Just Like That Summary, Characters and Themes

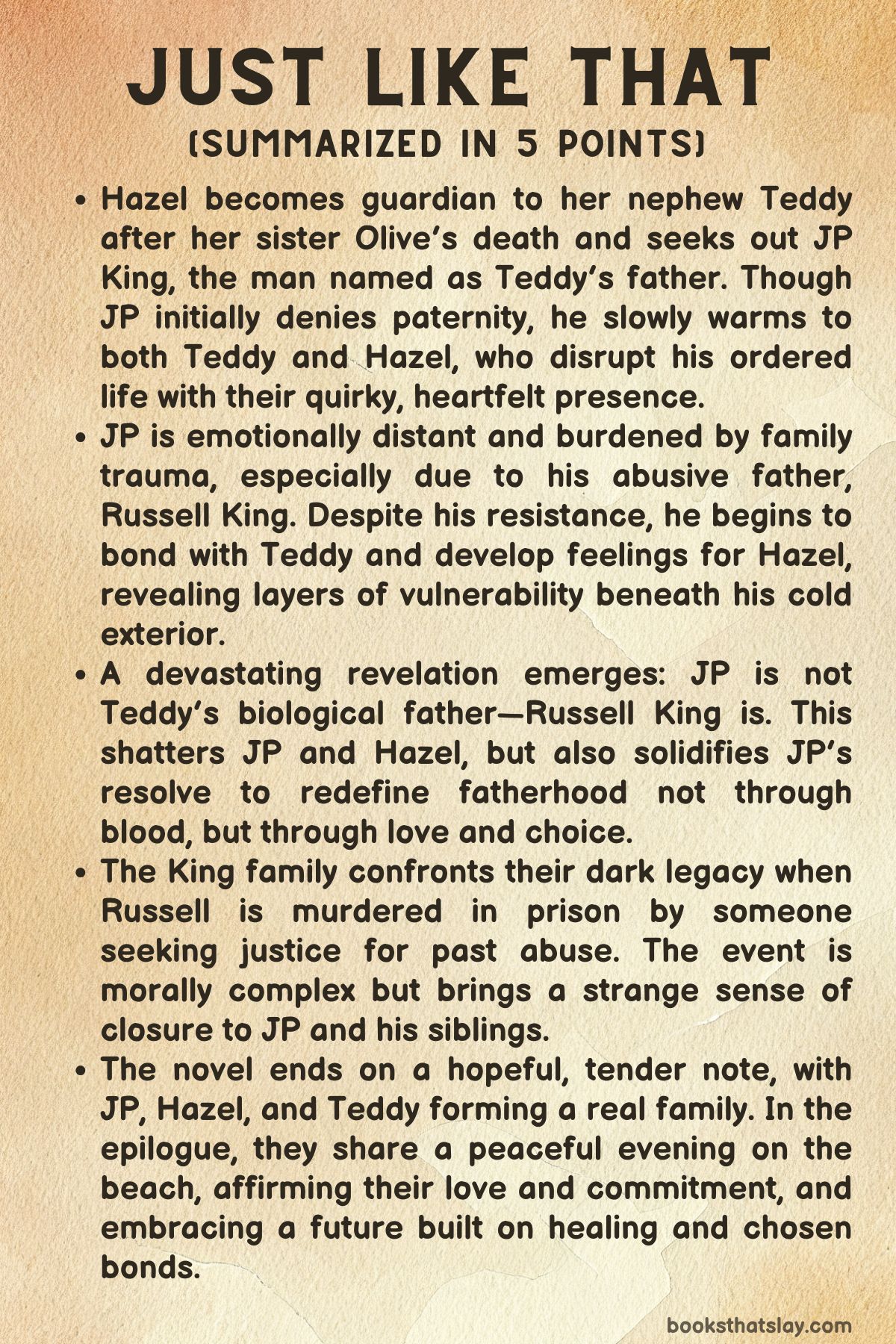

Just Like That by Lena Hendrix is a contemporary romance centered on unexpected parenthood, buried family secrets, and the slow unraveling of emotional walls. It follows Hazel, a free-spirited woman suddenly tasked with raising her nephew after her sister’s death, and JP King, a powerful businessman haunted by scandal and grief.

Their worlds collide when a child’s identity forces them to confront past mistakes, long-held assumptions, and the potential for a different future. Against the backdrop of small-town warmth and big revelations, Just Like That explores what it truly means to be a family—not through biology or obligation, but through choice, trust, and love.

Summary

Hazel’s life is upended when her sister Olive dies unexpectedly, leaving behind a seven-year-old son, Teddy, and naming Hazel as his guardian. Although Hazel is unprepared for motherhood, she’s committed to honoring Olive’s final wish.

When Teddy goes missing in the bustling small town of Outtatowner, Michigan, Hazel is thrust into panic. She finds an ally in Sylvie, a local woman who quickly rallies the townspeople to help.

Teddy is eventually found safe and sound at the local fire station, but the incident sets the stage for something even more jarring: Teddy claims one of the firefighters should call JP King—his father.

Hazel is blindsided. She had no idea that Olive had named someone other than her as a guardian or that there was any father in the picture at all.

When JP arrives, it’s clear he’s a man with his own troubles. A high-powered businessman, he’s reeling from the recent scandal surrounding his father, Russell King, who has been accused of murdering JP’s mother decades ago.

JP approaches the situation with suspicion and coldness, assuming Hazel is after money or notoriety.

Hazel, however, brings documentation proving JP is listed as a guardian and a letter from Olive explaining his role in Teddy’s life. While JP agrees to a paternity test, his demeanor remains harsh and defensive.

Even so, he offers Hazel a place to park her converted skoolie near his home—a gesture that hints at conflicted empathy beneath his distant facade.

As Hazel and JP begin to share space, their interactions grow more complex. JP starts recognizing mannerisms and features in Teddy that resemble his own, leading him to recall a forgotten summer in Chicago.

It was a time of youthful recklessness that may have overlapped with Olive’s pregnancy. The more time he spends around Teddy and Hazel, the harder it becomes to maintain his emotional distance.

Teddy charms JP in unexpected ways, and Hazel, though guarded, proves to be compassionate, grounded, and resilient.

Simultaneously, Hazel wrestles with grief and guilt over her estranged relationship with Olive. Raising Teddy becomes a form of redemption, a way to reconnect with her sister’s memory and find new meaning in her own life.

Hazel and JP continue clashing in court over guardianship issues, but as they do, they begin to recognize mirrored pain in one another. Hazel reveals she carries a genetic predisposition to ovarian cancer, a fact that complicates her choices about motherhood and permanence.

JP, for his part, is weighed down by guilt over his mother’s death and the scandal surrounding his father.

Their relationship reaches a turning point after a particularly emotional day in court when Hazel breaks down by the lake and JP follows her. They share a conversation steeped in vulnerability and mutual understanding.

What begins as empathy transforms into desire, culminating in a passionate kiss. Though both are rattled by the connection, neither can deny it.

At a family barbecue, JP starts to bridge the distance between himself and the community. Despite lingering discomfort and strained family relationships, he shows up—offering a pie and quiet presence.

Hazel leads a moving candlelit prayer in memory of JP’s mother, interlaced with humor and honesty, which fosters a sense of kinship among the group. Hazel begins to see a different side of JP—one that is conflicted, yes, but also deeply human and capable of tenderness.

Soon after, JP makes a bold declaration in front of the judge and his family: Hazel and Teddy will move in with him. Though the decision is rash and surprises everyone, Hazel agrees.

In the intimate space of JP’s beach house, their emotional bond deepens. Their nights become filled with starlight conversations, whiskey, and shared silence.

Hazel’s openness begins to dismantle JP’s walls, and JP, in turn, offers Hazel a sense of stability she hasn’t felt in years. Still, looming over their connection is the unresolved paternity test and JP’s increasingly volatile professional life, as a major client walks away due to his father’s looming criminal trial.

Hazel and JP’s relationship takes on greater intimacy when they spend a night together in the skoolie, physically expressing the passion that has simmered between them. Yet Hazel is haunted by the implications.

In the aftermath, she hands JP a letter Olive had written, revealing that she’d tried to contact him during her pregnancy but had been ignored. What’s more disturbing is the photo that accompanies it—one showing a younger, intoxicated JP beside Olive.

When JP realizes he can’t remember the encounter, he’s horrified to learn that his father had likely intervened behind the scenes.

Seeking the truth, JP confronts Russell in prison. Cold and unrepentant, Russell admits to manipulating Olive—offering her hush money and casting her aside.

Olive had never been after financial gain, but was silenced and shamed. Devastated, JP begins unraveling the toxic legacy of his family.

Financial documents reveal that Olive had been paid yearly, and inexplicably, was listed as the sole beneficiary of an account—a final insult and a symbol of Russell’s control.

Determined to make things right, JP decides to dismantle King Equities, destroying the empire built on lies. Hazel, meanwhile, grows closer to JP’s extended family, especially Veda, who encourages her to follow her heart.

After a thrift store double date, where JP unexpectedly steps in and steals the show, Hazel and JP share a heated argument that breaks into a powerful reconciliation. Their chemistry can no longer be denied, and they finally embrace both emotionally and physically.

Then comes the biggest twist—JP isn’t Teddy’s father. He’s his half-brother.

The revelation is devastating, especially to Hazel, who had been building a future based on a false assumption. Seeking closure, she gathers with her supportive female circle for a séance, hoping to connect with Olive.

What she finds is a letter that reframes everything: Olive’s lie was an act of protection. She feared what Russell might do if he knew about Teddy and trusted JP to offer a better future.

JP, crushed but resolute, visits his father’s grave and later makes the choice to fully distance himself from the family business. He and Hazel are paralyzed over how to break the truth to Teddy.

But Teddy, wise beyond his years, tells JP he still wants him to be his father. At the cemetery, JP offers to bury Olive’s ashes beside his mother’s—a symbolic gesture of healing and unity.

In the epilogue, Hazel, JP, and Teddy have formed a new, chosen family. Hazel is no longer lost, JP has embraced a life of meaning, and Teddy is thriving.

JP proposes to Hazel beside the lake where they first found solace in one another, marking the beginning of a life built on love, resilience, and trust.

Just Like That is a story about the families we build, the pain we overcome, and the love that takes root when we least expect it.

Characters

Hazel Adams

Hazel is the emotional core of Just Like That, a character defined by her restless spirit, creative independence, and fierce loyalty. When she’s thrust into guardianship of her nephew Teddy after her sister Olive’s death, Hazel’s evolution begins.

Initially overwhelmed, she’s a woman running from her past—estranged from her sister, burdened by guilt, and searching for a sense of purpose. Her lifestyle, epitomized by her renovated skoolie, reflects her untethered approach to life, but also her resourcefulness and desire to live authentically.

Hazel’s first encounters with JP King reveal her capacity for confrontation, empathy, and stubborn hope. She sees past his cold exterior and is relentless in her mission to honor Olive’s wishes.

Despite her wariness, she’s emotionally open in moments that matter—crying by the lake, initiating intimacy, or standing firm in court. As the story progresses, Hazel’s growth is evident: she moves from reactive grief to proactive strength, forming a maternal bond with Teddy and emotional intimacy with JP.

Her choices, whether spiritual (the séance) or symbolic (burying Olive’s ashes beside JP’s mother), reveal a woman embracing both love and loss. By the end, Hazel is no longer drifting—she is rooted in purpose, family, and love, transformed by both the boy she’s raising and the man she’s come to trust.

JP King

JP King begins as a man shaped by stoicism, wealth, and unresolved trauma. The shadow of his father’s crimes and the burden of running King Equities have built a wall around his emotional life.

JP is skeptical, dismissive, and deeply cynical when he first meets Hazel and Teddy, believing himself to be under attack by yet another opportunist. However, his icy detachment slowly thaws in Hazel’s presence.

Her skoolie, her honesty, and her unyielding devotion to Teddy chip away at his defenses. When confronted with the possibility of fatherhood and the memory of a lost summer with Olive, JP finds himself unraveling emotionally.

His arc is defined by the painful excavation of memory and identity—realizing that he may have abandoned a child unknowingly and, worse, that his father manipulated Olive and suppressed the truth. JP’s confrontation with Russell in prison is a pivotal moment, marking his break from generational toxicity.

His decision to dismantle King Equities and align his values with integrity and love is monumental. In Hazel and Teddy, JP finds not only healing but clarity.

By choosing to step away from the empire and step into a chosen family, JP becomes a man of vulnerability and courage. His proposal to Hazel at the lake isn’t just romantic; it’s symbolic of his complete transformation—from a man burdened by legacy to one liberated by love.

Teddy Adams

Teddy is the emotional fulcrum of Just Like That. At just seven years old, he is the source of light and emotional clarity for both Hazel and JP.

Introduced in the chaos of being temporarily lost in a new town, Teddy quickly establishes himself as precocious, brave, and emotionally intuitive. He sees JP and immediately latches on, confidently calling him “dad” long before any test confirms—or disproves—that link.

Teddy’s innocent certainty drives much of the adult decisions around him, and his emotional intelligence makes him more than a passive child in the narrative. He humanizes JP, bringing out the softness and protectiveness in a man otherwise driven by detachment.

With Hazel, he becomes both her connection to Olive and her second chance at family. When the paternity results reveal that JP is not his father but rather his uncle, Teddy’s response is poignant and pure: he still chooses JP.

His decision to view JP as his father, regardless of biology, becomes the emotional resolution of the story. In this, Teddy is not only a child who needs love and protection—he’s also a quiet agent of healing and redefinition for both adults.

His stability at the end signifies that love, not blood, is what ultimately shapes family.

Olive Adams

Though deceased at the start of the story, Olive’s presence in Just Like That looms large. She is the catalyst for everything: Hazel’s journey, JP’s reckoning, and Teddy’s placement.

Through letters, memories, and the séance, Olive’s motivations are slowly revealed to be deeply protective and heartbreakingly misunderstood. Her one-night encounter with JP, her decision to raise Teddy alone, and her continued attempts to contact JP—thwarted by Russell’s manipulation—paint her as a woman both strong and vulnerable.

Olive is a victim of a powerful family’s cold indifference, but also a mother who made hard choices to shield her son. Her decision to name JP as guardian in her will suggests hope that he could become the man she once believed in, even if briefly.

The letter she leaves behind, along with the séance experience, provides Hazel and JP with the emotional clarity they need. Olive is not a background figure; she is a ghostly presence whose truth reshapes everyone left behind.

Through her, the story explores themes of silence, survival, and the enduring strength of maternal love.

Russell King

Russell King is the antagonist of Just Like That, a man whose manipulations and moral decay cast a long, damaging shadow. He is the patriarch of the King family and emblematic of power corrupted—someone who not only murdered his wife but also orchestrated a scheme to silence Olive and erase her connection to JP.

Russell’s coldness, even when confronted by JP in prison, is chilling. His lack of remorse and the ease with which he dismisses Olive’s suffering underline the depth of his sociopathy.

Russell’s presence in the narrative is less about overt control and more about the damage left in his wake. He shaped JP into someone distrustful and emotionally stunted, distorted Olive’s life, and tried to manipulate Teddy’s future from beyond the grave.

His death in prison, while not a central plot point, serves as a symbolic end to his reign and a liberation for those he hurt. Russell represents the kind of legacy that must be consciously dismantled—and through JP’s decision to destroy King Equities, the story ensures that his influence dies with him.

Veda

Veda is Hazel’s friend and a member of her spiritual community, representing grounded support and wisdom in Just Like That. She serves as an emotional anchor, encouraging Hazel to live courageously and follow her heart.

Veda’s advice is both practical and mystical, blending candle-lit rituals with emotional honesty. At the barbecue and in private conversations, she is the voice that reminds Hazel not to let grief or fear dictate her future.

Veda’s presence adds texture to the theme of chosen family—offering Hazel a place where she belongs and voices that validate her choices. She embodies the idea that healing is both communal and spiritual, and her presence amplifies the story’s embrace of nontraditional support systems and deep female friendship.

Judge Burns

Judge Burns appears briefly but with great influence in the narrative. Presiding over Teddy’s guardianship hearing, Judge Burns is impartial but perceptive.

He doesn’t let JP off easily for his denial of paternity, nor does he allow Hazel’s emotion to override legal scrutiny. What makes him memorable is his insistence on considering Teddy’s voice in the decision.

By allowing the boy to speak and recognizing the emotional truths beneath the legal uncertainties, Judge Burns acts as a catalyst for empathy and truth. His rulings set the stage for the story’s ultimate recognition that family cannot be reduced to bloodlines alone.

He represents a rare balance of law and humanity, serving as a quiet but significant agent of change.

Themes

Family and Belonging Beyond Blood

Hazel’s sudden guardianship of her nephew Teddy after her sister’s death establishes a central inquiry into the nature of family—one that is not restricted to blood but shaped by choice, care, and emotional commitment. Though Hazel begins as an overwhelmed and grieving sister, her determination to honor Olive’s wishes and provide Teddy with stability becomes a vehicle for her own growth.

The presumed paternity of JP initially positions him as a biological anchor for Teddy, but the narrative challenges that assumption when a paternity test reveals he is actually Teddy’s half-brother. Despite this revelation, it is JP’s actions and devotion that ultimately define his role as a father.

Teddy’s ability to accept JP as his chosen father—affirming it with the clarity only a child can muster—cements the theme that love and dedication, not genetics, create family. Hazel and JP both emerge from fractured family legacies: Hazel’s relationship with Olive was strained before her death, while JP has spent decades alienated by a father who represents the worst of power and deception.

Yet through Teddy, they forge a new dynamic that heals and redefines what family means for them. The formation of this nontraditional unit becomes an act of emotional reclamation, as Hazel and JP step outside inherited trauma and choose to build something nurturing and real.

The conclusion reinforces this idea with JP’s proposal and Hazel’s newfound groundedness, proving that kinship formed through love and responsibility can be just as binding—if not more so—than any legal or genetic link.

Grief, Guilt, and Emotional Inheritance

The entire arc of Just like that is threaded with the emotional aftermath of loss and the weight of unresolved guilt. Hazel is confronted not only with the death of her sister but also with her own regret over their estrangement.

Caring for Teddy becomes both penance and a second chance to connect with the memory of Olive, even as she unravels painful truths. JP, too, is haunted—by the coldness of his father, by the shame of his mother’s murder, and later, by his complicity in dismissing Olive’s earlier attempts to contact him.

The story does not offer simple forgiveness but instead portrays grief as layered and evolving. Hazel’s emotional lows—moments where she breaks down by the lake, or silently cries after intimacy—show how mourning manifests not only through tears but through choices, doubts, and inner reckoning.

The séance scene is particularly symbolic, suggesting that grief, especially unresolved, demands acknowledgment in both the rational and spiritual realms. JP’s journey is marked by a confrontation with inherited pain: he must recognize how his father’s legacy shaped his emotional detachment and take action to reject it.

The burning of King Equities is both a literal and metaphorical act of severance—a symbolic cremation of the past. Both Hazel and JP emerge with scars, but their healing is not framed as complete resolution.

Instead, the novel emphasizes emotional inheritance as a burden that can be transformed through conscious acts of love, self-examination, and bravery in the face of sorrow.

Trauma, Secrets, and the Corruption of Power

Russell King’s shadow looms large over the emotional and moral center of the narrative. A man whose public power and wealth masked private abuses, Russell represents the corruption that seeps into the personal lives of those under his control.

His manipulation of Olive—offering her money to remain silent, and later mocking her memory—illustrates the devastating reach of patriarchal authority. JP, as his son, has internalized this legacy, burying parts of his past and building a life of rigid control.

The discovery that Olive was essentially paid off to disappear recontextualizes not only JP’s guilt but the entire premise of paternity. The trauma caused by Russell’s choices extends generationally: Olive’s secrecy, Teddy’s fatherless upbringing, Hazel’s grief, and JP’s emotional isolation all stem from a man who weaponized silence and withheld compassion.

The eventual exposure of Russell’s crimes, and his murder in prison, create a reckoning that is more ethical than legal. Justice, in this narrative, comes not through courts but through personal revelations and acts of dismantling inherited structures of control.

JP’s decision to destroy the family business is the clearest rejection of the power that once defined him. Even Hazel’s leadership in the séance and her choice to speak Olive’s name aloud reflect a reclaiming of narrative and voice.

In exposing secrets and choosing integrity, the characters break cycles of trauma. The book insists that truth, no matter how painful, is the first step toward liberation from the past.

Emotional Vulnerability and the Tension Between Control and Surrender

At its core, the relationship between Hazel and JP is a study in emotional resistance giving way to vulnerability. JP, conditioned by a lifetime of emotional detachment, initially views Hazel and Teddy with suspicion and judgment.

Hazel, in turn, guards herself with sarcasm, independence, and her nomadic lifestyle in the skoolie. Their flirtation is laden with friction, and their eventual intimacy is charged not just by desire but by years of unmet emotional needs.

The novel charts how each character must learn to surrender control—JP letting go of his need to manage every detail of his life and image, and Hazel releasing her fear of deeper connection and failure. Their dynamic thrives in moments of raw honesty: a kiss after a shared heartbreak, a beachside confession over bourbon, a tense yet revealing confrontation.

The oscillation between closeness and retreat mirrors the real struggle of many wounded individuals trying to trust again. Even their sexual encounters are fraught with emotional consequence, forcing them to confront what they’re truly feeling rather than just what they physically want.

The double date scene, where JP disrupts Hazel’s carefully orchestrated night, shows how playfulness and spontaneity can allow walls to come down. Ultimately, vulnerability is not just a theme but a tool for transformation in this story.

It is what allows JP to become a father in spirit, what enables Hazel to forgive herself, and what gives them both the courage to build something neither expected but both deeply need.

Identity, Choice, and Redemption

Throughout the novel, characters are defined not by where they come from, but by the choices they make in the face of hard truths. Hazel, once an aimless free spirit, becomes a mother figure, a leader, and ultimately, a woman who chooses love not out of dependency but from a place of strength.

JP’s evolution is more dramatic: raised in privilege, trained to hide emotion, and tasked with continuing a business founded on corruption, he spends much of the story in quiet crisis. The paternity confusion, the confrontation with Olive’s past, and his father’s cruelty all force him to reevaluate who he is and who he wants to become.

The most significant marker of his redemption is not his love for Hazel but his commitment to Teddy—choosing to be a father not because of blood, but because of love. The proposal by the lake, made to Hazel after layers of pain have been unearthed, symbolizes a decision to step fully into this new identity.

Teddy’s growth is quieter but equally meaningful; his ability to forgive, accept, and affirm JP as his father despite the truth of their connection speaks volumes about the human capacity for grace. In the end, redemption is portrayed as neither automatic nor guaranteed.

It is a series of hard-won decisions, acts of vulnerability, and moments of choosing to love in the face of disappointment. The story insists that identity is not fixed, but forged—sometimes painfully—through what we decide to do when confronted with the truth.