Loose Lips Summary, Characters and Themes | Kemper Donovan

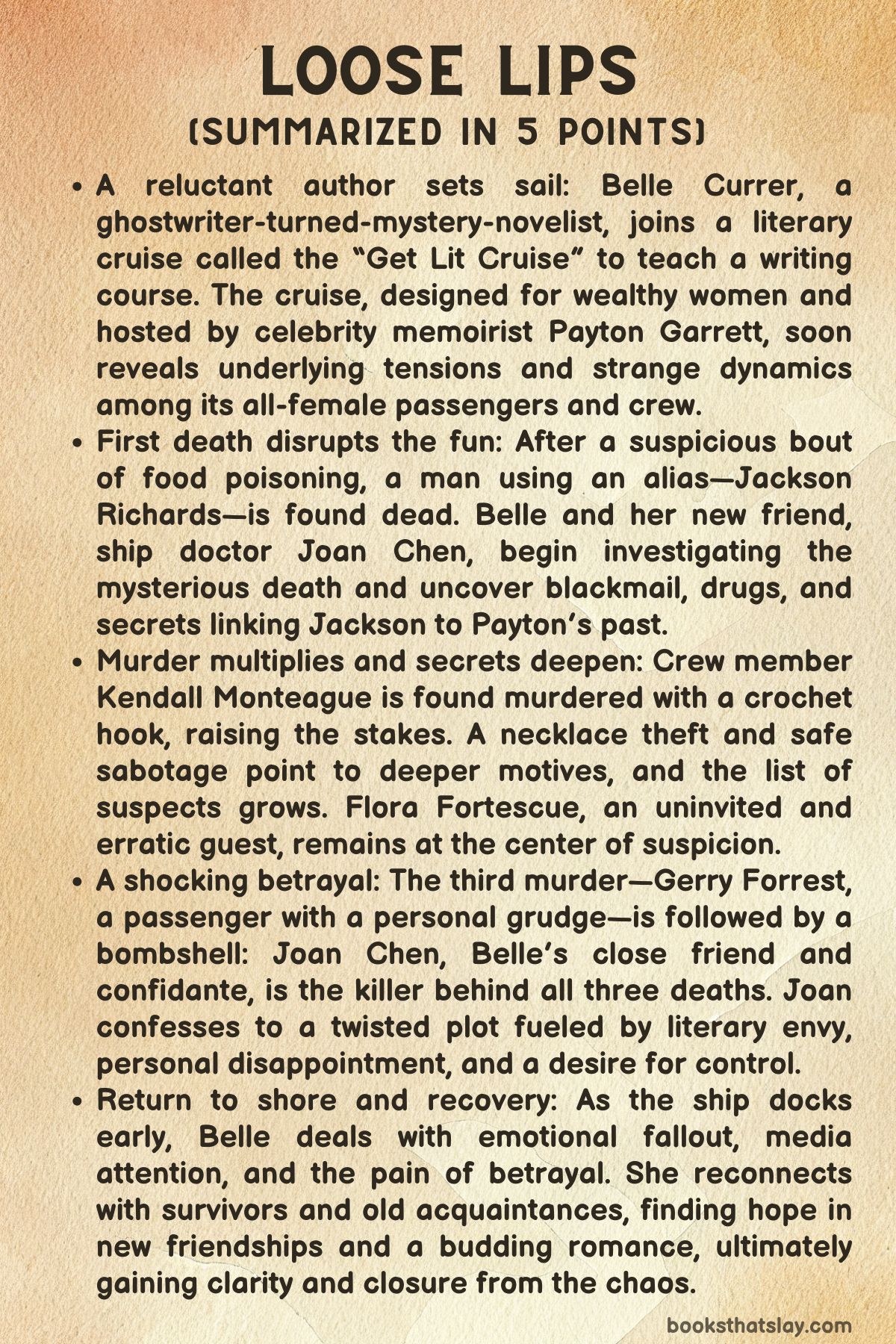

Loose Lips by Kemper Donovan is a mystery novel that unfolds aboard a literary cruise filled with writers, influencers, and secrets. Narrated by Belle Currer, a sardonic ghostwriter and mystery novelist, the novel explores the tensions between art and ambition, truth and manipulation, past wounds and present performances.

What begins as a floating writers’ retreat quickly transforms into a high-stakes puzzle of betrayal, theft, and murder. Belle, both insider and outsider, must navigate clashing egos, professional envy, and personal history as she pieces together the motivations behind a series of increasingly violent events. Loose Lips is a sly, layered narrative about identity, control, and the consequences of silence.

Summary

Belle Currer, a ghostwriter and mystery novelist with a sharp tongue and guarded heart, boards the Merman Rivera for a literary-themed retreat called the Get Lit Cruise. Despite her reservations—especially about cruises—Belle agrees to participate, partly because of her old classmate Payton Garrett, now a memoirist and influencer who is organizing the voyage.

Belle views the cruise with suspicion, recognizing its carefully curated themes of female empowerment and creativity as thin veneers masking deeper rivalries and control.

As the ship departs, Belle reconnects with other figures from her literary past and meets a range of fellow passengers: the charismatic Gerry Forrest, sharp-witted ship doctor Joan Chen, and an unsettling student named Helen Sanchez. Also aboard is Nicole Root, Payton’s wife and a renowned poet whose magnetic stage presence overshadows Belle’s own quiet cynicism.

But the biggest surprise comes when Flora Fortescue—another MFA alum who once accused Payton of plagiarism—makes a dramatic entrance, reigniting old tensions and scandal.

Belle’s seasickness drives her to Joan, and they form a friendship based on shared snark and mystery fandom. Belle also finds herself navigating old feelings when Gideon Pereira, Payton’s ex-husband and Belle’s longtime friend, arrives on board to cover the cruise.

Their flirtation rekindles unresolved emotions. Meanwhile, Belle’s own writing class, though sparsely attended, becomes a site of unexpected connection and inspiration.

Among her students, Helen’s ambition and erratic behavior stand out, creating unease.

The atmosphere shifts when Belle discovers Helen’s manuscript mysteriously placed inside her locked cabin, an act of boundary-crossing that disturbs her. While Belle attempts to maintain professional distance, Helen’s intrusiveness and volatile need for validation grow increasingly uncomfortable.

Belle also grapples with her role in the larger literary ecosystem—both marginal and vital—and the contradictions of being both a ghostwriter and an artist.

Then, during a group dinner, disaster strikes. Jackson Richards, Payton’s flamboyant assistant, collapses and dies from poisoning.

Belle and Joan begin investigating, uncovering that foxglove, a lethal plant, had been hidden in the dinner salad. The intended target may have been Payton, but due to a mix-up caused by Kendall, an overworked waitress, the poisoned plate ended up with Jackson.

Kendall’s rash and panicked confession adds weight to the theory that this was a botched murder attempt.

As suspicion spreads, alliances fracture. Flora, with her history of grievances and gardening expertise, becomes a suspect, especially when it’s revealed she’s using a fake identity on the ship.

Nicole’s crypto necklace is then stolen, complicating the narrative—was the poisoning a cover for theft? Did Jackson know more than he let on?

Payton suspects Flora. Flora insists it was a frame job.

Belle, caught between conflicting stories, begins doubting everyone.

The stakes escalate when Kendall is found murdered, a crochet hook plunged into her eye. This gruesome second death confirms that someone aboard is killing to cover their tracks.

Joan and Belle race to uncover the connections. Belle finally reads Helen’s manuscript and finds it disturbingly brilliant.

Her discomfort grows when she realizes Helen might know more than she’s saying.

The ship turns tense and paranoid. Then Gerry Forrest is found dead, shot in the head.

Flora is discovered holding the gun but pleads innocence. The ship’s atmosphere curdles into full-blown panic.

Payton steps forward, delivering a theatrical public address in the ship’s theater. Her talk morphs into an elaborate reveal, naming Joan as the true killer.

Joan had once been engaged to a man who left her for Jackson. That betrayal shattered her carefully structured future—one shaped by her family’s expectations and abandoned dreams of becoming a writer.

Motivated by vengeance and regret, Joan orchestrated the entire chain of events. She used foxglove to poison Jackson and Payton, hoping to frame Flora.

Kendall became a liability and was killed. Gerry, who possessed knowledge or evidence, was also silenced.

In a final confrontation, Joan confesses to Belle in chilling detail. She explains how she manipulated Kendall, drugged Jackson, staged emergencies to distract the ship’s crew, and repurposed the stolen necklace to deflect suspicion.

She admits she spared Belle because she considered her a kindred spirit. But Belle, quietly recording the confession, ensures Joan will be held accountable.

As Joan is taken into custody, the remaining passengers and staff reel from the trauma. Belle reflects on her journey—not just across the ocean, but inward.

She sees through the performances, the curated personas, and the demands of literary celebrity. Her connection with Gideon remains ambiguous but grounding.

Her once-cynical view of the cruise softens, tempered by hard-earned clarity.

In the end, Belle returns home transformed—not simply by solving a mystery but by confronting the stories people tell, the personas they wear, and the costs of silence. She begins writing again—not ghostwriting, but her own work.

And with that act, she reclaims the authority of her voice, no longer passive or peripheral, but central and clear. Loose Lips concludes not with triumph, but with reckoning—one that leaves Belle not resolved, but awake.

Characters

Belle Currer (Narrator)

Belle Currer, the narrator of Loose Lips, is a complex amalgam of self-deprecating wit, skeptical introspection, and reluctant vulnerability. As a mystery writer who ghostwrites under a pen name, Belle carries a quiet resentment toward the performative literary world she inhabits, especially embodied by figures like Payton Garrett.

Though fiercely intelligent and emotionally perceptive, Belle often hides behind cynicism and sarcasm to manage her insecurities and sense of imposter syndrome. Her arc over the course of the cruise is one of reckoning—with her past, her professional compromises, and her capacity for connection.

Belle is drawn into interpersonal dramas and dangerous entanglements despite herself, and her instincts as a writer serve her not only in storytelling but in navigating social and psychological tension. Her evolving friendship with Joan, her awkward tenderness toward students like Helen, and her complicated attraction to Gideon all illustrate a woman grappling with boundaries, desire, and self-worth.

Ultimately, Belle’s transformation from passive observer to active participant—culminating in her decisive act of recording Joan’s confession—marks her emergence as someone finally willing to confront reality, claim authorship of her life, and tell her own story with unapologetic clarity.

Payton Garrett

Payton Garrett is a force of curated charisma and ruthless ambition. An influencer-author who has parlayed personal trauma into public success, she is a master of performance, branding, and narrative manipulation.

Payton embodies a modern archetype of literary celebrity—one who seamlessly fuses memoir with marketing. Beneath the sleek surface, however, lies a woman deeply afraid of losing control.

Her relationship with Belle is layered with past camaraderie, present rivalry, and mutual contempt masked by professional civility. Payton’s betrayal of Flora—whether intentional or accidental—casts a shadow over her credibility, and her performative TED Talk-style reveal toward the end only underscores her compulsive need to dominate the story.

Yet she also emerges as a character with surprising depth: vulnerable, paranoid, and ultimately shaken by her brush with mortality and reputational ruin. Her marriage to Nicole and her strained interactions with Gideon further expose the fissures beneath her carefully maintained image.

In the end, Payton remains a portrait of ambition warped by the very fame it sought to secure.

Joan Chen

Dr. Joan Chen is the narrative’s most shocking revelation: a charming, acerbic ship’s doctor who evolves from ally to calculating antagonist.

Initially introduced as a witty, like-minded mystery fan and Belle’s intellectual equal, Joan wins the narrator’s trust with her competence, candor, and quiet support. However, beneath her composed exterior lies a volcano of repressed disappointment and thwarted dreams.

Her motivation for murder is not rooted solely in revenge or psychopathy, but in the unbearable tension between the life she once imagined—rooted in creative passion—and the compromises she was forced to make under cultural and familial expectations. Joan’s crimes are both chillingly methodical and tragically human.

Her use of poison, her manipulation of the ship’s hierarchy, and her emotional confession to Belle speak to a desperate need to reclaim authorship over her life narrative. Even in her downfall, Joan remains heartbreakingly articulate—a woman who did not simply snap but made a series of increasingly desperate choices that finally consumed her.

Flora Fortescue

Flora Fortescue is a study in transformation born from rage and betrayal. Once a mousy, overlooked classmate during the MFA days, she reemerges on the cruise as a sharply dressed, venomously poised woman with a vendetta.

Flora’s lawsuit against Payton for alleged plagiarism anchors much of the cruise’s underlying tension, casting her as both wronged artist and unreliable antagonist. Her social reinvention belies a deep-seated bitterness, and her confrontations—particularly with Belle and Kendall—reveal a capacity for cruelty masked by sophistication.

Though she is quick to accuse Payton and fabricate theories to justify her suspicions, Flora is ultimately a red herring in the murder investigation. Her presence, however, is instrumental in illuminating the theme of intellectual theft, emotional gaslighting, and the emotional toll of erasure.

Flora remains a symbol of what happens when artistic passion is ignored, dismissed, or exploited, and her downfall—caught with the gun after Gerry’s murder—embodies the tragic consequences of a life defined by grievance.

Helen Sanchez

Helen Sanchez, the intense and socially awkward student in Belle’s writing workshop, is one of the novel’s most unsettling figures. Eager, ambitious, and emotionally erratic, Helen initially presents as a caricature of the precocious writer desperate for validation.

Yet her talent is real—her manuscript reveals a gifted and disturbing imagination. Helen’s obsession with Belle, including the violation of her private space and the persistent entreaties to read her work, makes her an emotional wildcard.

She represents the dangers of unmet mentorship expectations and blurred boundaries between admiration and entitlement. Helen’s theatricality and neediness challenge Belle’s authority and emotional limits, and her unpredictable behavior adds a simmering layer of menace to the story.

While she is not revealed to be the murderer, her actions force Belle to reflect on the ethical tensions of teaching, rejection, and the responsibilities that come with literary gatekeeping.

Gideon Pereira

Gideon Pereira serves as both romantic interest and moral compass for Belle. A sharp, insightful journalist and Payton’s ex-husband, Gideon is intelligent, flirtatious, and emotionally astute.

His presence on the cruise is tinged with ambiguity—Payton invited him, yet his allegiance gradually shifts toward Belle. Their shared history is full of affection, rivalry, and unfulfilled potential.

Gideon’s ability to see through facades makes him one of the few characters Belle can engage with honestly. He encourages her to write truthfully, challenges her assumptions, and provides warmth in the otherwise emotionally treacherous cruise environment.

Yet he is not without flaws—his past with Payton and his emotional evasiveness at times complicate his reliability. Ultimately, Gideon embodies the possibility of real connection beyond performance, and his presence helps anchor Belle’s emotional evolution.

Nicole Root

Nicole Root, Payton’s glamorous and commanding wife, brings flair and moral ambiguity to the narrative. A poet with a strong stage presence, Nicole is theatrical, bold, and seductive in her power.

Her spoken-word performance, complete with crypto symbolism and moral rhetoric, establishes her as someone who understands both the spectacle and sincerity of storytelling. However, her relationship with Payton is steeped in complexity: supportive yet strategic, affectionate yet performative.

Nicole’s aloofness and confidence often unsettle Belle, and her tendency to weaponize charm makes her hard to pin down. The theft of her necklace and her stylized response to the cruise’s dangers further showcase her flair for drama and mythmaking.

Nicole remains enigmatic—both muse and manipulator, her loyalty seemingly tied to narrative advantage as much as love.

Gerry Forrest

Gerry Forrest, the kindly retiree and aspiring personal essayist, brings a rare emotional softness to the cruise’s otherwise tense atmosphere. His conversations with Belle are marked by quiet wisdom and subtle grief, hinting at a life of unspoken sorrow and loss.

Gerry’s presence offers moments of calm reflection and generational perspective, contrasting the frenetic energy of the younger passengers. His tragic death by gunshot—a shocking escalation in the mystery—transforms him from gentle background figure to heartbreaking casualty.

The discovery of the gun, the accusations, and his untimely end speak to the narrative’s exploration of how innocence is often collateral damage in the crossfire of ambition and vengeance. Gerry’s death underscores the story’s darker thesis: no one, however kind or peripheral, is safe in a world where ego and fear dictate action.

Jessamine LaBouchère

Jessamine LaBouchère, the crocheting romance novelist, is both comic relief and philosophical sage. With her gun cozy and wry wisdom, Jessamine stands outside the main fray yet often provides the clearest moral clarity.

Her conversations with Belle challenge elitist literary hierarchies and celebrate genre fiction as vital and nourishing. Jessamine’s nonchalance and humor offer moments of levity, but her insights are cutting and sincere.

She refuses false intimacy but affirms truth where it matters. Jessamine becomes a mirror through which Belle can assess her own values, particularly around writing, friendship, and self-worth.

In a world of posturing and performance, Jessamine offers a refreshing commitment to authenticity.

Kendall

Kendall, the young and overworked waitress, represents the class tension aboard the Merman Rivera. Her birdlike intensity, physical exhaustion, and accidental role in the salad poisoning elevate her from background character to pivotal figure in the murder plot.

Kendall’s rash, her nervous interactions, and her emotional breakdown under scrutiny highlight the vulnerability of service workers caught in elite games they cannot afford to play. Her murder—brutal and intimate—marks a turning point in the novel’s descent into darkness.

Kendall’s fate underscores the cruelty of manipulation, the invisibility of labor, and the profound cost of being collateral in someone else’s narrative scheme.

Jackson Richards

Jackson Richards, Payton’s flamboyant assistant, is at first a source of comic relief—snarky, loyal, and superficially vain. However, as the story progresses, his character takes on more weight.

His drug use, his knowledge of the safe combination, and his connections to multiple key players hint at a life full of secrets. Jackson’s death by poisoning is both tragic and symbolic: he is a pawn sacrificed in a larger game of revenge.

Though never fully transparent in motive or allegiance, Jackson becomes central to the unraveling mystery, both in life and in death. His character underscores the vulnerability of those who exist on the fringes of power—used, discarded, and ultimately misunderstood.

Themes

Power and Professional Identity

The characters in Loose Lips are frequently caught in a web of self-definition that is inextricable from their professional reputations. For many of the women on the Get Lit Cruise, career success is not just a goal but a performance, constantly managed and publicly curated.

Payton Garrett embodies this most transparently: her empire of memoirs, social media influence, and literary celebrity is founded on the meticulous crafting of a personal brand, one that is fiercely protected even as it comes under scrutiny for alleged plagiarism. Belle, in contrast, approaches authorship with a sardonic detachment, hiding behind a pseudonym and regarding her career with both skepticism and exhaustion.

Their contrasting approaches reflect deeper tensions around what it means to wield power as a woman in a literary landscape that demands both confession and control. Flora, too, represents another angle—someone who has been denied public recognition and consequently channels her bitterness into confrontation.

Power on the ship isn’t just social; it’s also narrative. To control a story—your own or someone else’s—is to exert dominance.

This is made literal in the acts of murder that unfold, where control becomes lethal. Whether through curated public images, stolen intellectual property, or strategic deception, the cruise becomes a battleground for professional identity, with reputations at stake as much as lives.

Friendship, Rivalry, and Female Relationships

Across the spectrum of relationships portrayed, Loose Lips presents a layered and often uncomfortable exploration of how female friendships are shaped by envy, betrayal, loyalty, and survival. Belle’s ambivalent relationship with Payton sets the tone: a mix of grudging respect, buried resentment, and latent affection.

They are bonded by shared history and mutual recognition, yet always at odds over authenticity and ambition. Their dynamic is mirrored in other relationships aboard the cruise.

Flora’s reemergence and her palpable animosity are steeped in the bitterness of past exclusion and perceived theft. Even Belle’s encounter with Flora is charged with guilt and defensiveness, underscoring how friendship can sour into rivalry over time.

The intimacy between Belle and Joan Chen initially appears as a reprieve from this toxicity—a rare female connection rooted in shared interests and emotional intelligence—but it ultimately collapses under the weight of betrayal. Helen Sanchez offers yet another variation: a student whose yearning for mentorship and validation escalates into unsettling dependence.

All of these relationships unfold in a hyper-feminized space designed to encourage community and support, yet the atmosphere is steeped in competition, judgment, and suppressed grievances. The novel refuses to sentimentalize female friendship, instead portraying it as a volatile, high-stakes terrain where affection and antagonism often coexist uneasily.

Class Consciousness and Invisible Labor

Running beneath the glossy façade of a luxury cruise is a sharp awareness of class stratification and the cost of invisibilized labor. Belle’s attention to Kendall, the overstretched server, signals a quiet but meaningful acknowledgment of the exploitative undercurrents sustaining the cruise’s curated glamour.

This empathy is not performative but grounded in memory—Belle once worked in food service and retains a moral clarity about the dignity and importance of such labor. Joan, despite her professional status as a doctor, shares this instinctive solidarity, reinforcing a minor but poignant sisterhood among working women.

In contrast, characters like Flora treat Kendall with disdain, revealing their indifference to service workers’ humanity. The murder of Kendall becomes especially horrifying not just because of its brutality, but because it silences someone already marginalized.

The novel consistently pushes against the privileged blindness of its more glamorous characters, reminding the reader that every luxurious experience is underpinned by unseen labor, often executed under duress. Even Joan’s villainy is rooted, in part, in a narrative of sacrifice—her own dreams foregone for a stable career in medicine, shaped by parental expectation and socioeconomic pressure.

The question of who gets to pursue art, and at what cost, is tied to questions of class as much as talent.

Art, Ownership, and Ethical Creativity

At the heart of the narrative is a complex meditation on the ethics of storytelling—who has the right to tell which stories, and what counts as theft versus influence. The plagiarism allegations between Flora and Payton serve as a flashpoint for this theme.

The novel refuses to offer a clean resolution to the accusation, instead presenting it as a gray zone of literary ethics. Belle, as both ghostwriter and reluctant author, is herself complicit in the erasure of origin, having written for others under anonymity.

Her profession thrives on the invisible transfer of voice, yet she is unsettled by Payton’s success, which seems parasitic. The manuscript Helen forces upon her introduces another ethical dilemma: should mentorship extend to unsolicited manuscripts?

Is refusal an act of protection or dismissal? Even Joan’s crimes are justified, in her mind, as retribution for the creative life she was denied.

Her desire to write is real, and her anger is not entirely unsympathetic, even as her actions are unforgivable. Through these layered depictions, Loose Lips asks the reader to consider how ego, ambition, and injustice shape the creative process—and whether artistic legitimacy can ever be entirely separated from personal ethics.

Isolation, Intimacy, and Perception

Set within the closed system of a cruise ship, the novel magnifies the psychological effects of isolation and forced proximity. The ship becomes a floating stage where every action is watched, every relationship intensified.

Belle’s physical disorientation—her seasickness, her insomnia—mirrors her emotional instability as she navigates shifting allegiances and resurfaces past wounds. Her interactions with Gideon bring moments of warmth and desire, but they are always colored by suspicion, by her fear that even intimacy is a kind of performance.

The boundaries between public and private blur constantly: rooms are invaded, secrets exposed, facades cracked open. Payton’s meticulously composed persona begins to unravel under the pressure of scrutiny, while Belle’s guarded cynicism starts to falter in the face of real emotion.

Even Joan, in her final confession, reveals a terrifying intimacy, disclosing her crimes not as acts of hate but as consequences of unmet longing and stifled self-expression. The cruise isolates its characters physically but exposes them emotionally.

In doing so, Loose Lips explores how self-perception is constantly distorted by others’ gazes, and how connection—romantic, platonic, or antagonistic—is always shaped by the power dynamics embedded in who is looking and who is being seen.