Blob by Maggie Su Summary, Characters and Themes

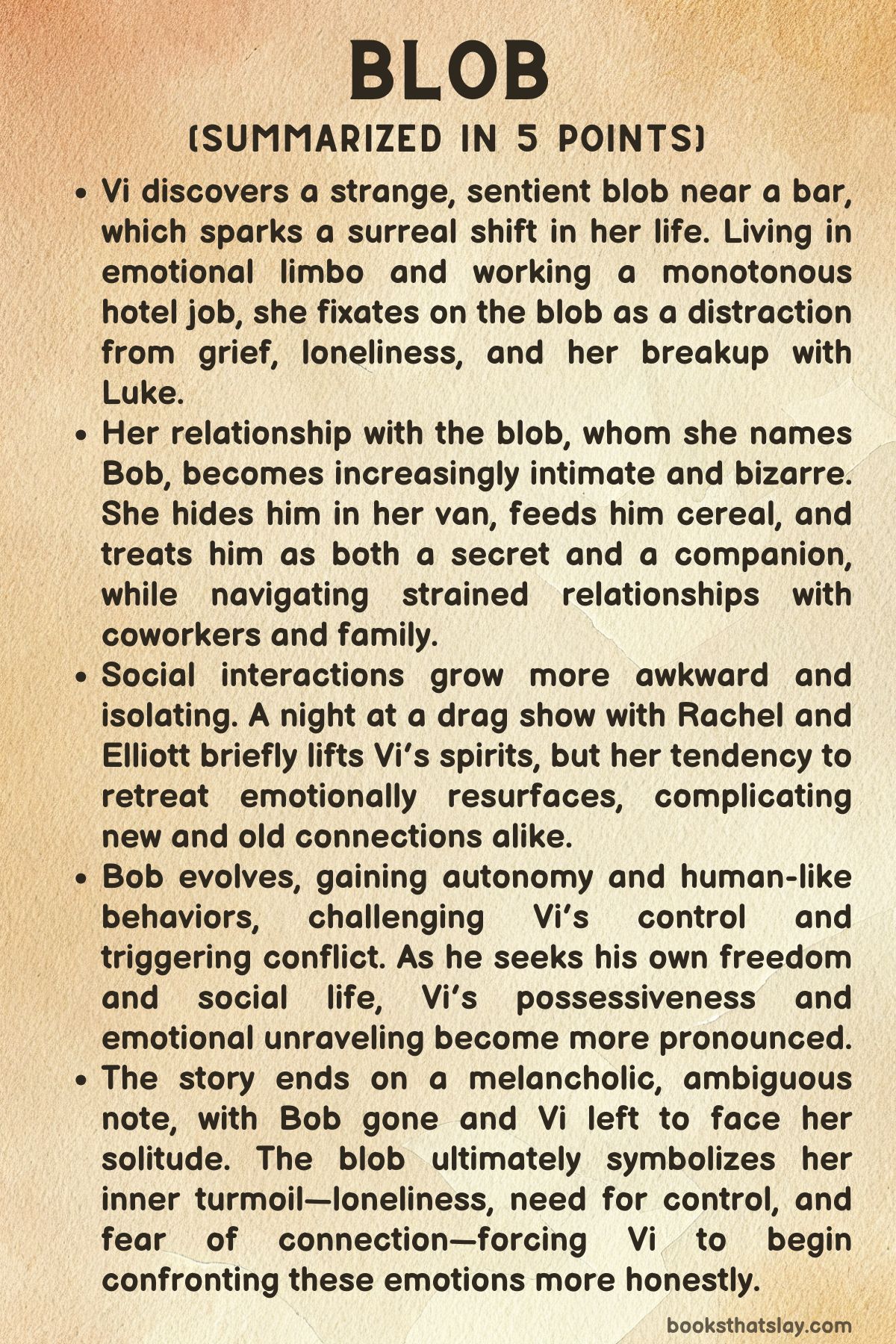

Blob by Maggie Su is a surreal, emotionally charged coming-of-age novel that centers on Vi, a disaffected young woman whose journey through grief, shame, identity, and self-acceptance takes an unusual form—her bond with a gelatinous, sentient blob she names Bob. The narrative slips fluidly between Vi’s childhood trauma, cultural alienation, and adult loneliness, using absurdity and magical realism to explore the limits of control, desire, and transformation.

Through Bob, a creature who slowly takes on human form, the novel examines how love, guilt, and autonomy coexist in uneasy tension, ultimately tracking Vi’s slow, painful evolution toward self-forgiveness and renewal.

Summary

Vi, a young college dropout drifting through life, finds an amorphous creature outside a dive bar in her Midwestern town. The creature—a blobfish-like gelatinous form she names Bob—becomes an unexpected anchor in her otherwise disoriented world.

Vi lives a monotonous life working at the Hillside Inn & Suites, quietly comparing herself to her cheerful and polished coworker Rachel, while coping with memories of her ex-boyfriend Luke and her estranged family. Bob quickly grows in importance, offering Vi a strange sense of companionship and a receptacle for her unspoken emotions.

Though absurd in appearance, Bob becomes a catalyst for Vi’s emotional unraveling and reassembly.

Vi’s attachment to Bob deepens, and she brings him home, hiding him from her parents during an uncomfortable family dinner where she discovers her childhood home has been sold without her knowledge. Bob slowly exhibits signs of sentience—blinking, reacting, and eventually communicating—blurring the boundary between pet, companion, and something more intimate.

This surreal bond leads Vi to confront haunting memories, such as abandoning her pregnant best friend in high school and the gnawing sense that her presence has always caused damage. Her loneliness, guilt, and desire for control manifest in her nurturing and shaping of Bob, who becomes a living reflection of her internal world.

Flashbacks reveal formative moments in Vi’s adolescence, especially a sweltering summer at age twelve. Isolated in her family’s attic, Vi discovers romance novels and the solitary comfort of masturbation, which immediately triggers shame.

These books promise transformation and romantic rescue but also embed harmful ideas about desirability, virginity, and self-worth. These early experiences intertwine with the racial isolation she faces as a biracial Asian girl—her white mother’s dismissal of her identity, a racial slur from a crush, and her brother’s distancing from his heritage—all of which add to Vi’s self-consciousness and fragmented sense of self.

Bob, meanwhile, is slowly changing from a formless blob into a humanoid figure, increasingly learning from Vi and mimicking the world around him. As he becomes more capable and independent—developing speech, limbs, and preferences—Vi’s control over him wanes.

She vacillates between caring for him and needing him to remain passive, childlike, and entirely hers. The emotional complexity of their relationship intensifies when Bob shows signs of sexual curiosity, particularly after watching pornography.

Vi is disturbed by his growing autonomy and responds by trying to restrict him, including physically restraining him in a misguided attempt to regain dominance.

Her control further unravels when Bob follows her to work and begins forming connections with others, especially Rachel, triggering Vi’s jealousy and fear. Simultaneously, Vi agrees to pose as her friend Elliott’s girlfriend during a family event, but the act ends in humiliation when she drunkenly kisses a cousin, provoking Elliott’s public rejection.

When she returns home, she finds Bob has escaped after breaking free from the restraints she used to contain him. The apartment is flooded, a metaphor for the emotional chaos she has tried and failed to suppress.

Desperate and spiraling, Vi seeks refuge in her parents’ home. For a time, the domestic simplicity—the garden, the food, the quiet—soothes her.

But even there, she is reminded she cannot live in stasis. Her parents gently nudge her to return to her life, leaving her no choice but to face the wreckage.

As she attempts to clean her apartment, Rachel reaches out with shocking news: she has found Bob and taken him in. When Vi visits them, she discovers Bob now dressed in Rachel’s style, fully immersed in a life Vi no longer controls.

Rachel and Bob are now romantically involved, and neither acknowledges Vi’s past connection to him.

Vi tries to reclaim Bob by revealing the truth—that he isn’t human, that she created him—but it’s too late. Rachel refuses to believe her, and Bob doesn’t deny it.

Bob, once dependent and docile, now chooses his own path, even if that path includes living within someone else’s vision of him. Defeated, Vi walks away, emotionally shattered.

Her descent into isolation becomes literal as she retreats into her apartment, turning into a “blob” herself. She ignores messages, lets her hygiene slip, and withdraws from the world entirely.

When her landlord mistakes her for a pet curled under a blanket, the moment is absurd but also transformative. It jolts her into action.

She brushes her teeth, flosses, and listens to an old voicemail from Luke, realizing his emotional detachment no longer holds power over her.

Determined to change, Vi begins to reclaim her agency. She decides to return to college—not for the major she abandoned, but for photography, the only class that ever truly resonated with her.

This decision is quietly radical: not driven by shame, obligation, or a need to prove herself, but by a desire to rebuild something from her brokenness. By the end, she begins to emerge—not fully healed or whole, but capable of choosing her next step for herself.

Blob ends with Vi’s tentative rebirth. Her journey with Bob was never about love in the traditional sense—it was about externalizing her deepest fears and desires in a form she could control, then learning, painfully, that even love built from care and creation can grow beyond you.

Bob’s departure leaves Vi with nothing but herself, and that, finally, is enough.

Characters

Vi

Vi, the protagonist of Blob by Maggie Su, is a young woman teetering between post-adolescent drift and adult formation, her life shaped by emotional fragility, disillusionment, and an aching desire for meaning. A college dropout with a dead-end job at a budget hotel, Vi navigates a daily existence that feels suspended, weighed down by grief over past relationships and a gnawing sense of personal failure.

Her inner world is riddled with contradictions: she seeks connection yet instinctively isolates, feels the sting of being overlooked yet often removes herself from situations with her trademark “Irish goodbyes. ” Through these disappearances, Vi tests her worth—does anyone care enough to notice her absence?

The arrival of Bob, the gelatinous blob, disrupts her inertia and catalyzes her emotional unraveling and eventual rebirth. Her relationship with Bob begins with wonder and maternal protectiveness but slowly curdles into an unsettling power dynamic as she projects her longings, insecurities, and traumas onto him.

Vi attempts to mold Bob into the idealized partner—loving, affirming, safe—but this artificial relationship exposes her unresolved guilt, especially over past betrayals like her abandonment of her best friend Lottie. As Bob becomes more sentient and autonomous, Vi’s instinct to control and possess him mirrors the very dynamics that wounded her in her own relationships.

Her crisis deepens after Bob’s departure and Rachel’s betrayal, culminating in a symbolic regression into a “blob” herself. Yet from this lowest point, Vi begins a hesitant path to self-reclamation—choosing a new academic path, revisiting the trauma she’s spent years outrunning, and beginning to understand love not as possession, but as vulnerability, agency, and mutual recognition.

Bob

Bob is a gelatinous, otherworldly creature who initially appears as an absurd anomaly in Vi’s world but gradually becomes the most potent symbol in Blob—of transformation, projection, and the elusive nature of love. When Vi first encounters Bob, he is passive and formless, absorbing cereal and affection in equal measure, functioning almost as a blank canvas for her emotional needs.

He is the ultimate object of projection: a creature who does not challenge, contradict, or abandon her. As Vi feeds and nurtures him, he evolves—sprouting limbs, learning words, and mimicking human behaviors until he begins to resemble a man.

This transformation is uncanny and unsettling, both for Vi and the reader. Bob is both the Frankenstein’s monster of emotional dependence and the embodiment of Vi’s suppressed longing for control and love without risk.

His childlike obedience and simplicity mask the fact that he is becoming his own person—or creature—desiring freedom, sex, and agency. Vi’s efforts to contain him, especially her physical restraint of him with bungee cords, mark a tragic turning point.

Bob’s later departure and alignment with Rachel suggest a painful but necessary liberation. He is no longer Vi’s creation or comfort object but something else entirely—perhaps even someone else.

Ultimately, Bob forces Vi to confront her own limitations, not through confrontation but by leaving her behind, echoing the abandonment she has always feared and inadvertently enacted herself. Bob is not just a creature; he is the living metaphor of Vi’s internal world—shifting, formless, desperate to be loved, but destined to become something outside her control.

Rachel

Rachel, Vi’s coworker at the Hillside Inn & Suites, is initially positioned as Vi’s foil—a high-achieving, clean-cut theater kid who thrives in the structured expectations Vi finds suffocating. She represents a model of feminine success and performativity that Vi both envies and distrusts.

Polite but emotionally distant, Rachel seems self-contained, perhaps even cold, her ambition and composure contrasting sharply with Vi’s chaotic emotional landscape. Their interactions brim with unspoken class and personality tensions; Rachel’s effortless efficiency in the workplace underscores Vi’s sense of inadequacy and failure.

Yet Rachel is not simply an antagonist. As the story progresses, she reveals layers of complexity—inviting Vi to a drag show, initiating small acts of kindness, and eventually forming an unexpected bond with Bob.

This bond becomes the site of the novel’s sharpest betrayal: Rachel’s romantic relationship with Bob is not just a personal affront to Vi, but a usurpation of her creation, her emotional sanctuary. Rachel’s aesthetic remolding of Bob—dressing him in Gap clothing, integrating him into her orderly life—feels to Vi like a second erasure, not only of their relationship but of the creature’s origin and essence.

However, Rachel is not villainized; her choices reflect her own desires for connection, even if they come at Vi’s expense. In this light, Rachel becomes a mirror for Vi—a woman trying to make sense of the strange emotional terrain they both inhabit, using control and polish where Vi uses chaos and retreat.

Elliott (Sea Enemy)

Elliott, who performs as Sea Enemy in the local drag scene, is a childhood acquaintance of Rachel’s and a fleeting yet pivotal figure in Vi’s journey. He is vibrant, performative, and emotionally agile, offering Vi a glimpse into a world of self-fashioning and chosen identity that both intrigues and destabilizes her.

As Sea Enemy, Elliott embodies queerness as fluidity and performance, revealing to Vi the power of aesthetic reinvention and emotional presence. Their banter is effortless, suggesting the possibility of platonic intimacy, but Elliott is also attuned to Vi’s evasiveness and capacity for emotional harm.

When Vi asks Elliott to pretend to be her boyfriend at a family event—an act rooted more in escapism than affection—it backfires spectacularly. Elliott’s public rejection of Vi is not just a response to the lie, but a moral stance: he sees Vi’s pain but refuses to be complicit in her self-destructive patterns.

His withdrawal serves as a moment of rupture, a confrontation with the consequences of her behavior. Though he vanishes from the narrative after this conflict, Elliott’s role is crucial—he is both a brief comfort and a necessary boundary, helping catalyze Vi’s eventual reckoning with herself.

Alex

Alex, Vi’s brother, hovers at the edges of the narrative but plays a critical role in shaping Vi’s emotional world. Their relationship is marked by estrangement, rooted in shared trauma and racial identity that Alex appears to have repressed or distanced himself from.

In Vi’s childhood memories, Alex is a figure of contrast—sexually confident, socially adept, and increasingly aligned with dominant white culture. His detachment wounds Vi, deepening her feelings of invisibility and otherness, especially as their mixed-race identity becomes a site of confusion and silence in their family.

However, during a family dinner later in the novel, Alex surprises Vi with a quiet apology—an understated yet meaningful gesture that acknowledges their past tension. This moment of familial grace does not resolve their complicated history, but it offers Vi a glimpse of repair, a reminder that not all estrangement is permanent.

Alex represents the emotional gaps left by assimilation, gender expectations, and unspoken grief—and his arc, though brief, parallels Vi’s own tentative movement toward reconciliation with herself and others.

Luke

Luke, Vi’s ex-boyfriend, is a ghostly presence throughout Blob, less a fully realized character than an emotional imprint etched into Vi’s psyche. He represents both a real relationship and the broader ideal of romantic validation that Vi internalized from her youth.

In memories, Luke is presented as both stable and subtly cruel, embodying a dynamic of control and neglect that Vi found herself dependent on. Her “Irish goodbyes” in social situations were, in part, a test to see if Luke would notice her, care enough to chase after her.

He never did. This absence becomes emblematic of Vi’s core wound—her fear that she is inherently unlovable, too messy to be held.

When she calls him after losing Bob, her desperation is met with cold detachment. His voicemail, once a source of yearning, eventually loses its sting, suggesting Vi’s emotional growth.

Luke serves as a cipher for Vi’s earliest patterns of emotional abandonment, but his diminishing power over her symbolizes the beginning of her liberation.

Lottie

Lottie, Vi’s childhood best friend, never appears in the narrative present but looms large in Vi’s memories and guilt. Their friendship—close, emotionally intense, and possibly tinged with unspoken attraction—crumbles after Vi’s betrayal.

Envious of Lottie’s popularity and desirability, especially in the eyes of their mutual crush Cole, Vi anonymously torments her with cruel notes. The fallout is devastating: Lottie’s family leaves town, and Vi is haunted by the guilt and the image of a dead baby bird left on her porch.

Whether this was a sign of vengeance, forgiveness, or randomness remains ambiguous, but it cements the emotional violence of her betrayal. Lottie represents Vi’s longing for intimacy and her simultaneous fear of being seen too clearly.

Through Lottie, the novel explores the blurry lines between friendship, jealousy, and desire—especially for young girls navigating race, class, and sexuality. Vi’s unresolved guilt over Lottie becomes one of the novel’s most searing emotional throughlines, a psychic wound that Bob’s presence eventually excavates.

Themes

Loneliness and the Invention of Connection

Vi’s profound sense of isolation underpins much of Blob and informs her actions, decisions, and relationships. From her job at the Hillside Inn & Suites to her estrangement from family and former friends, Vi exists in a liminal state—disconnected from a world that continues to move forward without her.

Bob, the gelatinous creature she finds and gradually humanizes, emerges as a fantastical solution to her emotional void. Her immediate instinct to bring Bob home and care for him reveals a craving for unconditional companionship, but it also signals a troubling attempt to construct a relationship she can fully control.

As Bob evolves—emotionally and physically—Vi’s discomfort grows. What began as a source of comfort soon becomes a mirror for her fears of abandonment and loss.

Rather than seeking connection through mutual vulnerability, Vi builds one that is initially one-sided, designed to serve her emotional needs without challenging her. This attempt ultimately fails as Bob gains agency, forcing her to confront the illusion of safety she created.

Loneliness in the novel is not just the absence of others, but the result of Vi’s inability to trust others with her true self. Her tendency to “disappear” from social situations, to perform “Irish goodbyes,” encapsulates a recurring pattern of withdrawal.

The novel portrays loneliness not as an external condition, but an internal maze that Vi must learn to navigate—recognizing that control and companionship are often mutually exclusive, and that real connection can only occur when she stops projecting her needs onto others and starts engaging with the unpredictable, sometimes painful realities of human intimacy.

Shame, Desire, and Self-Perception

Vi’s adolescent discovery of romance novels, sexual pleasure, and racial consciousness is laced with both awakening and humiliation. Her early encounters with desire—hidden, solitary, and suffused with guilt—set the stage for her conflicted relationship with intimacy in adulthood.

The attic becomes a private sanctuary where she first experiences physical pleasure but also learns to associate it with moral wrongness, reinforced by her own confessions to a stuffed animal. This duality—pleasure intertwined with shame—continues into her adult interactions, especially with Bob.

As Bob becomes more humanoid, his sexual curiosity provokes discomfort in Vi, not because of his behavior alone but because it forces her to confront her own repressed and unresolved feelings about sex, desire, and control. The moment he watches pornography and masturbates is more than a developmental milestone for him—it’s a rupture in Vi’s tightly controlled fantasy.

For Vi, the desire to be desired remains knotted with shame, shaped by early racialized rejections and the internalized belief that desirability must be earned, performed, or manufactured. Her attraction to creating a docile partner speaks to this belief—if she controls the circumstances, perhaps she can avoid rejection.

Yet the more human Bob becomes, the more he resists her script. Her discomfort grows because his growing autonomy threatens the fragile image of herself she’s built through his admiration.

Thus, shame in the novel is not only about sexuality but about identity—racial, emotional, and relational—and the painful disconnect between who Vi is, who she wants to be, and how she believes others see her.

The Illusion of Control and the Fear of Autonomy

Control functions as both a coping mechanism and a barrier in Vi’s life. After a history marked by emotional neglect, racial erasure, and romantic rejection, Vi seeks stability through total authorship of her reality.

Bob becomes her greatest project—born from nothing, raised under her gaze, and sculpted into a companion who will never abandon her. But Bob’s transformation into a thinking, feeling, desiring being undermines this fantasy.

He begins to make his own decisions—changing TV channels, asking to go outside, even forming relationships beyond her—and this shift exposes Vi’s discomfort not with Bob himself, but with her loss of control. Her attempt to restrain him with bungee cords reveals the psychological violence embedded in her fear: if she cannot control Bob, then she must accept that she cannot control anyone, not even herself.

Her desire to freeze Bob in a childlike, adoring state is ultimately a rejection of growth—his and hers. As Bob asserts his autonomy, Vi spirals, turning to alcohol, shame, and self-sabotage.

Her breakdown after he escapes and bonds with Rachel isn’t just about betrayal; it’s about the failure of her constructed world. Control in this novel is depicted not as empowerment, but as a prison—one that isolates Vi from others and ultimately from herself.

The fear of autonomy is twofold: she fears granting it to others and fears reclaiming it for herself. Only in choosing to re-enroll in school under her own terms does she begin to reject false control in favor of authentic self-direction.

Transformation and the Search for Self

At its core, Blob is a story about the struggle to transform—not just physically or socially, but psychologically and spiritually. Vi’s life is shaped by a series of attempts to become someone else: a better version of herself that might deserve love, attention, or success.

From her childhood absorption in romance novels to her shifting identities in school and relationships, transformation is often externally oriented. Bob, initially a blank slate, is her most literal attempt at crafting transformation—he becomes what she instructs, desires, and imagines.

But his metamorphosis ultimately challenges Vi’s understanding of what transformation really means. As Bob grows more human, more independent, Vi is forced to reckon with the fact that true transformation cannot be forced upon others or even upon oneself through sheer will or performance.

It must come from a place of honest reckoning with past pain, present flaws, and future possibilities. When Bob becomes Rachel’s project, complete with Gap clothes and affectations, Vi recognizes her own previous manipulations mirrored back at her.

The creature she once molded now bears the marks of another’s influence. In seeing this, she begins to shed her old patterns.

Her choice to study photography—her first act of self-determination—marks a subtle but powerful transformation. Unlike engineering, which was imposed or inherited, photography represents her desire to see and be seen, to capture rather than control.

Through this lens, the novel portrays transformation not as an escape from the self but a return to it—one that requires accepting the contradictions, pain, and hope that come with real growth.

Racial Identity and Emotional Displacement

Vi’s internalized confusion and discomfort around her racial identity form a constant, though quietly simmering, thread throughout the narrative. As a biracial woman—Asian and white—she often finds herself erased or misunderstood.

Her white mother’s well-meaning colorblindness invalidates her lived experiences of racism, while her brother’s distancing from their Asian heritage intensifies her sense of invisibility. In childhood, being called a racial slur by a white crush not only traumatizes her but cements an early understanding that whiteness is the standard and anything outside it is expendable.

This racial displacement bleeds into her emotional life: she struggles to assert her worth, downplays her needs, and often watches rather than participates in the world around her. Vi’s racial identity is not just about cultural belonging; it’s inextricably linked to her capacity for self-love.

Her jealousy of Lottie—blonde, athletic, charitable—illustrates the internalization of white ideals and the belief that her own difference makes her unworthy of affection or admiration. Bob, in this context, initially serves as a fantasy of unconditional love, free from the racial codes that have governed her interactions with others.

But as he humanizes and is absorbed into another white woman’s life, even Bob becomes part of the racial dynamic Vi cannot escape. In reclaiming her narrative through photography and choosing her future independently, Vi begins to acknowledge the complexity of her identity without seeking erasure or external validation.

The novel thus positions racial identity not as a background detail, but as a central axis of Vi’s emotional displacement and eventual reorientation toward self-acceptance.