Baumgartner by Paul Auster Summary, Characters and Themes

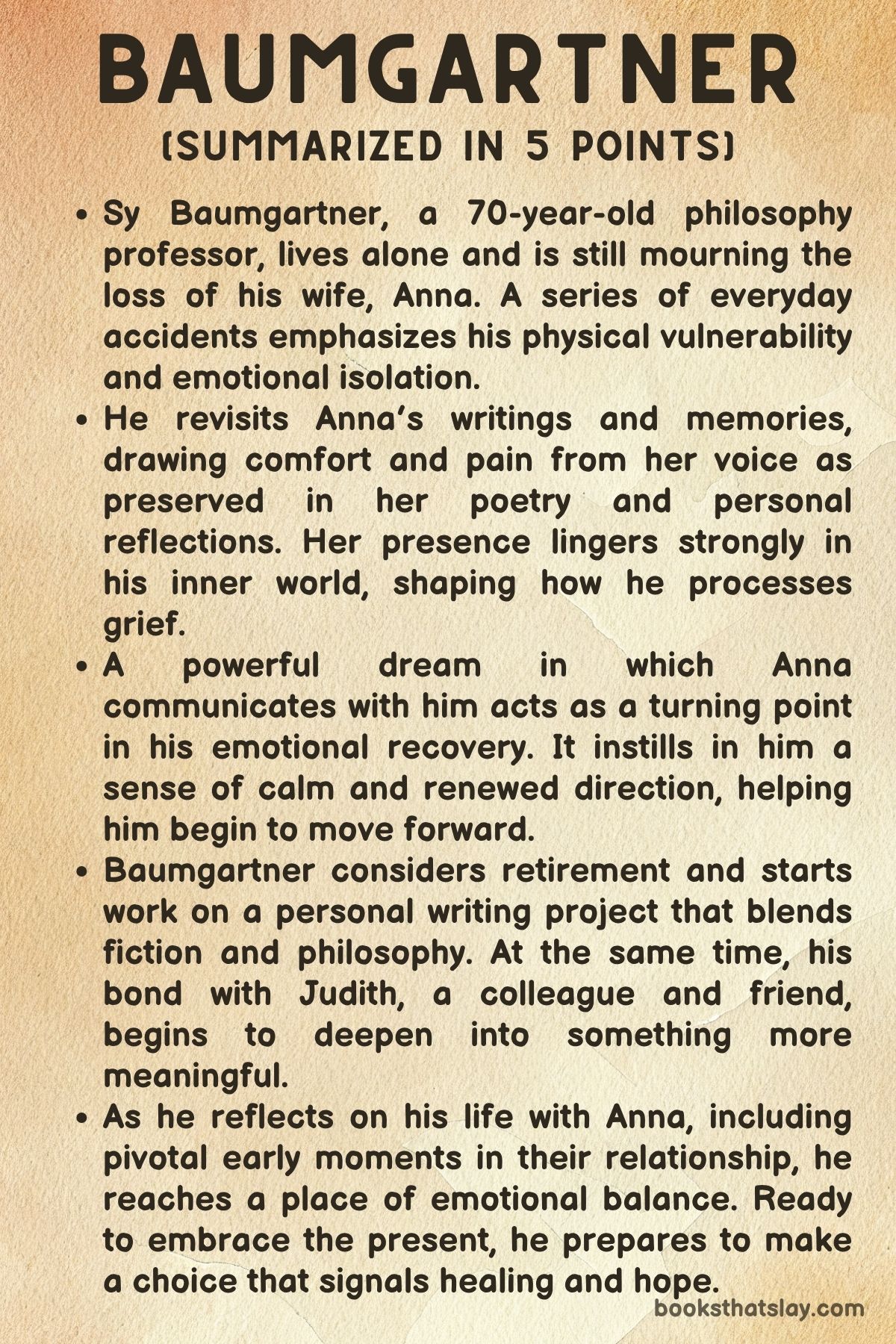

Baumgartner by Paul Auster is a contemplative and intimate novel by Paul Auster that traces the emotional landscape of Sy Baumgartner, a seventy-year-old philosophy professor grappling with the long shadow of grief.

Set years after the sudden death of his beloved wife Anna, the story quietly examines aging, memory, and the human capacity for renewal. Through episodes of solitude, remembered love, intellectual exploration, and tentative new beginnings, Baumgartner’s inner world unfolds in quiet, poignant layers.

Auster blends philosophical musing with grounded, everyday moments to portray a man caught between past devotion and the possibility of future connection.

Summary

Sy Baumgartner, a retired philosophy professor in his seventies, lives alone in Princeton, New Jersey.

His wife Anna, a poet, died nine years earlier in a tragic swimming accident, and he has since struggled to move forward.

The story opens with a sequence of minor domestic incidents that reflect his current state—he burns his hand while making coffee, forgets to call his sister, and falls down the basement stairs after being distracted by a UPS delivery.

These physical stumbles parallel his emotional fragility and isolation.

A chance interaction with a friendly meter reader, Ed, who helps him after his fall, reminds him of the quiet kindness still possible in the world.

That evening, the sight of an old pot sparks the memory of the day he met Anna, underlining how much of his present is haunted by his past.

In the summer, Baumgartner becomes fascinated by phantom limb syndrome, using it as a metaphor for grief.

Just as amputees feel the presence of lost limbs, he feels Anna’s absence as a constant presence.

He revisits her writing, including unpublished poems and a personal essay about Frankie Boyle, a childhood friend and first love who died in a military accident.

Baumgartner helped edit Anna’s work after her death and had her poetry posthumously published, continuing her voice in the world.

He reflects on how mourning alters perception—how memory can keep a person partially alive.

This chapter reveals the depth of their bond and the ongoing emotional weight Baumgartner carries.

One night, he dreams that Anna speaks to him on a red rotary phone, describing death as the “Great Nowhere.”

In this vision, she says she continues to exist only because he remembers her.

The conversation brings Baumgartner a strange peace, shifting his inner sense of confinement into something more open and alive.

Waking from the dream, he feels a subtle but real transformation.

He starts to consider the possibility of change and reengagement with life.

Buoyed by this emotional clarity, Baumgartner decides to retire from academia and focus on writing a book called Mysteries of the Wheel, an introspective exploration of identity, memory, and relationships.

He also begins to reflect more seriously on his relationship with Judith Feuer, a film studies professor and long-time acquaintance.

After Anna’s death, Judith had reached out to him out of concern, and over time their bond evolved into a quiet companionship that became romantic.

Judith, sixteen years younger and a mother, contrasts with Anna in many ways, but Baumgartner recognizes that this difference does not diminish the connection.

He debates whether to propose marriage, uncertain about how she might respond.

As he contemplates this new chapter, he finds a box in Anna’s old office containing a personal essay she wrote titled “Spontaneous Combustion.”

In it, she recounts the night he proposed to her after she narrowly escaped being mugged.

That moment of vulnerability had crystallized their love and led to a spontaneous, deeply human exchange that shaped their future.

Her description of the New York of the 1970s, her work in publishing, and her passionate pursuit of poetry come alive on the page.

Reading her words once again, Baumgartner is filled with gratitude for their shared life, but he no longer feels defined by the loss.

By the novel’s end, Baumgartner is prepared to ask Judith to marry him.

He no longer lives in the shadow of the past but carries it with him into a future that still holds meaning.

The book closes with Baumgartner choosing presence over memory, love over solitude, and the possibility of beginning again.

Characters

Sy Baumgartner

Sy Baumgartner is the emotional and philosophical center of the novel—a retired philosophy professor confronting the fragility of old age and the enduring shadow of grief. His daily mishaps, such as burning his hand or falling down the stairs, highlight not only his physical vulnerability but also his disoriented emotional state following the death of his beloved wife, Anna.

Baumgartner’s journey is one of quiet metamorphosis: from a man paralyzed by sorrow and memory to someone who slowly, and almost reluctantly, reorients himself toward life again. His grief manifests not only as a longing for the past but also as a complex intellectual inquiry; he studies phantom limb syndrome to better articulate the emotional phenomenon of loss.

The dream sequence with Anna marks a spiritual turning point, symbolizing his tentative steps out of the long night of mourning. As he begins to re-engage with the world—through writing, retirement, and a renewed romantic relationship—Baumgartner evolves from a widower frozen in time to a man capable of embracing change, love, and vulnerability once again.

Anna Baumgartner

Anna, though deceased, exerts a powerful posthumous influence over the narrative and Baumgartner’s psyche. She is portrayed not just as a lost wife, but as a vivid intellectual, poet, and fiercely independent spirit.

Her childhood, marked by privilege, served as the backdrop against which she defined her identity through rebellion and literary ambition. Anna’s autobiographical writings, especially about her early love Frankie Boyle and her near-mugging experience, reveal her complex emotional landscape and foreshadow her capacity for intense connection and fearlessness in the face of trauma.

Through Anna’s words and memories, we come to see her as more than a static object of grief; she is a living presence in the text, shaping Baumgartner’s ongoing identity and inner dialogue. Her death becomes a prolonged echo rather than an end, and her final story, “Spontaneous Combustion,” provides both a window into her personality and a mirror for Baumgartner to reflect on love, loss, and renewal.

Judith Feuer

Judith represents the possibility of a future untethered from loss. A film studies professor and long-time acquaintance, she becomes a source of emotional grounding and potential romantic renewal for Baumgartner.

Unlike Anna, Judith is a mother and comes from a different emotional terrain—her connection with Baumgartner emerges not from shared history but from mutual empathy and present-tense companionship. Their relationship is marked by caution, affection, and a slow-building intimacy that mirrors Baumgartner’s tentative return to the world.

She is not positioned as a replacement for Anna but rather as a companion who challenges Baumgartner to see himself anew, as someone still capable of love and being loved. Judith’s presence anchors the novel’s shift from elegy to rebirth, from static grief to dynamic choice.

By contemplating marriage with her, Baumgartner symbolically steps out of the long shadow of Anna’s death and into the unpredictability of a future built with someone else.

Ed Papadopoulos

Though a minor character, Ed Papadopoulos, the compassionate meter reader, embodies the theme of unexpected human kindness. His appearance during Baumgartner’s moment of physical crisis—after a fall down the basement stairs—offers not only literal help but also symbolic reassurance that the world still contains empathy and community.

Ed’s unassuming decency serves as a narrative counterbalance to Baumgartner’s sense of isolation, reinforcing the idea that healing and support can come from unlikely places. In a novel steeped in philosophical reflection and internal monologue, Ed’s simple act of kindness feels quietly transformative and reaffirms Baumgartner’s slow re-entry into social and emotional life.

Frankie Boyle

Frankie Boyle, Anna’s childhood love who died in a military training accident, appears only through her memoir, but his presence is significant in constructing Anna’s emotional and psychological history. Frankie represents the formative experience of loss and yearning in Anna’s life, a pattern that echoes in her relationship with Baumgartner.

Her remembrance of Frankie adds emotional texture to her character, revealing that grief was not foreign to her even before her relationship with Baumgartner. It is through Anna’s account of Frankie that we see how deeply she understood the ache of absence and the fragility of connection—insights that inform both her poetry and her partnership with Baumgartner.

Themes

Grief and Memory

The theme of grief in Baumgartner is not merely a background element but the emotional core around which the narrative revolves. From the opening scenes, Sy Baumgartner’s life is shaped by the profound absence of his wife, Anna, who passed away nine years prior.

His grief is not melodramatic but manifests in subtle, persistent ways: through his physical carelessness, the absentmindedness that causes him to burn himself, and the obsessive clinging to memories and objects linked to Anna. Paul Auster represents grief as something that exists not in waves but in echoes, in ghostly presences that never fully dissipate.

The idea of “phantom person syndrome” becomes a philosophical and emotional device through which Baumgartner tries to understand his suffering. It allows him to rationalize his continued connection to Anna and explore how memory keeps the dead alive in one’s psyche.

Even his dreams act as a medium for these lingering attachments, giving Anna a kind of life through Baumgartner’s mental and emotional persistence. His memory functions as a resurrection space, sustaining Anna’s voice and presence despite the physical finality of death.

As he reads Anna’s writings, particularly her autobiographical accounts, the line between past and present blurs. These acts of remembrance, while often comforting, also prevent Baumgartner from fully rejoining life.

Only through sustained emotional reflection and eventual spiritual acceptance does he begin to emerge from the confines of his grief. The book makes it clear that grief doesn’t disappear—it becomes integrated into the self, not erased but recontextualized as part of one’s ongoing life.

Aging and Vulnerability

Paul Auster presents aging as a multidimensional experience in Baumgartner, blending physical vulnerability with emotional resilience. In the early chapters, Baumgartner’s scalding injury and fall are not just accidents; they are symbolic of the body’s decline and the precariousness of later life.

He is portrayed not as a victim of age but as someone quietly navigating the indignities and limitations that come with it. His solitude exacerbates these vulnerabilities, highlighting how aging often isolates individuals from the rest of society.

Yet, Auster does not reduce Baumgartner to a caricature of decrepitude. Instead, he is intellectually sharp, still working, still engaged with philosophical questions, and capable of love.

The theme is expanded as Baumgartner contemplates retirement. His decision is less about giving up and more about choosing a new form of life—one where he is no longer defined by institutional roles but by his own intellectual and emotional needs.

The story acknowledges how the aging process includes not just losses—of vitality, partners, relevance—but also potential gains: wisdom, clarity, and, paradoxically, freedom. The relationship with Judith is also framed through this lens.

While Baumgartner fears rejection due to the age gap, the affection they share suggests that emotional intimacy and renewal are still possible, even late in life. Aging, in this novel, is not portrayed as a descent but as a shifting landscape.

It is full of hazards, yes, but also with its own beauty and significance. It is a state of being where vulnerability becomes a conduit for genuine connection and self-understanding.

Love, Intimacy, and Renewal

The evolution of love across time, loss, and new beginnings is another significant theme in Baumgartner. The novel begins with a portrait of love after loss—Baumgartner’s marriage to Anna is long over in a physical sense, but emotionally he remains bound to her.

The intensity of their relationship, the way he holds onto her writings and memories, shows how love can transcend death. It becomes a force that still shapes one’s worldview and emotional register.

This love, however, is not static. Through the development of his relationship with Judith, Paul Auster introduces a counterpoint: the possibility of love’s renewal.

The affection between Baumgartner and Judith is not presented as a replacement for Anna but as a separate and valid form of intimacy. It is more tentative, shaped by middle-age considerations, but it still carries the promise of emotional fulfillment.

This shift marks a deep psychological transformation for Baumgartner. To love again, he must renegotiate his identity, no longer seeing himself solely as Anna’s widower but as someone capable of new commitments.

The contrast between Anna and Judith—their backgrounds, personalities, and roles in Baumgartner’s life—further emphasizes that love is not a uniform experience. Each relationship carves out its own space in a person’s emotional architecture.

Through Baumgartner’s proposal to Judith and his decision to move forward with her, the novel affirms that love, even after profound loss, is not over. It can take different forms, emerge at different times, and still be deeply meaningful.

Love here is shown not as a singular event but as a continuum—evolving, resilient, and open-ended.

Intellectual Reflection and the Life of the Mind

Paul Auster uses Baumgartner’s identity as a philosopher to frame another central theme: the enduring role of intellectual inquiry in shaping one’s understanding of self and world. Baumgartner does not simply feel his emotions—he interrogates them.

He explores his grief through the metaphor of phantom limb syndrome, uses philosophical questions to examine death, memory, and consciousness, and remains engaged with writing as a means of organizing thought.

His forthcoming book, Mysteries of the Wheel, becomes a symbol of this lifelong habit of reflection. It represents a shift from formal academic work toward a more personal and exploratory form of thought.

The novel positions intellectual life not as detached or sterile but as deeply interwoven with emotion, memory, and lived experience. Philosophy, in Baumgartner’s case, is not abstract but embodied.

It is how he makes sense of loss, how he processes aging, and how he constructs meaning. His dream about Anna and the metaphor of the “Great Nowhere” reflects a mind still probing the boundaries of life and death, even in sleep.

Paul Auster shows that the life of the mind does not fade with age or trauma; instead, it adapts. Even the act of reading Anna’s writings is a form of philosophical engagement.

It prompts Baumgartner to reflect not only on her life but on his own changing understanding of love and identity. This theme reinforces the idea that thought can be a form of resilience.

Contemplation is not an escape from pain but a way of living through it meaningfully.