A Grandmother Begins the Story Summary, Characters and Themes

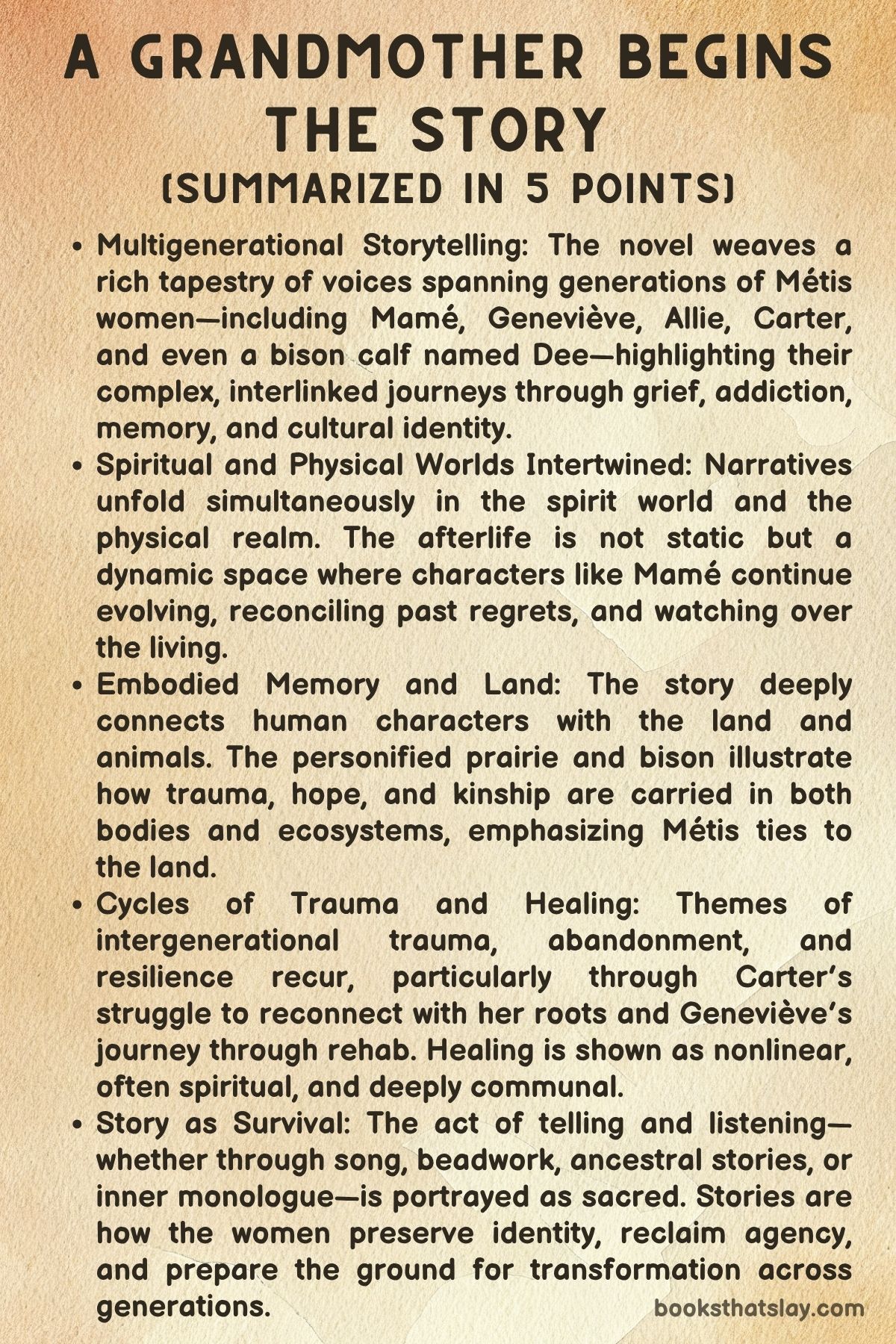

A Grandmother Begins the Story is a poetic and genre-defying debut novel by Michelle Porter. It blends realism and the spiritual to explore the lives of five generations of Métis women and a sentient bison calf.

Told through a chorus of human, animal, and ancestral voices, the novel moves between the living and the spirit world, present and past. It uses short vignettes instead of traditional chapters. At its heart, it’s a story about inheritance—of trauma, love, stories, and identity. The novel centers on the complex work of healing.

Porter fuses Métis worldview, oral storytelling traditions, and contemporary struggles. The structure is as fluid as memory itself.

Summary

The novel opens with Mamé (Élise Goulet), a grandmother who speaks from the afterlife. She reflects on her life, especially choosing love and music over religious expectations.

Mamé expresses a desire to reconnect with the family she left behind. In the spirit realm, time moves differently, allowing her to watch over her descendants and the legacies she has passed down.

One of Mamé’s living descendants is Carter, a Métis woman who was adopted out of her birth family. She has lived her life disconnected from her roots and burdened by unresolved trauma.

When Mamé contacts Carter from beyond, asking for help in dying, Carter is suspicious but intrigued. This request sets Carter on a reluctant path toward reconnection—with her biological mother Allie, her half-sisters, and her lost cultural identity.

Meanwhile, Geneviève, Mamé’s daughter and Carter’s grandmother, is confronting her aging and mortality. She checks herself into a rehab center and reflects on her past relationships and lost memories.

Geneviève’s story addresses aging, addiction, and memory loss. Yet it also reveals her strength and defiance, as she fights against being reduced to just her decline.

In a parallel narrative, the novel introduces Dee, a young bison calf. Dee is separated from her herd and relocated, mirroring themes of Indigenous displacement.

Her journey brings her into contact with a young bull named Jay. Later, she is guided by elder cows who prepare her for motherhood.

Dee’s arc is about personal growth as well as cultural and ecological survival. As she nears childbirth, she questions her role and future, seeking meaning beyond tradition and fear.

The prairie grassland itself speaks as a character. It observes the shifting seasons and events, offering commentary on destruction, renewal, and the interdependence between land and life.

Mamé’s spiritual narrative deepens as she encounters ancestors and memories. She seeks forgiveness and tries to understand how to pass wisdom on.

Her love of music and storytelling shapes her purpose in the afterlife. Her voice becomes both a bridge to the living and a guide for healing.

Carter, meanwhile, struggles with guilt over her son Tucker and bitter feelings toward Allie. Her experiences working in hospice care haunt her with questions of meaning and loss.

Slowly, Carter takes small steps toward healing. She beads with her sisters, texts her adoptive mother, and finally agrees to meet Mamé.

Geneviève’s condition worsens at the rehab center. Her journey, both physical and emotional, leads to moments of insight, connection, and release.

She forms a fragile bond with Pamela, a young nurse. Their exchanges reflect shared vulnerability and the limits of expression across generational lines.

As the story nears its end, Dee prepares to give birth. She represents continuity and future possibility.

Mamé joins the spirit herd of bison. Her presence merges fully with the ancestral current that animates the world.

Carter reaches out to both her mothers in a step toward reconciliation. Her act acknowledges the tangled yet enduring ties of family and story.

The grandmothers—living and spiritual—continue to watch, guide, and hope. Their shared legacy is one of survival, resilience, and truth.

Characters

Mamé (Élise Goulet)

Mamé is the spiritual cornerstone of the novel, a grandmother in the afterlife who is both reflective and yearning. From her place in the spirit world, she contemplates her choices in life—particularly her defiance of Catholic norms in favor of love, music, and a Métis identity.

Her voice is poetic and often filled with sorrow as she tries to connect with her descendants and atone for the pain she caused. In the afterlife, Mamé is not at peace; her feet still ache from a life of hardship, symbolizing the enduring nature of generational trauma.

Yet, she finds herself surrounded by ancestral spirits and buffalo. Gradually, she shifts from regret to a deeper understanding of her role as both storyteller and matriarch.

Her narrative arc is one of spiritual evolution. She moves from being a woman haunted by her past to a grandmother who accepts the sacred duty of guiding and witnessing the healing of future generations.

Geneviève

Geneviève, Mamé’s daughter, is a complex, aging woman grappling with the weight of memory loss, past loves, and her strained maternal relationships. A pianist who has endured personal losses and struggles with alcoholism, Geneviève checks herself into rehab not as an act of surrender, but of rebellion and resolve.

Her journey is both physical and metaphysical—through music, memory, and encounters with spirits, she comes to terms with her life’s failures and triumphs. Geneviève’s interactions with her dogs, her tarot cards, and her nurse Pamela paint a portrait of a woman caught between sharp wit and quiet despair.

Though often guarded, her journey reveals a fierce desire to leave something whole behind—a truth, a story, a thread of forgiveness. Even as her body fails her, she searches for meaning and legacy.

Carter

Carter is perhaps the most contemporary and emotionally volatile character in the novel. Adopted out and disconnected from her Métis roots, she navigates a life marked by trauma, sarcasm, and restlessness.

Her relationship with Mamé begins with suspicion and dark humor but slowly morphs into something more intimate and transformative. Carter is deeply wounded—by abandonment, toxic familial dynamics, and her own choices.

Her bitterness often masks vulnerability, especially regarding her son Tucker, from whom she’s estranged. Through beading, dancing, and spiritual encounters, she begins to reclaim parts of herself.

Carter’s growth is marked not by sudden revelation but by slow, painful reckonings. Her eventual willingness to engage with her grandmothers and face her past points toward the possibility of healing, not just for herself but for the generations before and after her.

Her character embodies the difficult, unglamorous work of reconnection and recovery.

Dee

Dee, a young bison calf, adds a mystical, allegorical dimension to the novel. Her voice is curious, angry, and gradually wise as she navigates displacement, motherhood, and tradition.

Born in the wild and later captured and brought to a fenced facility, Dee’s journey mirrors those of the human women—marked by rupture, resilience, and reclamation. Through her relationships with her mother Roam, the bull Jay, and the elder cow Solin, Dee learns not only survival but the importance of communal wisdom and spiritual inheritance.

Her pregnancy becomes a pivotal turning point, transforming her from a questioning adolescent into a symbol of rebirth and future. Dee’s connection to the grassland and the bison elders speaks to Indigenous relationships with the land, animals, and memory.

As she grows into her role, Dee carries not just her calf, but the weight of storytelling, identity, and ancestral hope.

Velma

Velma, Geneviève’s deceased sister, appears intermittently from the spirit world. Though her physical presence is gone, her influence lingers in Geneviève’s memories and music.

Velma is an emblem of lost potential and unspoken grief. Yet her quiet gaze from the afterlife brings a sense of protection and watching.

Her legacy as a musician infuses Geneviève’s character with both longing and inspiration. Velma’s presence in the afterlife is gentle but powerful, suggesting that the spirits of loved ones continue to shape the living in subtle but meaningful ways.

Allie

Allie is Carter’s biological mother, whose attempts at reconnection are tentative and strained. She represents the many mothers in the novel who have been separated from their children—whether by circumstance, choice, or colonial disruption.

Allie’s relationship with Carter is marked by discomfort, awkward silences, and moments of tentative intimacy, such as shared beading. Though she is not as central as other characters, Allie’s presence underscores the theme of broken maternal lines and the persistent desire—however clumsy or quiet—to repair them.

Themes

Intergenerational Trauma and Healing

One of the central themes in the novel is the inheritance of trauma across generations and the varying ways Métis women attempt to understand, carry, and heal from it. The narrative follows multiple women—Mamé, Geneviève, Allie, Carter—and traces how pain, abandonment, and silence are passed down like heirlooms.

Mamé’s choices, particularly those made out of desire and survival, ripple through her descendants’ lives. She expresses deep regret in the afterlife, acknowledging how her actions affected her daughters and, indirectly, her great-great-granddaughter Carter.

Geneviève, battling memory loss and aging, holds a mirror to this inherited pain, sometimes expressing it through music, other times through silence and detachment. Carter, a product of the sixties scoop, wrestles with the severing of cultural ties and maternal connection, constantly oscillating between anger, numbness, and a desperate hunger to belong.

These women, though disconnected in life, are spiritually linked, and their stories intersect in ways that allow moments of reconciliation and reflection. The act of storytelling—through songs, dreams, beading, and shared memories—becomes a form of healing.

What emerges is a layered portrait of how trauma lingers, but also how it can be addressed when truth is spoken and vulnerability is allowed. The cyclical structure of the book mirrors this theme, demonstrating that healing is neither linear nor guaranteed, but possible through intentional acts of remembrance and connection.

The theme affirms that ancestral pain can be confronted—not necessarily resolved—but witnessed and softened through intergenerational understanding.

Matriarchal Power and Ancestral Guidance

The book is rooted in the strength and wisdom of women across generations. It centers the matriarch not as a static figure but as a complex, evolving force that continues to shape lives even beyond death.

Mamé, occupying a space in the afterlife, serves as a spiritual observer and participant. Her presence underscores the role of grandmothers not just as caretakers, but as storytellers, teachers, and bridges between the living and the dead.

The narrative demonstrates how matriarchal power is often quiet, cyclical, and emotional rather than dominant or hierarchical. Geneviève, despite her physical decline and memory loss, embodies a different form of power—resilience through age and a refusal to surrender to pity.

Her connection to music and rituals hints at the importance of embodied knowledge and feminine intuition. Carter, caught between multiple mother figures—biological, adoptive, and spiritual—represents the tension and potential within matriarchal legacies.

The bison elders, Solin in particular, expand this theme into the animal world, showing how leadership and care are passed through maternal lines even in non-human characters. This multi-layered representation of matriarchy is further spiritualized through scenes with ancestral spirits and personified land.

The grandmothers in the spirit world are not passive but active, searching, observing, and offering quiet counsel. This vision of matriarchy is deeply Indigenous—communal, spiritual, and relational.

It challenges Western notions of lineage and power by suggesting that true authority comes from memory, ritual, and relationship with land and story.

Displacement and the Search for Belonging

Displacement in the novel is both literal and metaphorical. It is experienced by humans and animals alike, with Dee the bison calf representing a powerful symbol of forced removal and adaptation.

From the moment she is separated from her herd, tranquilized, and transported to an unfamiliar place, Dee becomes a mirror of Indigenous displacement. Her journey reflects the broader history of colonial disruption, in which beings are torn from ancestral places and made to adapt in environments that often feel alien or hostile.

Her longing for Roam, her mother, parallels the ache of adopted or disconnected Indigenous children like Carter, who struggle to forge identity from fragments. Carter’s own dislocation—from her culture, her son, and even her selfhood—manifests in bitterness, sarcasm, and emotional volatility.

Her journey toward reconnection is rocky and uncertain, often haunted by the weight of not belonging anywhere fully. Geneviève’s move to the rehab center is another form of self-imposed exile, chosen in part to confront the detritus of the past.

Even Mamé, though dead, experiences a form of displacement in the afterlife, caught between cultural belonging and spiritual assimilation. The land itself—grasslands that speak and fences that weaken—emphasizes that displacement is not only a human issue but an ecological and spiritual one.

Ultimately, the search for belonging unfolds not through resolution but through gradual gestures of return. Carter texting her mother, Dee rejoining the herd run, Geneviève playing a piano—these moments, while small, create space for reconnection and restoration of disrupted ties.

Storytelling as Survival and Resistance

Storytelling permeates every level of the novel, operating as a means of survival, cultural preservation, and emotional resistance. Each character’s narrative contributes to a larger mosaic of meaning, and each story, whether spoken, remembered, or imagined, becomes a tool for transformation.

The structure of the book itself—fragmented, multi-voiced, nonlinear—reflects the oral traditions of many Indigenous cultures, privileging rhythm, repetition, and circularity over traditional plot. Mamé’s role in the afterlife is to tell and retell stories, positioning storytelling as a sacred duty that extends beyond death.

These stories are not just about remembering the past but about influencing the present and shaping the future. The animal voices, particularly Dee and the prairie grass, add an ecological dimension to storytelling, reminding readers that narratives are held in landscapes, not just in human memory.

Carter’s work in hospice care shows how stories are used at the end of life to make sense of pain. Geneviève’s tarot reading and piano playing suggest that stories can also be found in symbols and sounds.

Beading, too, becomes a narrative form, allowing Carter to stitch pieces of herself back together, even when her words fail. The elders’ oral teachings, especially those passed to Dee, show how storytelling serves as a bridge between generations and a safeguard against cultural erosion.

In this way, storytelling in the novel is not just a literary device—it is an act of resistance against silencing, erasure, and forgetting. It is both a method of survival and a declaration of continued presence.