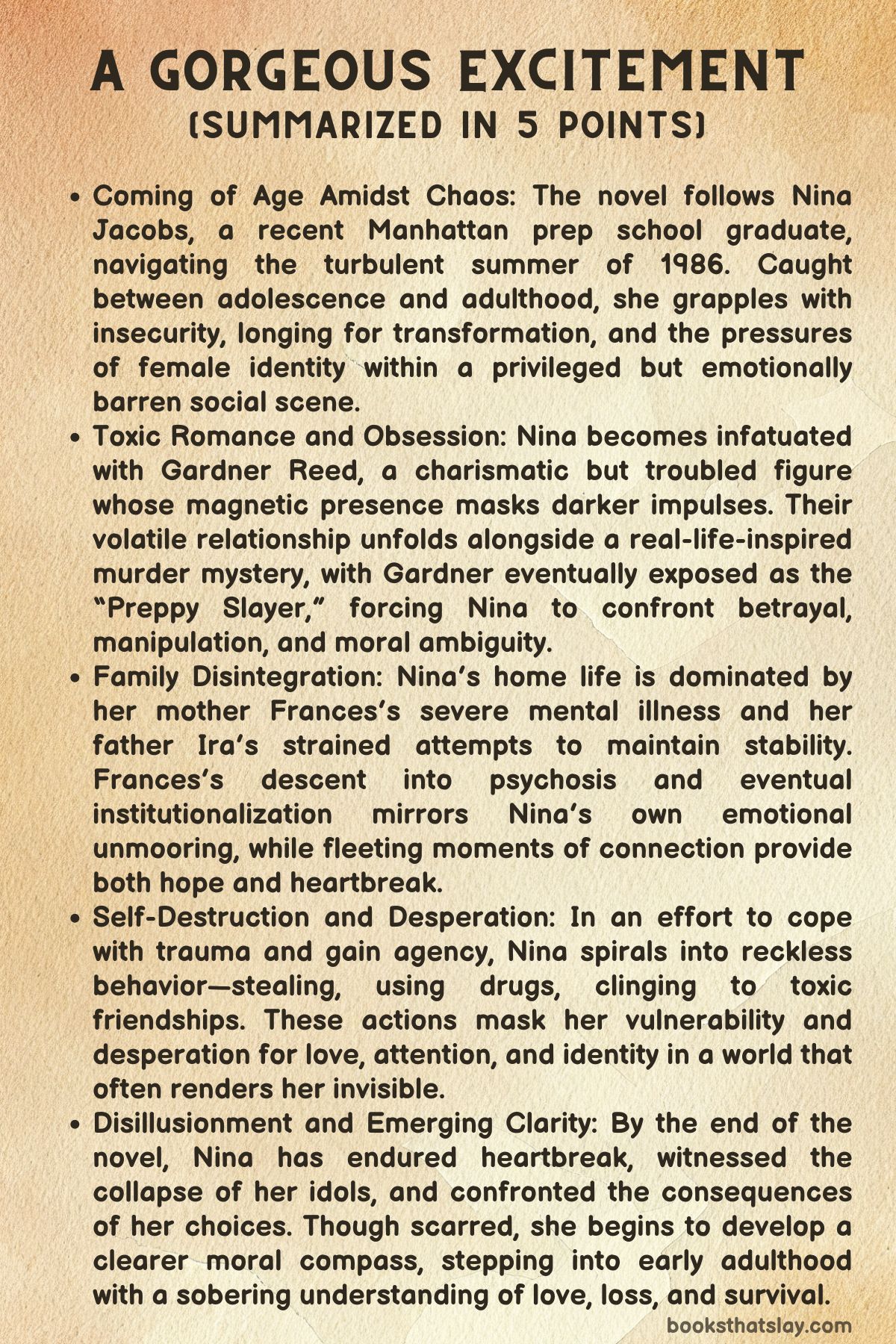

A Gorgeous Excitement by Cynthia Weiner is a psychological coming-of-age novel set against the glittering, dangerous backdrop of 1980s New York City. The story follows Nina Jacobs, a smart but emotionally fragile young woman fresh out of college, who yearns to shed the weight of her chaotic home life and construct an identity grounded in independence, allure, and experience.

As Nina explores adulthood through reckless friendships, risky relationships, and family turmoil, she is drawn into a world where power, desire, and violence blur. The novel unflinchingly examines how privilege shields some while destroying others, and how one girl’s search for control forces her to confront the most painful truths about herself and the people she trusts.

Summary

The novel opens in the summer of 1986 with a brutal murder in Central Park, setting a tone of privilege shadowed by violence. A young woman has been killed, and the accused is Gardner Reed, a rich and well-connected socialite.

Public opinion quickly bends in his favor. The victim is painted as sexually aggressive and foolish, while Gardner is seen as a victim of unfortunate circumstance.

This troubling narrative of victim-blaming and elite protectionism is the backdrop for Nina Jacobs’s story—a 22-year-old recent graduate from Bancroft trying to reinvent herself and find freedom.

Nina lives with the psychological remnants of growing up with Frances, her mentally ill, melodramatic mother, and Ira, her well-meaning but passive father. Her home is a place of volatility masked by moments of intimacy.

At her graduation, Frances causes a scene that reminds Nina of the emotional instability she longs to escape. Determined to be seen as adult and desirable, Nina spends her nights in Manhattan bars with her privileged yet cruel friends, Leigh and Meredith, and dreams of being recognized by someone like Gardner Reed.

Her failed sexual encounter with Walker Pierson becomes a humiliating anecdote among her peers, highlighting her insecurity and the gendered scrutiny she faces.

As Nina stumbles into a new friendship with Stephanie—a bold, brash, and emotionally unpredictable young woman—her world begins to shift. Stephanie exudes the confidence Nina envies, and their bond deepens over cigarettes, family secrets, and cocaine.

Nina sees in Stephanie a model for how to navigate the city with fearlessness, even if that fearlessness sometimes slips into recklessness. Meanwhile, Gardner reappears in Nina’s life, flirtatious and elusive.

Though he has a glamorous girlfriend, Holland, Gardner pays attention to Nina, which electrifies her. She becomes infatuated, building a romantic fantasy around fleeting moments of connection.

Throughout her adventures with Stephanie and entanglements with Gardner, Nina also grapples with her relationship with her mother. Frances’s moods swing wildly—sometimes lucid and engaged, other times frenzied and detached.

Ira tries to maintain normalcy, but his distance forces Nina into the role of emotional caretaker. Her longing for stability at home contrasts with her willingness to take risks in the outside world.

This duality becomes more pronounced as she follows Gardner into increasingly wild and chaotic experiences. Their night at the Carlyle Hotel, where they do cocaine, vandalize a luxury apartment, and teeter on the edge of romantic and criminal disaster, marks a moment of both triumph and self-betrayal for Nina.

She finally feels chosen, but also profoundly out of control.

As the summer progresses, Nina’s relationships start to reveal their dark undercurrents. Gardner’s charm begins to crack.

He is shown to be reckless, manipulative, and emotionally detached. His behavior grows erratic, and when Alison—a girl from their social circle—is found dead, suspicion falls on Gardner.

His friends rally around him, painting Alison as unstable and oversexed. Nina watches in horror as they reduce Alison to a cautionary tale, defending Gardner with the same language once used to justify the murder in the park.

This misogynistic defense of male privilege forces Nina to confront her own silence, her own complicity in believing the narratives spun by power.

Stephanie’s world also begins to destabilize. Her boyfriend Patrick grows possessive and cruel, while her confidence frays under emotional strain.

Nina witnesses these changes with growing concern, even as her own emotional stability falters. A late-night encounter with Meredith reveals the fragility of their entire social group.

Meredith, once confident and cutting, confesses to a recent AIDS scare, revealing the fear and vulnerability masked by their performative adulthood.

Frances, meanwhile, swings between recovery and collapse. Her brief return to domestic life—joking, cooking, even buying Nina gifts—fills Nina with cautious hope.

But it doesn’t last. Frances’s manic energy soon spirals, culminating in a public outburst at Stephanie’s workplace that humiliates and worries Nina.

The burden of family weighs heavily on her, just as her social life becomes more toxic.

The emotional climax comes in the wake of Alison’s death. Nina attends a gathering at Flanagan’s, where Gardner’s friends cling to denial.

When Gardner’s interview from jail is read aloud, he blames Alison, implying self-defense against her aggressive sexuality. The room accepts his version easily, and Alison is posthumously slut-shamed.

Nina is enraged, not only at Gardner but at herself for having ever wanted him to choose her. A surreal dream, in which she sees Gardner and Alison frozen in time beneath a tree, signals her internal reckoning with what she’s been trying to deny: Gardner may be guilty, and she may have ignored the signs.

The final act brings Nina face-to-face with the truth. She visits Gardner’s apartment, hoping for answers, and instead finds a room covered in mutilated Polaroids of Alison.

It is a moment of visceral horror and clarity. Gardner is not just reckless—he is dangerous.

The fantasy shatters, and Nina flees, realizing that the man she wanted was built of illusions. Her silence, her longing, her need to be seen—all of it has led her to this unbearable truth.

By the end of the novel, Nina has changed. She is still vulnerable, still navigating grief and confusion, but she has seen through the lies.

The layers of privilege, power, and denial that protect men like Gardner can no longer hide the truth from her. Her transformation is not marked by triumph but by knowledge—painful, irrevocable, and necessary.

She steps into adulthood not with clarity or confidence, but with the awareness that innocence and complicity often go hand in hand, and that growth sometimes begins with the courage to face what one most wants to forget.

Characters

Nina Jacobs

Nina Jacobs serves as the deeply introspective and emotionally turbulent heart of A Gorgeous Excitement. She is a recent graduate from Bancroft, a prestigious institution, but instead of basking in her academic success, Nina is shadowed by profound personal insecurities, a volatile home life, and a complicated desire for sexual and emotional awakening.

Her mother, Frances, suffers from a severe mental illness, oscillating between depressive episodes and manic energy, and Nina has spent much of her youth managing the unpredictable emotional landscape at home. Her father Ira, though loyal, is passive in the face of Frances’s volatility, unintentionally placing the emotional burden of caregiving on Nina.

These family dynamics leave Nina emotionally raw and searching for a new identity—someone more glamorous, more independent, more adult.

Throughout the novel, Nina’s internal conflict takes center stage as she attempts to navigate the boundaries between girlhood and womanhood, danger and desire, vulnerability and power. Her attempts to transform—through parties, substance use, and relationships—are driven by a need to reclaim control over her body, her image, and her narrative.

However, her search is fraught with contradiction. She is painfully self-aware, yet easily swayed by those who exude charisma or confidence.

Her flirtation with Gardner Reed becomes emblematic of this struggle; he embodies both her fantasies and her fears. As Nina becomes more enmeshed in a world of emotional chaos, reckless friendships, and destructive lust, her arc shifts toward disillusionment.

By the end, following the harrowing death of Alison and the exposure of Gardner’s true nature, Nina is left altered—grappling with guilt, rage, and a sobering sense of adulthood born not from freedom but from grief and clarity.

Gardner Reed

Gardner Reed is a magnetic, dangerous presence throughout A Gorgeous Excitement, operating as both a symbol of freedom and a harbinger of destruction. He belongs to the elite social world of New York—wealthy, admired, untouchable—but is also defined by his rebellion against its conventions.

Gardner is enigmatic, effortlessly cool, and socially fluent, the kind of figure who seems to hover above consequence. To Nina, he is the incarnation of desire and adventure: someone who sees her, touches her, invites her into a world that promises transformation.

His flirtations, cocaine binges, and illicit escapades all reinforce his aura of thrilling risk.

But beneath the surface glamour lies something far more sinister. Gardner’s charm is undercut by deep instability and narcissism.

He is manipulative, self-absorbed, and ultimately violent. His behavior escalates from party antics to the grotesque—culminating in Alison’s death and his cold, self-exonerating narrative that paints her as the aggressor.

Gardner represents the toxic legacy of privilege: someone who weaponizes his charm and social standing to evade accountability. His descent is not sudden but incremental, masked by beauty and bravado until Nina, and others around him, can no longer ignore the truth.

By the end of the novel, Gardner is a tragic yet terrifying figure—a boy corrupted by entitlement and unacknowledged darkness.

Frances Jacobs

Frances, Nina’s mother, is an erratic and often overwhelming force in A Gorgeous Excitement. Suffering from severe mental illness, she fluctuates between depressive withdrawal and euphoric bursts of energy.

Her behavior veers into the theatrical—meltdowns, wild declarations, and public outbursts—but these episodes are underpinned by genuine emotional fragility. Frances’s illness casts a long shadow over Nina’s life, shaping her daughter’s hyper-awareness, emotional caution, and fierce desire for control.

Yet, Frances is not simply a burden. She is witty, loving, and in certain lucid moments, deeply insightful.

These moments of warmth and maternal clarity, though brief, offer glimpses of the woman she could be without the illness.

Their relationship is one of painful co-dependence. Nina both resents and loves her mother, fears her instability yet longs for her affection.

Frances’s unpredictability becomes a constant emotional backdrop that makes Nina wary of trusting stability or permanence. Her sudden moments of recovery—helping around the house, joking with Ira—offer hope, only to crumble under the weight of another episode.

In the end, Frances represents both the tenderness and terror of maternal love warped by illness, and her presence in Nina’s story is a poignant reminder of the inescapable influence of family history.

Stephanie

Stephanie functions as Nina’s counterpart and sometimes catalyst—a brash, confident young woman who lives with uninhibited flair. Introduced through a serendipitous conversation, Stephanie quickly becomes an intoxicating presence in Nina’s life.

She exudes a kind of defiant coolness that Nina both envies and gravitates toward. Stephanie smokes, parties, speaks her mind, and seems immune to judgment.

Her confidence masks a complex inner life, including difficult romantic entanglements and a sharp awareness of social hypocrisies, especially in male-dominated spaces. Stephanie offers Nina a glimpse into a more liberated self, serving as both role model and mirror.

Their friendship is dynamic, intense, and occasionally fraught with unspoken competition or misunderstandings. Stephanie’s relationship with Patrick reveals cracks in her facade; she is not as invincible as she appears, and Nina slowly learns that boldness can be a defense as much as a trait.

When Alison dies and Gardner is arrested, Stephanie becomes one of the few people Nina can lean on—a figure of emotional consistency in a world unraveling. Through Stephanie, the novel explores female friendship as a site of both solidarity and self-discovery.

Ira Jacobs

Ira, Nina’s father, is a quiet, well-meaning figure who struggles with emotional passivity. He loves both Nina and Frances, but his love is expressed through endurance rather than intervention.

Ira tends to accommodate Frances’s episodes instead of challenging them, often placing Nina in the position of emotional mediator. His avoidance and desire to maintain harmony make him sympathetic but frustrating.

He represents the emotional stagnation that Nina longs to escape. Still, Ira is dependable and kind, providing a stabilizing, if insufficient, presence in Nina’s tumultuous world.

His arc is less about change and more about consistency—serving as a foil to Frances’s volatility and Gardner’s chaos.

Meredith

Initially depicted as superficial and aloof, Meredith gradually reveals layers of vulnerability that challenge Nina’s assumptions. Their relationship, once marked by passive-aggressive remarks and social power plays, deepens after Meredith’s AIDS scare, which brings raw human fear and desperation to the surface.

Meredith’s breakdown in the bathroom marks a turning point in Nina’s understanding of the people around her—revealing that even the most polished personas hide dread and insecurity. Meredith is emblematic of the novel’s larger theme: the fragility beneath youthful bravado, and the shared emotional terrain women navigate in a culture steeped in judgment, danger, and loss.

Themes

Power and Privilege

In A Gorgeous Excitement, the theme of power and privilege emerges with chilling clarity through the treatment of violence, justice, and public perception. The novel opens with the murder of a young woman in Central Park, a brutal crime quickly cloaked in narratives that protect the elite suspect and erase the humanity of the victim.

The accused is not just a man, but a figure of inherited power—wealthy, socially adored, and institutionally protected. His world bends public sympathy in his favor, allowing his peers, the media, and the justice system to rewrite the story as one of misunderstood sexuality or a tragic mistake.

In contrast, the victim is cast aside, her life reduced to hearsay and sexual innuendo. This disparity highlights how privilege operates as a shield, reshaping not just legal outcomes but cultural memory.

Nina, the protagonist, is keenly aware of how power determines visibility and credibility. Even in social interactions, she sees how charm and legacy insulate certain men while women are expected to be cautious, pleasant, and silent.

Gardner Reed, too, embodies this dangerous immunity—his behavior, increasingly erratic and destructive, is constantly forgiven or romanticized until the evidence becomes impossible to ignore. Nina’s complicity in this system is unintentional but real; her silence at Flanagan’s, her idolization of Gardner, and her reluctance to challenge misogynistic groupthink all stem from an understanding that power, once questioned, can be merciless in its retaliation.

Through these moments, the novel forces the reader to confront how systems of privilege rely not only on the powerful but on the acquiescence of those surrounding them.

Sexuality and Risk

Throughout the narrative, Nina’s journey toward sexual self-discovery is inextricably tied to risk, shame, and social consequence. Her desire to shed her virginity is not solely rooted in physical longing but in a belief that it marks adulthood, autonomy, and transformation.

However, each sexual or romantic interaction is shadowed by uncertainty, self-doubt, and the looming threat of judgment. Her failed encounter with Walker becomes social ammunition for her friends, who weaponize her vulnerability to assert dominance.

Even her most exciting moments with Gardner are tinged with unease—his attention is thrilling, but always just beyond her grasp, existing more in fantasy than reality. Nina often seeks validation through flirtation and reckless choices, walking alone at night or engaging in drug-fueled adventures not simply for pleasure, but to test the boundaries of control and desire.

These experiences are not liberating in a straightforward way; rather, they expose the complexity of female sexuality in a culture where young women are hyper-visible and yet perpetually at risk. Gardner’s eventual violence toward Alison—and the group’s vile justifications of it—crystallizes the danger lurking behind romanticized male aggression.

Nina’s evolving understanding of her own body, boundaries, and desires becomes a mirror for larger questions about consent, performance, and the thin line between wanting to be seen and being consumed. In the end, sexuality in the novel is never neutral or purely intimate—it is always refracted through the gaze of others, shaped by cultural scripts, and haunted by the possibility of harm.

Coming of Age in Chaos

Nina’s coming of age is not marked by milestones of confidence or clarity but by a series of emotionally dissonant events that reveal the instability of the world she inhabits. Her journey is defined by contradiction—she yearns to be seen but fears being judged, seeks rebellion but craves safety, experiments with risk but desires structure.

The city around her—New York in the 1980s—is both a playground and a battlefield. Parties, bars, and spontaneous adventures offer freedom, but they also expose her to manipulation, substance abuse, and emotional betrayal.

Even friendship is unreliable. Leigh and Meredith, once trusted companions, frequently undercut her, while Stephanie’s flamboyant charisma sometimes conceals deeper insecurities.

Nina is constantly negotiating who she is supposed to be versus who she actually is. Her mother’s mental illness adds to the chaos, pulling her into adult responsibilities far before she is ready, while her father’s passivity offers little refuge.

Her encounters with Gardner and her passive navigation of his increasingly destructive behavior highlight how coming of age can often mean confronting the failure of your heroes. It’s not just about discovering love or independence; it’s about losing illusions, managing grief, and learning how to function in a world that rarely offers easy answers.

Nina’s growth is incremental and painful, shaped less by epiphanies than by cumulative loss and disillusionment. The novel doesn’t glorify transformation—it reveals how growing up often means surviving a series of personal earthquakes and figuring out what pieces are left standing afterward.

Complicity and Silence

Silence becomes a moral force in the novel, shaping outcomes as powerfully as action. Nina often finds herself trapped between knowledge and expression, caught in the paralyzing middle ground of inaction.

When Gardner’s role in Alison’s death becomes public, Nina’s initial instinct is not to protest but to observe—to register her disgust quietly while allowing others to shape the narrative. Her silence is not rooted in approval but in fear, uncertainty, and the internalized sense that speaking up would be futile or dangerous.

This silence is shared across the novel’s landscape: friends remain quiet about red flags, society turns away from uncomfortable truths, and institutions gloss over abuses of power. Yet the consequences of this quiet are severe.

Alison’s memory is defiled by rumors and slut-shaming, and Gardner’s defenders grow louder as those who doubt him retreat into private discomfort. Nina’s dream about Gardner and Alison living in a diorama reflects her wish to freeze time, to process what cannot be undone.

But it also represents how silence encases people—locking them into roles and narratives they cannot escape. The theme of complicity forces readers to question how moral responsibility is shared, especially among bystanders.

Nina’s eventual horror at Gardner’s apartment—filled with disturbing Polaroids—marks a shift from silent disbelief to undeniable recognition. Her flight from that scene is not just physical but psychological; it signifies the collapse of denial.

By facing the truth, she begins to understand that silence is not neutral—it is often the language of power itself, sustaining the very injustices it seeks to avoid.