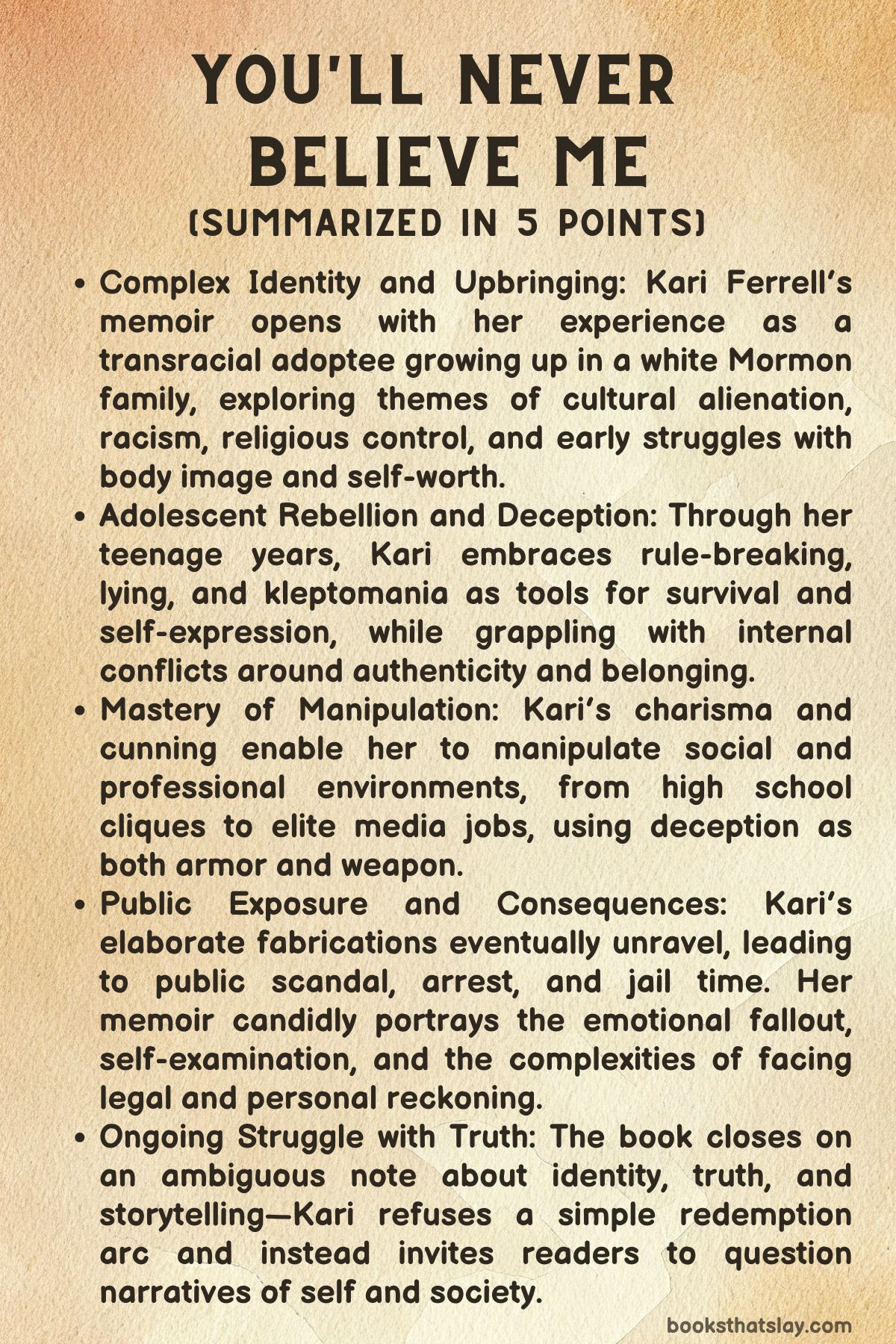

You’ll Never Believe Me Summary, Analysis and Themes

You’ll Never Believe Me by Kari Ferrell is an audacious memoir that combines razor-sharp humor with raw emotional honesty to chart the chaotic and often shocking life of its author. Raised in a white Mormon household as a Korean adoptee, Ferrell confronts cultural dislocation, racial marginalization, body image insecurities, and queerness within a repressive religious environment.

Her narrative unspools from precocious childhood observations to full-blown cons, stints in jail, and ultimately, a search for healing and purpose. Equal parts confessional, critique, and comeback, this memoir is a portrait of a woman who refuses to be either villain or victim, instead embracing her contradictions to forge a complicated path toward redemption.

Summary

You’ll Never Believe Me begins on a playground, where a young Kari Ferrell learns that language can be both a weapon and a shield. Adopted from South Korea by white American parents, Kari is raised in a world that constantly reminds her she is different.

Despite her parents’ love, her racial identity and cultural isolation set her apart in their overwhelmingly white community. At school, she is ridiculed for her appearance and foreignness, an experience that propels her into early performances of sarcasm, sharp wit, and misdirection—tools she would sharpen with age.

A show-and-tell presentation featuring her “Legal Resident Alien” card earns laughs but also reveals the xenophobia lurking in even the most innocent contexts.

Her family, well-intentioned but culturally unequipped, encourages assimilation. They raise her with consumerist comforts and religious devotion, eventually converting to Mormonism.

The church gives Kari structure and a sense of belonging, but it also brings suffocating rules, racism, and homophobia. From bizarre rituals like baptisms for the dead to terrifying interviews where she is made to confess her private thoughts, Mormonism becomes a space of indoctrination rather than faith.

Her emerging queer identity further complicates her relationship with the church, breeding guilt and secrecy.

As Kari matures, her body becomes another battlefield. A humiliating experience at a restaurant that charges based on weight marks the beginning of a lifelong tension with food and body image.

Simultaneously, she learns that beauty and appearance can be leveraged for power, even as they are used against her. These dual messages—shame and empowerment—fuel a volatile relationship with control and consumption.

By her teen years, Kari is defiant. She skips school, shoplifts, and surrounds herself with fellow outcasts.

Her politics become radical, and her friendships intense, sometimes dangerous. A heated conflict over a stolen phone nearly results in a shooting, signaling how high the stakes have become.

Desperate for connection, Kari often crosses lines, craving validation even as she sabotages the very relationships she seeks.

The chapter “Baby’s First Grift” traces her move from rebellious teen to seasoned con artist. At seventeen, she orchestrates a relocation to Salt Lake City to be near a boy named Charlie.

She deceives him and others with fake jobs and false charm. Her scams begin small—writing a bad check to Charlie—but escalate into a full-scale fraud operation, using forged checks and manipulations that turn Charlie into an unwitting accomplice.

Jail offers a dark comedic lens through which Kari examines the dehumanization of incarceration. Yet, rather than remorse, she finds twisted empowerment in owning her grifter persona.

After release, Kari doubles down. She scams strangers, manipulates friends, and eventually reinvents herself in New York with a job at VICE, secured through a fabricated résumé.

Her past catches up when her mugshot is exposed online, and she flees to Brooklyn under a fake name. Her arrest in Philadelphia marks a turning point, captured not in desperation but in quiet relief.

The story deepens during her incarceration in Riverside Correctional Facility. Kari bonds with Spades, a gender-fluid inmate who becomes a source of strength.

A riot erupts when Spades retaliates against a guard for throwing away perfume ads connected to their late mother. Kari, though fearful, sides with Spades, finding a strange form of solidarity in rebellion.

Afterward, life behind bars becomes oddly vibrant. Kari adapts, invents beauty routines, navigates inmate politics, and becomes a figure of both infamy and admiration.

She is extradited to Utah, where the legal process reignites questions about her identity. ICE involvement reminds her that her American identity, already fragile, is conditional.

In jail, she connects with other women—like Madyson, a heroin addict, and Haylee, a pregnant former peer—whose lives reflect systemic neglect. Kari sees brilliance, humor, and resilience in these women, realizing that incarceration often punishes trauma rather than healing it.

After her release, Kari returns to instability. She moves into the Kurt Hotel, a halfway residence overseen by a shady manager named Gareth.

Suspicious behavior—including surveillance and secret money stashes—escalates her paranoia. Amid the chaos, she grows closer to Elliot, a government contractor whose trauma parallels her own.

Their relationship, built on unlikely trust, becomes a rare anchor in her life.

Probation transferred, Kari returns to New York to rebuild. She finds work, gets married, and begins writing again, but fear of exposure looms.

When a past employer uncovers her history, she’s fired, triggering a spiral. Therapy becomes a crucial part of her recovery, and through it, she discovers the Korean concept of han—a cultural framework for grief, anger, and resilience.

A trip to South Korea deepens her understanding of self and heritage. There, in landscapes rebuilt from destruction, she sees her own capacity for renewal.

Back in America, she is reminded of her liminal identity—neither fully Korean nor fully American. She begins advocating for incarcerated people, especially LGBTQIA+ individuals, reframing her past as a source of power.

Kari no longer hides her story. Instead, she channels it into storytelling through a new production company, Without Wax Productions, which centers voices of women of color and the formerly incarcerated.

In the end, You’ll Never Believe Me resists easy moral resolution. Kari doesn’t ask for absolution, nor does she paint herself as entirely reformed.

The memoir is an act of reclamation—a narrative in which the author asserts her right to define herself. Through shame, audacity, survival, and truth-telling, Kari Ferrell emerges not as a cautionary tale, but as a complex, evolving person determined to keep rewriting her story on her own terms.

Key People

Kari Ferrell

At the heart of Youll Never Believe Me lies Kari Ferrell, whose life story functions as both narrator and central force around which the memoir’s emotional gravity spins. Kari is portrayed as a fiercely intelligent, quick-witted, and deeply complex individual—one who oscillates between victimhood and culpability, humor and sorrow, illusion and raw truth.

Her childhood is marked by a profound sense of alienation, having been adopted from South Korea into a white American Mormon household. This early dislocation fuels her lifelong preoccupation with identity, belonging, and survival.

As a young girl, Kari becomes acutely aware of her racial difference and deploys language as both a shield and a weapon, navigating a world that exoticizes and rejects her simultaneously. The trauma of cultural dissonance—magnified by a religious environment that suppresses her queer identity—forms a psychological landscape riddled with shame, rebellion, and a desire for control.

As she matures, Kari transforms into a social chameleon, adopting various personas to slip through the cracks of societal expectation and punitive judgment. She is simultaneously manipulative and self-aware, charming and destructive, capable of grand empathy and moral lapses.

Her stint as a grifter, marked by forgeries and fraud, is less a tale of villainy and more a desperate act of self-fashioning—a way to assert agency in a world that has denied her coherent identity. Even in her most harmful acts, Kari retains a core of vulnerability that makes her impossible to reduce to stereotype.

Her eventual journey toward self-reckoning—through incarceration, therapy, activism, and storytelling—reveals an extraordinary resilience. In her later years, Kari emerges not as a rehabilitated criminal or reformed sinner, but as a woman of depth, contradiction, and courage, who refuses to be simplified or silenced.

Elliot

Elliot is introduced as a seemingly minor character—a government contractor Kari meets during a chaotic night of escapism—but he gradually becomes a pivotal presence in her post-incarceration life. While their initial connection is rooted in recklessness and emotional dislocation, Elliot proves to be a surprisingly grounding figure.

He is portrayed as emotionally repressed, stoic, and haunted by the burdens of his work, likely suffering from the quiet ravages of systemic complicity. Despite his flaws and uncertainties, Elliot offers Kari a rare form of stability.

He supports her through her attempts at rehabilitation and reinvention, eventually marrying her in an intimate rooftop ceremony that marks a turning point in her emotional narrative.

Elliot’s character serves as a foil to Kari’s chaos. Where she is performative, impulsive, and driven by internal contradictions, he is reserved, consistent, and grounded.

Yet, their bond is not one of savior and saved—it is a mutual refuge. Elliot offers Kari acceptance without judgment, while Kari gives him a glimpse of emotional rawness and unpredictability.

In this dynamic, Elliot becomes a symbol of what Kari has always craved: not perfection, but a space where she can be messy, scared, and honest without fear of abandonment. His role is less about heroism and more about witnessing—he sees Kari fully, not despite her past but inclusive of it.

Spades

Spades, the gender-fluid inmate Kari befriends in Riverside Correctional Facility, stands out as a beacon of resistance, complexity, and unexpected tenderness. Their presence challenges the rigid binary structures of prison and religion that have haunted Kari’s past.

Spades is emotionally layered, both fierce and sentimental, with their treasured stash of perfume ads serving as a symbol of their connection to a deceased mother and the fragility of memory in an institution that seeks to erase individuality. Their orchestrated riot in retaliation for the guards’ cruelty is an explosive act of protest, one that Kari initially resists but ultimately becomes enmeshed in, revealing the ways in which solidarity and defiance can emerge from trauma.

Spades’ impact on Kari is profound. They offer protection, but more than that, they provide a model of integrity and bravery in the face of institutional dehumanization.

Even in punishment, Spades garners respect and support from fellow inmates, becoming a figure of mythic proportions within the prison community. Their bond with Kari is deeply emotional and emblematic of the authentic connections forged in spaces where survival depends on both cunning and care.

Through Spades, Kari not only finds a protector but also glimpses a kind of righteous anger and unfiltered self-expression she has long suppressed.

Charlie Connors

Charlie Connors represents both the tenderness and tragedy of Kari’s early adult life. A kind-hearted drummer from Salt Lake City, Charlie is initially unaware of the full extent of Kari’s manipulations when she inserts herself into his life.

Their relationship begins with the promise of romance and mutual interest, rooted in the idealism of youth and the curated personas of early internet culture. However, as Kari’s trauma-fueled grifting escalates, Charlie becomes one of her first major victims.

His trust is exploited, his financial well-being compromised, and his personal safety endangered when Kari implicates him—knowingly or not—in her fraudulent schemes.

Charlie is not portrayed as a naïve fool but as someone deeply betrayed by love and manipulation. The emotional weight of their relationship lingers beyond Kari’s jail time, serving as a symbol of what is lost when survival comes at the cost of truth.

Charlie’s role in the narrative is important not just as a victim, but as an early mirror to Kari’s own self-loathing and desire for control. He represents the collateral damage of her pain, and her eventual acknowledgment of the harm she caused him is one of the earliest signs of her growing moral awareness.

Gareth

Gareth, the shady manager of the Kurt Hotel—a semi-legal halfway house where Kari resides post-incarceration—is a character shrouded in ambiguity and discomfort. He is emblematic of the murky systems that claim to offer rehabilitation while engaging in surveillance and exploitation.

Gareth records phone calls, hides cash, and exhibits erratic behavior that leads Kari to suspect she is being watched, a paranoia that echoes the surveillance state mechanisms she encounters elsewhere in her life. His presence keeps Kari on edge and adds a layer of psychological tension to her attempts at reintegration.

Yet Gareth is not overtly antagonistic; rather, he reflects the structural dysfunction that surrounds marginalized individuals trying to rebuild their lives. His hotel is simultaneously a shelter and a trap, offering Kari a place to stay but at the cost of autonomy and peace.

Gareth’s character underscores the pervasive sense of being watched, judged, and never truly free—regardless of legal status or physical release from prison. He contributes to Kari’s heightened state of vigilance and becomes one of many reminders that true freedom, for her, is not about geography but about the eradication of shame and fear.

Madyson and Haylee

Madyson and Haylee are fellow inmates who represent the emotional and systemic injustices embedded in the prison-industrial complex. Madyson, a heroin user with a vulnerable core, challenges Kari’s assumptions about addiction and resilience.

She is portrayed as raw, unpredictable, but also deeply reflective, embodying the paradoxes of those caught in cycles of poverty and incarceration. Her presence forces Kari to confront the broader failures of society to address mental health, substance abuse, and trauma with anything other than punishment.

Haylee, a pregnant former high school peer, adds a layer of poignancy and tragedy. Her story is one of lost friendships, broken systems, and the unbearable weight of motherhood in confinement.

Through Haylee, Kari sees the stark reality of her own journey and the privilege she retains even within incarceration. These women are not side characters—they are prisms through which Kari understands the injustices of the world and the capacity for kinship within suffering.

Together, Madyson and Haylee enrich the memoir’s emotional texture, deepening Kari’s transformation from self-serving grifter to empathetic advocate.

Analysis of Themes

Racial Otherness and Adoptive Identity

Kari Ferrell’s experience as a transracial adoptee forms the emotional and sociocultural foundation of You’ll Never Believe Me. From the earliest moments of her childhood, Kari is hyper-aware of her racial visibility in an overwhelmingly white environment, and this difference is neither gently acknowledged nor meaningfully engaged with by those around her.

Instead, it becomes the grounds for mockery, exoticization, and exclusion. Her use of humor and verbal skill to deflect bullying underscores a theme of survival through linguistic performance, but it also reveals the psychological cost of having to constantly defend her existence.

Her parents, while loving and supportive, lack the tools to help her navigate the specific challenges of growing up Korean in white America. Their good intentions are often rendered ineffective by a failure to grapple with cultural nuance, leaving Kari with a fractured sense of self.

Her playful yet painful show-and-tell moment with her “Legal Resident Alien” card exemplifies this duality of internalizing one’s status as both beloved and alien. These early racialized experiences seed a lasting feeling of unbelonging and displacement that echo throughout the memoir.

The disconnect between her family’s emotional warmth and the world’s racial cruelty instills a chasm in Kari’s identity—a tension between gratitude and grief, assimilation and authenticity, safety and visibility.

Religious Indoctrination and Sexual Repression

The conversion of Kari’s family to Mormonism adds an institutional dimension to the forces attempting to control her identity. The faith structure not only promises spiritual stability but also imposes a regime of behavioral conformity, especially in the realms of gender and sexuality.

Within the church, Kari encounters an ideology that idealizes female purity, demonizes queer identity, and demands emotional and sexual confession to male authority figures. Her recollection of being coerced into sharing intimate thoughts with church elders illustrates the psychological damage of religious surveillance and shame.

These experiences repress her emerging queer identity and entangle her in cycles of guilt and secrecy. The rites of the church, from baptisms for the dead to ritualized prayers, serve more as performative submission than spiritual guidance.

While Kari initially seeks comfort and belonging within the religious community, she quickly realizes that her existence as a queer Korean adoptee does not fit within its doctrinal expectations. This mismatch not only isolates her further but also sets the stage for her later rebellion.

Religion here becomes not a sanctuary but a mechanism of containment—one that disciplines the body, distorts desire, and reinforces her alienation under the guise of moral salvation.

Body Image, Shame, and the Currency of Appearance

In You’ll Never Believe Me, Kari’s relationship with her body reflects broader societal pressures around beauty, race, and self-worth. From a young age, she learns that her body is always under scrutiny—whether in the form of schoolyard teasing, public weigh-ins, or beauty standards imposed by the media and the Mormon church.

The humiliating scene at the “pay-what-you-weigh” restaurant distills the shame-based dynamics of body surveillance into a single, absurd event. Yet Kari’s narrative doesn’t reduce these experiences to passive victimhood.

She recognizes the ways her appearance can be manipulated for both protection and power. Her body becomes a site of rebellion, attraction, punishment, and survival.

Food, meanwhile, becomes emotionally charged—offering comfort and autonomy in one moment, and triggering guilt or loss of control in the next. Kari’s body image struggles are not isolated but deeply connected to her racial and sexual identity.

Her sense of worth is constantly filtered through external gazes, and the memoir reveals the insidious effects of a culture that commodifies beauty while punishing deviation from its narrow norms. As she matures, Kari both internalizes and resists these messages, leading to a complicated embodiment marked by contradiction—embracing bold fashion and sexuality while navigating deep wounds left by years of objectification and shame.

Performance, Deception, and the Construction of Self

Kari’s transition into grifting is portrayed not as a sudden moral collapse but as an extension of the performances she’s been conditioned to give since childhood. Whether defending herself from racism, pretending to fit in at church, or navigating adult spaces with charm and improvisation, Kari learns early on that survival often depends on her ability to control narratives.

Her scams—ranging from forged checks to falsified résumés—are less about monetary greed and more about asserting agency in a world that constantly misrepresents her. Her relationship with Charlie, for example, is not just a love affair gone sour but a desperate attempt to belong, to be indispensable.

Each lie becomes both a mask and a mirror, reflecting her unmet needs and her longing for control. The high-stakes deception eventually becomes addictive, providing short-term relief from long-term alienation.

But Kari is acutely self-aware; her tone throughout the memoir oscillates between mockery and melancholy. She acknowledges the harm she caused while exposing the societal structures—racism, classism, and institutional neglect—that shaped her behaviors.

Performance is never just theatrical; it’s survivalist. Kari’s journey reveals how deception can serve as a coping mechanism, a form of protest, and ultimately, a path toward self-awareness, albeit paved with broken relationships and public shame.

Incarceration, Solidarity, and Systemic Failure

Kari’s time in jail is marked by moments of absurdity, pain, and unexpected community. While incarceration is brutal and dehumanizing, it also becomes a crucible for connection and revelation.

Her bond with Spades during the perfume riot is emblematic of how resistance can emerge from shared loss and indignity. The jail becomes a microcosm of systemic inequity, particularly in its treatment of women, queer individuals, and people of color.

Within its confines, Kari begins to understand the broader patterns of dispossession that unite her with fellow inmates. The violence of the carceral system is not just physical but deeply psychological—reflected in the use of solitary confinement, public shaming, and emotional degradation.

Yet, in the midst of this, there are glimpses of humanity: cooking meals with commissary ingredients, fashioning beauty from floss and colored pencils, and staging small rebellions. These moments resist the institution’s attempt to erase individuality and dignity.

Kari’s realization that many incarcerated women are not inherently criminal but simply failed by every prior system—education, housing, healthcare—leads her toward a more radical empathy. Her incarceration is not just a punishment but a transformative experience that shifts her understanding of justice, power, and responsibility, marking the beginning of her political and emotional evolution.

Reinvention, Redemption, and the Politics of Narrative

After prison, Kari’s life becomes an experiment in reinvention. The memoir documents her attempt to build a new identity—not by erasing her past but by confronting it with honesty and humor.

Her marriage to Elliot, her foray into therapy, and her exploration of the Korean concept of han all point toward a deeper reckoning with her traumas and contradictions. Reinvention here is not framed as a clean break or triumphant redemption but as an ongoing process marked by relapse, doubt, and reflection.

Kari’s decision to launch Without Wax Productions and dedicate herself to storytelling for marginalized voices signals a shift from self-preservation to collective advocacy. The memoir also raises questions about the ethics of commodifying trauma: should one profit from their pain?

Can a story rooted in deception ever become a vehicle for truth? Kari ultimately suggests that control over one’s narrative is itself a form of justice.

Her arc refuses a simplistic moral resolution, instead presenting transformation as messy, nonlinear, and deeply human. The public label of “Hipster Grifter” may linger, but Kari reclaims her name and voice through authorship, signaling not just a new chapter but a new authorial authority.

Her journey is a testament to the power of storytelling to reconstruct identity—not as fiction, but as intentional and radical truth-telling.