What The Light Touches Summary, Characters and Themes

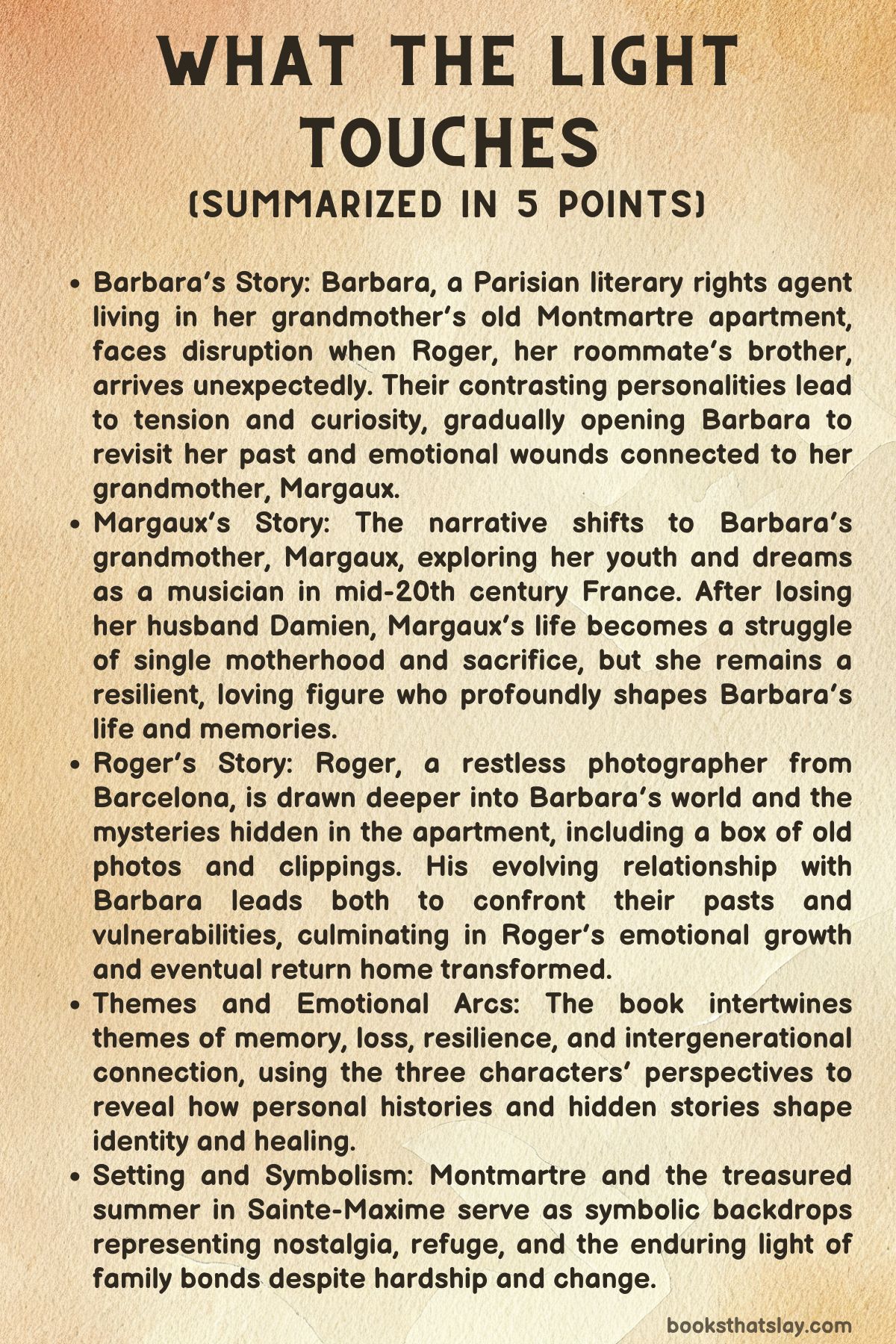

What the Light Touches by Xavier Bosch is a multilayered novel exploring how memory, family legacy, and hidden histories shape identity across generations. Set against the vibrant backdrop of Montmartre and the haunting echoes of Nazi-occupied Paris, the story unfolds through the intersecting lives of Barbara Hébrard, a reserved literary agent guarding emotional distance, and Roger Narbona, a curious Spanish photographer searching for direction.

When fate thrusts them into shared quarters, a journey begins—one that will unravel wartime secrets, reframe love and trust, and give voice to buried stories of courage and contradiction. This is a quiet but powerful novel about how remembrance can lead to redemption.

Summary

Barbara Hébrard leads a life of control and solitude in a Montmartre apartment once owned by her grandmother, Margaux. Her world shifts unexpectedly when she comes home one Saturday to find a stranger, Roger Narbona, asleep on her couch.

He is the brother of her roommate Marcel, who had failed to notify Barbara of the arrangement. Roger’s easygoing nature and spontaneous presence contrast sharply with Barbara’s precision and defensiveness, creating an immediate tension between them.

Roger’s arrival is the catalyst for unearthing long-buried emotional truths. Though Barbara appears self-sufficient and rigid, the apartment’s sparse, impersonal decor hides a deeper story.

She inherited the place from her grandmother, Mamie Margaux, who now lives in a retirement home. Margaux had removed all photographs of herself, an act that Barbara accepted without question.

This mystery leads Roger to probe further, disturbing the careful emotional order Barbara has constructed.

Barbara reminisces about a transformative summer in 1975 when, as a child, her grandmother rescued her from a household overshadowed by her mother’s deep depression. They escaped to Sainte-Maxime, where Margaux nurtured Barbara with a mix of discipline, freedom, and unconditional love.

That summer became foundational to Barbara’s understanding of affection, trust, and safety.

Now in her early forties, Barbara works in publishing, selling international rights for French authors. Her career offers stability after a painful divorce from Maurice, a betrayal that left her wary of intimacy.

Paris represents not adventure but survival—an escape from her old life. Meanwhile, Roger, mourning his father and burnt out from a career in photojournalism, has come to Paris hoping to reclaim his creative vision through photographing beauty rather than war and tragedy.

While adjusting to their uneasy cohabitation, Roger discovers a tin box hidden beneath the bed containing old photographs. The images spark his curiosity about Margaux’s life and the apartment’s hidden stories.

But the tension between him and Barbara escalates after a disagreement over a missed delivery. Their argument reveals mutual emotional fragility: Barbara’s longing for control stems from abandonment and grief, while Roger struggles with aimlessness and a need for connection.

Despite their friction, the shared space forces them to observe and eventually understand each other. Their emotional walls begin to crack, helped along by conversations about memory, loss, and art.

Barbara regularly visits her grandmother at the Viviani Retirement Home, where their routine is filled with sweets, hand cream, and quiet rituals. Their bond remains strong, but a visit to a photography exhibit destabilizes Barbara’s trust in the past.

At the Bibliothèque historique de la Ville de Paris, Barbara sees a photo taken during the Nazi occupation. It shows a young woman on a bicycle—clearly her grandmother.

The photo, captured by André Zucca, a known propaganda photographer, complicates the narrative Margaux had told of wartime resistance. This discovery plants seeds of doubt in Barbara, raising questions about complicity and truth.

She doesn’t confront Margaux immediately, instead listening once again to stories of love and survival, waiting for meaning to surface.

Barbara and Roger’s growing closeness is interrupted when a woman named Laurence, a waitress from a local bistro, is found in their apartment—first in the shower, then again in Barbara’s bathroom, completely naked. The invasions of space unearth deep-seated trauma for Barbara, echoing her discovery of her husband’s affair.

Roger’s apologies and attempts to reconcile reveal his genuine concern, but trust has been shaken.

Their emotional dynamic shifts again when Roger delivers a photograph of the same wartime image to Margaux, prompting her to open up about her past. This leads to a story within the story: the tale of Margaux as a young girl during the occupation and her relationship with her oboe teacher, Damien.

What begins as structured music lessons gradually evolves into a deep emotional connection between them, defying the bleakness of the era. Their affection builds in secrecy—quiet hand-holding at the cinema, a first kiss, a mutual escape into music.

But the reality of the war is never far behind. When a fellow musician is arrested and tortured by the Nazis, Damien fears for his safety.

He writes a love letter to Margaux and entrusts it to her father for safekeeping. This emotional record becomes part of Margaux’s legacy, hidden for decades.

Later, Roger discovers an unpublished manuscript in Jasper’s apartment—Barbara’s great-uncle and Margaux’s lifelong confidant. The manuscript, once hidden away, reveals in detail Margaux’s personal account of Nazi-occupied Paris.

Roger shares its contents with Margaux, triggering her decision to tell the full story of a mission in the 1960s. She and Jasper tracked down Zucca, who had reinvented himself as a wedding photographer.

Their confrontation is heavy with moral reckoning. Margaux challenges Zucca’s claim of innocence, accusing him of using photography to distort reality and hide suffering.

The encounter ends with Margaux writing a personal reflection that speaks to regret, aging, and the importance of confronting one’s past.

In parallel, Barbara continues to navigate her professional and emotional life. She secures an important rights deal with a Norwegian editor and flirts cautiously with the idea of romance.

Yet her return to the apartment after learning of Jasper’s death deepens her bond with Roger. Margaux, moved by Jasper’s passing, shares her final story with Barbara—the journey to confront Zucca.

Her storytelling is her legacy: a method of transmitting not just facts but feelings, contradictions, and moral clarity.

The novel ends with Roger’s art exhibit titled “The Bicycle Woman. ” His photographs of Margaux—raw, graceful, dignified—transform public perception.

No longer just a figure in a propaganda image, she becomes a symbol of survival and truth. Barbara, witnessing the emotional impact of the exhibit, understands her grandmother anew.

In the final scene, she and Margaux dance together. The gesture is symbolic, a merging of generations, and a celebration of memory and transformation.

Through this act, Barbara lets go of certainty and embraces the complexity of her inheritance, beginning to see that the light touching her life is not always easy or clean—but it is real.

Characters

Barbara Hébrard

Barbara Hébrard is a woman shaped by control, solitude, and a legacy of quiet resilience. At forty-one, she lives a carefully ordered life in her grandmother’s old Montmartre apartment, which she keeps devoid of personal artifacts, as if attempting to seal away any emotional trace of her past.

Her composure masks deep wounds—grief over her parents’ deaths, betrayal from a failed marriage, and questions about her grandmother’s secret history during the Nazi occupation. Barbara is both fiercely independent and profoundly lonely.

She works remotely as a foreign rights agent with passionate dedication, particularly toward female authors she champions with conviction. Her interactions with Roger, her unexpected roommate, begin with irritation and suspicion, revealing her territorial nature and discomfort with vulnerability.

Yet, over time, their shared experiences—particularly the discovery of a photograph implicating her grandmother in wartime propaganda—crack open Barbara’s emotional barriers. She gradually allows herself to confront uncertainty, doubt, and buried emotions.

Her protective shell begins to soften, even as her fear of betrayal resurfaces when she finds Laurence in her apartment. Barbara’s journey in What the Light Touches is one of internal transformation: from isolation and control to a tentative acceptance of love, ambiguity, and legacy.

Roger Narbona

Roger Narbona enters the narrative as a disrupter of Barbara’s life but evolves into a catalyst for emotional revelation and historical reckoning. A former photojournalist from Barcelona, Roger is recovering from the trauma of his father’s death and his disillusionment with the profession he once loved.

Drawn to beauty over tragedy, he now seeks solace in capturing aged charm and personal stories through his lens. His casual demeanor and unfiltered curiosity initially clash with Barbara’s rigidity, but his presence becomes a quiet force that challenges her emotional barricades.

Roger is impulsive, sometimes insensitive, but always sincere. His discovery of Margaux’s photograph and subsequent investigation into her past demonstrate his journalistic instinct and personal investment in truth.

He is not just a passive observer but an active participant in unraveling the past. His emotional depth surfaces in his desire to reconcile with Barbara, in his reverence for Margaux, and in his culminating exhibition that honors her with dignity and truth.

Roger’s character in What the Light Touches embodies the search for authenticity—both in art and in human connection—and his journey reflects a delicate balancing act between remembrance and renewal.

Margaux Dutronc (Mamie Margaux)

Margaux Dutronc, or Mamie Margaux, is the magnetic, mysterious matriarch whose legacy threads through every layer of the narrative. In her youth, she is vivacious, brave, and artistically curious—a young woman whose oboe lessons with Damien during the Nazi occupation blossom into a tender, transformative romance.

This clandestine relationship, steeped in music and defiance, becomes emblematic of her courage and sensitivity. As an old woman in a retirement home, she remains witty and wise, often indulging in rituals with Barbara, such as sharing sweets and hand cream, which reflect her enduring warmth.

However, Margaux is also elusive. Her refusal to be photographed and the discovery of her image in a propaganda exhibit suggest a deeper past, entangled with moral complexity.

Her confrontation with André Zucca, decades later, reveals her fierce sense of justice and her refusal to let propaganda define her or Paris. Even in her advanced age, Margaux seeks to control her story—writing letters as veiled reflections on aging and mortality.

In What the Light Touches, she represents the power of memory, the ambiguity of legacy, and the resilience of women who carry history within them.

Damien

Damien is a figure of quiet strength, artistic mentorship, and emotional restraint. A music teacher during the Nazi occupation, he becomes Margaux’s oboe instructor, and their lessons soon evolve into a space of intimacy and resistance.

He embodies patience and passion, using music not just as a technical discipline but as an emotional refuge. His guidance is both paternal and romantic, grounded in a deep belief in the redemptive power of art.

Damien’s affection for Margaux grows with every session, expressed subtly through gestures, metaphors, and eventually, through music. The war looms over their bond, especially when a fellow musician is tortured for resistance activity.

Damien, aware of the danger, writes Margaux a farewell letter filled with admiration and love—a document of heartbreak and devotion. His character, though largely present in the past, is pivotal in shaping Margaux’s emotional and political consciousness.

Damien in What the Light Touches serves as a symbol of art’s defiance, the tenderness possible even in tyranny, and the deep imprint of first love.

Jasper

Jasper is a peripheral yet essential figure in the story’s quest for truth. A friend and partner in Margaux’s postwar journey, he becomes her ally in tracking down Zucca in the 1960s.

Jasper’s chaotic apartment and bachelor lifestyle contrast with his pivotal role as the keeper of Margaux’s manuscript—the key to her wartime story. Though he is largely offstage, his death prompts Margaux and Barbara to confront what remains unsaid and unrecorded.

Jasper’s presence in What the Light Touches is that of a loyal witness and guardian of history, someone who understands the importance of narrative, memory, and delayed revelations.

Laurence

Laurence serves as both a literal and symbolic interruption in Barbara’s life. A waitress from a local bistro and briefly entangled with Roger, her presence in the apartment—especially her appearance in the shower and later fully nude in Barbara’s bathroom—triggers Barbara’s most visceral emotional responses.

For Barbara, Laurence is not merely a rival or guest but a painful echo of betrayal, reminiscent of the moment she discovered her husband’s affair. Though Laurence herself is not malicious, her role magnifies Barbara’s fragility, her fear of loss, and her need for control.

Laurence, in What the Light Touches, becomes a mirror to Barbara’s unresolved trauma and a test of her ability to forgive, adapt, and move forward.

Maurice

Maurice, Barbara’s ex-husband, is a shadowy but impactful presence in her emotional landscape. Though he never appears directly in the narrative, his betrayal—presumably through infidelity—has deeply scarred Barbara, prompting her move to Paris and fueling her emotional detachment.

Maurice represents the collapse of Barbara’s former life and the fragility of trust. His legacy lingers in Barbara’s guarded demeanor, her reluctance to allow intimacy, and her hyperawareness of intrusion.

In What the Light Touches, Maurice is a specter of heartbreak, emblematic of past wounds that continue to shape present choices.

Frode Arnesen

Frode Arnesen, the Norwegian editor with whom Barbara negotiates a rights deal, is a minor character who highlights Barbara’s professional prowess and inner conflict. Their flirtatious dinner, set against the backdrop of literary negotiation, underscores her ability to command space and charm when needed.

Frode serves as a foil to Roger—refined, cosmopolitan, and less emotionally entangled. Yet, Barbara’s emotional distance in this interaction shows that despite her flirtation, she remains guarded.

Frode’s role in What the Light Touches is that of a passing temptation, a symbol of the life Barbara might have had if she chose ambition over emotional vulnerability.

Themes

Memory and the Burden of the Past

In What the Light Touches, memory is not a passive repository of past events but an active force that shapes identities, defines relationships, and often complicates present choices. The narrative reveals that memory can be both cherished and corrosive, often preserving moments of beauty alongside shadows of unresolved trauma.

Barbara’s relationship with her grandmother Mamie Margaux is steeped in fond memories of summers spent away from parental grief, moments that taught her joy, strength, and survival. These recollections construct Barbara’s notion of familial love and inform her guarded disposition in adulthood.

However, memory also becomes a site of conflict when a photograph taken during the Nazi occupation reveals a version of Margaux that Barbara had never imagined. The image, captured by a known propagandist, threatens to shatter the idealized memory Barbara holds of her grandmother and raises questions about complicity, silence, and survival during wartime.

Similarly, Roger’s discovery of the photograph and later the manuscript detailing Margaux’s covert confrontation with André Zucca forces both him and Barbara to re-evaluate how the past has been remembered—and forgotten—within their family. These acts of remembrance are emotionally taxing; they blur lines between truth and fiction, guilt and innocence.

As the characters grapple with these revelations, the novel exposes the unsettling reality that memory is often curated, incomplete, or distorted, whether for self-preservation or protection of others. Ultimately, the book suggests that coming to terms with memory requires not only confronting painful truths but also choosing what kind of legacy one wishes to carry forward.

Generational Legacy and Inheritance

The novel’s emotional terrain is anchored in the idea that the past, especially familial history, is not something one merely recalls but rather inherits—sometimes with reverence, sometimes with suspicion. Barbara inherits her grandmother’s Montmartre apartment, but far more enduring is the emotional and moral legacy passed down from Mamie Margaux.

This legacy is not static; it is an evolving set of values, stories, and silences that Barbara must interpret, accept, or resist. The apartment itself is a physical representation of Margaux’s influence—filled with traces of her presence yet notably devoid of personal photographs, signaling intentional omissions.

As Barbara unearths hidden elements of her grandmother’s life—from the wartime photograph to the final confession about confronting Zucca—she becomes the reluctant custodian of a history that is both honorable and morally ambiguous. The transmission of legacy is not limited to Barbara alone; Roger, too, inherits a sense of responsibility when he discovers and later exhibits Margaux’s story through photography.

His exhibit, “The Bicycle Woman,” reframes Margaux’s past not as propaganda but as testimony, passing on to the public a version of history that demands reflection. Legacy, in this novel, is a mosaic of the spoken and unspoken, the remembered and the hidden, and inheriting it requires a reckoning with its contradictions.

The characters are not simply carriers of genetic lineage—they are interpreters, editors, and sometimes challengers of the stories they are given. The novel ultimately argues that inheritance is a moral act: one must decide which truths to preserve and which myths to dismantle.

Love, Trust, and Emotional Vulnerability

Emotional vulnerability in What the Light Touches is portrayed as a risk and a necessity, especially in the realm of romantic and familial love. Barbara’s journey is one of carefully guarded detachment—her past betrayal by Maurice and the emotional exhaustion that followed have left her skeptical of intimacy.

Her initial hostility toward Roger is fueled not just by the violation of her personal space, but by a fear of losing control over the compartments she has built to safeguard herself. Roger’s laid-back and intrusive presence serves as both a disruption and a catalyst, gradually inviting Barbara to examine the cost of her emotional isolation.

Their evolving relationship is punctuated by moments of tension and temporary reconciliation, often surfacing unhealed wounds rather than resolving them. When Laurence appears in their shared apartment, Barbara’s visceral reaction exposes how deeply past betrayals continue to shape her present responses.

Vulnerability, in this context, is not romanticized but treated as something messy, risky, and often humiliating. Yet, the slow thaw between Barbara and Roger, culminating in shared experiences like the literary party and the emotional aftermath of Laurence’s intrusion, hints at the possibility that connection—even if imperfect—is worth pursuing.

Love in this narrative is not redemptive in a simplistic way; it is bound up with grief, suspicion, and the need for mutual recognition. By showing how intimacy requires both the courage to confront one’s fears and the willingness to embrace another’s flawed humanity, the novel underscores that emotional openness is less about grand gestures and more about everyday acts of trust.

Identity, Secrecy, and the Complexity of Truth

Throughout the novel, identity emerges as a multifaceted and contested domain, shaped not only by who one is, but by what one conceals, reveals, or chooses to forget. Barbara’s sense of self is constructed through discipline, professional success, and a refusal to engage with emotional vulnerability.

She presents a curated version of herself to the world—composed, aloof, and emotionally self-sufficient. Yet this identity begins to unravel in the presence of Roger and through the unsettling revelations about her grandmother.

Similarly, Mamie Margaux’s identity is fractured across timelines. To young Barbara, she was a source of warmth and strength; to wartime Paris, she may have been a figure of propaganda, willingly or not; to herself, she is someone who carries the weight of unspoken choices and long-guarded secrets.

The Zucca photograph becomes emblematic of how identities can be manipulated, misrepresented, or stripped of context. When Margaux confronts Zucca, she challenges not just his moral choices, but the broader question of who controls narrative and meaning.

The novel reveals that truth is often not singular—it is refracted through memory, perspective, and motive. Barbara’s own crisis stems not from discovering a lie, but from realizing how much she did not know.

As the characters wrestle with identity—be it personal, historical, or relational—the novel suggests that truth is not a possession but a pursuit. One must be willing to live with ambiguity, to ask difficult questions, and to accept that some answers may remain forever unresolved.

Art as Resistance and Witness

Art in What the Light Touches is more than an aesthetic expression; it functions as a tool of resistance, remembrance, and testimony. Whether it is Damien teaching Margaux to express emotion through the oboe, or Roger curating an exhibition that reclaims her narrative, artistic creation becomes a form of ethical engagement with history and selfhood.

Music, in the context of Margaux’s wartime adolescence, is both a sanctuary and a subversive act. Her lessons with Damien offer not just emotional refuge but also a quiet defiance against the brutalities of occupation.

Their shared artistry builds a private world where beauty and humanity are preserved amid external collapse. Photography, conversely, plays a dual role in the narrative: as a medium of distortion when used by André Zucca, and as a medium of reclamation when used by Roger.

Zucca’s photographs romanticize life under Nazi rule, erasing suffering and sanitizing oppression. In contrast, Roger’s portraits of Margaux aim to restore complexity and truth, capturing her with the dignity of someone who has lived, suffered, and remembered.

Through his exhibit, he repositions her from subject to storyteller, from a misrepresented image to an agent of history. The novel emphasizes that art carries ethical weight—it can obscure or illuminate, exploit or honor.

By choosing to create and share stories that are emotionally and morally honest, the characters engage in a form of quiet resistance against the erasures of time and the simplifications of memory. Art, thus, becomes not only a mirror of experience but a means of survival and redefinition.