How Bad Do You Want It Summary and Analysis

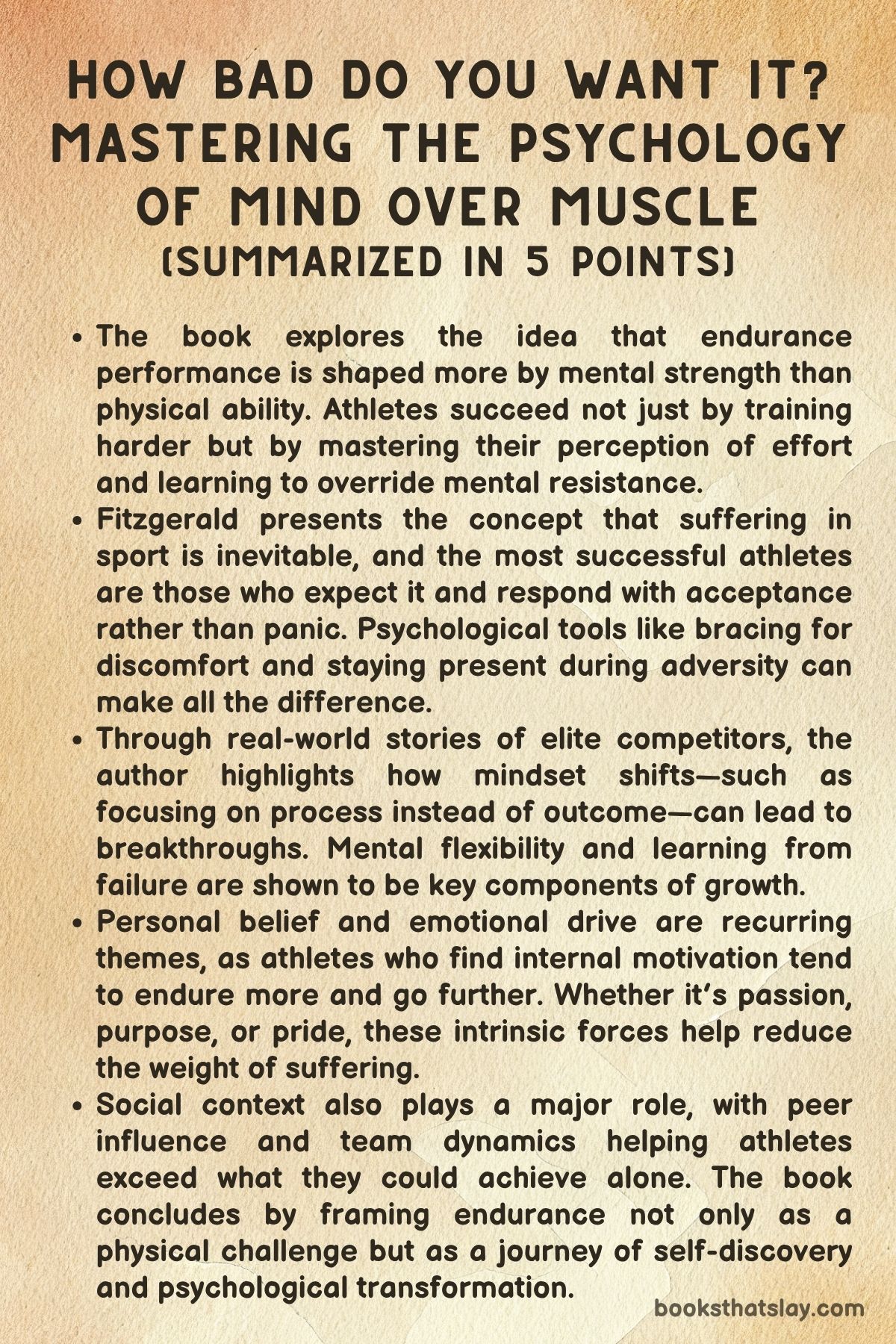

How Bad Do You Want It? by Matt Fitzgerald is an exploration of the mental side of athletic performance.

Rather than focusing on training plans or nutrition, the book emphasizes the psychological traits that distinguish good athletes from great ones. Through gripping real-life stories of endurance athletes—cyclists, runners, and triathletes—Fitzgerald unpacks the mental strategies and emotional resilience that fuel peak performance. Using the psychobiological model of endurance, he shows that perceived effort is the true limit—not the muscles or lungs.

This book is not just for athletes; it’s for anyone seeking to master discomfort, self-doubt, and adversity through mental strength.

Summary

How Bad Do You Want It? presents a series of real-world stories from elite endurance sports, each demonstrating a key psychological principle.

Matt Fitzgerald begins with the 2010 Chicago Marathon, where Sammy Wanjiru, despite poor preparation, beat a fitter opponent through sheer mental resolve.

This sets up the book’s central idea: endurance performance is limited not by physical capacity, but by how much suffering the mind is willing to accept.

The second story explores the collapse of Jenny Barringer (Simpson) at the 2009 NCAA Cross Country Championships. Expected to win, she faltered when the race didn’t go as planned.

Fitzgerald highlights how unpreparedness for discomfort can break an athlete. The takeaway: athletes must expect and embrace pain from the start, or they’ll be caught off guard.

Next, the book recounts Greg LeMond’s legendary comeback to win the 1989 Tour de France after a life-threatening injury.

His patience during recovery and unshakable belief in eventual success exemplify how psychological resilience, stretched over time, can produce remarkable outcomes.

Catriona Morrison’s story during the 2011 Ironman 70.3 shows the importance of releasing control. After a disastrous start, she stopped obsessing over her performance and instead focused on the present moment.

This shift in mindset led her to victory. Fitzgerald points out that letting go of fixed expectations can lower perceived effort and enhance performance.

Sarah Groff’s journey underscores the “workaround effect”—using mental flexibility to manage one’s weaknesses.

Rather than perfect every skill, Groff accepted her limitations and worked with them strategically.

This illustrates that resourcefulness can be more powerful than brute improvement.

Thomas Voeckler’s transformation after years of underachievement shows how failure can be converted into motivation.

By treating setbacks as feedback rather than identity-defining moments, he developed a sharper drive.

The emotional energy of frustration, when channeled correctly, becomes a competitive asset.

Paula Newby-Fraser’s near-finish collapse at the 1995 Ironman World Championship demonstrates that even champions have weaknesses.

But rather than be defeated by the experience, she used it to rebuild her approach.

This chapter stresses that recognizing and working on one’s vulnerabilities is essential for long-term growth.

Andy Potts, a latecomer to triathlon, reached elite levels by tapping into a deep internal drive.

Fitzgerald highlights how self-understanding and intrinsic motivation can sustain an athlete when external results or recognition aren’t enough.

Potts succeeded because he believed deeply in his personal mission.

Team dynamics are explored through the story of the 2013 U.S. men’s cross-country team.

They surpassed expectations by leaning into group motivation.

Training and competing with others can boost confidence, increase effort, and create a powerful shared momentum.

The presence of others can stretch individual limits.

Brent McMahon’s improvement is linked to changing his expectations.

Rather than race with fear, he began to believe he belonged at the top.

This shift elevated his pain tolerance and race-day performance.

Fitzgerald shows that what athletes expect can influence how hard they’re willing to push.

Doris Brown Heritage’s career highlights that age doesn’t limit passion.

She continued to train and win into her 40s.

Her story reflects how emotional commitment can extend athletic longevity and reduce the psychological cost of hard effort.

Passion, not age, keeps athletes in the game.

The final chapter features Siri Lindley, whose triumph over anxiety and personal trauma through sport illustrates the ultimate reward of endurance.

Her journey reveals that mental fitness isn’t just about competing—it’s about transforming one’s identity.

Suffering becomes meaningful when it leads to greater self-knowledge and strength.

Key People

Sammy Wanjiru

Sammy Wanjiru emerges as a compelling portrait of mental ferocity in the face of physical disadvantage. During the 2010 Chicago Marathon, he defeated a better-prepared rival by sheer willpower, not fitness.

His ability to override pain, self-doubt, and even rational pacing showed that mental resolve can be a greater determinant than physical readiness. Wanjiru’s character is defined by his instinctive competitiveness and raw tenacity—qualities that enabled him to dig deeper than most athletes dare.

He exemplifies Fitzgerald’s core premise: mental fitness, not just physical capacity, governs elite performance.

Jenny Barringer (Simpson)

Jenny Barringer’s experience at the 2009 NCAA Cross Country Championships paints her as a cautionary example of unpreparedness in mental expectation. Despite being a favorite, she crumbled not due to physical fatigue but due to psychological collapse when the race’s suffering exceeded her expectations.

Her story illuminates how even the most talented athletes can falter if they are not mentally braced for adversity. Barringer’s character reflects vulnerability and the often-overlooked need for emotional readiness.

She teaches that mental preparation must include an acceptance of discomfort, not avoidance of it.

Greg LeMond

Greg LeMond embodies resilience and the psychological mastery of time. After surviving a life-threatening gunshot wound, his return to win the 1989 Tour de France illustrates long-term mental toughness.

LeMond did not just recover; he patiently rebuilt himself through years of physical and emotional hardship. His strength was not only in enduring pain but in maintaining belief across a lengthy, uncertain timeline.

His character is a study in perseverance. Greatness often depends on the ability to psychologically manage long stretches of disappointment and deferred success.

Catriona Morrison

Catriona Morrison represents the power of psychological flexibility and the liberating effect of releasing control. After a disastrous beginning in a key race, she succeeded by detaching from her expectations and focusing instead on the process.

Morrison’s transformation mid-race was not physical—it was mental, as she let go of anxiety about outcomes and embraced the moment. Her character shows how relinquishing rigid goals can create the mental clarity required for victory.

Acceptance, rather than control, can elevate performance under stress.

Sarah Groff

Sarah Groff is portrayed as an athlete who turned her perceived flaws into competitive strengths. Rather than fixating on her weaknesses, such as slow swim starts, she developed smart tactical responses that played to her strengths.

Her success stemmed from adaptive thinking and self-awareness. Groff’s character demonstrates the value of working with oneself rather than against perceived limitations.

True mental fitness includes innovation and adaptability, not just raw toughness or perfection.

Thomas Voeckler

Thomas Voeckler’s career reflects the transformational potential of failure. His setbacks fueled a gritty, emotionally charged form of resolve that Fitzgerald calls “angry resolve.”

Voeckler didn’t just bounce back—he returned with a sharper focus and greater emotional intensity. His character is defined by pride, competitiveness, and a willingness to reinterpret failure as a challenge rather than defeat.

Through him, Fitzgerald underscores the idea that emotional responses to failure can either diminish or empower an athlete, depending on their mindset.

Paula Newby-Fraser

Paula Newby-Fraser is perhaps the most haunting yet illuminating figure in the book. Her dramatic collapse near the finish line of the 1995 Ironman is seared into endurance sport history.

Instead of retreating from the sport, she used the moment to reassess her psychological approach and strengthen her resilience. Newby-Fraser’s character is marked by vulnerability but also by insight.

She illustrates that embracing one’s lowest moments with openness can eventually lead to psychological evolution and even redemption.

Andy Potts

Andy Potts offers a portrait of inward-facing determination. His rise in the triathlon world wasn’t built on natural talent alone but on deep introspection and inner conviction.

Potts’ character is shaped by a steady internal compass—his self-belief gave him the strength to endure pain and persist where others faltered. He personifies the idea that external pressures pale in comparison to the power of internal motivation.

For Fitzgerald, Potts exemplifies the role of self-knowledge as a vital component of elite mental fitness.

Team USA (2013 IAAF World Cross Country Championships)

The collective character of Team USA demonstrates the energizing effect of social belonging and shared goals. While no single runner was expected to dominate, together they delivered an exceptional performance.

The team dynamic boosted individual resolve, proving that the presence of peers can enhance psychological strength. Their group identity served as a buffer against fatigue and isolation.

Fitzgerald uses them to show how community and camaraderie are often underestimated sources of mental toughness in otherwise individual sports.

Brent McMahon

Brent McMahon’s evolution highlights the crucial role of expectations in shaping performance. By recalibrating his outlook—from defensive caution to assertive confidence—he unlocked a new level of competitiveness.

His earlier struggles were not due to lack of ability but a lack of self-permission to succeed. McMahon’s transformation was primarily psychological, showcasing how belief in one’s rightful place at the top can actually help create that reality.

He reflects the broader lesson that what we expect of ourselves can become self-fulfilling, for better or worse.

Doris Brown Heritage

Doris Brown Heritage exemplifies how passion defies conventional limitations, including age. Competing at a high level well into her forties, her enduring success wasn’t fueled by physical superiority but by an unrelenting love for running.

Her emotional connection to the sport sustained her through decades of training and competition. Doris’s character is one of devotion.

She suggests that passion acts as a renewable form of psychological energy. She challenges the idea that mental and physical decline are inevitable with age, offering inspiration through sheer commitment.

Siri Lindley

Siri Lindley’s story is perhaps the most emotionally charged of all. Her triumph over anxiety, self-doubt, and a troubled past makes her a powerful symbol of psychological transformation.

Sport became her means of self-liberation, not just a path to trophies. Lindley’s mental fitness wasn’t just about racing hard; it was about reclaiming agency over her own identity.

Her character is deeply introspective and emotionally resilient. Fitzgerald uses her as the final embodiment of his thesis—that the true value of endurance sport lies in its capacity to reveal, refine, and ultimately empower the self.

Themes

Mental Endurance Over Physical Fitness

A central theme of the book is that mental strength plays a more decisive role than physical conditioning in endurance sports. While traditional training regimens emphasize aerobic capacity, muscle strength, and biomechanics, Fitzgerald argues that these factors only tell part of the story.

Through examples such as Sammy Wanjiru’s unexpected victory despite poor physical condition, the book illustrates that the limiting factor in performance is often not physical fatigue but the brain’s perception of effort. Athletes slow down not necessarily because their bodies can’t continue, but because their minds determine that the pain is too great.

This reframes endurance from being a purely physiological battle to a psychological one. Fitzgerald introduces the psychobiological model of endurance to show that it’s the athlete’s relationship with discomfort, rather than the discomfort itself, that governs performance.

Those who can tolerate higher levels of perceived effort are the ones who push boundaries and achieve greatness. This theme not only broadens the reader’s understanding of what it means to be “fit” but also offers a more empowering message.

Mental toughness is trainable, and with the right mindset, the ceiling of physical potential can be raised.

The Power of Expectations

Another significant theme is the profound influence that expectations have on athletic performance. Fitzgerald explains that when athletes brace themselves for hardship—when they expect the race to be painful, grueling, and full of psychological hurdles—they perform better.

This is not simply a matter of positive thinking, but rather a calibration of mental readiness. When an athlete enters a race with unrealistic expectations of ease or victory, the reality of struggle can feel disproportionately overwhelming, leading to emotional collapse and underperformance.

The story of Jenny Barringer illustrates this point powerfully, as her failure to prepare herself mentally for the suffering inherent in competition led to a breakdown. By contrast, athletes who expect difficulty are not surprised or demoralized by it.

This mental preparation can reduce perceived effort, making the experience feel more manageable even if the objective difficulty remains the same. The theme reinforces the idea that success is not just about capability but about mindset alignment.

When athletes train themselves to expect adversity and interpret it as normal rather than exceptional, they are more likely to persevere and excel.

Acceptance and Letting Go of Control

Fitzgerald also emphasizes the importance of psychological flexibility, especially the ability to relinquish control in high-pressure scenarios. Many athletes struggle with performance anxiety because they become too attached to specific outcomes or fear deviation from an ideal plan.

This rigidity can inhibit creativity, responsiveness, and ultimately, performance. The theme emerges clearly in the story of Catriona Morrison, who salvaged a disastrous race not by sticking rigidly to a predetermined strategy, but by letting go of her expectations and focusing on the present moment.

This mindset—often referred to as process orientation or detached focus—allows athletes to stay engaged without being emotionally hijacked by unmet expectations or external distractions. Fitzgerald portrays this shift as liberating rather than passive.

Surrendering to the moment can actually enhance control by aligning focus with what can be influenced rather than what cannot. The broader psychological insight is that control is paradoxical.

The more one tries to force an outcome, the more elusive it becomes. By letting go of the need to control everything, athletes can access a deeper, more sustainable level of engagement.

Growth Through Failure

Failure, rather than being a dead-end, is presented as a fertile ground for growth and mental fortification. The book repeatedly returns to the idea that the most accomplished athletes are not those who never fail, but those who interpret failure in a constructive way.

Rather than viewing a poor performance as a reflection of personal inadequacy, successful athletes reframe it as information: a signal pointing to areas for improvement. This theme is embodied in stories like that of Thomas Voeckler and Paula Newby-Fraser, who used high-profile disappointments to retool their strategies and come back stronger.

Fitzgerald introduces the concept of “angry resolve,” a potent motivational force that emerges when athletes channel frustration into determination. However, he is careful to draw a line between productive and destructive responses to failure.

The transformative power of failure lies not in the experience itself, but in the meaning the athlete assigns to it. When failure is understood as a challenge rather than a verdict, it becomes a catalyst for resilience, self-discovery, and ultimately, higher performance.

Self-Belief and Internal Motivation

The role of intrinsic motivation and self-belief is another recurring theme that underpins many of the athlete narratives. External validation, competition, and rewards can motivate performance, but Fitzgerald makes the case that lasting excellence comes from within.

Athletes like Andy Potts demonstrate that when performance is anchored in a deeply personal mission—something that resonates with identity and values—it becomes much more sustainable. This form of motivation is less susceptible to burnout because it is not contingent on outcomes or recognition.

Instead, it is rooted in self-knowledge and a sense of purpose. Fitzgerald argues that this inner drive enables athletes to endure more suffering and push through moments when external motivators would fail.

It’s also more empowering. When an athlete believes they are the source of their own strength, they gain agency over their progress and outcomes.

The message is clear—when athletes know who they are and why they are pursuing their goals, they become far more resilient in the face of adversity.

The Influence of Social Environment

The social dimension of endurance is explored through what Fitzgerald calls “the group effect,” the phenomenon by which athletes perform better in the presence of teammates, rivals, or an audience. The psychological boost that comes from shared purpose, mutual accountability, and competitive camaraderie is not just motivational—it’s neurological.

Studies show that effort perception decreases when athletes compete in groups, allowing them to tap into reserves of performance that might remain inaccessible when training alone. The Team USA performance in the 2013 IAAF World Cross Country Championships exemplifies how collective energy can elevate individual performance.

Fitzgerald suggests that this dynamic is more than peer pressure. It is a form of psychological scaffolding that supports endurance.

Athletes often discover new limits not in isolation, but in community. This theme expands the understanding of mental fitness to include not just individual resilience but also the capacity to draw strength from others.

It redefines toughness not as solitary grit but as relational synergy.

Passion and Longevity

Fitzgerald explores how passion serves as a sustaining force that not only initiates athletic pursuits but keeps them alive long after conventional limits would suggest decline. This theme is particularly pronounced in the story of Doris Brown Heritage, whose career defied age-based expectations.

Passion here is portrayed not as fleeting excitement but as a deeply rooted emotional commitment that replenishes motivation even in the face of exhaustion, injury, or social discouragement. Athletes who remain emotionally connected to their sport can train longer, recover more enthusiastically, and maintain competitive drive even as their bodies age.

Fitzgerald presents passion as a renewable psychological resource that decreases perceived effort and increases the willingness to suffer for the sake of something meaningful. It provides a counterweight to the physical decline that inevitably comes with age.

Performance can be sustained and even improved over time. The implication is that love for the process is just as critical as any physical attribute in determining long-term success.

The Transformational Value of Suffering

The final and perhaps most philosophical theme is the idea that the suffering inherent in endurance sports has intrinsic value beyond medals, personal bests, or recognition. Fitzgerald concludes the book with the story of Siri Lindley, whose journey through personal trauma and anxiety was transformed through the challenges of competitive sport.

Endurance becomes a metaphor for life, a structured environment where suffering is not only expected but embraced as a path to self-knowledge and transformation. The lessons learned under physical strain—emotional regulation, perseverance, humility, courage—translate into broader life skills.

For Fitzgerald, the ultimate reward of endurance sport is not winning, but becoming a better, stronger version of oneself. This theme elevates the conversation from performance to purpose.

The deepest reason to endure is not to achieve something external but to discover something internal. In this way, the book offers a powerful argument that mental fitness is not just a tool for sport—it is a framework for living.