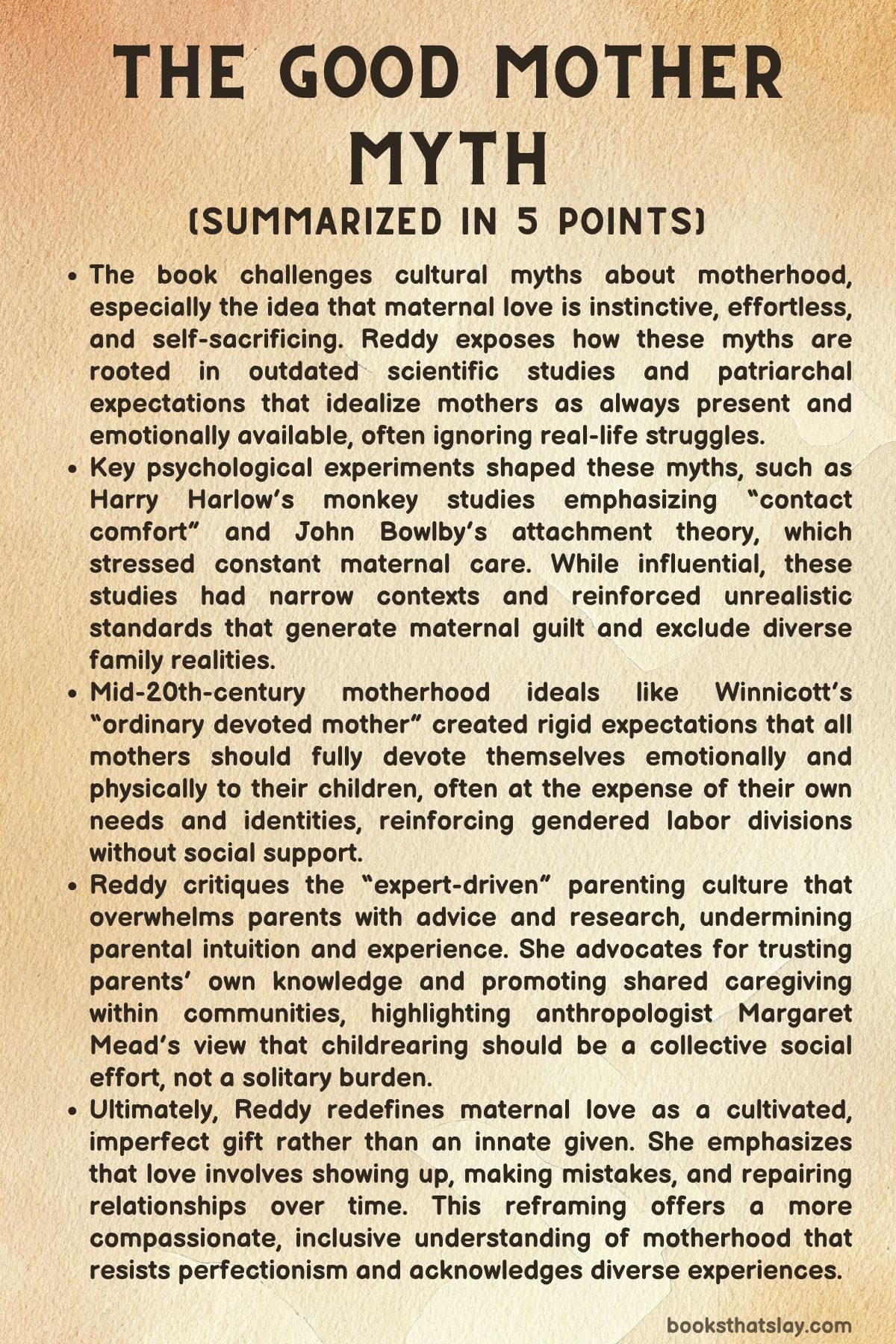

The Good Mother Myth Summary, Analysis and Themes

The Good Mother Myth by Nancy Reddy is a multifaceted and introspective collection that blends personal narrative, scientific history, and cultural critique to reexamine dominant ideals of motherhood. Rather than reinforcing traditional images of maternal perfection, Reddy scrutinizes the social, psychological, and academic forces that have created and sustained such expectations.

Drawing on historical figures like Harry Harlow, John Bowlby, Donald Winnicott, and Margaret Mead, she reclaims the narratives of mothers, caregivers, and marginalized women whose lives and contributions were often ignored or distorted. At its core, the book invites readers to imagine maternal love not as an innate instinct or moral burden, but as a learned, relational act rooted in care, complexity, and community.

Summary

The Good Mother Myth begins with Nancy Reddy’s personal account of entering motherhood—an experience marked by physical pain, sleep deprivation, and deep emotional turmoil. Her first child, Penn, is inconsolable in the early days, and Reddy quickly finds that the ideals she had internalized about what a “good mother” should be leave her feeling inadequate and isolated.

Nursing is painful, bonding is elusive, and instead of an intuitive connection, she is met with frustration and despair. This personal struggle becomes a lens through which she examines the broader social and scientific systems that have shaped maternal expectations.

She revisits the work of psychologist Harry Harlow, best known for his controversial experiments with rhesus monkeys. Harlow’s studies suggested that warmth and comfort, rather than sustenance, were central to attachment—infant monkeys preferred a soft, cloth surrogate over a wire one that provided milk.

While this research challenged older, more clinical ideas of parenting, it was culturally reinterpreted in ways that reinforced rigid ideals of constant, feminine caregiving. Reddy points out that the complexity of Harlow’s findings was lost, and instead, the “cloth mother” became a symbol of unwavering maternal availability and sacrifice.

Moreover, the women involved in this research, including Harlow’s own wife Clara, were erased from the historical record.

From Harlow, the narrative transitions to John Bowlby, who institutionalized attachment theory and solidified the cultural notion that children needed continuous care from their biological mothers. Bowlby’s conclusions, widely adopted by institutions like the World Health Organization, painted maternal absence—regardless of circumstance—as a psychological risk to children.

His ideas took root in the postwar era’s conservative gender politics, framing mothering as a woman’s primary, even sacred, responsibility. These theories were often backed by deeply flawed or limited studies, yet their influence persists in contemporary parenting discourse.

Reddy parallels these theoretical histories with her own lived experiences. She describes the emotional toll of postpartum care, the inequities in caregiving between her and her husband, and the silence surrounding maternal needs.

The expectation of maternal self-erasure—being wholly consumed by the baby—becomes a pressure cooker that leads to breakdowns and internalized shame. When she does reach out for support, such as from her own mother or through friendships with other mothers, she finds moments of relief that challenge the dominant narrative.

These interactions help her recognize that care can be shared, and that good mothering doesn’t mean perfect isolation.

Jeanne Altmann’s baboon studies offer a compelling contrast to Harlow’s monkeys. Altmann, whose fieldwork focused on cooperative parenting among baboons, found that social support was vital to infant survival.

This research undermines the Western notion of the mother as sole caregiver and instead offers a model of communal maternal care. Reddy connects this to her own childhood experiences in a household where her mother and aunt shared caregiving responsibilities, illustrating how such collaboration can offer emotional and practical benefits.

The book continues with an examination of figures like Donald Winnicott, who popularized the idea of “primary maternal preoccupation”—a mother’s deep, instinctive emotional tuning to her baby’s needs. Through public broadcasts and writings, Winnicott contributed to the myth that motherhood is biologically driven and all-consuming.

Reddy critiques this notion by showing how Winnicott’s personal and professional life benefitted from the women around him, particularly Clare Britton and his first wife, Alice, who were instrumental in shaping his work yet remained uncredited.

This pattern of male scientists gaining recognition while sidelining women recurs throughout the book. Reddy highlights the ways women like Mary Ainsworth were scrutinized for being childless, while men like Bowlby and Harlow were celebrated despite being emotionally or physically absent from their own families.

She challenges the idea that maternal wisdom is only valid when filtered through male authority or when it fits a narrow mold of biological determinism.

In one especially revealing scene, Reddy attends a “Milk and Mimosas” gathering with other mothers. There, she observes a friend openly bottle-feeding her baby with formula—something Reddy had long viewed as a moral failure.

This moment becomes a revelation: the idealized image of maternal purity and sacrifice does not accommodate the realities of exhaustion, financial constraint, or personal choice. By acknowledging the value of this other mother’s approach, Reddy begins to let go of the rigid expectations she had imposed on herself.

The narrative also explores the generational inheritance of maternal identity. Through the lives of her own mother and grandmother, Reddy examines how each generation of women navigated the limits and possibilities of motherhood.

Her grandmother, Jeannie, is portrayed as a capable and ambitious woman who, despite her talents, was funneled into domesticity. Her dreams of working in banking were cut short by marriage and health issues, and she lived within a narrow sphere defined by mid-century norms.

Her mother, though shaped by these same forces, sought to parent differently, drawing on books and emotional openness. These family histories serve not only to contextualize Reddy’s own struggles, but to trace how maternal ideals evolve—and how they constrain.

Margaret Mead emerges as a crucial counterpoint to the Western parenting model. Her anthropological work revealed that caregiving structures in other cultures were often communal and flexible.

Mead herself raised a daughter in a multi-generational, multi-partner household and continued her intellectual work alongside mothering. Reddy presents her as an example of a maternal identity that encompasses ambition, shared responsibility, and nonconformity.

Mead’s life offers a vision of caregiving as collective rather than individual, resisting the myth of the solitary, sacrificial mother.

As the narrative moves into the author’s second pregnancy and postpartum period, there is a shift in tone. Although still challenging, this time the experience is tempered by lessons learned and a broader support system.

Yet the burden of invisible labor remains, and it’s only during the COVID-19 pandemic—when stress reaches a breaking point—that her partner finally begins to shoulder equal responsibility. This change is not presented as a miracle cure, but as a hard-earned evolution that underscores the book’s core argument: caregiving is not instinctual, but learned through effort, presence, and shared commitment.

The Good Mother Myth ultimately dismantles the culturally enshrined narrative of maternal perfection. It calls for a redefinition of love and parenting—one that includes imperfection, reciprocity, and the full humanity of mothers.

Through personal testimony, historical recovery, and cultural critique, Nancy Reddy offers an alternative vision of motherhood: not as an impossible ideal, but as a living, evolving practice shaped by relationships, not rules.

Analysis of the People in the Book

The Narrator

The narrator of The Good Mother Myth serves as the emotional and intellectual center of the essay, guiding readers through the tangled landscape of new motherhood, cultural expectations, and academic critique. Her voice is unflinchingly honest, revealing the physical and emotional upheavals she experiences in the wake of childbirth and the early days of parenting.

From sleepless nights and the agony of breastfeeding to the psychic toll of feeling like a failure, she lays bare the vulnerability of early maternal life. But her character is not just a repository of struggle; she is also a relentless thinker.

She connects her personal pain to broader historical and cultural narratives, exploring how psychological theories—especially those of Bowlby, Winnicott, and Harlow—have shaped what it means to be a “good mother. ” Her journey is one of intellectual reclamation and emotional rebuilding.

Through community, friendship, shared labor, and academic critique, she begins to loosen the grip of impossible ideals and forge a new, more inclusive vision of mothering—one that embraces imperfection, interdependence, and self-compassion. The narrator’s evolution from guilt-ridden isolation to collective healing makes her a deeply compelling and multi-dimensional figure.

Penn

Penn, the narrator’s first child, plays a pivotal though largely symbolic role in the narrative. He is not so much developed as a full character but rather becomes the mirror through which the narrator reflects on her perceived successes and failures.

His relentless crying, his need for constant attention, and his resistance to soothing are described not only as stressful but also as accusatory, making the narrator feel inadequate and incompetent. Yet Penn also acts as a catalyst for the narrator’s transformation.

Her growing understanding that Penn’s discomfort is not a direct indictment of her maternal worth becomes a critical turning point. Over time, Penn becomes associated with the hard-earned lessons of motherhood—that love is not automatic, that bonding can be slow, and that caregiving is not the exclusive domain of biological instinct.

Though he remains a quiet presence in terms of dialogue or agency, his impact is immense: he forces his mother to confront the myths she has absorbed and ultimately guides her toward a more forgiving, flexible maternal identity.

Smith

Smith, the narrator’s partner, embodies the complex dynamic between shared responsibility and cultural conditioning in parenting. His initial withdrawal from nighttime parenting and emotional labor is depicted not with animosity but with frustration and sadness.

He, too, is overwhelmed, but the narrative makes it clear that the societal script has not trained him for the intimacy of caregiving in the same way it has trained the narrator. Over time, Smith becomes a more involved and empathetic partner, especially after the birth of their second child and during the pandemic-induced crisis.

His gradual transformation—stepping in more fully, learning to share the invisible labor, and acknowledging the emotional toll of motherhood—mirrors the central argument of the essay: caregiving is not instinctual but learned. Smith’s evolution not only relieves the narrator but also demonstrates the power of partnership in dismantling the myth of maternal singularity.

He becomes a figure of possibility—a flawed but learning co-parent who, through engagement, helps redefine what parenting can look like.

Jeannie

Jeannie, the narrator’s grandmother, appears as a ghostly but potent figure whose life story offers a historical backdrop to the contemporary maternal struggle. Raised under the restrictive ideals of 1950s womanhood, Jeannie is portrayed as intelligent and ambitious, with early success in banking that is ultimately thwarted by marriage, childbirth, and societal expectations.

Her trajectory reflects the broader cultural narrative of postwar domesticity, in which women were funneled into narrow definitions of success centered on motherhood and homemaking. While she outwardly conforms, her inner complexity and early achievements hint at a life curtailed by structural limitations.

Jeannie’s story is not offered as a cautionary tale but as a reminder of the lineage of compromise that shapes maternal identity. Her presence in the essay provides the narrator with a sense of inherited struggle and deepens the critique of how historical forces mold individual destinies.

In reflecting on Jeannie, the narrator finds both grief and continuity, recognizing how her own choices are tethered to—and resisting—those of the women who came before her.

The Fellow Mother at “Milk and Mimosas”

This unnamed woman emerges in a brief but revelatory scene that profoundly shifts the narrator’s understanding of maternal judgment and choice. When she openly mentions feeding her baby formula, something the narrator once viewed as a betrayal of “good mother” ideals, the moment cracks open the narrator’s internalized dogma.

The woman’s casual defiance of breastfeeding orthodoxy becomes an emblem of self-trust and maternal agency. She does not seek validation or defend her choice; she simply embodies it.

This encounter introduces the narrator to a different model of motherhood—one based on self-knowledge rather than compliance. The woman becomes a foil to the narrator’s early self-doubt and a catalyst for change.

In her presence, the narrator begins to question the rigidity of her own beliefs, learning that mothering can be done many ways and that no single method guarantees—or negates—love. This seemingly minor character plays a pivotal role in the narrator’s growing acceptance of plurality in maternal practice.

Margaret Mead

Though not a character in the traditional narrative sense, Margaret Mead is resurrected through the narrator’s intellectual exploration as a symbol of alternative maternal ideology. Her anthropological work and unconventional household offer a counterpoint to the individualistic, sacrificial vision of motherhood propagated by figures like Bowlby and Winnicott.

Mead’s advocacy for collective caregiving and her personal practice of raising her daughter within a network of adults, friends, and fellow scholars provides a model that honors both maternal ambition and child welfare. Mead stands as a beacon of possibility, an intellectual ancestor who validates the narrator’s longing for a maternal identity that includes complexity, collaboration, and public life.

Her inclusion in the narrative reinforces the idea that there have always been models of care beyond the nuclear family and the self-erasing mother—and that these models have simply been overshadowed or erased by dominant cultural scripts.

The Academic Mothers and Forgotten Women

Scattered throughout the essay are the voices and silences of other women—Clare Britton, Alice Winnicott, Jane Spock, Ursula Bowlby—whose contributions to parenting theory or familial care were sidelined, minimized, or entirely erased by the patriarchal structures of their time. These women serve as a collective chorus, haunting the margins of the official record.

The narrator mourns their absence and restores their presence, using their stories to underscore the essay’s broader argument about gender, knowledge, and power. They embody the tension between lived experience and academic theory, between contribution and recognition.

By resurrecting their names and stories, the narrator positions herself within a lineage of overlooked maternal thinkers and caregivers. Their marginalization reinforces the central critique of The Good Mother Myth: that mothering is too often defined by those who have never done it, while those who live it remain unseen.

Their presence, though faint, infuses the essay with a moral urgency to reclaim maternal narratives and redistribute authority.

Analysis of Themes

Maternal Identity and the Burden of Perfection

The narrative confronts the emotional and cultural burdens placed on modern mothers to perform motherhood flawlessly. From the earliest scenes of the narrator’s postpartum experience, there is a sense of desperation to align with internalized ideals about what it means to be a “good mother”—expectations shaped not only by familial norms but also by decades of psychological theory.

The narrator experiences profound guilt when her baby cries inconsolably, or when nursing becomes painful rather than joyful. These moments reflect a deeper belief that her identity is failing if her caregiving is not seamless.

The narrative reveals how these impossible standards are a result of not just personal insecurity, but inherited narratives that valorize maternal self-sacrifice. Scholars like Bowlby and Winnicott suggested that maternal care should be instinctive, automatic, and biologically determined, and this notion morphs into a societal expectation that good mothers must always be nurturing, selfless, and emotionally available.

The narrator’s growing realization that mothering is not intuitive—and that caregiving can be shared, imperfect, and still valid—undermines the myth of maternal perfection. Her ultimate recognition that love is formed through sustained effort, repair, and community support becomes a radical redefinition of what it means to mother well.

The Gendered Construction of Scientific Authority

The essay presents a sharp critique of how male-dominated psychological and scientific institutions have defined and constrained maternal roles. Figures like Harry Harlow, John Bowlby, and Donald Winnicott emerge not only as authorities in child development, but as creators of cultural doctrine about maternal worth.

Their research, particularly Harlow’s monkey studies and Bowlby’s attachment theory, is shown to have been imbued with gendered assumptions, despite often being based on ethically troubling or narrowly designed studies. Harlow’s cloth mother became a symbol of comforting femininity, ignoring his broader conclusions that love and attachment can arise from various forms of care.

Meanwhile, Bowlby’s theories were widely disseminated through influential institutions like the World Health Organization, reinforcing the belief that mothers alone are responsible for their children’s emotional development. The essay also exposes the marginalization of women within this academic landscape.

Clara Harlow, Clare Britton, Ursula Bowlby, and Alice Winnicott are all women whose ideas, labor, or intellectual contributions were minimized or excluded. The essay reclaims these voices and contrasts their experiences with the reverence afforded to their male counterparts, illuminating the gendered gatekeeping in both science and culture.

This theme dismantles the legitimacy of rigid maternal ideals by showing how deeply they were shaped by biased systems of knowledge production.

Maternal Love as a Learned and Communal Practice

Rather than accepting the notion of maternal love as instinctual and biologically automatic, the essay argues that love is built through practice, support, and shared responsibility. The narrative returns frequently to examples from both human experience and animal studies to show that caregiving is not innate but modeled, learned, and negotiated.

The story of Kawan, the zoo orangutan who could not care for her baby due to a lack of maternal modeling, provides a powerful metaphor for the narrator’s own early struggles. The eventual success of Keju’s upbringing through the intervention of a “super surrogate,” Madu, highlights the potential of communal caregiving in both human and animal settings.

Additionally, the narrator’s experiences with fellow mothers—particularly during moments of shared vulnerability, such as at the “Milk and Mimosas” gathering—demonstrate how emotional support and candidness can create a more sustainable model of maternal love. This redefinition of love moves away from the isolated, sacrificial mother and toward a vision of parenthood that includes partnership, friendship, and systemic support.

In acknowledging that love can be messy, delayed, or mediated through struggle, the narrative constructs a more inclusive and compassionate vision of what mothering can look like.

The Erasure and Reclamation of Female Intellectual Labor

A persistent thread throughout the essay is the silencing or sidelining of women’s intellectual contributions to theories of child development and parenting. The narrative carefully outlines the stories of several women—Ursula Bowlby, Clare Britton, Alice Winnicott, and Jane Spock—who played significant roles in developing or supporting widely accepted ideas in parenting and child psychology but were often erased from historical accounts.

In each case, these women brought lived experience, creativity, and intellectual insight to work that was ultimately attributed to the men in their lives. The essay questions not only the ethical dimensions of this pattern but its broader cultural implications: by obscuring the female perspective, the scientific establishment shaped maternal ideals without the voices of actual mothers.

The narrator, herself a scholar and mother, is acutely aware of this legacy and how it intersects with her own ambitions and doubts. Her attempt to navigate academia while parenting highlights the ongoing struggle for recognition faced by women in intellectual fields.

This theme becomes a call for historical correction and for the inclusion of maternal voices in shaping the narratives that affect their lives. In recovering these women’s stories, the essay insists on honoring maternal intellect not as supplementary but as central.

The Cultural and Structural Shaping of Motherhood

The essay positions motherhood not as a purely personal experience but as a deeply social and politically shaped role. It critiques the systems and institutions that make maternal self-sacrifice seem inevitable—from the lack of paid parental leave and inadequate childcare infrastructure to the moralistic tone of parenting literature and the myth of the nuclear family.

The narrative contrasts Western ideals of the lone mother with anthropological examples such as Jeanne Altmann’s study of baboons, which illustrates how shared caregiving networks enhance survival and emotional stability. Similarly, Margaret Mead’s life and work offer a counter-model to isolated motherhood, one that includes professional ambition, intellectual community, and cooperative child-rearing.

These examples serve as reminders that maternal norms are not universal but culturally contingent. The narrator’s own life reveals how expectations about maternal sacrifice often collide with structural realities—academic deadlines, daycare logistics, and emotional exhaustion—making the traditional good mother ideal untenable.

By showing how these norms are enforced through both policy and social judgment, the essay advocates for systemic change. It calls for a new cultural framework that understands caregiving as a collective responsibility and recognizes maternal needs as part of—not obstacles to—healthy families and societies.