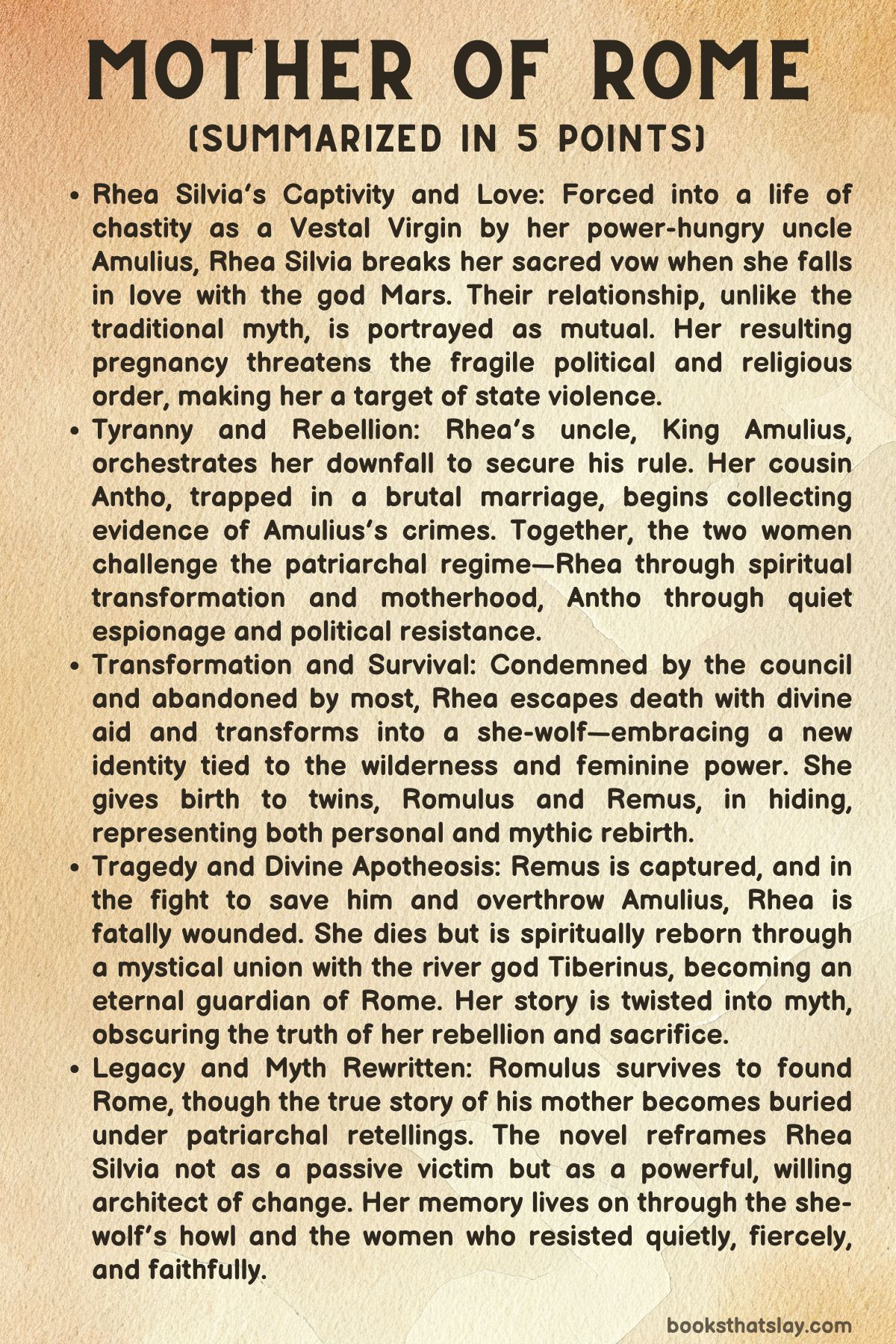

Mother of Rome Summary, Characters and Themes

Mother of Rome by Lauren J. A. Bear is a richly imagined historical fantasy that reinterprets the legend of Rhea Silvia, the mother of Rome’s founders, Romulus and Remus. Instead of relegating her to a mere vessel of myth, the novel elevates Rhea to a complex protagonist—a warrior of grief, a symbol of defiance, and eventually a divine protector.

From her forced initiation as a Vestal Virgin to her divine union with Mars, her exile, transformation, and eventual apotheosis, the story reclaims the maternal heart of empire-building. Through political betrayal, godly interference, and fierce love, Rhea Silvia becomes more than a mother—she becomes the myth itself.

Summary

Rhea Silvia begins as the last living daughter of the Silvian line, a royal family tracing its lineage back to Aeneas of Troy. Her royal blood makes her a threat to her uncle Amulius, who has seized control of Alba Longa.

To neutralize her politically and prevent her from producing heirs, he forces her into the sacred, celibate life of a Vestal Virgin. Stripped of her name, rights, and identity, Rhea is expected to serve Vesta, goddess of the hearth.

But Rhea has already broken the vow of chastity before taking it, having been seduced by the god Mars in the woods during the Latin Festival. This hidden union carries immense symbolic and divine weight, suggesting a destiny beyond the control of mortals.

Before her vow, Rhea had been a vibrant young woman closely bonded with her cousin Antho and deeply devoted to her younger brother Aegestus. The comfort of this intimate world is shattered when Aegestus is brutally killed on a hunting trip.

Lucian, a close family friend and surrogate brother, returns mortally wounded, bearing news of Aegestus’s death. Rhea’s world collapses in grief.

Her father, King Numitor, retreats into opium-fueled numbness, leaving her exposed to Amulius’s manipulation. Blaming the Etruscans, Amulius exploits the tragedy to consolidate power.

He then publicly forces Rhea into the Vestal order in a grotesque display of domination masked as sacred ritual.

Grief turns to rage. Rhea flees into the woods and calls upon Mars for guidance in exacting revenge.

Instead of giving her weapons, Mars teaches her that vengeance requires more than blood—it demands patience and transformation. She returns to the Regia knowing she must bide her time.

But Amulius, driven by an obsessive hatred of her mother and a twisted desire for Rhea herself, visits her chamber in a drunken state and assaults her. She fights back, and from this moment emerges the seed of her resistance—her body may be weaponized, but her spirit remains unbroken.

Antho, meanwhile, nurtures her own rebellion. Trapped under her demonic father Calvus’s rule, she finds solace and strength in her forbidden love for Leandros, a palace guard.

As secrets begin to surface—including that Amulius may have orchestrated Aegestus’s death—Antho becomes an active co-conspirator in Rhea’s quiet plans for justice. Rhea’s pregnancy, the result of her divine union with Mars, progresses in secret.

She is eventually banished to a forest hut as punishment, cut off from all support.

Even in exile, Rhea clings to small mercies. A visit from a river spirit and the symbolic arrival of a starving mother wolf remind her of her own hunger—for companionship, for strength, and for survival.

Her cousin continues to help from afar, sending talismans and supplies to aid her through childbirth. When the time comes, Rhea labors alone, without aid or comfort, giving birth to twin sons.

The birth is raw, visceral, and deeply spiritual—an act of animalistic survival and motherly love.

But this joy is short-lived. Amulius’s soldiers discover her, assault her, and abduct the newborns.

Beaten nearly to death and imprisoned in a dungeon, Rhea offers her life for her sons’ safety. Her body fails, but her spirit ascends.

In a visionary realm, she meets the goddess Cybele. Knowing she will not survive in human form, Rhea pleads for transformation—not for herself, but to protect her children.

Cybele grants her the body of a wolf, stripping her of language and touch, but not love. Rhea accepts.

As a she-wolf, Rhea slaughters the soldiers who wronged her and tracks her sons to the Tiber River. She saves them from drowning and shelters them in a cave.

One of the twins, Viridis, is nearly lifeless until Rhea growls in fierce desperation, prompting him to nurse. This primal act revives him.

Rhea becomes their protector, wrapped around them for warmth and safety. In the process, she surrenders her humanity but becomes something greater—a force of maternal divinity.

Years later, the story crescendos as Alba Longa faces revolt. Romulus and Remus, now grown and awakened to their true parentage, lead a rebellion with the support of the people and former allies of the Silvian line.

The city’s disenfranchised join the cause, rallying behind the twin heirs and their promise to break the cycle of oppression. Rhea, sensing the moment, transforms back into her wolf form one last time and returns to the city.

As the rebellion ignites, Remus narrowly escapes capture and is reunited with Romulus. The twin brothers publicly claim their lineage, invoking their divine origins and maternal legacy.

Their campaign is bolstered by symbolism, including the ash-markings of wolf’s blood—a sign of defiance. Inside the palace, Queen Claudia urges her husband to flee.

Amulius refuses. He and Numitor, once a hollow figure, meet over poisoned wine.

In this silent confrontation, justice is served—not with swords, but with quiet resolve.

Rhea reclaims her human form for one final night and enters the palace. There, she confronts Amulius alongside Antho and her sons.

Her words, her very presence, unmask his lies. Amulius threatens Leandros, Antho’s lover, but Rhea’s defiance destabilizes his grip on power.

She steps forward to kill him, but Numitor reveals the wine was already poisoned. Rhea accepts this final act of justice.

Antho then declares her freedom from her abusive father and claims her secret marriage to Leandros. Their son, Ezio, is named as the true heir to Alba Longa.

Romulus and Remus renounce any royal claim, promising instead to found a new city. Rhea, for the first time, allows herself to rest, surrounded by the people she fought to protect.

As dawn breaks, Rhea dies from her wounds atop the Regia. But she is not gone.

She meets Tiberinus in the afterlife, who offers her immortality. She accepts, becoming the divine Queen of the Tiber.

In the epilogue, her sons entomb her beneath the Palatine Hill. Rome is born, but Rhea’s presence echoes in its foundation—feral, maternal, and undying.

Her howl lingers as both warning and benediction, a legacy of fierce love that reshaped an empire.

Characters

Rhea Silvia

Rhea Silvia is the impassioned heart and transformative force of Mother of Rome. At the novel’s outset, she is a princess brutalized by fate—stripped of her royal identity, her familial anchors, and her bodily autonomy.

Yet beneath the layers of grief and subjugation simmers an indomitable will. Her evolution from daughter of a fallen line to sacred mother-wolf of Rome unfolds across realms—mortal, divine, and mythic.

Her grief, particularly after the murder of her younger brother Aegestus, creates a crucible of pain that forges her inner strength. Betrayed by her uncle Amulius and abandoned by her father Numitor, she is thrust into the role of a Vestal Virgin as a political tool to silence her bloodline.

Her initial helplessness does not last; Rhea transforms sorrow into resolve, channeling her rage through a forbidden liaison with Mars and a clandestine rebellion. Her later exile, pregnancy, and brutal imprisonment become stages of spiritual elevation.

Her metamorphosis into a wolf—granted by Cybele as an act of maternal sacrifice—cements her as both legend and protector. Her final return to human form, brief yet luminous, allows her to witness the legacy she birthed.

Rhea Silvia is not simply a character; she becomes Rome’s archetypal mother—at once divine, savage, and heartbreakingly human.

Amulius

Amulius is the tyrannical usurper whose lust for power drives much of the novel’s conflict. He is more than a mere antagonist; he embodies patriarchal cruelty, political opportunism, and psychological corruption.

His rise to power is characterized by calculated manipulations—staging rituals to validate his rule, forcing Rhea into religious servitude to eliminate succession threats, and exploiting public fear of the Etruscans to consolidate authority. Yet beneath his political maneuvers lies a deeper rot: his obsessive desire for Jocasta, Rhea’s mother, and then Rhea herself, reveals a man ruled by perverse appetites as much as ambition.

His predatory tendencies and violent insecurities expose his moral bankruptcy. He is ultimately undone not by an external enemy but by the consequences of his own corruption—his downfall engineered quietly and poetically through poisoned wine by the brother he betrayed.

Amulius is the face of empire gone sour, of order maintained through terror, and of masculinity weaponized against the sacred feminine.

Antho

Antho offers a delicate but vital counterbalance to Rhea Silvia’s ferocity. She begins the story as a softer, more domesticated character—dreaming of escape, caring for her cousin, and loving quietly.

Yet beneath her gentleness lies a growing awareness and strategic intelligence. She is caught between worlds: daughter of a demonic father, cousin to a revolutionary, and lover to a principled soldier.

Her trajectory is one of incremental awakening. Initially a confidante, she evolves into an agent of resistance—transporting supplies, guarding secrets, and, eventually, asserting her political and personal agency.

Her marriage to Leandros and her son Ezio’s future leadership represent not only hope but the triumph of kindness over coercion. Antho, who once lived in the shadow of others’ power, emerges as a pillar of the new order—strong not through dominance but through devotion, insight, and quiet rebellion.

Numitor

Numitor is the ghostly father-figure whose descent into addiction mirrors the collapse of the old order. Once king, he becomes a figure of detachment and sorrow following the death of his children and the political betrayal by his brother Amulius.

His grief paralyzes him, and opium becomes his means of escape, rendering him passive in the face of tyranny. Yet his final act—poisoning Amulius in a quiet, intimate reckoning—redeems him as a man capable of justice, if not leadership.

His gesture is understated yet monumental, embodying the complexity of a man broken by loss but still anchored to moral truth. In this way, Numitor’s arc is not about redemption through strength but about the subdued courage to do what is right when it matters most.

Mars

Mars, the god of war, appears not as an omnipotent deity but as a haunting and intimate force in Rhea’s life. He is both lover and mentor, the spark that ignites Rhea’s rebellion and the divine thread that elevates her tale from tragedy to legend.

His presence is sensual, mysterious, and emotionally charged. He refuses to fulfill Rhea’s impulsive desire for violent revenge, instead instructing her on the virtues of patience, strategy, and internal fire.

In his rejection of easy solutions, Mars plays the role of a cosmic guide, shaping Rhea’s transformation without seizing control. His divine involvement also situates Rhea within a mythic lineage—his children, Romulus and Remus, will carry forward the divine purpose their union set in motion.

Mars is less a character with a personal arc than a mythic agent who catalyzes Rhea’s metamorphosis from mortal to mother of Rome.

Romulus and Remus

Romulus and Remus, though introduced late in the narrative, symbolize the realized legacy of Rhea Silvia’s sacrifice. They are raised in the wilderness, nourished by their mother in wolf form, and forged by survival.

When they emerge as young men, they become the embodiment of divine justice and renewal. Romulus, the more politically attuned of the two, takes the lead in rallying Alba Longa’s citizens and confronting the rot at the city’s core.

Remus, his return from captivity miraculous, serves as the emotional anchor of the rebellion. Their bond as brothers adds an emotional texture to the rebellion’s fire.

Together, they represent the birth of a new era, rejecting claims to a broken throne in favor of founding a new city—Rome. They do not seek to avenge Rhea through blood alone, but to honor her through creation.

Their journey is as much about memory and meaning as it is about conquest.

Leandros

Leandros, a royal guard and Antho’s lover, is the story’s quiet moral compass. His loyalty, bravery, and compassion stand in contrast to the decay within the palace walls.

Though a soldier, he is more protector than warrior—risking his life to support Rhea and Antho’s rebellion, and ultimately marrying Antho in secret to preserve love against a backdrop of brutality. His role is not grandiose, but essential; he represents the possibility of goodness and justice within a corrupt system.

His calm strength becomes a foundation upon which Antho builds her own transformation, and his child, Ezio, becomes the future that Rhea and Antho sacrifice to preserve.

Ezio

Ezio is the symbolic torchbearer of the next generation. As the child of Antho and Leandros, and the future heir of Alba Longa, he embodies the possibility of a kingdom ruled by integrity and love rather than fear.

Though young, his presence commands significance—he is the answer to the city’s fractured lineage, a child born not of gods or vengeance but of hope and unity. His legitimacy, supported by Rhea and Romulus, suggests a future not defined by the mistakes of the past but guided by the vision of those who dared to defy it.

Tiberinus

Tiberinus, the river god, represents spiritual release, love beyond mortality, and the redemptive power of union. His earlier interactions with Rhea in exile are gentle and restorative, offering her a sliver of peace amid her isolation.

He returns at the novel’s conclusion as a divine figure offering immortality, not as a prize for heroism, but as a final act of grace. Their reunion is not passionate in the mortal sense but tender, transcendent.

By choosing to join him as Queen of the Tiber, Rhea relinquishes her suffering and embraces a divine afterlife rooted in love, rebirth, and mythic memory.

Queen Claudia

Claudia, Amulius’s queen, is a minor but poignant figure whose tragedy lies in her inability to escape the man she married. Her desperate plea for Amulius to flee during the rebellion reflects both fear and insight—she sees the end before others do, yet lacks the agency to alter its course.

She is not complicit in his crimes, but her silence reflects the limits imposed on women in power. Her presence underscores the emotional collateral of tyranny and the futility of alliances forged through control rather than love.

Themes

Maternal Sacrifice as a Sacred Act of Reclamation

Rhea Silvia’s journey in Mother of Rome is defined by her transformation into a maternal figure whose love transcends both mortality and identity. Far from being a passive or domestic concept, motherhood in Rhea’s case becomes an active, revolutionary force that rewrites the terms of power, autonomy, and divine engagement.

From the moment she chooses to carry the children of Mars—against the constraints of her forced Vestal vows—Rhea reclaims the very concept of motherhood from a role used to subjugate her into one that becomes her source of defiance and eventual apotheosis. Her pregnancy is not only a rebellion against Amulius’s political machinations but also a declaration of her bodily autonomy.

Her labor, marked by solitude, pain, and primal resolve, becomes a crucible through which she proves the depth of her endurance and love. The moment she sacrifices her human form to Cybele to ensure her sons’ survival—losing her voice, her touch, her identity—elevates maternal sacrifice to a sacred act.

This transformation is not framed as martyrdom, but as a conscious, empowered choice. Her wolf form, feral yet nurturing, becomes the perfect emblem of this maternal force—capable of killing and protecting with equal ferocity.

Even as her humanity is stripped away, her essence is magnified. She becomes not just the mother of Romulus and Remus, but the mother of a future civilization, her body and spirit inseparably fused into the mythic fabric of Rome.

In this narrative, motherhood is not sentimentalized; it is weaponized. Rhea does not find redemption through sacrifice—she redefines what sacrifice means entirely, turning it into a generative and divine power.

Political Betrayal and the Erosion of Trust

The collapse of familial and civic structures in Mother of Rome is not merely a background for Rhea’s suffering—it is the stage upon which betrayal systematically corrodes every meaningful bond she once held. The initial blow comes with the murder of her brother Aegestus, an act orchestrated under the guise of foreign threat but later revealed to be a calculated move by Amulius.

His betrayal is not simply personal—it is generational and systemic. By usurping Numitor’s throne and dismantling the Silvian legacy, Amulius rewrites history to serve his ambitions, severing Rhea from both her political birthright and her familial anchor.

Her father, too, betrays her in a more passive but equally devastating manner, retreating into opium and grief, abandoning his daughter to suffer alone. Even the institutions meant to provide sanctuary and honor, such as the Vestal order, become tools of suppression, used to politically neutralize her under the guise of religious purity.

These layers of betrayal destabilize Rhea’s understanding of loyalty, safety, and truth. Her resulting paranoia and rage are not irrational—they are grounded in the constant, lived reality that trust has become a liability.

The few relationships she clings to—Antho, Mars, Leandros—stand in sharp relief, made all the more significant by their contrast with the systemic treachery surrounding her. Through this, the book explores how betrayal, when institutionalized, becomes indistinguishable from governance.

It suggests that in a world where power is built on lies, truth becomes a form of resistance, and surviving betrayal requires not forgiveness, but reinvention.

Bodily Autonomy and Resistance to Patriarchal Control

Rhea’s body is a battleground long before it becomes the vessel of divine maternity. In Mother of Rome, the control over women’s bodies—by religion, politics, and patriarchal figures—is depicted as both a symbol and instrument of domination.

Rhea’s forced induction into the Vestal order strips her of reproductive agency, rendering her symbolically inert to ensure she cannot produce heirs that threaten Amulius’s rule. This act is portrayed not as sacred, but strategic, exploiting divine tradition to cement male power.

Yet Rhea’s resistance begins in her body: in choosing to engage with Mars and conceive children, she asserts a right to her own desire and destiny. Her defiance is not abstract; it is rooted in physical choices and consequences.

Later, as her pregnancy becomes more visible and burdensome, the pain and discomfort underscore her isolation, but also her resolve. The beatings she suffers and the attempted assault by Amulius are further attempts to reassert control over her body through violence.

Each time, Rhea reclaims control through resistance—biting, surviving, strategizing. Her ultimate transformation into a wolf, which involves the literal abandonment of her human form, is paradoxically her most powerful act of bodily autonomy.

She chooses the terms of her transformation, embracing a form that allows her to protect her children while escaping the systems that once controlled her. In this way, the body is neither a prison nor a vessel—it is a terrain of revolution.

The narrative asserts that true autonomy does not come from institutional freedom, but from the fierce determination to define one’s body on one’s own terms, even at the cost of humanity.

Legacy, Memory, and the Construction of Myth

In Mother of Rome, legacy is not a passive inheritance but an act of creation, memory, and defiance. Rhea Silvia begins her story clinging to the memory of her lost family—her mother, her brothers, and the crumbling remnants of the Silvian line.

Yet she refuses to let their memory fade into nostalgia or tragedy. Each act she undertakes is meant to honor, avenge, or preserve what they represented.

The wooden figures she carves while pregnant are not just distractions—they are totems of remembrance and seeds of storytelling, small acts that reinforce continuity between past and future. Similarly, her determination to protect her children is not only maternal—it is historical.

She sees in them the potential to resurrect a future that was stolen from her family, to rewrite the story Amulius tried to erase. By the time her sons rise against Alba Longa, Rhea’s myth has already begun to take shape—not because others wrote it, but because she lived it deliberately, sculpting her suffering and survival into a legacy meant to outlast her body.

Her final return to the Regia and her transformation into a goddess of the Tiber formalize what has already happened in practice: her elevation from disgraced woman to foundational legend. Even in death, her memory is secured through burial beneath the Palatine Hill, anchoring her body in the land that will become Rome.

This theme suggests that legacy is not guaranteed by bloodline or power—it must be forged through sacrifice, storytelling, and acts that demand remembrance. Rhea does not inherit a myth—she becomes one, on her own terms.

Divine Indifference and Human Transcendence

While gods are present throughout Mother of Rome, their role is far from benevolent or all-knowing. Mars, Tiberinus, and Cybele all interact with Rhea, but none of them intervene to prevent suffering or provide clear salvation.

Instead, divinity in this narrative is characterized by detachment, riddles, and conditions. Mars refuses to make Rhea an assassin, offering wisdom instead of weapons.

Cybele grants Rhea’s wish only at the cost of identity and embodiment. Tiberinus offers immortality, but only after a lifetime of pain and silence.

These interactions emphasize that the divine does not rescue—it challenges. Rhea’s journey becomes a series of negotiations with higher powers who offer tools but not answers.

Her resilience, therefore, is not a gift of the gods but a triumph of will. She outlasts divine indifference by embracing her own agency, making choices that prioritize her values over divine agendas.

In doing so, she transcends the gods themselves, not by defying them, but by absorbing their lessons and moving beyond their limitations. Her final transformation into a river goddess is not framed as reward, but as recognition.

The divine grants her elevation because she has already earned it—through blood, suffering, and fierce love. This theme reframes the relationship between mortals and gods, suggesting that human endurance, sacrifice, and love can be more powerful than divine command.

Rhea becomes a symbol of this truth: a mortal who rose not through favor but through fire, reshaping destiny by sheer force of spirit.