Hot Springs Drive Summary, Characters and Themes

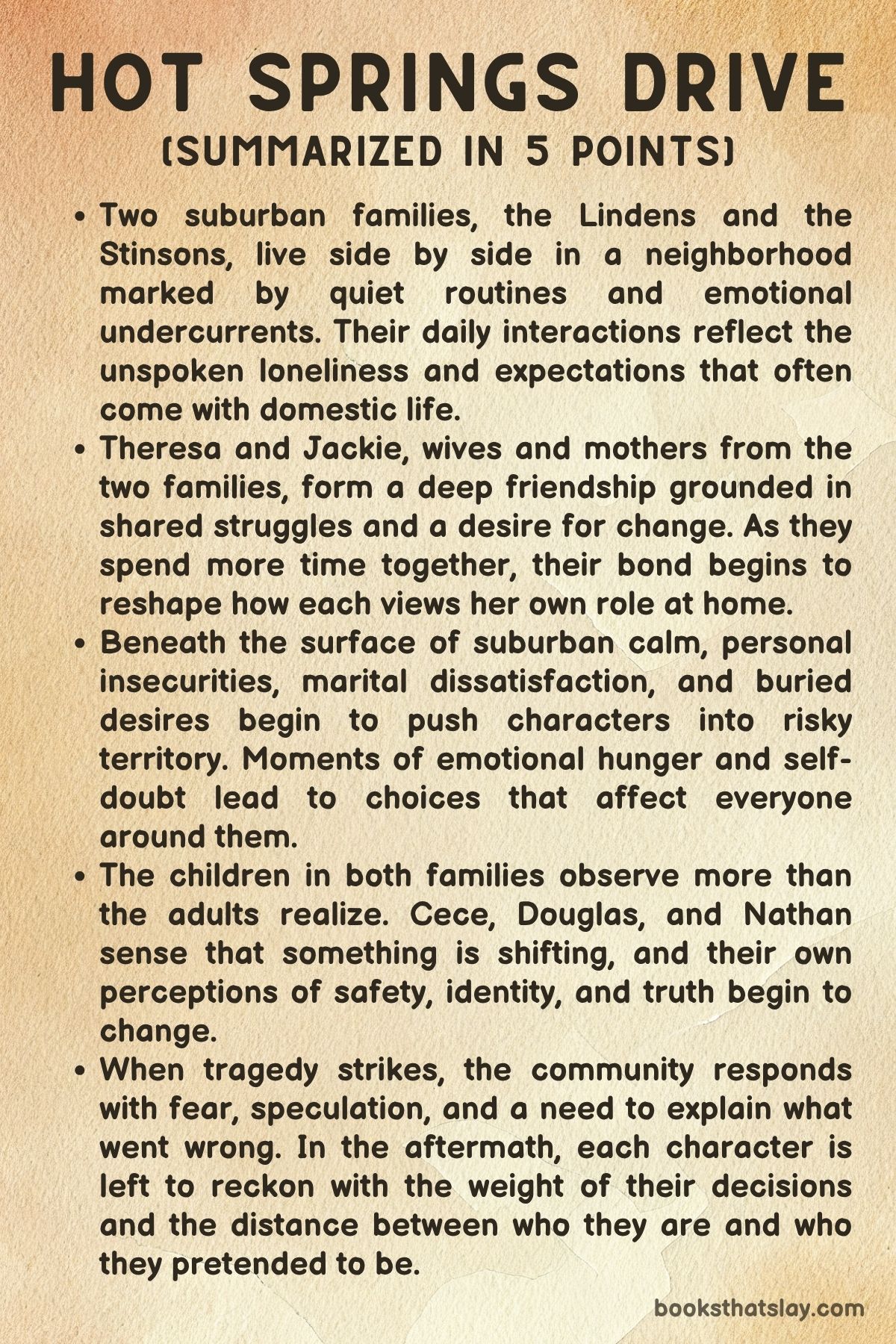

Hot Springs Drive by Lindsay Hunter is a dark, emotionally charged novel that explores the disintegration of suburban life beneath its orderly surface.

Through alternating perspectives and short, sharp chapters, Lindsay Hunter captures the intimate, suffocating proximity of two neighboring families—each grappling with identity, repression, and fractured love. At the center is a brutal crime that exposes the dysfunction, resentment, and unspoken pain simmering in plain sight. Hunter’s writing is raw and fearless, rendering motherhood, adolescence, marriage, and mental instability with unsettling precision.

This is not just a story about a murder, but about the ways ordinary people erode under pressure. It shows how silence and longing can become dangerous.

Summary

In a quiet suburban neighborhood, two families—the Lindens and the Stinsons—live side by side. Theresa Linden is a disciplined mother and wife, defined by her need for control and structure, while Jackie Stinson is a chaotic but charismatic woman buried beneath the demands of motherhood.

Their friendship begins at the hospital when both give birth, and over time, they become emotionally dependent on each other. But what seems like a supportive bond slowly morphs into something more complicated.

Jackie, worn down by raising four sons and emotionally abandoned by her husband Nick, begins to obsess over her body and self-worth. Nick, a car salesman, is emotionally disconnected and dismissive, more interested in flirting with customers than engaging with his family.

Meanwhile, Theresa’s husband Adam is quietly dissatisfied, feeling increasingly distant from Theresa and drawn to Jackie’s newly found confidence. As Jackie and Theresa begin attending a weight-loss group together, their closeness intensifies.

Jackie feels validated for the first time in years, while Theresa—whose daughter Cece is growing more independent—feels emotionally abandoned. Both women use each other as anchors in lives that are quietly falling apart.

Eventually, Adam and Jackie begin a secret affair, driven more by longing and resentment than passion. Jackie’s oldest son, Douglas, is emotionally unstable and disturbed.

He senses something wrong in the adults around him, especially his mother’s closeness with Adam. When he witnesses them having sex, it becomes a psychological breaking point.

He becomes increasingly erratic, isolated, and filled with shame and anger. Cece, Theresa’s daughter, is also changing.

Sensitive and perceptive, she begins to sense that something is deeply wrong with her father, even if she can’t name it. Her sense of safety fades.

Then comes the murder: Theresa Linden is found dead in her garage, bludgeoned with a crowbar. The neighborhood is shocked.

The crime scene is surreal, her body positioned as if she’s simply sleeping. Media swarms the area.

True crime bloggers and podcasters descend, eager to sensationalize the tragedy. Douglas is arrested with the crowbar in hand and blood on his clothes.

He doesn’t speak. Everyone begins to react to the murder through their own lens.

Nick pretends to grieve while distancing himself emotionally. Jackie crumbles under guilt and scrutiny.

Adam struggles to rationalize his involvement. Cece grows suspicious of her father and distances herself emotionally, especially as she overhears gossip that links him to Jackie.

Neighbors whisper about the murder. The suburban dream begins to collapse under the weight of reality.

Douglas eventually speaks. He confesses—not in clear, rational terms, but through a raw emotional recounting of betrayal, confusion, and anger.

He doesn’t fully understand what he did or why, only that something inside him broke. The novel ends with a brief epilogue focusing on Douglas and Cece.

Douglas is in juvenile detention, quiet and remorseful, haunted by what he’s done. He clings to fading memories and begins to write, unsure of whether it brings healing.

Cece, now older, reflects on what was lost. Her memories of her mother have begun to blur.

She no longer sees her father, and her contact with Jackie is sparse and strained. She keeps fragments of her past—like the butterfly wings her mother once saved—but even these are falling apart.

There’s no dramatic resolution. Instead, the story closes on the residue of trauma—what remains when the violence is over, but the damage continues to echo.

The characters are left in a limbo of guilt, grief, and fractured identity. They struggle to move forward in a world that no longer makes sense.

Characters

Jackie Stinson

Jackie begins as an overburdened suburban mother of four, grappling with emotional isolation and the weight of domestic responsibility. Her identity has been gradually consumed by motherhood and a loveless marriage, leaving her vulnerable and desperate for acknowledgment.

Jackie’s struggle with body image and self-worth drives her to join a weight-loss group, where she finds emotional sustenance in her friendship with Theresa. This relationship gives her a sense of empowerment, but also lays the groundwork for moral collapse.

Her affair with Adam, Theresa’s husband, is a misguided grasp at validation and intimacy, which ultimately catalyzes the unraveling of both families. Following the murder, Jackie is paralyzed by guilt and shame.

She realizes too late that her pursuit of visibility and control contributed to Theresa’s death and her son’s emotional deterioration. She becomes a figure of tragic contradiction—both victim and perpetrator of suburban despair.

Theresa Linden

Theresa is portrayed as a calm, nurturing figure whose identity is deeply tied to her roles as mother and wife. Yet beneath her composed surface lies a well of emotional emptiness and unacknowledged loss—an abortion, a distant marriage, a daughter growing away from her.

Her friendship with Jackie becomes her emotional lifeline. Her participation in the weight-loss group reflects a longing to reclaim agency over her life.

Theresa is introspective, yearning for connection, and quietly aware of her fading place in her family. Her murder is the emotional and narrative fulcrum of the novel.

She is transformed from a passive figure into the center of communal grief, speculation, and guilt. In death, she becomes a mirror reflecting the dysfunction of those around her—especially the men who failed her and the women who envied her.

Her absence haunts the remainder of the story, underscoring how little she was truly seen in life.

Douglas Stinson

Douglas is the most tragic and psychologically complex character in the novel. As Jackie’s eldest son, he absorbs the silent toxicity of his home.

A mother desperate for control, a father disengaged, and a household filled with emotional neglect all leave deep marks on him. His sexual confusion, voyeurism, and growing fixation on Cece reveal a disturbed mind unable to process betrayal and desire.

Witnessing his mother’s affair with Adam becomes the breaking point. It is an emotional explosion that culminates in Theresa’s murder.

Douglas’s actions are not premeditated but erupt from a storm of pain, shame, and helplessness. After the crime, his silence in custody reflects a boy at war with himself.

By Part III, his inner monologue reveals a child slowly realizing the irreversibility of his actions. He clings to structure and reflection as a form of penance.

Douglas becomes a symbolic casualty of everything the adults around him failed to acknowledge or prevent.

Cece Linden

Cece represents the painful threshold between childhood and adulthood. Initially quiet and sensitive, she becomes increasingly aware of the dysfunction surrounding her.

She notices the unsettling behavior of Douglas, the moral decay of her father, and the emotional fragility of her mother. Cece perceives what others try to conceal.

This intuitive dread becomes a defining aspect of her character. Theresa’s death shatters Cece’s world.

Her transformation in the later chapters shows a young girl forced to mature in the wreckage of betrayal and violence. She begins to see through the illusions of family, friendship, and love.

Cece becomes more emotionally detached and introspective. Her final reflections, marked by skepticism and sorrow, indicate that while she survives, she is irrevocably changed.

Cece becomes the novel’s emotional anchor—a figure through whom the reader experiences the lingering impact of grief and the collapse of innocence.

Adam Linden

Adam is a deeply flawed and self-absorbed man. His charm masks a fundamental emotional vacancy.

While outwardly fulfilling the role of father and husband, he is disengaged and restless. His affair with Jackie is not just an act of betrayal but a reflection of his cowardice.

He chooses secrecy and fantasy over confronting the emptiness of his marriage. Adam’s inability to take responsibility for his choices haunts him in the aftermath of Theresa’s death.

Though he doesn’t wield the weapon, his actions are undeniably complicit in the events that unfold. He is consumed by guilt yet lacks the courage for atonement.

Cece’s growing fear and mistrust of him show how deeply he has eroded the very relationships that should have grounded him. By the end, Adam becomes a hollow presence.

He is a man exiled from the affections of his daughter and stripped of moral standing.

Nick Stinson

Nick, Jackie’s husband, epitomizes suburban disconnection and patriarchal entitlement. He is physically present but emotionally absent.

Nick is detached from his wife, his children, and himself. He mocks Jackie’s weight and seeks flirtations at work.

He indulges his midlife dissatisfaction through petty cruelties and passive disengagement. His inability to emotionally support his family makes him blind to Douglas’s unraveling and Jackie’s despair.

After the murder, Nick processes events selfishly. He is more annoyed by the disruption to his routine than moved by real grief.

Nick performs concern but remains fundamentally unchanged. He is a symbol of the willful ignorance and inertia that allow dysfunction to fester.

Nick’s role in the story is that of a background enabler. He doesn’t act, doesn’t listen, and doesn’t change, yet his neglect is central to the novel’s tragedy.

Nathan and Jayson Stinson

Nathan and Jayson, two of Jackie’s sons, offer childlike lenses into the chaos of their home. Nathan envies Cece’s calm life.

This envy indicates a longing for emotional stability and a recognition of his own family’s dysfunction. Jayson, more confused and passive, reflects the helplessness of children caught in emotional crossfire.

Both boys sense the strangeness in Douglas’s behavior but are too young to fully understand or intervene. Their experiences illustrate the ripple effect of adult choices on children.

They experience the silent trauma that accumulates in observation and confusion. Post-murder, they struggle to carry on.

They are burdened by grief and uncertainty, each representing the collateral damage of broken families and failed communication.

Jessica Blender and Mike Shasta

Jessica Blender and Mike Shasta are outsiders who parasitically feed on the tragedy. Jessica, a true-crime blogger, romanticizes the violence.

She turns Theresa into a narrative device for her audience. Mike, a podcaster, exploits Douglas’s mental state to craft sensational content.

Together, they represent the grotesque spectacle of media consumption. They show the way real suffering is repackaged into entertainment.

Their presence in the novel sharpens the critique of voyeurism and moral decay in contemporary culture. They reveal how easily human lives become commodities in the wake of trauma.

Themes

Domestic Disintegration

The novel explores how the structures of suburban family life can mask instability and collapse. At the center are the Stinsons and the Lindens, two families who initially appear typical—comfortable homes, children, routines.

But as the story unfolds, their domestic lives are revealed to be crumbling from within. Theresa’s devotion to motherhood becomes a source of emptiness as she begins to feel invisible inside her own home.

Jackie, overwhelmed by the demands of motherhood and mocked by her husband, seeks refuge in food and eventually in transformation through weight loss. This transformation, however, leads her into a destructive affair with Adam.

The homes on Hot Springs Drive are more than physical spaces; they are emotional arenas absorbing the stress, betrayals, and desires of those inside. The children, especially Cece and Douglas, internalize these tensions, even if they cannot fully understand them.

What begins as a friendship and shared desire for self-improvement becomes a chain of events that culminates in violence. The murder of Theresa is not a sudden rupture but the end result of years of accumulated fractures.

By the final part, the families are shattered. But that fracture merely exposes how fragmented and strained their lives had been all along.

The Consequences of Emotional Neglect

Emotional neglect runs through the novel as a subtle yet destructive force. The characters suffer not just from active harm but from being unseen, unheard, and unmet.

Theresa’s emotional life deteriorates as Cece grows up and Adam retreats into himself. Her friendship with Jackie becomes her only meaningful connection, even as that too becomes compromised.

Jackie is emotionally abandoned in her marriage. Nick reduces her to her weight and mocks her attempts at self-care, leaving her desperate for validation.

Douglas is the most tragic example of what neglect can produce. His disturbing behavior goes unnoticed until it’s too late, and his silence is misread as distance rather than a cry for help.

The murder he commits isn’t senseless rage but the result of years of emotional abandonment. He carries a storm of unprocessed feelings with nowhere to place them.

Even Cece is not spared. Her intuition tells her something is wrong long before she can articulate it, and by the end, she is emotionally isolated.

The novel shows that when families fail to connect emotionally—when silence replaces acknowledgment—tragedy becomes not just possible, but inevitable.

Suburbia and Performed Normalcy

Hot Springs Drive portrays suburbia as a place where performance takes precedence over authenticity. The neighborhood’s appearance—well-kept lawns, polite smiles, shared barbecues—conceals deep emotional voids.

The Stinsons and Lindens are emblematic of this performance. Nick sells cars and charm but is emotionally disengaged. Jackie wants to be seen as a better version of herself but is breaking inside.

Theresa creates a picture of maternal devotion, but behind it lies loneliness and loss of identity. Adam clings to a stable image while committing acts that betray everything it stands for.

When Theresa is murdered, the community reacts with disbelief, not because they cared deeply, but because it shatters the illusion they built together. The event becomes a spectacle for outsiders.

Bloggers and podcasters jump to exploit the tragedy, showing how quickly real pain becomes entertainment. The neighborhood turns inward, locking doors, avoiding each other, protecting the illusion of safety.

The novel shows that suburbia’s obsession with being “normal” creates conditions where real emotional lives are ignored. It reveals that keeping up appearances often means ignoring the signs of disaster.

The pursuit of perfection becomes a prison, and the cost of maintaining it is paid in silence, guilt, and, eventually, blood.

Adolescence and the Loss of Innocence

The novel offers a stark portrayal of adolescence as a time marked not by discovery, but by disillusionment. Cece and Douglas are central to this theme, each navigating a collapse of trust and understanding.

Cece starts as a sensitive girl curious about the world around her. But as she begins to perceive adult flaws—her father’s betrayal, her mother’s despair—she retreats inward.

She is forced to grow up quickly, learning that adults are not always safe or truthful. Her final state is one of detachment, suspicion, and emotional distance.

Douglas, by contrast, turns inward in a different way. He becomes consumed by compulsions, rage, and isolation. His experience of adolescence is chaotic and dark.

His inability to process betrayal—particularly the affair he witnesses—leads him to a horrifying act. He does not fully understand his own emotions, and that confusion turns violent.

The other Stinson children—Nathan, Jayson—are also affected. They watch their family unravel but do not have the tools to comprehend it, leaving them in a state of emotional limbo.

Adolescence in Hot Springs Drive is not a bridge to maturity but a portal into emotional wreckage. The young characters are shaped by what their parents fail to acknowledge or resolve.

Female Identity and Bodily Autonomy

Through Jackie and Theresa, the novel examines the burden placed on women to control, perfect, and sacrifice their bodies. Their identities are shaped by external judgments and internalized shame.

Jackie’s relationship to food and weight is about more than appearance. It becomes her way to feel seen in a life where she feels otherwise irrelevant.

Her weight loss gives her temporary control, but the attention it brings—especially from Adam—is double-edged. The affair becomes another way she loses herself rather than regains power.

Theresa, on the other hand, has built her self-worth around being a mother. But as Cece grows more independent and Adam grows more distant, her identity begins to slip away.

Their friendship is born out of mutual longing and shared dissatisfaction. But it cannot save them from the broader structures that diminish women’s inner lives.

The betrayal by Adam and Jackie is not just personal—it confirms Theresa’s worst fear: that she is replaceable, unseen, and discarded. Her murder is both literal and symbolic.

The novel shows that female identity in suburbia is policed by expectations of motherhood, beauty, and loyalty. When those identities are stretched or broken, the consequences are devastating.

The theme is not about redemption through transformation, but about the dangerous illusion that women can fix themselves simply by being thinner, more nurturing, or more agreeable.