Heaven Official’s Blessing Volume 8 Summary, Characters and Themes

Heaven Official’s Blessing Volume 8 by Mo Xiang Tong Xiu is the culmination of a long, emotionally charged journey. This final volume brings together loose ends, reveals buried secrets, and delivers closure for its complex characters.

At its core is Xie Lian, a god who has known both divine reverence and mortal ruin, and Hua Cheng, a powerful ghost king who follows him through life and death. The book balances intense confrontations with tender moments, as characters reckon with their pasts and affirm who they want to be.

It’s both a grand finale and a quiet goodbye—bittersweet, sincere, and deeply rewarding.

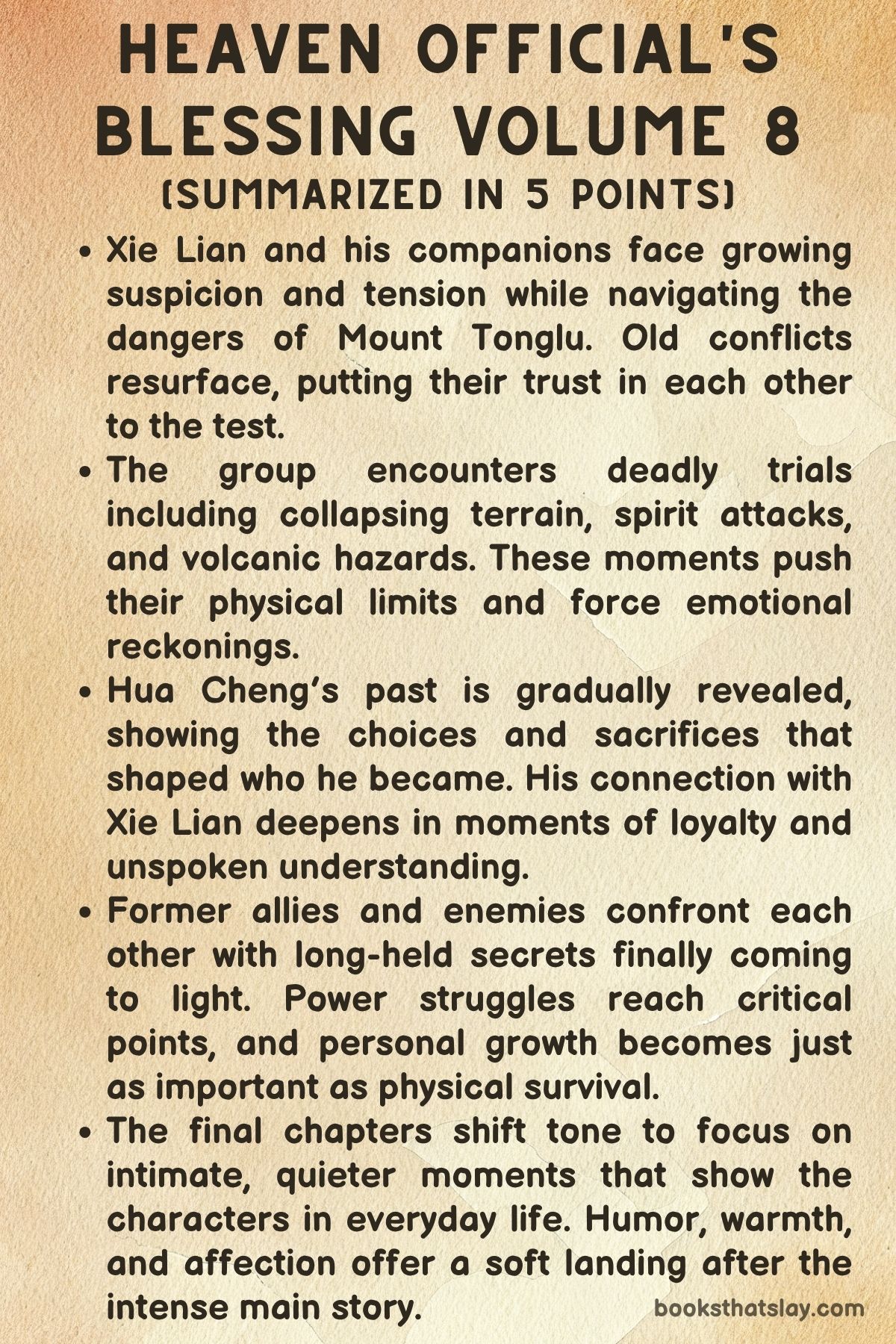

Summary

Volume 8 begins deep within the treacherous heart of Mount Tonglu. Xie Lian, Hua Cheng, Mu Qing, and Feng Xin press forward in their final confrontation against the hidden truths and powerful enemies that have haunted them.

Tensions rise early when Mu Qing and Feng Xin suspect each other of being impostors. Mistrust simmers as the group finds themselves locked in a deadly armory, surrounded by cursed weapons.

Their differences boil over into physical confrontation. Xie Lian works to mediate, reminding them of their shared history and responsibilities.

The group continues deeper into the mountain’s hostile terrain. As molten spirits stir and bridges collapse into rivers of lava, they are forced to rely on one another to survive.

Amidst the danger, old emotions surface—guilt, regret, and silent admiration—especially between Xie Lian and the other former Heavenly Officials. Hua Cheng, as always, remains fiercely protective of Xie Lian, even at the cost of his own safety.

Their path leads them to the Heaven-Crossing Bridge, a symbolic and literal turning point. Here, Mu Qing and Xie Lian share a rare, emotional conversation.

Mu Qing confesses that his earlier contempt came from fear and inadequacy, not disdain. He admits he once admired Xie Lian greatly but couldn’t accept what he himself lacked.

This moment becomes one of mutual understanding and quiet reconciliation. Meanwhile, Hua Cheng and Jun Wu—now revealed to be the mysterious and malicious White No-Face—engage in a brutal fight.

Jun Wu’s plan to control fate and destroy opposition is laid bare. During the battle, Jun Wu reclaims Xie Lian’s former sword, Fangxin, which is revealed to have once been Zhuxin.

The sword symbolizes the long thread of connection and betrayal between the two. Hua Cheng uses Eming, his blood-forged weapon, crafted from a self-sacrificial act meant to spare others.

This act stands in powerful contrast to Jun Wu’s ruthless ambition. As Jun Wu’s true identity and motivations are fully exposed, Xie Lian and Hua Cheng face him together.

Their partnership is seamless, their bond evident even in battle. Xie Lian gives commands almost unconsciously, knowing Hua Cheng will follow.

A final collapse of the Heaven-Crossing Bridge forces a desperate escape. Lava threatens to consume everything.

Feng Xin and Mu Qing each face moments of redemption. Feng Xin grapples with his failure to protect others, and Mu Qing confesses his role in past misunderstandings.

The spiritual and physical inferno brings out truth, vulnerability, and strength in each of them. In the climax, Xie Lian ultimately refuses to give in to hatred or vengeance.

He reaches out with compassion, choosing love over violence. Hua Cheng, badly wounded, stands beside him until the end.

Together, they end Jun Wu’s threat—not by becoming monsters themselves, but by holding on to their humanity.

The extras that follow provide a gentler tone. One story finds the group participating in a lantern festival, full of laughter and light teasing.

Another follows Xie Lian as he loses his memory and must slowly rediscover himself—primarily through his connection to Hua Cheng, which endures even forgetfulness.

There’s also a bedtime story Hua Cheng tells, rich in symbolism. A chaotic adventure in a cave full of gods injects lighthearted fun.

The final extra, “The Ghost King’s Birthday,” shows Xie Lian preparing a surprise celebration for Hua Cheng. Though Hua Cheng claims birthdays don’t matter to him, Xie Lian insists.

He offers a handmade red ribbon as a token of connection and care. Hua Cheng, touched, tells Xie Lian that every day with him is a celebration.

Their quiet moment together marks the end of their journey—not in grandeur, but in peace, love, and hard-earned happiness.

Characters

Xie Lian

Xie Lian continues to embody his complex duality—profound kindness and tragic resilience—throughout Volume 8 of Heaven Official’s Blessing. His character reaches a deeply introspective climax as he grapples with guilt from the past and the weight of choices made over centuries.

In the perilous descent into Mount Tonglu and the face-off against Jun Wu, Xie Lian showcases unshakable resolve without losing his compassion. He mediates tensions among companions, leads with empathy, and shows the maturity of a man who has lived through cycles of glory, shame, and recovery.

What defines him in this volume is not just martial skill or divine authority, but his quiet emotional strength—his belief in redemption and his ability to forgive others, especially Mu Qing and Feng Xin, as well as himself. His unwavering trust in Hua Cheng is instinctual and tender, illustrating how their bond has evolved into a natural, deeply rooted connection.

In the extras, his affection softens further—demonstrating domestic warmth and joy in shared intimacy, especially when celebrating Hua Cheng’s birthday.

Hua Cheng (San Lang)

Hua Cheng’s portrayal in this volume is that of a deeply loyal, emotionally intense being who walks the line between overwhelming power and soft vulnerability. His past is unveiled in greater detail, revealing the sheer scale of sacrifice he made to become a Ghost King—not by harming others, but by giving up parts of himself.

His devotion to Xie Lian is no longer merely romantic but existential; he lives and fights entirely for Xie Lian’s safety and happiness. Even when gravely injured, Hua Cheng defends him with fervent determination.

Notably, he never oversteps emotionally—his love is selfless, quiet, and full of restraint. The extras offer a rare glimpse into his lighter side, as seen in the birthday chapter, where his bashfulness and joy reflect his yearning for normalcy and affection.

The symbolism of the red ribbon and Hua Cheng’s remark that every day with Xie Lian is his birthday beautifully encapsulate his worldview: eternal love anchored not in rituals, but in presence.

Mu Qing

Mu Qing’s character arc is one of the most compelling in this volume, as he is finally forced to confront his own pride, insecurities, and the deep-rooted resentment he harbored toward Xie Lian. Initially suspicious and antagonistic, Mu Qing is trapped—both literally and emotionally—within the confines of guilt and internal conflict.

The journey through Mount Tonglu becomes a crucible that strips away his defensive arrogance, revealing his latent admiration for Xie Lian and regret for past actions. His confession of guilt is raw and emotional, showing a side of him seldom seen—vulnerable and humbled.

His reconciliation with Xie Lian marks the true climax of his personal arc, allowing him a semblance of peace. He remains snarky and pragmatic, but his grudges lose their edge, replaced by a quiet acknowledgment of his own flaws.

Feng Xin

Feng Xin maintains his steadfast, often blunt nature, but Volume 8 also peels back layers of emotional complexity—particularly through his painful connection to the fetus spirit. His moral rigidity is tested as accusations and doubts arise, especially from Mu Qing, who confronts him about fatherhood and unresolved responsibilities.

Unlike Mu Qing, Feng Xin does not spiral into self-loathing, but he does show visible emotional strain and a desire to protect what’s right—even if he’s unsure what that is anymore. His loyalty to Xie Lian remains firm, and his combat prowess continues to be dependable.

Yet it is his quiet moments of introspection and reactions to emotionally charged revelations that give his character more weight. He is not just a loyal guard but a man grappling with what loyalty and responsibility mean in the face of past mistakes.

Jun Wu / White No-Face

Jun Wu’s true identity as White No-Face marks a chilling evolution from divine authority to corrupted obsession. As the former Heavenly Emperor, he represents the dangers of unchecked ambition masked as divine order.

His character becomes the embodiment of manipulation, as he exploits identities, symbols, and psychological weaknesses. What makes him terrifying is not just his power, but his deep knowledge of his enemies’ fears and desires—turning them into weapons.

His mask being shattered is symbolic of his final unmasking—not only in a literal sense but also as the collapse of the illusion of heavenly righteousness he once upheld. His defeat is not just a victory in battle but a moral and spiritual triumph over a doctrine that punished emotion and individual will in the name of divine control.

Themes

Love as Redemption and Devotion Beyond Death

Love in Volume 8 is not a background motif; it is the emotional axis upon which the entire story turns. The bond between Xie Lian and Hua Cheng is portrayed as unbreakable, not because it is free from suffering, but precisely because it survives and is forged through it.

This volume shows love not as fleeting emotion but as a long-enduring act—consistent, sacrificial, and steadfast even in the face of cruelty and hopelessness. Hua Cheng’s devotion is not expressed in poetic declarations but in action: he fights impossible odds, gets wounded without complaint, and prioritizes Xie Lian’s safety and happiness over his own survival.

Similarly, Xie Lian begins to understand the depth of his feelings, not in grand gestures but in quiet acknowledgment. It shows in how instinctively he gives orders to Hua Cheng in battle or how he worries when he’s hurt.

Love becomes a redemptive force for both, grounding Hua Cheng who has lost everything and allowing Xie Lian to believe he is worthy of being loved again. Even in the extras, especially the birthday chapter, the domestic softness serves to underline that after centuries of chaos and isolation, these two characters have chosen each other over immortality, power, or vengeance.

Their love is not an escape but a healing return to life itself.

The Complexity of Identity and the Search for Self

Identity in this volume is not treated as static. Characters shift masks, betray their supposed nature, and confront their past actions as part of coming to terms with who they are.

Xie Lian, once a god-prince, a cursed immortal, a wandering beggar, and now something in between, continuously reshapes his understanding of himself through the mirror of others—particularly Hua Cheng, Feng Xin, and Mu Qing. His arc is not about reclaiming his old glory but choosing who he wants to be after being stripped of it.

Hua Cheng’s identity as the Supreme Ghost King is also challenged by his past. His transformation into a blood-weapons-wielding ghost came from trauma, but he never let that become a license for destruction.

His identity is bound to his belief in Xie Lian, to the point that his name, body, and power exist in relation to that faith. Jun Wu, by contrast, represents the failure to reconcile self with ambition.

His multiple guises—including White No-Face—symbolize a deep fragmentation, an inability to accept who he has become without the trappings of heavenly glory. The extras even play with identity in comedic ways, such as Xie Lian’s amnesia, which humorously explores how much of who he is can be recognized by those who love him.

In the end, identity is portrayed as something that is less about what one is born into and more about what one chooses to be in each moment, especially when no one is watching.

Forgiveness, Reconciliation, and the Burden of the Past

Forgiveness is one of the most morally and emotionally charged themes in the volume. The narrative repeatedly puts characters in situations where they must confront betrayals and losses not just committed by enemies, but by those once closest to them.

The most powerful examples involve Feng Xin and Mu Qing, whose relationships with Xie Lian are riddled with misunderstanding, guilt, and deeply buried affection. Instead of resolving these conflicts through a single act of contrition or apology, the text shows forgiveness as an ongoing, painful process.

Mu Qing’s arc is particularly raw, admitting not just to selfish choices but to the fear and admiration he always carried for Xie Lian. Feng Xin’s reluctance to acknowledge his own faults, especially regarding the fetus spirit, also serves to show that even loyalty is not free from error.

Xie Lian, for his part, offers forgiveness not as moral superiority but as a form of release—from the shackles of the past, from grudges that poison relationships, and from the loneliness that resentment breeds. This theme also intersects with the confrontation with Jun Wu, where justice must be dealt but not necessarily without understanding the twisted roots of his descent.

Forgiveness here is not synonymous with forgetting or excusing, but a deliberate act of choosing peace over eternal retribution. The extras, with their lightness and affection, offer emotional balm to these heavier reckonings, suggesting that while forgiveness is hard-won, it can lead to laughter and intimacy again.

Fate, Choice, and the Reclamation of Agency

The struggle between destiny and personal will is a recurrent philosophical current running through the book. Throughout the main chapters, characters are often confronted with the belief that their paths are prewritten—Xie Lian as the forever-cursed crown prince, Hua Cheng as the doomed ghost king, Jun Wu as the emperor whose divine authority grants him unchecked power.

However, what Volume 8 insists upon is that fate may set the stage, but choice determines the outcome. Xie Lian chooses to believe in people despite repeated betrayals; he chooses mercy when vengeance would be easier.