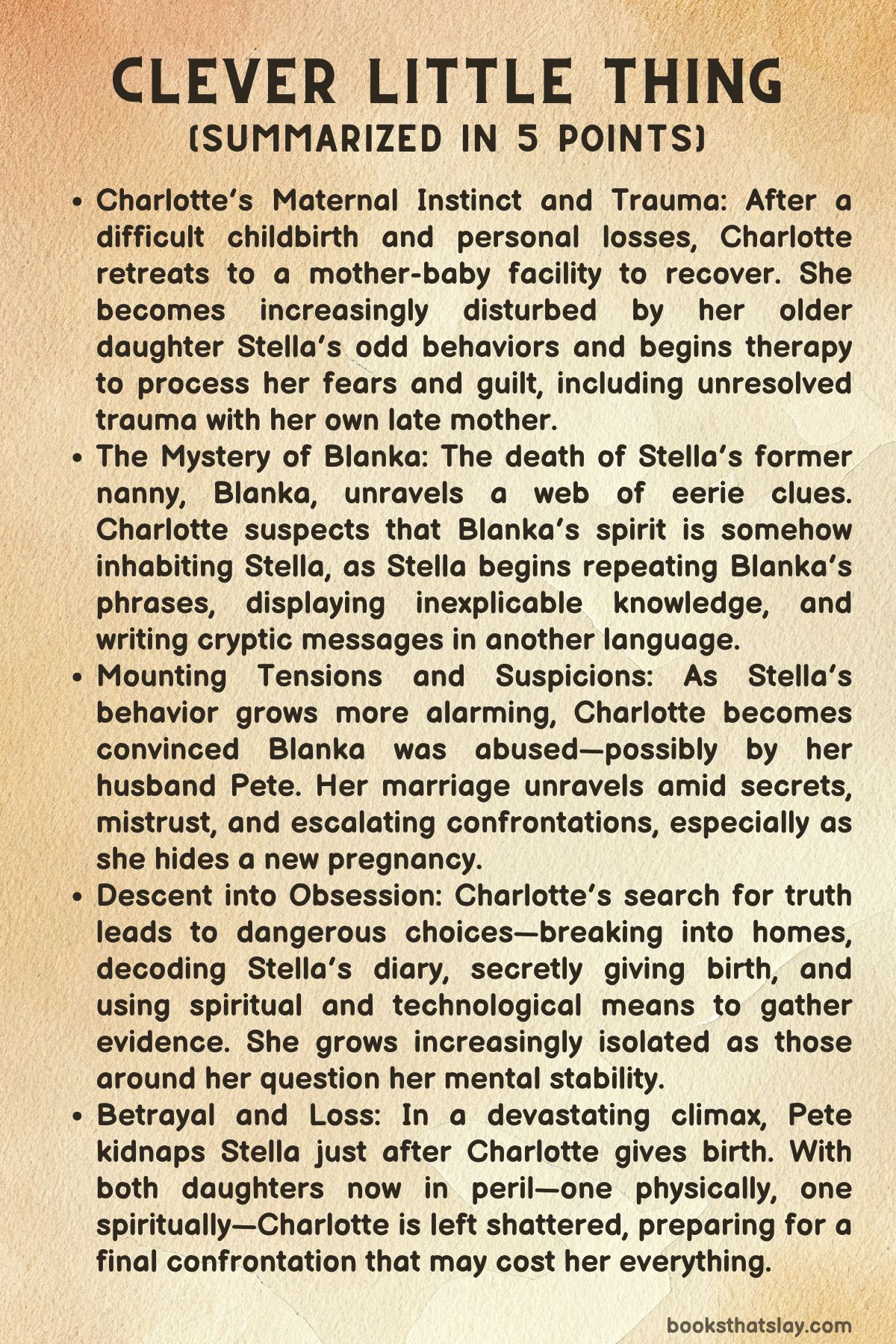

Clever Little Thing Summary, Characters and Themes

Clever Little Thing by Helena Echlin is a haunting and psychologically intense novel that examines the porous boundaries between motherhood, trauma, identity, and the supernatural. At the heart of the story is Charlotte, a woman navigating postpartum vulnerability, her daughter’s unexplained transformation, and the lingering impact of a young woman’s mysterious death.

The novel unfurls over dual timelines—past and present—and pushes the reader to question what is real and what is shaped by grief, guilt, and emotional collapse. It challenges traditional narratives around parenting, mental health, and justice, building toward a conclusion that blends emotional catharsis with eerie ambiguity.

Summary

Charlotte is a mother overwhelmed by anxiety, grief, and a growing sense of powerlessness. The narrative alternates between her present-day stay at a high-end psychiatric facility and the recent past, where her world began to destabilize after the death of her former babysitter, Blanka.

Charlotte has agreed to spend two nights at the mental health center, largely under pressure from her husband Pete. The institution’s routines—taking her shoelaces, denying sharp objects—symbolize the broader disempowerment she feels in her life.

To the outside world, especially to her therapist Dr. Beaufort, Charlotte is a rational woman seeking clarity.

But internally, she fears that her daughter Stella is no longer herself—that something else, perhaps Blanka’s spirit, has taken her place.

The seeds of this belief are planted in the “Then” timeline. Following a beach outing where Stella shows signs of sensory distress and social withdrawal, Charlotte is shaken by the news of Blanka’s death.

Blanka had quit abruptly without explanation, and Charlotte had judged her harshly. Now, she feels consumed by guilt.

Her distress deepens when Stella begins to speak and behave in ways reminiscent of Blanka. Small but chilling signs accumulate: Stella’s precise replication of Blanka’s behaviors, her drawing of a mysterious cross on the wall, and her emotional distance.

Charlotte is haunted by the idea that Blanka is not gone but somehow inhabiting her daughter.

In her effort to understand Blanka’s final days, Charlotte visits Blanka’s mother, Irina. Though initially cold, Irina gradually allows Charlotte into her world of grief.

She explains that Blanka died from an undiagnosed heart condition, drowning in a hot tub. But for Charlotte, the explanation fails to quiet her sense of something supernatural at play.

Back at home, Charlotte’s relationship with Pete grows increasingly strained. Stella continues to exhibit hypersensitivity, a fascination with birds, and emotional volatility.

Pete wants a medical diagnosis, perhaps a label, but Charlotte believes her daughter’s inner world is too sacred to be pathologized. She sees herself as Stella’s protector, determined to offer the compassion she never received from her own distant and rage-prone mother, Edith.

The pressure of navigating Stella’s needs, marital discord, and growing fears leads Charlotte to lash out during an encounter with Cherie, a friend whose autistic son shares similarities with Stella. After a heated confrontation, Charlotte pushes Cherie down.

The incident underscores her unraveling. Even as Stella begins to show signs of more conventional behavior—bathing herself, socializing—Charlotte feels disoriented.

This compliance seems off, not like growth but as though something essential has been erased. During therapy sessions, Charlotte reflects on her cancer history, childhood trauma, and the haunting sense that Blanka’s presence lingers in her home and in her child.

This suspicion becomes an obsession. She begins to notice strange symbols, unfamiliar writing in Stella’s diary, and changes in Stella’s scent.

Charlotte fires Irina, blaming her for enabling this shift, but nothing improves. In desperation, she stages a nighttime ritual by a duck pond, apologizing to Blanka in hopes of freeing Stella.

Stella briefly disappears afterward, deepening Charlotte’s belief that she is losing her daughter permanently. When she returns, unharmed, the sense of dread only escalates.

Charlotte becomes convinced that Stella’s possession is real and that Blanka’s death was no accident.

Charlotte’s mental health continues to spiral, culminating in her escape from the psychiatric facility. She takes refuge with Irina again but discovers a painful truth upon returning home: Pete has been unfaithful, a betrayal that casts their entire relationship in a new light.

What’s more devastating is the growing realization that Pete may have played a darker role in Blanka’s life. Emmy, a friend from Charlotte’s past, confirms Pete’s history of manipulation and possibly worse.

Irina eventually reveals her belief that Blanka was sexually assaulted by Pete, and when Stella—seemingly channeling Blanka—speaks of this trauma, Charlotte begins to accept the horrifying truth.

Charlotte knows what she must do. She confronts Pete during custody mediation, exposing him as Blanka’s abuser and presenting a disturbing recording of Stella—possessed or not—detailing the assault.

The court does not accept it as evidence, but the threat of public scandal and professional ruin forces Pete to relinquish custody. However, he retaliates by attempting to flee the country with Stella.

Charlotte and Irina intercept him at the airport in a climactic confrontation. Stella, speaking Armenian as Blanka might, confirms Charlotte’s claims and forces Pete to surrender.

Back home, Blanka’s spirit finally seems to depart from Stella, who undergoes a visceral change. The household, now consisting of Charlotte, Stella, Luna (the newborn), and Irina, begins to heal.

They relocate to a quiet cottage by the sea, where Stella slowly reclaims her individuality and emotional stability. In an epilogue two months later, the family performs a ritual to scatter Blanka’s ashes.

Charlotte reflects on everything that has happened, considering the possibility that her daughter may have knowingly collaborated in her own haunting as a form of resistance and survival. Whether the possession was real or symbolic, she chooses not to investigate further.

Her focus now is on the life they are building—one marked by hardship, but also by hope and connection.

Characters

Charlotte

Charlotte is the emotional and psychological heart of Clever Little Thing, a woman deeply enmeshed in the disorienting world of motherhood, grief, and unraveling reality. At the novel’s beginning, she is portrayed as fragile but fiercely protective—a mother determined to shield her daughter Stella from forces both visible and invisible.

Her stay at the Cottage, a high-end psychiatric facility, immediately signals her loss of control and her fear of losing touch with herself and her child. What unfolds is a raw, unflinching portrait of a woman riddled with guilt, unresolved trauma, and overwhelming love.

Her guilt over Blanka’s death festers into a near-obsessive quest to understand Stella’s disturbing behavior, which she believes stems from possession. Charlotte’s perception of events is often ambiguous, blurring the lines between supernatural disturbance and psychological delusion.

Her resistance to psychiatric interpretation, particularly by therapists like Dr. Beaufort and Wesley, reveals her deep mistrust of institutional authority and her belief that motherhood grants her a special, unassailable insight into Stella’s inner world.

Throughout the narrative, Charlotte oscillates between insightful lucidity and unstable paranoia. Her eventual confrontation with Pete and the revelation of Blanka’s abuse allow her to emerge as a mother not merely frayed by grief but emboldened by purpose.

By the story’s end, she is not cured but transformed—more aware of her vulnerabilities and more accepting of the limits of her control, yet fiercely resolved to safeguard Stella and Luna from the cycles of harm that once entrapped her.

Stella

Stella is a singular and enigmatic presence in Clever Little Thing, at once an emotionally vulnerable child and a symbolic cipher for her mother’s deepest anxieties. At eight years old, she possesses qualities that set her apart: hypersensitivity, a precocious intellect, and a disarming emotional transparency that borders on the otherworldly.

Her reactions to the world—distaste for certain textures, social withdrawal, and intense fixation on natural phenomena—hint at neurodivergence, yet the novel refuses to pin her down with clinical certainty. Instead, Stella becomes a vessel through which grief, trauma, and supernatural ambiguity are channeled.

After Blanka’s death, her behaviors begin to mimic the deceased babysitter, which unnerves Charlotte and plants the seed of the possession theory. Her eerie calmness, peculiar speech, and sudden shifts in personality make her both a mystery and a catalyst for Charlotte’s descent into emotional turmoil.

As the narrative progresses, Stella’s identity becomes increasingly entangled with Blanka’s unresolved suffering. Yet, there are moments of self-awareness and strategic silence that suggest Stella may be far more conscious of the situation than she lets on.

Her transformation at the end—gradually returning to herself after Blanka’s spirit is released—signals not just healing but resilience. Stella stands as a poignant testament to the impact of adult secrets on children and the incredible, if cryptic, adaptability of the child psyche in the face of trauma.

Blanka

Blanka hovers over the events of Clever Little Thing like a ghost—literally and metaphorically. In life, she was Charlotte’s nanny, a quiet, seemingly meek young woman who was underestimated, misunderstood, and dismissed as insignificant.

In death, she becomes the epicenter of the story’s emotional and psychological weight. Charlotte’s regret over misjudging Blanka intensifies when Stella begins mimicking her behaviors, voice, and even scent, suggesting that Blanka’s spirit has not moved on.

Her tragic backstory slowly unfolds through Charlotte’s interactions with Irina and ultimately culminates in the devastating revelation of her rape by Pete, which likely led to her emotional deterioration and eventual death. Blanka’s “possession” of Stella is a cry for justice, a demand to be seen and acknowledged.

Her presence becomes a form of narrative justice, haunting not merely the characters but the structure of the story itself, which refuses to let her fade into the margins. Even after her spirit is released, her legacy remains, having served as the grim catalyst that forces Charlotte to face the truth about her marriage, her blind spots, and her maternal instincts.

Blanka, therefore, is not only a character but a reckoning—a spirit that demands emotional honesty and accountability.

Pete

Pete is a study in passive aggression and hidden cruelty within Clever Little Thing. On the surface, he performs the role of the concerned husband and rational parent—urging psychiatric care, managing family logistics, and trying to maintain a semblance of normalcy.

But beneath this façade lies a man who is emotionally unavailable, dismissive of his wife’s mental distress, and ultimately complicit in far deeper harm. His infidelity, first hinted at through emotional absence and later confirmed by Charlotte’s observations and Emmy’s confession, sets the stage for his moral collapse.

The revelation that he raped Blanka marks the nadir of his character arc, recontextualizing all prior events and interactions. Pete’s refusal to fully acknowledge his abuse and his cowardly attempt to flee the country with Stella further expose his inability to reckon with guilt or responsibility.

His power lies in manipulation—gaslighting Charlotte, undermining her authority, and hiding behind the veneer of functionality. In contrast to Charlotte’s messy but sincere struggle, Pete is emotionally inert, preferring control over connection.

His ultimate loss of custody and public exposure serve as a form of narrative justice, not only for Blanka but for the generations of women he’s wronged by silence, betrayal, or abuse.

Irina

Irina emerges as one of the most nuanced and unexpectedly redemptive characters in Clever Little Thing. As Blanka’s mother, she begins the narrative steeped in grief and suspicion.

Her initial frostiness toward Charlotte is understandable, driven by the pain of losing her daughter and the murky circumstances surrounding her death. However, Irina’s role evolves from an antagonist to a caregiver, especially when Charlotte finds herself isolated and desperate.

Her folk wisdom, tactile forms of nurturing—such as making nazook or helping Stella with crafts—and quiet strength bring warmth and order to the chaotic world Charlotte inhabits. Irina also embodies the ancestral weight of trauma and survival.

She is the one who reveals the true cause of Blanka’s torment and, by extension, gives Charlotte the language and the courage to confront Pete. Her presence helps bridge the spiritual and emotional gap between Blanka and the living.

Irina ultimately becomes a surrogate maternal figure to Charlotte and a stabilizing force for Stella. In the end, their shared grief becomes a foundation for a new, unconventional family built on mutual respect and healing.

Emmy

Emmy plays a smaller but crucial role in the psychological and emotional tapestry of Clever Little Thing. A former friend of Charlotte’s, she reenters the narrative bearing the dual weight of confession and solidarity.

Her admission of having kissed Pete is both a personal betrayal and a revelatory moment that helps Charlotte understand the full scope of Pete’s duplicity. Yet Emmy’s character is not defined solely by her flaws.

Her willingness to help Charlotte when she’s at her most vulnerable—offering shelter, emotional support, and strategic counsel—marks a turning point in Charlotte’s journey. Emmy becomes the bridge between Charlotte’s alienation and her fight for autonomy.

She represents the imperfect but vital female alliances that punctuate the story, reminding readers that healing often requires confronting uncomfortable truths and relying on those we once cast aside.

Dr. Beaufort

Dr. Beaufort and Wesley represent the institutional side of mental health in Clever Little Thing, each embodying a different facet of psychological interpretation.

Dr. Beaufort, who treats Charlotte at the Cottage, is a well-meaning but ultimately detached figure.

Her clinical demeanor often comes across as condescending or sterile, exacerbating Charlotte’s sense of alienation and reinforcing her fear that no one truly understands the spiritual and emotional depths of her concerns. Wesley, who sees Stella and later Charlotte, is more empathetic but similarly limited by his frameworks.

When he suggests that Charlotte may be projecting her trauma onto Stella, he strikes a nerve that pushes her further into isolation. These characters serve not as villains but as reminders of the limitations of professional detachment when faced with the chaotic, intertwined nature of maternal instinct, trauma, and unresolved grief.

They reinforce Charlotte’s core struggle: to be believed and understood not as a case, but as a mother trying to protect her child from something no diagnosis can explain.

Themes

Maternal Fear and Identity Dissolution

Charlotte’s experience as a mother is not defined by triumph or certainty but by profound, daily fear of failing her daughter, Stella. That fear becomes so consuming that it starts to dismantle Charlotte’s own sense of self.

She cannot discern where her needs end and Stella’s begin, nor can she find a stable point from which to evaluate her choices. This erosion of identity is not just mental or emotional; it is dramatized physically through Charlotte’s institutionalization, the removal of her shoelaces, the constant evaluations by therapists, and her perceived powerlessness in decisions about Stella’s wellbeing.

Charlotte’s inner world is dominated by an anxious vigilance, and her sense of control is repeatedly challenged by her husband Pete, the medical system, school authorities, and even her own memories. The more others question her perceptions of Stella, the more her maternal role becomes a battleground for legitimacy.

This fear isn’t just about losing Stella to mental illness or spiritual possession—it’s about losing the connection that defines Charlotte’s very existence. Her inability to protect Stella from the forces she believes are changing her daughter forces Charlotte to question her own reality, choices, and sanity.

In a society that idealizes maternal intuition and sacrifice, Charlotte’s experience lays bare the immense psychological toll that such expectations can take when they are challenged by complex, ambiguous behaviors in children.

The Ghost of Guilt

Charlotte’s obsession with Blanka’s death is fueled less by mystery than by remorse. Her guilt stems not from a single action but from a history of dismissal, judgment, and superiority she projected onto Blanka.

Once a passive presence in Charlotte’s home, Blanka transforms posthumously into a figure of haunting significance. Charlotte cannot shake the feeling that she failed Blanka, and this guilt becomes inseparable from her worry about Stella’s wellbeing.

The two young women—dead babysitter and living daughter—become psychologically linked in Charlotte’s mind, a connection that grows stronger the more Stella begins to mimic Blanka’s behaviors. These echoes of Blanka in Stella function as more than supernatural cues; they represent the residue of Charlotte’s unacknowledged failures.

She begins to interpret Stella’s changes as punishment, as if Blanka’s spirit is delivering retribution not just for her own death but for the emotional injustices she suffered in life. This ghost is not just literal but metaphorical—it is the haunting presence of Charlotte’s unspoken doubts and suppressed shame.

Charlotte’s journey toward reconciliation involves confronting this guilt head-on, culminating in her ritualistic acts meant to “free” Stella. In doing so, she seeks not only redemption but also a form of penance, hoping that by acknowledging Blanka’s pain, she can release her own.

The Fragility of Mental Health

Charlotte’s descent into paranoia and emotional instability is portrayed with empathy but also with harrowing clarity. Her struggle is not framed as sudden madness but as the slow accumulation of stress, trauma, isolation, and existential fear.

Charlotte has survived cancer, suffered emotional neglect from her own mother, and navigated the everyday complexities of raising a neurodivergent child with minimal external support. These overlapping pressures create a fertile ground for psychological collapse.

Her thoughts, increasingly erratic and conspiratorial, reflect an earnest attempt to find coherence in a world that feels hostile and unknowable. What’s especially tragic is that her suffering is often met with doubt or rational minimization by those around her—Pete, the therapists, school authorities—further exacerbating her instability.

The narrative resists offering a binary between sanity and insanity; instead, it paints a spectrum of mental vulnerability that ebbs and flows with each new stressor. Charlotte’s mind becomes a prism refracting fear into a multitude of distortions: supernatural beliefs, compulsive maternal rituals, and projections of evil.

Her eventual escape from the psychiatric facility is not triumph but a desperate move born of a conviction that nobody else sees the truth. Yet, even in her most unstable moments, Charlotte remains deeply human—her confusion rooted not in irrationality but in the terrifying gray area between trauma and reality.

Supernatural Justice as Feminine Resistance

The theme of possession, rather than operating purely in a horror mode, becomes a powerful metaphor for unacknowledged harm and the female drive toward justice when all other routes are blocked. Blanka’s alleged spirit inhabiting Stella is not framed as evil but as persistent and purposeful—a demand for her story to be heard, her trauma to be recognized.

Blanka’s ghost does not seek vengeance in the traditional sense; she demands truth. Her possession of Stella forces Charlotte to confront the systemic and interpersonal betrayals that led to Blanka’s erasure.

The story links spiritual persistence with social silencing, as Blanka’s voice—channeled through Stella—is the only thing powerful enough to force Pete to reckon with what he’s done. In this way, the supernatural becomes a form of feminist resistance: an insistence that the trauma of women and girls will not remain buried.

Charlotte’s transformation from a mother haunted by guilt to a woman willing to face her husband’s abuse and sever him from their lives illustrates how belief in the supernatural can function as emotional and moral clarity rather than delusion. The rituals and symbols scattered throughout the book—crosses on walls, dead birds, traditional Armenian foods—act as feminist iconography, markers of a different justice system that exists beyond the courtroom: one rooted in memory, embodiment, and maternal protection.

The Shifting Nature of the Child

Stella’s transformation unsettles Charlotte not just because of her behaviors but because it destabilizes the narrative of who Stella is supposed to be. At the heart of Charlotte’s unease is the disorienting reality that children do not remain fixed entities.

They grow, change, recede, and sometimes become unrecognizable. What Charlotte perceives as a haunting or a possession may also be an expression of this natural and painful evolution.

Children absorb their environments; they reflect the tensions around them. Stella’s increasingly uncanny behaviors—her quietness, her crafting of strange dolls, her sudden maturity—may be just as much about Charlotte’s emotional projections as they are about supernatural influence.

The text forces readers to sit in that ambiguity: is Stella changing because she is growing, because she is channeling a ghost, or because she is bearing the weight of her mother’s unresolved trauma? Charlotte fears not only that Stella is no longer herself but also that the “self” she cherished was never permanent to begin with.

The book offers no easy answer to this question, but it insists that the loss of a child’s earlier self is a kind of mourning all parents must navigate. In Charlotte’s case, that mourning is complicated by her guilt, fear, and the overwhelming desire to preserve Stella’s innocence in a world full of unseen threats.

Reclamation Through Female Solidarity

Amid the betrayals Charlotte endures—from Pete, from the psychiatric institution, from other mothers—her path to survival and clarity is illuminated by female solidarity. Irina, initially a source of discomfort and tension, becomes Charlotte’s anchor, her quiet strength rooted in grief and endurance.

Their bond, forged through shared motherhood and pain, provides a space where Charlotte can be vulnerable without fear of judgment. Likewise, Emmy’s confession about kissing Pete, rather than serving solely as another blow, becomes an opening for a different kind of honesty between women—one that acknowledges mutual suffering and the possibility of restitution.

These relationships help Charlotte not only escape physical danger but also reorient her emotional compass. It is through these women that Charlotte finds the courage to confront Pete, to protect her daughters, and ultimately to start over.

Their collective resistance to erasure, their mutual care, and their spiritual ritual of scattering Blanka’s ashes form a quiet but potent chorus against the patriarchy that failed Blanka and tried to gaslight Charlotte. In the end, this solidarity is not framed as heroic or grand but as deeply necessary: a reminder that survival, for women like Charlotte and Irina, comes not through institutions or romantic partners, but through chosen family, mutual recognition, and collective healing.