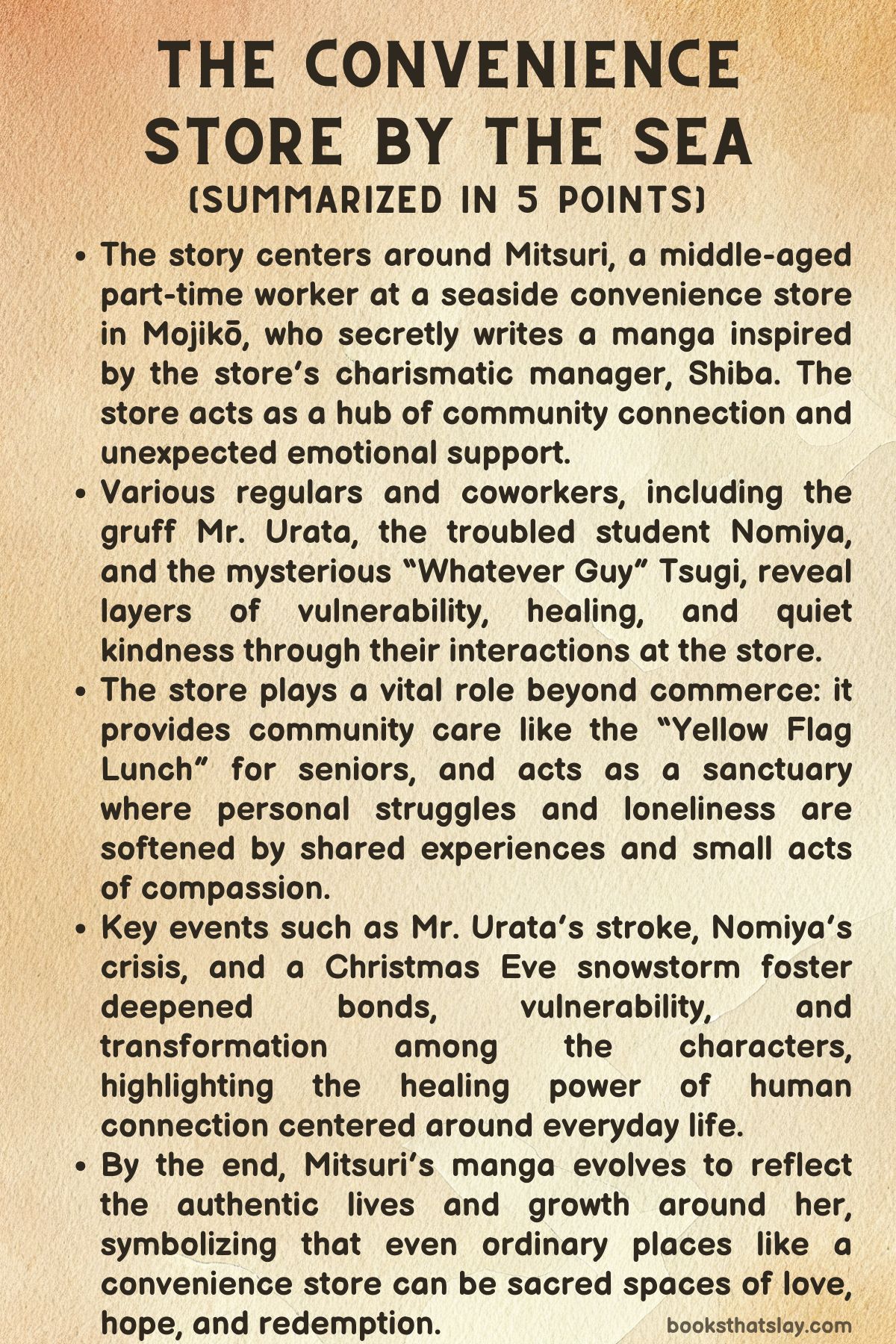

The Convenience Store by the Sea Summary, Characters and Themes

The Convenience Store by the Sea by Sonoko Machida is a tender and reflective novel that finds beauty and meaning in the everyday interactions of people brought together by an unassuming convenience store named Tenderness. Set in the coastal town of Mojikō, the book is less about dramatic plot twists and more about quiet revelations, emotional healing, and the gentle power of community.

Through multiple interconnected character arcs—from a struggling manga artist to a retired man finding new purpose, to a teenager learning the complexities of love and family—the story paints a warm and compassionate portrait of how ordinary places and relationships can profoundly shape one’s life.

Summary

The story begins with Mitsuri Nakao, a housewife and part-time convenience store worker, who finds herself unexpectedly captivated by a charismatic convenience store manager, Mitsuhiko Shiba, during a spontaneous trip to Mojikō. Mitsuri, known for her calm demeanor and love of manga, nicknames him “Phero-Manager” due to his mysterious allure.

This encounter becomes the catalyst for a major shift in her life, prompting her to become more involved with the store and its unusual community of customers and workers.

Tenderness, the convenience store, is no ordinary place. It serves as a vital social center, especially for the elderly and isolated residents.

An initiative called the “Yellow Flag Lunch” allows seniors to receive not just meals but check-ins and human connection. The program is started by a customer named Niseko and becomes a symbol of how the store transcends its role as a commercial hub to become a place of emotional support and mutual care.

Through Mitsuri’s eyes, readers are introduced to a host of unique characters. There’s Nomiya, a university student with a muscled build and a tormented heart, haunted by a past incident involving a former teammate.

There’s also Shōhei, a local guide known affectionately as Old Red, and Tsugi, a junk collector with a gentle soul. When Mr.

Urata, a frequent customer, collapses and is saved thanks to the attentiveness of the store, the emotional stakes of this informal community are laid bare. Nomiya is particularly shaken, his guilt surfacing as he reveals his inability to help a teammate in the past.

Tsugi becomes a comforting figure, helping Nomiya by providing both food and emotional steadiness. In time, it’s revealed that Tsugi is actually Shiba’s older brother, a fact previously concealed due to the frenzy Shiba’s good looks tend to provoke.

This familial link adds emotional weight to Shiba’s character, presenting him as more than just an object of admiration—he’s part of a layered family story, quietly dedicated to his work and his brother.

Parallel to Mitsuri’s arc is the story of Yoshirō Kiriyama, a thirty-three-year-old man who has long dreamed of becoming a manga artist. Working instead as a test-prep teacher, Yoshirō’s life feels hollow and routine until he meets Tsugi at the store.

Tsugi’s passion for curry and simple pleasures awakens Yoshirō to the monotony and passivity of his own life. He reflects on his creative failures and the emotional fallout from a broken friendship with a prodigiously talented peer.

Overwhelmed and disillusioned, Yoshirō decides to leave Mojikō. But just before leaving, he has a heartfelt encounter with Shiba and the older women at the store, who reveal they have always admired his drawings.

Shiba even confesses he used to peek at Yoshirō’s art, and though Yoshirō initially rejects this praise, it leaves a lasting impact.

Yoshirō returns to his childhood home in Ōita, unsure of what to do next. Tsugi soon tracks him down and, through shared meals and open admiration for Yoshirō’s drawings, helps him rethink what it means to be successful.

The encouragement rekindles Yoshirō’s passion. He realizes that creating art to touch others, even if it’s not commercially recognized, is a worthy pursuit.

By the time he returns to Tenderness, he is no longer the same man. He eats his beloved egg sandwiches and curry again, enjoys new coffee blends introduced by the store, and allows himself to feel joy in simply creating.

Yoshirō chooses to keep drawing, not for acclaim, but for the connections his art can foster.

Another thread follows Azusa, a student who stands up to a once-close friend named Mizuki in a tense confrontation. Though frightened, Azusa chooses courage and independence, applying to a prestigious prep school of her own choosing.

Her story culminates in a reunion with Nayuta, a long-lost friend who once received comfort simply from Azusa’s presence. Their emotional meeting at the Tenderness dessert shop restores both girls.

Azusa commits to crafting desserts that bring joy, inspired by the comfort Nayuta once gave her during dark times.

Takiji Ōtsuka’s story unfolds with him navigating retirement, loneliness, and a strained marriage with his wife Junko. His life changes when he meets Hikaru, a young boy who eats alone and faces ridicule at school for not having parents who can attend field day.

Moved by Hikaru’s situation, Takiji offers to be his stand-in grandfather. Training for a three-legged race with Hikaru reignites a sense of purpose in Takiji.

Meanwhile, Junko falls ill, prompting the couple to open up to each other for the first time in years. They make a bucket list together and attend the field day hand-in-hand, embracing their new roles as Hikaru’s surrogate grandparents and affirming their own late-life dreams.

Kōsei, Mitsuri’s son, harbors suspicions that his mother is having an affair. With the help of his perceptive classmate Misumi, Kōsei discovers that Mitsuri is mentoring a younger manga artist, not cheating.

Misumi, who has experienced her own emotional trauma following her parents’ divorce, helps Kōsei develop emotional intelligence and maturity. Through this journey, Kōsei begins to see his parents as complex individuals who made sacrifices and found joy together in pursuing their passions.

Though he starts to fall for Misumi, she admits to liking someone else. When her confession is met with rejection, Kōsei offers comfort, but a misunderstanding leads to a falling out between them.

Kōsei’s internal growth deepens further when Kozeki, the boy Misumi liked, quietly acknowledges that Kōsei had understood the emotional depth of a photograph others had misread.

The final part of the book introduces Jewel, the younger sister of Mitsuhiko and Tsugi, who arrives at the Tenderness store in a vulnerable state. Mitsuri takes her in, offering support and care.

Jewel’s uncertainty mirrors the confusion many younger characters face in the novel, reinforcing the theme of generational empathy. In the end, characters from different backgrounds, ages, and emotional wounds come together around the shared rituals of meals, kindness, and presence.

The Convenience Store by the Sea closes on a hopeful note, showing how even seemingly mundane places can become spaces of deep transformation. Through food, art, conversation, and shared vulnerability, the Tenderness store becomes a place where people not only shop but also grow, forgive, and begin again.

Characters

Mitsuri Nakao

Mitsuri Nakao is the heart of The Convenience Store by the Sea, a housewife and part-time convenience store worker whose layered identity slowly unfolds into one of quiet strength and emotional generosity. At first glance, Mitsuri leads a modest life filled with domestic responsibilities and a personal passion for manga.

Her journey begins almost whimsically—a solo road trip triggered by subtle social humiliation—but this impulsive act becomes a portal into a profound life transformation. Mitsuri’s fascination with the alluring manager Mitsuhiko Shiba draws her into the Golden Villa Tenderness store, where her nurturing nature finds fertile ground.

She becomes more than a clerk; she is a caregiver, a quiet observer, and an emotional anchor for the store’s unconventional community. Her empathy and sense of responsibility make her instrumental in defusing emotional tensions and deepening the web of human connections, such as when she reaches out to Tsugi to support a guilt-ridden Nomiya.

Her role evolves further when she becomes a mentor to younger people like Kōsei and even takes in Jewel, the vulnerable younger sister of the Shiba brothers. Through her emotional insight and gentle wisdom, Mitsuri becomes a source of healing and inspiration—both within the store and within her own family.

Her transformation is not about reinventing herself radically but about reclaiming her joy and purpose through small, meaningful acts that ripple outward.

Mitsuhiko Shiba

Mitsuhiko Shiba, affectionately dubbed “Phero-Manager” by Mitsuri, exudes a quiet charisma that initially appears almost mythical. Women flock to him, seemingly bewitched by his effortless charm, yet beneath the surface lies a deeply earnest and selfless individual.

As the manager of the Tenderness store, Shiba is not merely a workplace supervisor but a custodian of community values. His dedication to creating a space where people feel seen and cared for—evident in the “Yellow Flag Lunch” initiative and his concern for each customer’s wellbeing—reveals a man of immense emotional depth.

He carries his past with a stoic grace, concealing his familial connection to Tsugi to avoid inviting undue attention, and his admiration for Yoshirō’s sketches speaks to his appreciation for unspoken beauty and talent. Shiba’s emotional intelligence makes him a gentle but firm guide to the lost souls who enter his orbit.

Though he remains somewhat enigmatic, his consistent actions define him: he supports without fanfare, praises without expectation, and provides without demand. Shiba, ultimately, is not just a heartthrob or a boss; he is a quiet architect of renewal for those around him.

Tsugi Shiba

Tsugi Shiba, the older brother of Mitsuhiko, emerges as a seemingly eccentric yet emotionally grounded figure. Introduced through his love for curry and idiosyncratic eating habits, Tsugi quickly reveals himself as a sage wrapped in oddball clothing.

His interactions with Yoshirō are especially transformative. He is one of the few characters who confront others’ self-doubt not with pity but with affirmation rooted in lived experience.

Tsugi’s belief that persistence itself is a form of talent reshapes Yoshirō’s defeated worldview. He acts as an emotional compass, guiding the disoriented—be it Nomiya, Yoshirō, or even Jewel—toward self-acceptance.

Though Tsugi has kept a low profile and shunned the spotlight his brother attracts, his quiet wisdom and humble lifestyle offer another form of heroism: one built on attentiveness, emotional labor, and nourishment—both literal and metaphorical. Tsugi does not need admiration to be impactful; his strength lies in offering sanctuary through food, conversation, and presence.

His understated mentorship defines much of the story’s emotional resonance.

Yoshirō Kiriyama

Yoshirō is a man suspended between aspirations and resignation, a would-be manga artist who abandoned his dreams for the security of a teaching job. His story in The Convenience Store by the Sea is a moving portrait of failure, self-loathing, and slow rebirth.

Haunted by his falling out with a talented childhood friend and his lack of success in manga contests, Yoshirō retreats into a life of minimal risk and muted pleasure. His chance encounter with Tsugi acts as a jolt to his sensibilities, and over time, his defenses begin to erode.

Yoshirō’s emotional arc crescendos with acts of both vulnerability and defiance—quitting his job, fleeing home, crying in public. It is only when he is seen and affirmed by others—Shiba’s secret admiration, Tsugi’s praise, the warmth of community women—that he begins to confront his narrative of failure.

His rediscovery of the joy in drawing not for acclaim but for emotional resonance signifies a profound personal evolution. By choosing to create again, Yoshirō reclaims not just his dream but also his capacity for connection, resilience, and joy.

Azusa

Azusa’s journey is one of quiet courage and emotional reorientation. Once bound by familial and societal expectations, she finds herself at a crossroads following a confrontation with a former friend.

Rather than giving in to shame or rage, Azusa asserts her right to self-determination, applying to a school of her own choosing. Her transformation is sealed by her reunion with Nayuta, whose gratitude for Azusa’s consistent presence during hard times validates the emotional labor Azusa had unknowingly offered.

Inspired by this bond, Azusa anchors herself in a newfound dream—to craft desserts that serve as emotional sustenance, much like their ritual visits to Tenderness. Her growth is emblematic of the novel’s theme of love as nourishment and strength as gentleness.

Takiji Ōtsuka

Takiji is the embodiment of late-life redemption. A retired man grappling with feelings of abandonment and irrelevance, Takiji finds unexpected purpose through an unlikely friendship with Hikaru, a young boy mocked for not having a family to support him.

By offering to be Hikaru’s grandfather for the school event, Takiji rediscovers vitality, responsibility, and joy. This newfound role catalyzes healing within his own marriage as well.

Caring for his ailing wife Junko allows Takiji to engage emotionally in a way he never did before. Their mutual confessions and plans to pursue a bucket list reflect a rekindled partnership rooted in vulnerability.

Takiji’s evolution from bitterness to compassion marks one of the novel’s most tender arcs, demonstrating that love and growth are always within reach—regardless of age.

Kōsei

Kōsei represents the novel’s rawest emotional terrain—a teenager bewildered by love, disillusioned by his parents, and overwhelmed by his own insecurity. His suspicion that his mother Mitsuri is cheating reflects both a projection of his own fears and a deeper misunderstanding of adult emotional complexity.

Through his bond with Misumi, who has experienced real familial trauma, Kōsei begins to distinguish between assumptions and truths. Discovering his mother’s passion for manga and witnessing the genuine partnership between his parents broadens his emotional lexicon.

While his growing affection for Misumi is not reciprocated, the experience teaches him about rejection, empathy, and the importance of emotional authenticity. Kōsei’s journey toward maturity is neither linear nor complete, but it is deeply human—defined by learning, hurting, and continuing.

Mifuyu Misumi

Misumi is a stoic and emotionally mature counterpart to Kōsei. Shaped by her parents’ divorce and her mother’s infidelity, she exudes a calm exterior but carries emotional weight beneath it.

Her willingness to guide Kōsei through his confusion—despite her own unresolved pain—demonstrates a deep capacity for empathy. Misumi’s own heartbreak, particularly her failed confession to Kozeki, reveals her vulnerability and longing for emotional reciprocity.

Her falling out with Kōsei further underscores her need for genuine understanding rather than condescension. She is a figure of emotional integrity, someone who is cautious but not closed, resilient but not unfeeling.

Jewel

Jewel’s arrival at the Tenderness store marks the novel’s closing chord of emotional openness. As the younger sister of the Shiba brothers, she represents a new generation navigating the anxiety of finding one’s place in the world.

Her illness, uncertainty, and vulnerability are met with Mitsuri’s compassion, reinforcing the intergenerational themes of care and healing. Jewel’s presence provides Mitsuri another opportunity to mentor and support, while also hinting at the enduring cycle of guidance, hope, and belonging that defines the Tenderness community.

Though her arc is brief, it is a powerful reminder that sometimes simply being accepted is the first step toward healing.

Themes

The Quiet Heroism of Everyday Connection

The Convenience Store by the Sea centers its emotional weight on how small gestures and quiet interactions form the bedrock of communal care. At the heart of the Tenderness convenience store lies a deep moral compass that guides not only commerce but emotional outreach.

Programs like the Yellow Flag Lunch offer more than food—they provide a lifeline to the elderly and isolated, subtly blending routine consumer activity with watchful companionship. Mitsuri’s attentiveness, Tsugi’s calm generosity, and Shiba’s silent encouragement all coalesce into a portrait of everyday heroism not defined by grand acts but by consistent, compassionate presence.

These interactions counter societal alienation, especially for those on the margins—be it retirees like Takiji, emotionally stranded students like Kōsei, or weary dreamers like Yoshirō. The narrative insists that such human touchpoints, however unassuming, carry a transformative power.

The store becomes not only a hub of transactions but a spiritual sanctuary, and its clerks are not merely workers but guardians of emotional well-being. Whether it’s finding a collapsed customer just in time or recognizing the sadness behind a withdrawn patron’s eyes, the book highlights that care is a daily practice, executed quietly and without expectation of reward.

The Fractured Self and the Rediscovery of Purpose

Yoshirō’s story brings into focus the quiet devastation of artistic stagnation and the long road toward reclaiming self-worth. His failure to commit fully to either his job or his dream, paired with unresolved bitterness toward his more successful friend Mogi, illustrates the paralyzing nature of self-doubt.

When his students question his relevance and Shiba’s praise unsettles rather than uplifts him, Yoshirō’s identity fractures further. He is neither teacher nor artist in his own eyes.

The turning point emerges through his interactions with Tsugi and the community at Tenderness, where validation becomes detached from professional recognition and is instead rooted in personal resonance. A drawing that once felt meaningless begins to matter again, not because it wins contests, but because it speaks to someone.

Tsugi’s admiration for a Musashi vs. Kojirō sketch, along with Shiba’s quiet appreciation, forces Yoshirō to re-evaluate the idea that persistence itself can be a form of success.

The narrative does not conclude with grand success or artistic fame, but with the gentler, more sustaining realization that creation need not justify itself with external acclaim. Rediscovering purpose becomes less about reclaiming a dream and more about re-anchoring the self in something authentic and sustaining.

Emotional Maturity Through Misunderstanding and Repair

Kōsei’s internal conflict and its ripple effect across his relationships reveal a complex portrayal of adolescence, especially as it pertains to assumptions, misinterpretations, and emotional learning. Convinced his mother Mitsuri is being unfaithful, Kōsei begins his journey from suspicion and cynicism.

His understanding of love is immature and influenced by fear—fear of abandonment, fear of vulnerability, and fear of being unworthy. Through his interactions with Misumi, who carries her own emotional scars, Kōsei starts to grasp the layered nature of human emotion.

He misreads Mitsuri’s joy and secrecy as betrayal, only to later learn that her manga passion is a suppressed part of her identity finally being nurtured with her husband’s support. Misumi’s confession of unrequited love, Kozeki’s emotional aloofness, and Kōsei’s own missteps with empathy all contribute to his slow growth.

The novel doesn’t reward him with romantic closure but rather maturity—the ability to see others as nuanced, the humility to acknowledge his flaws, and the emotional resilience to move forward. This theme underscores the necessity of misunderstanding as a crucible for growth.

In letting go of absolute judgments and allowing for ambiguity, Kōsei becomes more emotionally literate, empathetic, and capable of real connection.

Intergenerational Compassion and Late-Life Renewal

Takiji’s narrative arc exemplifies how life’s second half can be just as fertile with growth and transformation as its first. Retired and feeling displaced in his marriage, Takiji initially stews in bitterness toward his wife’s autonomy and the absence of purpose in his routine.

His accidental connection with Hikaru, a boy who mirrors his loneliness, becomes the catalyst for emotional reawakening. Their shared training for a school event, a seemingly frivolous activity, evolves into something more profound: a rediscovery of joy, responsibility, and emotional relevance.

Simultaneously, his wife Junko’s illness prompts an emotional reckoning within their marriage. Their relationship, once burdened by silent disappointments and unmet expectations, becomes a space of vulnerability and mutual support.

They each acknowledge the constraints they imposed on one another, and in that confession, they find new ground for companionship. By adopting Hikaru as their symbolic grandchild, they create a new relational dynamic that affirms their continued ability to nurture and be nurtured.

The idea that redemption and emotional reengagement can come late in life is handled without sentimentality. Instead, it’s portrayed as a steady shift brought on by small acts of reaching out, listening, and choosing to participate again.

This theme highlights that compassion is not limited by age, and that connection can reinvigorate even the most settled, fatigued spirits.

Feminine Agency and the Assertion of Personal Identity

Azusa and Mitsuri’s respective arcs explore the assertion of selfhood in a world that often seeks to define women by external expectations—be it through roles like mother, wife, friend, or student. Azusa’s quiet resistance against the prescribed path of school and peer compliance is not driven by anger but by conviction.

Her refusal to physically retaliate against Mizuki, her application to a different school, and her choice to find fulfillment in creating desserts are acts of reclamation. She steps away from roles that suffocate and chooses paths that inspire.

Similarly, Mitsuri’s layered life as a housewife, mother, manga lover, and part-time worker pushes against one-dimensional representations. Her husband’s support and her son’s eventual understanding do not render her fulfillment any less self-initiated.

She claims her joy, her time, and her right to creative expression without needing anyone’s permission. These portrayals of feminine agency are subtle and complex.

They reject grand narratives of rebellion and instead honor the everyday decisions through which women reassert control over their identities. The power of these characters lies in their ability to hold space for others while still protecting their dreams.

The novel suggests that feminine strength is often expressed not through confrontation but through a deliberate and sustained act of self-definition.

Food as Emotional Language and Cultural Anchor

Throughout The Convenience Store by the Sea, food emerges as a critical emotional and narrative device. Whether it’s Mitsuri’s egg sandwiches, Tsugi’s peculiar pickle-curry experiments, or Nayuta and Azusa’s shared desserts, meals are never just about sustenance.

They are acts of communication, affection, and healing. Tsugi uses food to comfort a grieving Nomiya, bringing not only warmth but wordless affirmation.

For Yoshirō, sandwiches and curry symbolize memory and belonging, reconnecting him with Tenderness and his art. Takiji’s race preparation with Hikaru includes shared meals that help establish their bond, while Azusa’s commitment to dessert-making reflects her dream of offering comfort and joy to others.

Even when characters struggle to speak their feelings, food facilitates expression. It is through shared meals that emotional barriers soften, misunderstandings ease, and trust builds.

Moreover, the local flavor of Mojikō—its cafes, convenience store snacks, and community lunches—grounds the story in a tangible cultural landscape. Food becomes the heartbeat of social life, and its preparation and sharing represent values of care, memory, and connection.

The characters’ relationship to food encapsulates their internal states and their desire to communicate love, gratitude, and reconciliation. It underscores that nourishment is as much emotional as it is physical, and that the act of feeding others is also an act of emotional offering.