We Could Be Rats Summary, Characters and Themes

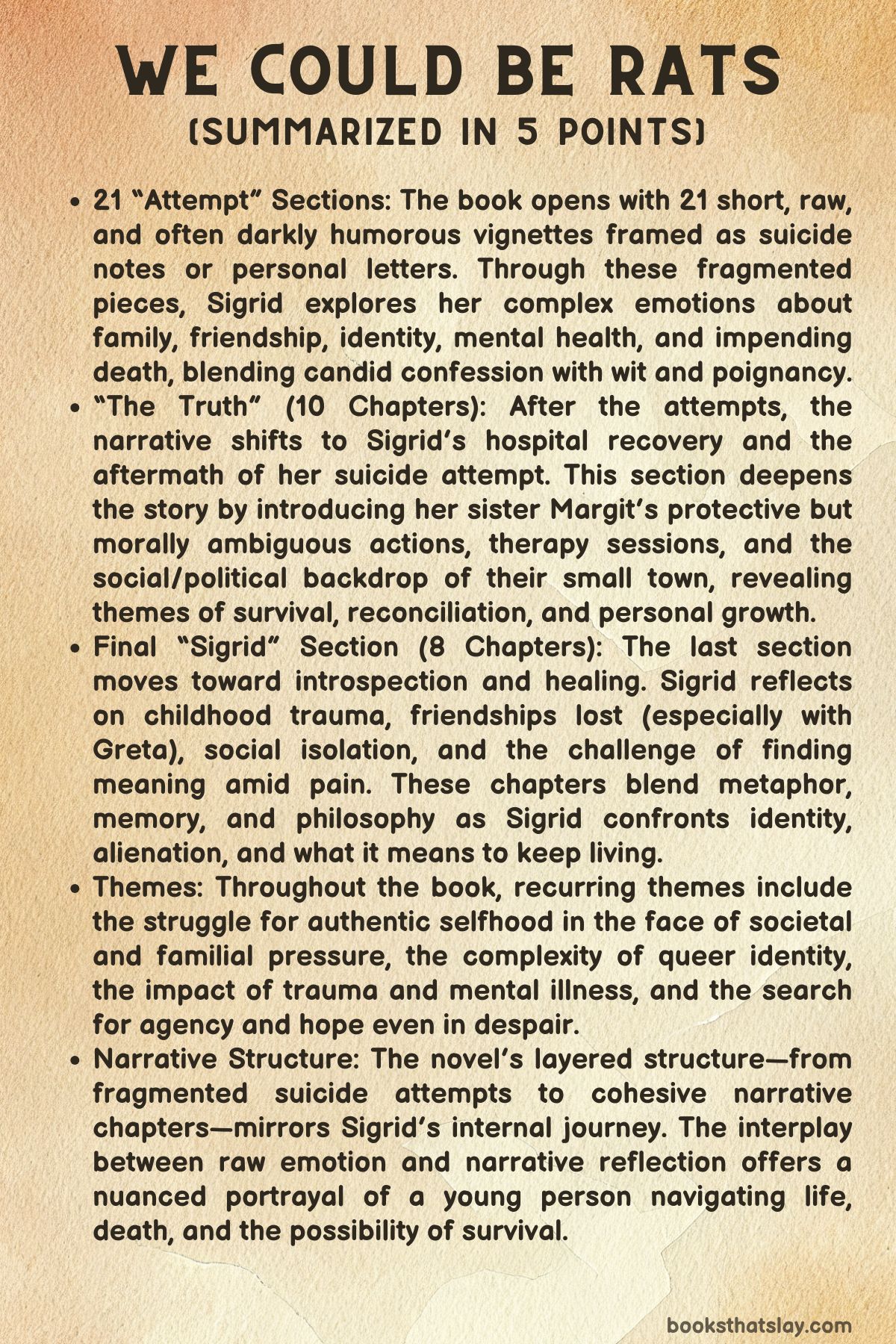

We Could Be Rats by Emily Austin is a profoundly intimate and emotionally charged novel that explores the delicate boundaries between identity, grief, mental illness, and the imaginative inner worlds we create to survive. Told through a mosaic of suicide notes, journal entries, and the fragmented perspectives of two sisters—Sigrid and Margit—the story unearths a quiet, painful desperation buried beneath sarcasm, dark humor, and fantastical imagery.

Set in the conservative and emotionally stifling town of Drysdale, the book centers on Sigrid’s suicide attempt and the aftermath as experienced by both sisters. Through alternating lenses of vulnerability and defiance, the narrative interrogates the roles we inherit, the pain we conceal, and the desperate ways we try to be understood.

Summary

The story begins with the raw, confessional voice of Sigrid, who has crafted a long, evolving suicide note composed of ten different drafts. Each version varies in tone and address, switching between poetic abstraction, emotional confessions, and darkly comedic apologies.

The letter is more than a goodbye—it’s a final attempt to articulate what words have always failed to convey during her life. Sigrid insists that her decision is not rooted in traditional depression or a clinical diagnosis, but in a weariness born of being constantly misunderstood and alienated.

Her emotional struggles are inextricable from her familial relationships, especially with her sister Margit and her emotionally absent parents.

Sigrid’s memories range from idyllic winter scenes and childhood games in the basement to moments of emotional abandonment and confusion. She remembers her toys as companions with rich internal lives, her imagination as a sanctuary where she could be anything—a troll, a rat, a magician.

But growing up forces her to confront the truth: she can’t escape her body, her role, or the societal expectations imposed on her. These limitations, along with the trauma of watching her best friend Greta unravel due to opioid addiction, accumulate into a quiet resignation.

Greta’s public shaming and ultimate disappearance shatter any illusion Sigrid had that life might become bearable. Greta had been her only tether to authenticity and queer companionship; without her, Sigrid feels unbearably alone.

Sigrid’s letter also focuses heavily on Margit, who she sees as her emotional opposite. Margit, the perfectionist, is the one who adapted, absorbed responsibility, and played peacemaker within the volatile family.

While Sigrid fought back through rebellion and fantasy, Margit tried to succeed quietly, often repressing her own pain. Their relationship is marked by love, but also resentment and misunderstanding.

Through her letters, Sigrid pleads for Margit’s empathy and acknowledgment that they both suffered in different ways.

After Sigrid’s suicide attempt, the narrative perspective shifts to Margit, who finds her sister unconscious alongside one final request: to write her goodbye letter. Margit’s world collapses in the sterile hospital room where she waits, oscillating between panic and numbness.

She struggles to understand her sister’s despair, rereads her notes, and reflects on the many moments she missed or misinterpreted. Margit’s narration is erratic and emotionally chaotic.

She forgets simple things, cries over mangoes left by her roommate, and loses her grip on what is real and what is not. She is haunted by what-ifs and consumed by the guilt of not speaking up earlier.

Margit, too, is trapped—by her sense of duty, her loneliness at university, and the societal weight of always appearing “fine. ” Her academic life, once a refuge, becomes unbearable.

She skips classes, finds lectures absurd, and eventually breaks down in front of a professor who encourages her to seek help. Through therapy, Margit begins to understand that grief is not linear and that healing requires vulnerability.

Her sessions with a gentle counselor and doctor offer her a fragile sense of safety and space to be honest.

Margit also begins a tentative relationship with Mo, a classmate who quietly supports her. Their connection is born out of shared moments of sincerity rather than passion.

As they spend time together, Margit opens up about her sister and her past, using their relationship as a fragile tether back to the world. Yet, she remains emotionally overwhelmed, scared of what might happen if she allows herself to hope or trust again.

In parallel, Sigrid’s recovery takes shape through her own therapy sessions and small moments of reflection. She begins practicing techniques like EMDR (eye movement desensitization and reprocessing) to manage her trauma.

However, her road to recovery is uneven. Sigrid still feels the sting of being an outsider, especially in a town that elected Greta’s abuser, Kevin, as mayor.

Sigrid’s act of sending bomb threats to disrupt Kevin’s campaign was a misguided attempt at control—a way to fight back in a world where justice seemed impossible.

Meanwhile, Margit’s sense of helplessness compels her to intervene in the life of Isabelle, a neighbor in an abusive relationship. After hearing screams through the floor, she calls for help and offers Isabelle a way out.

Their brief but meaningful conversation serves as a moment of recognition: two women trapped in pain, surprised to find solace in each other’s company.

Eventually, Sigrid returns home. The sisters spend nights in their childhood bedroom, revisiting the imaginative basement world they once created.

Their reconnection isn’t grand or tidy—it’s quiet, slow, and filled with pauses. The emotional distance between them begins to shrink through shared silences, gentle check-ins, and small gestures of care.

Margit forgives herself, just a little, for not being able to save her sister. She also acknowledges that her love has always been real, even if expressed imperfectly.

The final note of the book is one of quiet endurance. The story doesn’t wrap with a definitive answer, but with Margit lying awake in the dark, her sister breathing beside her, and her parents silently present in the hallway.

Outside, pink clouds hang low in a damp sky—offering not closure, but a sliver of grace. It is a moment suspended between sorrow and survival, suggesting that while pain may never fully leave, neither does the chance for renewal.

Characters

Sigrid

Sigrid, the primary voice of We Could Be Rats, is a profoundly introspective and emotionally fractured young woman whose psychological landscape unfolds through the raw, ever-shifting drafts of her suicide notes. She is not simply a tragic figure but one caught in the crosscurrents of trauma, alienation, creative yearning, and bitter humor.

From the very beginning, Sigrid’s attempt to end her life is portrayed not as a reaction to a single overwhelming tragedy but as the result of accumulated disillusionments, long-standing emotional neglect, and an inability to reconcile the whimsical dream-worlds of her childhood with the cold rigidity of adulthood. Her inner life is rich with metaphor and hallucination—salt shakers that whisper, girls who grow tentacles, elephants at dinner—which points to both her creative brilliance and her fragile grip on reality.

Her family relationships are central to her identity and emotional suffering. Her bond with Margit, her sister, is layered with love, envy, misunderstanding, and mutual pain.

Sigrid envies Margit’s composure and emotional restraint while longing for her recognition and understanding. Her estrangement from her parents stems from a lifetime of emotional inconsistency and perceived dismissal, forcing her to retreat into fantasy and rebellion as coping mechanisms.

Yet despite her sense of isolation, she never loses her capacity for tenderness. She worries deeply about how her suicide will affect others, offering practical suggestions for her funeral and emotional reassurances that underscore her deep empathy even in the face of death.

Sigrid is also a skilled self-mythologizer, constantly shifting narrative perspectives, adopting aliases like “Astrid,” and even fabricating a terminal illness to manage how others perceive her decision. These lies are not manipulations but attempts to exert control over a life in which she feels powerless.

Her pain is intellectual as well as emotional—she analyzes death, societal responses to grief, and the politics of memory with piercing clarity. Her final letters, chaotic yet honest, portray someone who, above all, wanted to be known on her own terms.

Sigrid’s voice is defiant, tragic, humorous, and unforgettable—a testament to a life lived on the margins but never without feeling.

Margit

Margit is the emotional counterbalance to Sigrid’s spiraling psyche, a figure caught between control and collapse, whose journey in We Could Be Rats reveals the often unseen toll of proximity to mental illness and familial trauma. A university student when Sigrid attempts suicide, Margit is suddenly forced to reevaluate her entire sense of self, family, and sisterhood.

Her narrative is saturated with guilt—not only for failing to detect the severity of Sigrid’s anguish but also for harboring secret resentments and for the ways in which she, too, upheld the family’s dysfunctional status quo. Margit is what Sigrid is not: responsible, high-functioning, and socially coherent.

Yet this external stability belies her internal turmoil, which begins to unravel in subtle, heartbreaking ways—she forgets objects, sees meaning in mundane details, and becomes emotionally derailed by small disruptions like a stepped-on mango.

Margit’s journey is deeply introspective, her grief compounded by the responsibility of finding Sigrid, dealing with hospital procedures, confronting her parents’ silence, and attempting to author her sister’s goodbye when asked. Her desperate act of forging Sigrid’s suicide note and destroying incriminating items reveals the fierce, almost primal instinct to protect—even if it means lying.

She becomes the reluctant archivist of their shared history, reading Sigrid’s journals, revisiting childhood haunts, and attempting to piece together a narrative that makes sense of her sister’s pain while reckoning with her own. Her budding romance with Mo offers a brief respite from her emotional isolation, yet she approaches it with the same ambivalence and fragility that characterize her inner life.

Margit also undergoes a tentative healing process, seeking therapy, reconnecting with professors, and slowly reentering the academic and social world she had emotionally abandoned. By the novel’s end, her arc is one of imperfect growth.

She has not solved the mystery of Sigrid’s suffering, nor has she healed completely, but she has embraced the ambiguity of survival and the necessity of presence. Her relationship with Sigrid, though still strained, transforms into one marked by quiet recognition, shared vulnerability, and a willingness to begin again.

Greta

Greta looms over We Could Be Rats like a ghost—an emblem of potential squandered, friendship lost, and innocence corroded. Once Sigrid’s best friend and queer confidante, Greta represents a vital part of Sigrid’s identity and adolescence.

Their bond was forged through mutual rebellion and imagination, but Greta’s descent into opioid addiction, public disgrace, and eventual disappearance fractures something irreparably within Sigrid. Greta becomes the most visceral symbol of societal failure: a girl abused, ostracized, and ultimately discarded by a community more eager to preserve appearances than protect its most vulnerable members.

Sigrid’s guilt over Greta’s downfall is heavy—she was the first to experiment with OxyContin, and her retreat from Greta’s life was as much self-preservation as it was cowardice. Greta’s mugshot, her increasingly erratic behavior, and the community’s cruel judgment underscore the brutal realities of addiction and social abandonment.

But Greta is also a mirror: her fate serves as a warning and a reflection of what could—and nearly did—become of Sigrid herself. Her presence in Sigrid’s hallucinations and letters reveals an unhealed wound, one that festers beneath all of Sigrid’s emotional implosions.

Even in her absence, Greta remains one of the most potent emotional forces in the novel, embodying both a personal tragedy and a scathing critique of a culture that punishes the wounded instead of helping them heal.

Mo

Mo offers a breath of emotional stability in the whirlwind of Margit’s unraveling, a calm and quietly affectionate presence who neither demands nor judges. He first enters Margit’s life at a moment of intense emotional disorientation, and though their connection begins almost accidentally, it gradually evolves into something more sincere and grounding.

Mo is not a savior figure, but rather a compassionate peer who sees Margit clearly and offers her space to speak, grieve, and falter without fear of rejection. His consistent kindness, willingness to listen, and emotional attunement make him a stabilizing force in Margit’s otherwise chaotic world.

What distinguishes Mo is his patience—he does not try to fix Margit or interpret her pain but simply remains present. This presence becomes crucial in Margit’s tentative steps toward recovery.

Their drive through Drysdale, their shared silences, and his gentle responses to her emotional overwhelm all signify a kind of understated intimacy. Mo is a rare source of non-traumatic connection in a story riddled with loss and dysfunction.

His role, though not dominant, is deeply significant in symbolizing the possibility of healthy relational dynamics. Through Mo, Margit glimpses a different kind of life—not one devoid of pain, but one where pain does not eclipse connection.

Isabelle

Isabelle, though a more peripheral character in We Could Be Rats, functions as a powerful parallel to both Sigrid and Margit. She is Margit’s downstairs neighbor, a woman trapped in an abusive relationship, whose screams through the ceiling prompt Margit into action.

Isabelle’s inclusion in the narrative is brief but weighty—she embodies the invisible suffering that often persists in plain sight, mirroring the emotional and psychological abuse Sigrid endured within her own family. When Margit intervenes and offers Isabelle a means of escape, their ensuing conversation reveals a mutual recognition of pain and resilience.

Isabelle’s gratitude and vulnerability open up a space where Margit can extend care, perhaps as a form of redemption for all the times she couldn’t save Sigrid.

Isabelle also reminds Margit—and the reader—that violence and despair take many forms, and that courage doesn’t always look like healing; sometimes it looks like leaving. Her quiet departure from the apartment and the tender moment they share highlight the power of solidarity among women who have suffered, even when they barely know one another.

Isabelle’s brief appearance leaves a lasting impression, reinforcing the novel’s themes of invisible struggle, communal empathy, and the transformative potential of being witnessed.

Themes

Alienation and the Failure of Belonging

From the very first iterations of Sigrid’s suicide note in We Could Be Rats, it becomes evident that her decision is not rooted in conventional depression, but in a chronic inability to feel like she belongs—anywhere or to anyone. She is acutely aware of her difference, of how her emotional intensity and neurodivergent inner life alienate her from a world that demands seamless conformity.

Her alienation isn’t dramatic; it’s quiet, constant, and exhausting. Rather than framing her death as a tragic loss of potential, Sigrid positions it as a rational retreat from an environment that neither saw nor accommodated who she was.

Even in moments of joy or rebellion—graffitiing, swimming in strangers’ pools—there’s a background hum of estrangement. These acts are less about seeking belonging and more about confirming her separateness.

Margit, her sister, acts as a kind of mirror: someone who learned to belong by playing the role expected of her. Sigrid never learned to do that and paid the psychological price.

Her withdrawal is thus not an implosion, but a farewell to a world she never truly felt part of.

The Inheritance and Burden of Family

The complexity of Sigrid and Margit’s relationship is central to the emotional weight of the story, and their family dynamic is riddled with pain, misunderstanding, and unsaid love. The parents, portrayed as both volatile and emotionally unavailable, establish a home where emotional expression is either punished or ignored.

Childhood moments of connection—painting, playing with toys, skating—are continually interrupted by shouting, silence, or outright neglect. Both sisters develop opposing coping mechanisms: Margit becomes perfectionist and functional, while Sigrid veers toward defiance and fantasy.

Yet, despite their differences, they are bound by shared trauma and unspoken affection. The parental support of Kevin, Greta’s assaulter turned mayor, is another rupture—symbolizing the family’s inability to stand on the side of justice or empathy.

Margit carries guilt for not seeing Sigrid’s pain, while Sigrid shoulders resentment for the attention Margit received for being “the good one. ” Their reconciliation, though small and uncertain, is powerful because it acknowledges the complexity of family as a site of both injury and longing.

The Politics of Mental Health and Suicide

One of the most radical aspects of We Could Be Rats is its unflinching critique of how society interprets and responds to suicide. Sigrid repeatedly insists she is not mentally ill in the conventional sense, a statement that feels provocative because it demands a broader understanding of suffering.

Her pain is contextual: systemic, familial, social—not purely internal or pathological. She is not asking for pity, nor offering a sanitized version of her pain; she is asking to be taken seriously on her own terms.

The drafts of her suicide note vary in tone, but all circle around the question of how society narrativizes death—especially the death of a queer, sensitive young woman who refuses easy explanations. In this way, the book becomes not just a fictional letter but a meta-commentary on death etiquette, how we mourn, and who gets to be mourned.

It also challenges readers to consider what it means to respect the autonomy of someone who articulates their suffering so clearly. The note isn’t a cry for help—it’s a complex assertion of agency, shaped by years of emotional labor that never found a landing place.

The Erosion of Fantasy and the Pain of Growing Up

Throughout Sigrid’s letters, and echoed in Margit’s reflections, is the loss of imaginative possibility that once made life bearable. Childhood is remembered as a time when being a goblin, shark, or unicorn was not only possible but sustaining.

These fantasies weren’t escapes from reality—they were alternatives to a reality that never felt safe. As she ages, Sigrid becomes aware that the world will not accommodate those magical selves.

She cannot be the troll in the basement, or the elf who repairs shoes at night. Instead, she becomes someone who pretends to be someone else—Astrid, the girl with a terminal illness—just to maintain some semblance of control.

This loss of fantasy is not merely nostalgia; it is grief for versions of herself that were discarded in the transition to adulthood. The hallucinations—salt shakers that whisper, songs that feel like they belong to someone else—are not just signs of mental collapse but remnants of a once-vivid internal world now breaking down.

The novel suggests that part of growing up, in a culture that doesn’t honor complexity or vulnerability, is a slow death of wonder.

Grief, Guilt, and the Burden of Survival

Both Sigrid and Margit are haunted by Greta, the friend whose descent into addiction becomes a symbol of every failed hope and unresolved guilt. Sigrid sees herself as partially responsible—she introduced Greta to OxyContin—and never forgives herself, especially after seeing Greta’s mugshot and the town’s cruel response.

Greta’s downfall is also symbolic of what happens to those who can’t or won’t perform normative success. In watching Greta’s decline, Sigrid sees a mirror image of her own feared trajectory.

For Margit, the guilt is more diffuse: she regrets not acting sooner, not saying the right thing, not being kinder. The story treats guilt as a condition of being alive in a broken system.

It’s not just guilt for individual actions but for complicity, silence, misunderstanding. Survival becomes a kind of burden—one that neither sister knows how to carry.

The tragedy is not only Greta’s overdose or Sigrid’s suicide attempt, but the unrelenting question of what it means to continue living when healing seems distant and memory is saturated with regret.

Queerness, Shame, and Performance

The narrator’s queerness, though never sensationalized, is deeply woven into her experiences of shame and identity. Her relationships—with Greta, with her short-term girlfriend, with herself—are all shaped by a need to perform stability, humor, or mystery to avoid exposure.

She creates personas, lies about illnesses, and invents identities not to manipulate, but to survive. In Drysdale, queerness is stigmatized, ignored, or exploited.

Greta’s queerness, in particular, is weaponized against her after her assault, and her erasure from public empathy is a chilling reminder of how quickly marginalized people are discarded. For Sigrid, queerness is not only sexual orientation—it’s a framework for understanding how she feels always slightly out of phase with others.

She wants to be seen but fears what visibility might cost. Her suicide note is thus also a queer document: a final attempt to tell the truth in a world that demands silence.

Even the recurring motif of rats at a carnival speaks to queerness—creatures misjudged, clever, and marginalized, but full of their own strange joy.

Hope as a Fragile Act of Presence

By the end of We Could Be Rats, neither sister is healed, but both are still here. The presence of Margit beside Sigrid in their childhood bedroom, the quiet act of praying in the dark, the shared memories of toys and stories—all suggest that hope doesn’t arrive as revelation, but as a decision to stay present.

Margit starts talking to professors and therapists, Sigrid continues therapy, and both begin rebuilding not by erasing the past, but by holding it alongside the present. There is no grand transformation or epiphany, only tentative steps toward connection.

This fragility is the story’s greatest strength: it understands that some lives are too complex for closure, but still worthy of continuity. The final image—pink clouds in a damp sky—captures this beautifully.

It’s not a metaphor for healing, but a fleeting beauty noticed even in pain. In a world that offers few guarantees, presence itself becomes an act of resistance.