Old Soul by Susan Barker Summary, Characters and Themes

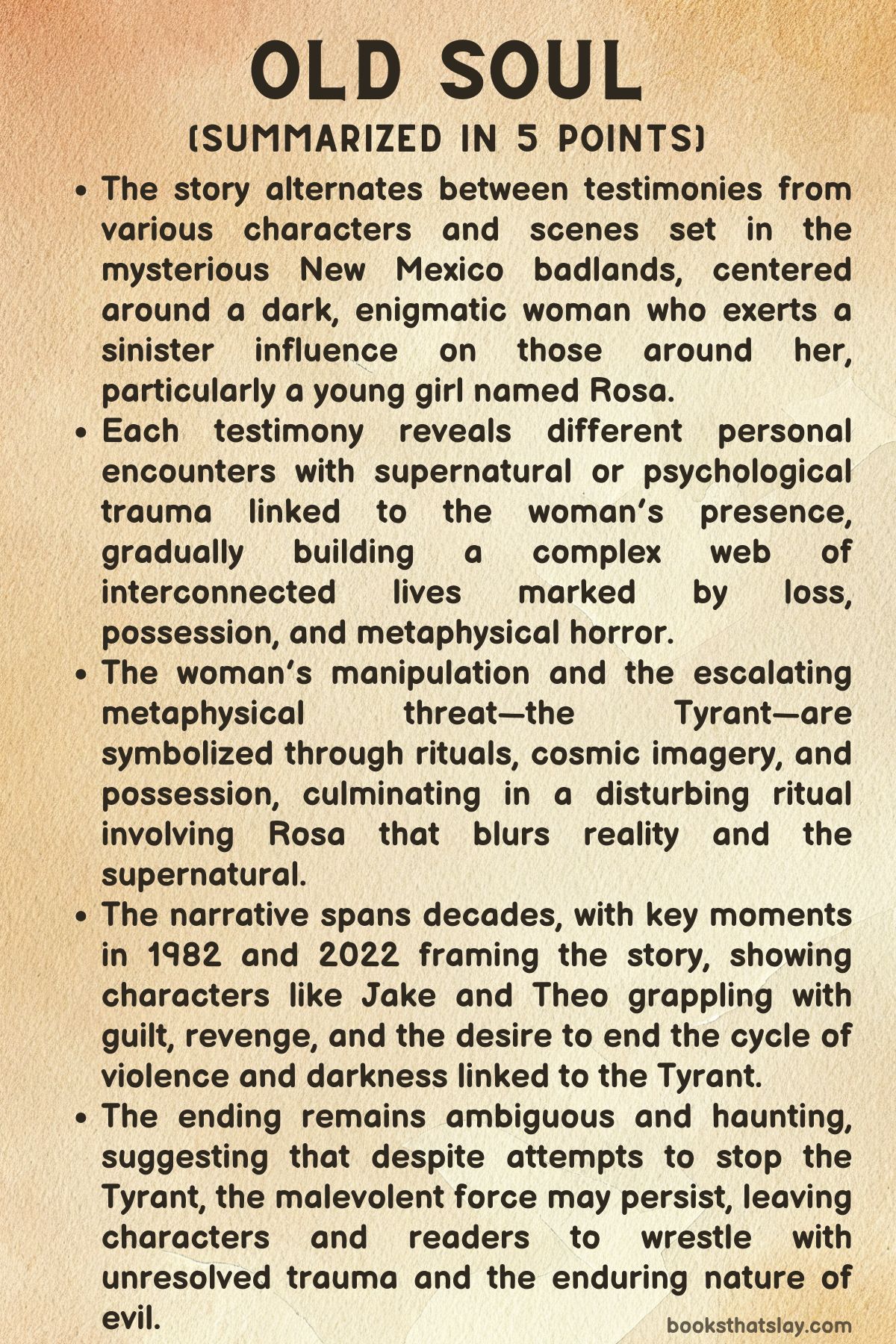

Old Soul by Susan Barker is an unsettling, layered novel that crosses continents and decades to examine the deeply human and eerily inhuman elements of identity, memory, and possession.

The narrative centers on characters tormented by loss, haunted by loved ones who return changed or never return at all, and stalked by a mysterious cosmic presence referred to as “the Tyrant.” Structured as overlapping accounts—testimonies, journals, recollections—the book mixes psychological realism with speculative horror. As it shifts from post-9/11 Tokyo to the American desert, from Cold War Europe to a near-future apocalypse, Old Soul reveals the persistent threat of a supernatural force that survives by inhabiting others. What begins as a quiet meditation on grief evolves into a harrowing story of invasion—of body, mind, and time.

Summary

In the early hours of a 1982 morning in Taos County, a woman named E waits for Venus to rise, describing its beauty and desolation to her partner. This moment, steeped in symbolism, introduces a larger narrative that investigates emotional distance, cosmic horror, and the entanglement between trauma and possession.

The memory of Venus—a planet that rotates so slowly one could walk eternally into sunset—becomes a metaphor for the frozen chase of something unreachable, a haunting that will thread through the rest of the novel.

The story formally begins with Jake, a London schoolteacher stranded at Kansai International Airport. There, he meets Mariko, a successful yet visibly fragile banker.

After a spontaneous evening together, she confesses her long-unspoken guilt surrounding her twin brother Hiroji’s death. In 2011, Hiroji had a breakdown, claiming he’d contacted a godlike being and was being rearranged internally—organs reversed, voices inside him.

After his cryptic final call and a mysterious visit from a woman Mariko refused to let in, he was found dead of an apparent heart defect. Her grief and suspicion remain unresolved.

Jake, haunted by his own past, realizes Mariko’s story echoes what happened to his late friend Lena—another person who spoke of reversed organs, internal invaders, and a strange woman shortly before dying. Mariko, shaken by the similarities, withdraws from contact, leaving Jake to dig further into the strange circumstances alone.

His pursuit of truth leads him to Berlin and to Hiroji’s widow, Sigrid.

Sigrid’s account reveals her life in Kyoto with Hiroji before his descent. A mysterious photographer named Damaris had embedded herself in their social circle under the guise of documenting a butō dance troupe.

She seduced Hiroji and, through invasive conversations, unlocked dark secrets, including a confused, possibly incestuous relationship between him and Mariko. As Hiroji deteriorated mentally and spiritually, Sigrid watched him transform into someone unfamiliar—his behavior increasingly erratic, culminating in grotesque performances on the rooftop and a disturbing game played in a bamboo forest with their young son, Tomo.

Sigrid’s therapist blamed Capgras syndrome—suggesting she imagined Hiroji had been replaced—but Sigrid believed something far stranger. Eventually, Hiroji kidnapped Tomo, and was later found dead near his childhood home.

Tomo, traumatized, claimed a death god had killed his father.

Sigrid fled Japan with her son, trying to rebuild a life in Germany. Her narrative becomes one of uncertainty—did Hiroji suffer psychosis or was he overtaken by something inhuman?

Meanwhile, elsewhere in the New Mexico badlands, another thread begins. A woman named Therese drives Rosa, a teenage girl who dreams of influencer fame, into the desert.

Rosa’s excitement turns to unease as Therese’s true intentions reveal themselves. Therese, afflicted by a bodily decay that hints at parasitic infection, is drawn to Rosa with a predatory hunger.

She recalls a previous victim—another young man taken into the desert, photographed, and ultimately destroyed.

These stories orbit each other across time and space. From Japan to New Mexico, characters are linked not by blood but by shared terror: dreams of cosmic entities, mirrored behavior, strange possessions, and mysterious deaths.

In each timeline, a woman appears—Therese, Damaris, E—always on the edge of death, always leaving devastation behind. Their bodies rot, but they continue.

They are vessels for something older and more powerful.

Jake reappears in the later portion of the book, offering his own testimony. Unable to recover from Lena’s death, he carries her belongings and recounts their past.

Lena’s trauma—abuse, addiction, breakdowns—is mapped through objects. Her relationship with a woman named Marion, a mysterious artist, marks the start of her deterioration.

Marion gifts her an antique hairpin. Shortly after, Lena reports being violated from within, her organs turning against her, something alien having entered her body.

The disturbing details—hollowed-out photos, violent sexual episodes, and reversed organs—echo Hiroji’s fate.

As Jake investigates further, he connects Lena’s torment with others who’ve suffered similar fates. This leads to the discovery of the Dark Web Archive: a collection of photographs showing people like Lena, Hiroji, and many others, all paired with images of Venus.

These photos suggest that the affliction is not unique or isolated—it is part of a ritual, or perhaps a feeding cycle governed by the so-called Tyrant.

The story returns to Theo, an aging sculptor and former lover of E. From her journals, the reader learns that E visited Theo’s home decades after their affair ended, gaunt and dying.

E insisted she was no longer human, hinted at transformation, and disappeared again. Theo’s husband, Wolf, vanishes and returns changed—emotionally distant and physically different.

Eventually, he leaves to protect his family, believing he has been infected by the same force that corrupted E. Theo suspects the Tyrant has taken hold of him.

By 2022, Theo is dying of cancer. Her final journal entries reflect on a life shaped by Eva (E) and the destructive gravitational pull she exerts.

Jake and Eddy, Theo’s stepson, attempt to bait Eva using Rosa as a decoy. The trap fails.

Rosa is overtaken, Jake and Eddy die, and Eva—wounded but alive—vanishes once more.

The epilogue imagines the future: Eva, reduced to a mineralized husk beneath the collapsed mountains of New Mexico, her body calcified but the Tyrant still watching through her. Though the human host is destroyed, the entity persists, perhaps preparing for resurrection.

The world, meanwhile, remains unaware, save for scattered survivors who suspect the truth but cannot speak it.

Through these interwoven accounts, Old Soul constructs a bleak vision of immortality as contagion. Its characters are haunted by those they’ve loved, but also by what those loved ones have become.

The Tyrant functions not as a traditional villain but as a cosmic inevitability—something that feeds on memory, grief, and human frailty. Whether it manifests through psychological collapse or literal transformation, the result is the same: identities are eroded, replaced, and erased.

Yet, the story ends not with catharsis, but with continuation—Eva still alive, still crying, and still in thrall to a force older than history.

Characters

Jake

Jake serves as the connective thread of Old Soul, a character both grounded and unraveling. Initially introduced as a schoolteacher from London, Jake is marked by an underlying restlessness and emotional fatigue that propels him into deeper investigations of the strange and supernatural.

His missed flight and spontaneous meeting with Mariko become the inciting incident of a metaphysical odyssey. Despite being an ostensibly rational figure, Jake is inexorably drawn into a world of inexplicable phenomena—first through Lena, his deceased best friend, and later through his entanglements with Mariko, Sigrid, and Theo.

His character is defined by empathy and a persistent need to make sense of what defies understanding. Jake’s emotional depth emerges through his loyalty to Lena, whose memory he preserves with poignant tenderness, even as he struggles to comprehend her descent into horror.

His research into reversed organs and spiritual possession reflects both a scientific curiosity and a profound desire to preserve the dignity of those lost to madness or supernatural corruption. Jake becomes a quiet martyr to the truth, unable to save those around him but determined to bear witness, even when it leads to his own demise.

Mariko

Mariko is a tightly-wound, haunted woman navigating the collision between repression and collapse. An elegant banker by profession, she epitomizes composure—until her alcohol-induced unraveling reveals a fractured psyche burdened by guilt, familial estrangement, and the traumatic legacy of her twin brother Hiroji’s death.

Mariko’s character is caught between denial and revelation; she suppresses her own emotional wounds while remaining deeply affected by Hiroji’s final moments and his cryptic descent into metaphysical terror. Her recounting of dreams, reversed organs, and a ghostly woman at her door blurs the line between delusion and something far darker.

Mariko’s arc is defined by her refusal to confront what she fears may be true: that her brother’s fate was not simply tragic, but cosmically cursed. In her withdrawal from Jake and her distancing from Hiroji’s widow Sigrid, she embodies a very human instinct—to retreat rather than face the abyss.

Yet her very repression makes her a pivotal figure, one whose memories hold the key to a larger, terrifying narrative of possession and recurrence.

Sigrid

Sigrid is a character steeped in sorrow, strength, and perceptual instability. Her account of life with Hiroji in Kyoto is not only a tale of marital decay but also a descent into something preternatural.

Sigrid begins as a pragmatic wife and mother, tethered to reality, but as Hiroji’s behavior becomes more grotesque and surreal, her grip on normalcy slips. Her struggle to understand whether she’s losing her mind or witnessing a literal transformation in her husband reflects the novel’s central tension between psychological disorder and supernatural invasion.

Diagnosed with Capgras syndrome, Sigrid is told her fears are delusional, yet her instincts—and the horrifying events that follow—suggest otherwise. Her courage in protecting her son Tomo, especially in the face of Hiroji’s final breakdown, renders her heroic.

After Hiroji’s death, Sigrid flees Japan, a refugee from the trauma and mythos that consumed her family. Her narrative is haunted not only by loss but also by a lingering suspicion that the evil they faced was real.

Sigrid is a tragic witness to the collapse of rationality and the encroachment of myth into modern life.

Hiroji

Hiroji is the emotional and spiritual epicenter of the novel’s horror—a man whose transformation reveals the porous boundary between human identity and supernatural infiltration. Initially a charismatic and artistic figure with a deep connection to Kyoto’s butō dance culture, Hiroji’s decline is both psychological and mythic.

Following his encounter with the enigmatic Damaris, Hiroji begins to dissociate, detach, and perform increasingly erratic behaviors. His grotesque rituals, sexual manipulations, and eventual embrace of a Shinigami persona culminate in a terrifying fusion of man and myth.

Yet Hiroji’s character is not simply monstrous—he is also mournful, fractured by guilt, haunted by ambiguous desires involving his sister Mariko, and manipulated by unseen forces. His ultimate fate—death in a forest shrine, witnessed by his traumatized son—cements him as a tragic conduit for the Tyrant’s influence.

Hiroji’s journey is a cautionary parable about spiritual corruption, artistic ambition, and the vulnerability of the self to forces beyond comprehension.

Lena

Lena is Jake’s best friend and the most emotionally devastating casualty of the Tyrant’s influence. From childhood, she is portrayed as resilient yet deeply wounded, surviving maternal abuse and finding solace in her bond with Jake and his father.

Her adulthood is marked by attempts at healing—through AA, modeling, and art—but she remains fragile, especially after meeting the seductive and mysterious Marion. Lena’s possession is portrayed through bodily horror, reversed organs, and psychological fragmentation.

Her downward spiral is rendered with intimacy and aching tragedy, culminating in a haunting voicemail and a death that defies explanation. Lena’s posthumous presence looms over Jake, her fate the catalyst for his quest.

She embodies the novel’s themes of trauma, vulnerability, and the impossibility of fully protecting those we love from invisible predators.

Damaris / Marion

Whether as Damaris or Marion, this woman appears as an emissary of the Tyrant, a shapeshifting succubus whose role is to seduce, infiltrate, and spiritually hollow out her victims. Both Hiroji and Lena fall under her influence, seduced by her allure and ultimately undone by what she represents.

Her method is psychological seduction—drawing out secrets, offering a sense of recognition and understanding, then slowly corrupting. She operates as both artist and predator, a figure who uses creativity as a gateway into the soul.

Damaris’s ambiguity—neither fully human nor fully other—cements her role as the novel’s embodiment of temptation and spiritual degradation.

Therese / Eva / E

Eva, known across time as E, Olga, and Therese, is the story’s most enigmatic and terrifying figure—an immortal vessel of destruction and paradox. She is both deeply human and terrifyingly alien, capable of immense tenderness and unspeakable violence.

As E, she is a lost lover and muse; as Olga, a manipulator; as Therese, a predator hunting young influencers like Rosa. Her existence spans centuries, her transformations linked to a metaphysical entity known as the Tyrant.

Eva’s relationships—whether with Theo, Wolf, or Rosa—end in manipulation, possession, or annihilation. She feeds on others to survive, leaving ruin in her wake.

Yet she is also haunted by her own actions, occasionally expressing remorse or despair. In the end, she becomes a mythic figure: Eve and Lilith, Venus and predator, a fallen star walking among mortals.

Her final image—preserved beneath a mountain, still alive but no longer human—is the ultimate expression of the story’s themes of corrupted immortality and the monstrous cost of survival.

Theo

Theo is the chronicler and conscience of the novel, a sculptor whose journals document her entanglement with Eva and her attempts to reckon with personal and collective trauma. Through her lens, the reader experiences the allure and devastation of Eva’s presence.

Theo’s arc traces her transformation from artist to wife and mother, then to survivor and seer. Her artistic identity becomes both salvation and curse, her sculptures expressions of a soul grappling with metaphysical horror.

Theo’s journal reveals her desire to understand and stop Eva, even as she knows the cost may be her own life. In the end, she is destroyed, her studio and body consumed, but her voice survives in the narrative.

Theo is the novel’s moral center, the witness who dares to see and speak what others suppress.

Rosa

Rosa is the latest, youngest victim in Eva’s long chain of predation. A teenage girl obsessed with astrology, self-actualization, and internet fame, Rosa initially seems shallow—but her innocence and hunger for meaning make her an ideal target.

As Therese draws her into the desert under the pretense of influencer videos, Rosa’s vulnerability becomes increasingly apparent. Her transformation—from cheerful idealist to possessed vessel—is one of the most chilling in the novel.

Rosa becomes the new host of the Tyrant, her body overtaken, her essence erased. Her fate mirrors Lena’s and Hiroji’s, but the youth and promise she embodied make her loss particularly tragic.

Rosa represents the latest iteration in an ancient cycle of destruction.

Wolf

Wolf is Theo’s husband, a grounded, stable presence whose identity is ultimately shattered by Eva’s reappearance. After encountering Eva, Wolf is “flipped,” his personality subtly and then overtly altered, suggesting spiritual or psychic possession.

His departure is an act of love—recognizing that whatever has overtaken him threatens his family—but also a mark of how powerless even the strongest bonds are against the novel’s supernatural forces. Wolf’s character, though less detailed, is crucial in showing how deeply Eva’s corruption can penetrate even the most solid human connections.

Tomo

Tomo, the child of Sigrid and Hiroji, embodies the novel’s lasting trauma. A sensitive and observant boy, Tomo becomes a silent witness to the horrors surrounding him.

His participation in Hiroji’s twisted Shinigami game, his abduction, and his presence at his father’s death forever scar him. Tomo’s silence in later years, particularly around the night of Hiroji’s death, is more chilling than any verbal testimony.

He represents the legacy of possession and trauma—the way darkness imprints itself on the next generation.

Themes

Emotional Estrangement and Isolation

In Old Soul, emotional estrangement emerges as a persistent condition that afflicts nearly every character, regardless of their background or time period. From Mariko’s inability to reconcile her grief and guilt over her twin brother’s death, to Sigrid’s helpless disconnection from Hiroji as he transforms before her eyes, the characters suffer from an unbridgeable gap between themselves and those they love.

This is not simply a matter of failed communication—it is the recognition that there exists something within others that can never be fully understood or reached. Mariko’s metaphor of Venus, a planet so beautiful yet uninhabitable, illustrates this dynamic: relationships promise closeness but deliver distance, as though people are separated not by choice but by cosmic design.

Jake’s loss of Lena, too, is not just a bereavement but a failure to save someone he thought he knew entirely, only to discover there were depths to her experience—whether psychological or supernatural—that he could never enter. Sigrid’s fear that Hiroji is no longer “himself” reveals the terror of loving someone whose essence has become alien.

Even Eva, despite being the thread connecting these lives, is haunted by the knowledge that her own existence causes isolation in others. Her immortality doesn’t grant connection—it enforces solitude.

The consistent inability to truly know or protect another person culminates in the realization that isolation isn’t a temporary state, but an existential truth of being.

Possession and the Loss of Identity

The theme of possession—literal, psychological, or spiritual—permeates the narrative in unnerving ways. Characters lose control of their bodies, their minds, and their moral centers, often without any clear line distinguishing internal collapse from external invasion.

Lena’s story is the most direct expression of this: her belief that something foreign has entered her body and turned her organs is mirrored by the autopsy’s confirmation of reversed organs, blurring the boundary between delusion and reality. Hiroji’s descent follows a similar trajectory: after his contact with Damaris, he becomes emotionally vacant, physically erratic, and psychotically altered, leading to behaviors that defy rational explanation.

Sigrid suspects possession, a suspicion both supported and undermined by her therapist’s diagnosis of Capgras syndrome. These dual possibilities—mental illness versus supernatural takeover—feed the novel’s most terrifying ambiguity.

The Tyrant, a force that operates like a virus of identity, spreads across time and space through Eva’s body and those she touches. Whether it is Jake questioning what happened to Lena, or Theo witnessing her husband changed forever after one meeting with Eva, the novel presents a world where identity is fragile and can be overwritten without warning.

The terror doesn’t lie in monsters with sharp teeth, but in the erosion of selfhood—when the people you know remain in form but have been hollowed out, rewritten, or erased by a force that speaks through them.

Generational Trauma and Inherited Suffering

Old Soul treats trauma not as isolated events but as legacies passed down across generations and lifetimes. The traumas experienced by Lena, Hiroji, Sigrid, and even Rosa are never confined to their immediate timelines.

Instead, they seem inherited, either genetically, emotionally, or metaphysically. Lena carries the scars of an abusive mother, and though Jake offers refuge, the damage seeps into her adult life, eventually compounding into her death.

Hiroji, haunted by guilt and strange visions, performs disturbing rituals that traumatize his son Tomo, who in turn is left mute and broken by the experience. Sigrid attempts to break the chain by fleeing to Germany, but the silence Tomo carries is a chilling inheritance of his father’s fate.

Theodora’s own story shows how the damage wrought by Eva ripples across time, infecting not only her husband and stepson but threatening her grandchildren. Rosa, the latest in a long line of manipulated innocents, becomes the newest vessel of the Tyrant, showing that suffering in this world is not only cyclical but deeply intergenerational.

The novel never offers a definitive origin point for this trauma; instead, it is treated as endemic, systemic, and virally transmitted through acts of love, intimacy, and curiosity. The characters are not just victims of their own choices but inheritors of a cosmic malaise that refuses to end with them.

Obsession and the Destructive Allure of Beauty

Obsession in Old Soul is often disguised as admiration or love, but it quickly becomes corrosive. Beauty—especially female beauty—acts as a powerful catalyst, attracting others only to ruin them.

Mariko is composed and elegant on the surface, but her life is crumbling beneath the pressure of family expectations and loss. Damaris uses beauty as bait, seducing Hiroji and destabilizing his world.

Marion captivates Lena, beginning a spiral of passion and disintegration. Eva, the narrative’s central figure, is the most haunting example.

As E, Olga, and Therese, her beauty appears eternal and preternatural, drawing people toward her even as she destroys them. Theo is unable to resist her allure despite knowing Eva’s proximity portends ruin.

Wolf, too, is seduced and consumed. Beauty here is not superficial—it is a trap, a magnetic field around which destruction orbits.

This obsession distorts perception, leads to self-abandonment, and eventually incites horror. The danger lies not in ugliness or monstrosity, but in the irresistible draw of the sublime, which blinds characters to their impending devastation.

The narrative critiques society’s tendency to idolize aesthetic appeal without understanding the cost, revealing how obsession with beauty—especially when combined with trauma and loneliness—becomes a tool of manipulation and annihilation.

The Collapse of Rationality and the Unreliability of Perception

The story continuously undermines the characters’ ability to rely on reason, casting doubt on what is real and what is imagined. Medical diagnoses like Capgras syndrome or sleep paralysis offer plausible explanations for what characters experience, yet those same experiences also feature physical evidence—reversed organs, violent acts, supernatural synchronicities—that cannot be fully explained away.

Jake is a rational man, a teacher by profession, yet his pursuit of truth about Lena’s death leads him to supernatural explanations he never thought he’d entertain. Sigrid vacillates between accepting her therapist’s clinical perspective and believing Hiroji has been overtaken by something monstrous.

Theo begins her journey grounded in the physicality of art, only to end up facing an archive that suggests her life has always been watched, catalogued, and manipulated by a force outside human understanding. This collapse of rationality leaves characters stranded in liminal spaces where they no longer trust their senses or memories.

Time becomes fluid. Cause and effect blur.

The presence of the Tyrant ensures that logic is never sufficient to confront what they face. The novel builds its horror not from external monsters but from the disintegration of certainty.

When language, science, and memory all begin to fail, what remains is dread—a world where what you see and what is true are never the same thing. This epistemological instability underscores every act of violence and despair, showing that the most terrifying thing is not what we don’t know, but what we think we know and cannot prove.