So Late in the Day Summary, Characters and Themes

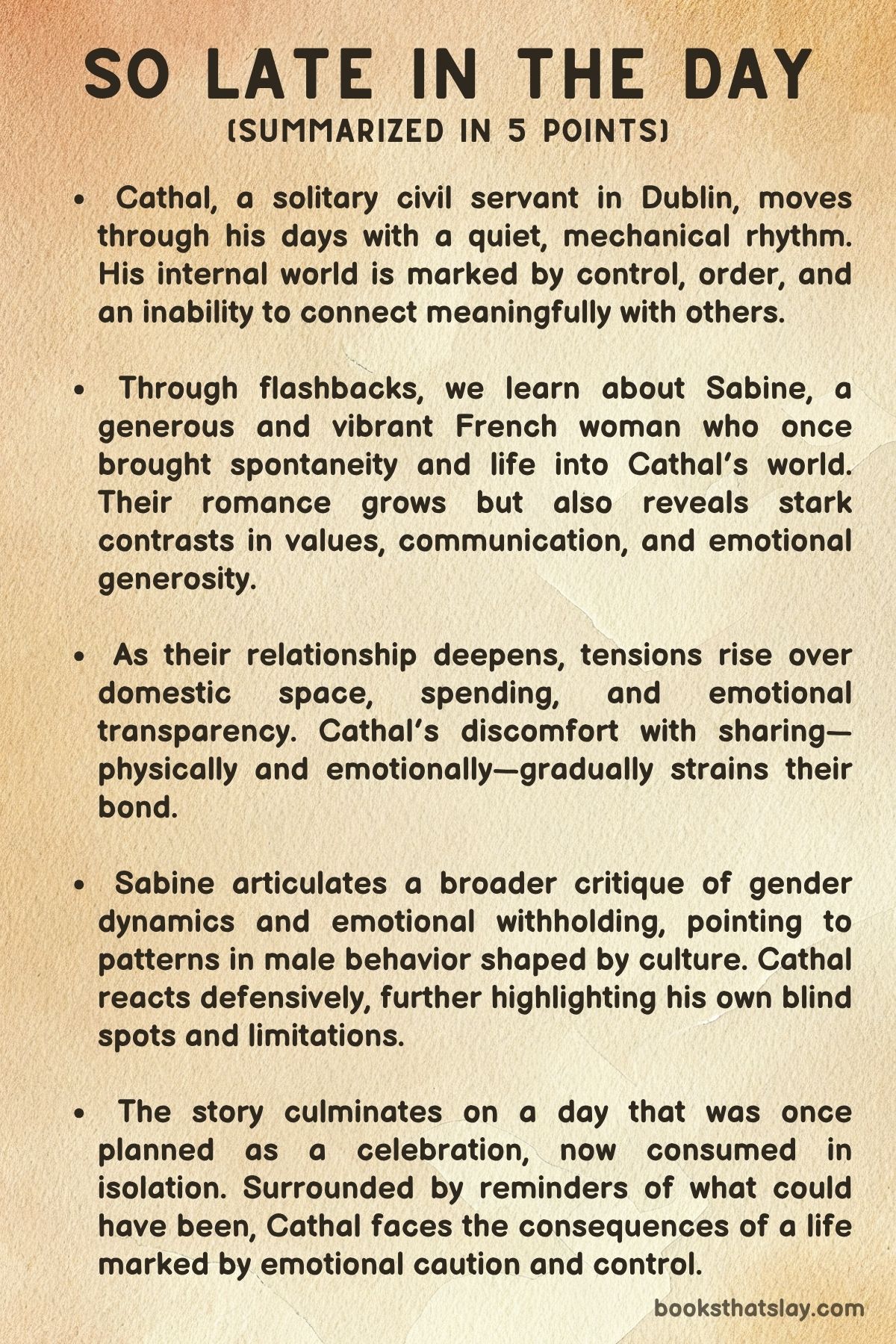

So Late in the Day: Stories of Women and Men by Claire Keegan is a compact, emotionally potent narrative that traces the slow unraveling of a romantic relationship through the lens of a single male protagonist, Cathal.

While structured in four unnamed chapters, the book reads more like a novella than a collection of separate stories. It methodically explores the psychological and emotional dynamics between men and women, particularly the destructive consequences of emotional stinginess, control, and male entitlement.

With her signature restraint and clarity, Keegan offers a powerful critique of masculine behavior and its failure to nurture, connect, or give — both emotionally and practically.

Summary

The story centers on Cathal, a solitary middle-aged civil servant living in Dublin. As the book opens, he is wrapping up his workday in the midst of a scorching summer.

His mundane routine and strained social interactions highlight his emotional withdrawal and discomfort with connection. He is resentful and inward-looking, and his encounters with coworkers or strangers are marked by impatience and irritability.

On his commute home, the presence of a cheerful fellow passenger only deepens his aversion to social warmth. A brief, sensory memory triggered by a young woman on the bus hints at a romantic past that still lingers within him.

The next section revisits that past, introducing Sabine, a French woman Cathal met at a conference in Toulouse. Their relationship had begun warmly, infused with her generosity, expressiveness, and cultured lifestyle.

She cooked meals, added color to his ordered world, and brought spontaneity that clashed with his habitual restraint. Cathal, however, remained emotionally rigid and obsessively frugal.

His disapproval of her habits — whether the number of dishes used or the cost of cherries — revealed a deeper discomfort with giving and vulnerability. When he proposed, it was clumsy and transactional, and her hesitant acceptance foretold a relationship built more on obligation than mutual understanding.

Cathal’s controlling nature soon became increasingly apparent. After Sabine moved in, her belongings disrupted the sterile neatness of his home.

Instead of embracing her presence, he viewed her domestic touches as a threat to his autonomy. Tensions escalated, and past grievances resurfaced.

A conversation with her colleague Cynthia further emphasized the cultural and gender divide between them. Cynthia’s observation — that Irish men often resist women’s independence and equate misogyny with an inability to give — haunted Sabine.

Cathal’s inability to accept such a critique, and his cold reactions, only widened the emotional chasm. Even language became a battleground, as he seized on her minor English errors to assert dominance.

A painful fight ensued, during which Cathal may have said something cruel about Sabine’s appearance. The memory is fragmented, but the damage is lasting.

He remembers it with unease, knowing it might have marked the point of no return. Sabine eventually leaves, and what remains is an emotional void marked by silence, disarray, and absence.

His once orderly home is now a shell of lost potential. Forgotten flowers on the doorstep, an untouched fridge, and the neglected cat all symbolize his detachment and loss.

The final section takes place on what was meant to be their wedding day. Cathal, alone in his house, watches a documentary about Princess Diana, drawing a silent parallel between the collapse of his own romantic aspirations and a broader narrative of female disappointment.

He drinks champagne meant for celebration and eats a flesh-toned novelty cake from his stag party — images that underscore the absurdity and sadness of his situation. A disturbing childhood memory surfaces: he once laughed when his mother was hurt in a prank by his brother.

The incident, viewed now with shame, reveals how early he absorbed a culture of cruelty masked as humor. In the closing pages, Cathal rereads a misogynistic text from his brother, but doesn’t respond.

His anger erupts when he kills a wasp with disturbing satisfaction. The act becomes a metaphor for his emotional violence: destroying what he does not understand or cannot control.

The book ends with symbols of what could have been — congratulatory cards, a hanging shirt, the engagement ring — relics of a future he was too emotionally impoverished to sustain.

It is not just the relationship that failed; it is his capacity to nurture love in any meaningful way. The loss, once external, now resides fully within him.

Characters

Cathal

Cathal is the central character whose emotional terrain the entire narrative explores. A civil servant living in Dublin, he is portrayed as a man of routine, repression, and quiet bitterness.

At first glance, Cathal appears ordinary, even forgettable, moving through the world with a kind of emotional inertia. But as the story unfolds, layers of emotional complexity emerge, revealing a man deeply at odds with himself and others.

His character is marked by a profound incapacity for emotional generosity. He is stingy—not just with money, but with affection, affirmation, and empathy.

His resistance to giving manifests in everything from his reluctance to pay a fee for resizing a ring to his inability to respond warmly to acts of care and love. Cathal’s relationship with Sabine functions as both a mirror and a magnifier for his character flaws.

Where she is open-hearted and expressive, he is guarded and judgmental. Rather than being inspired or softened by her affection, Cathal views her warmth as invasive and destabilizing.

He consistently prioritizes his comfort, control, and personal space above emotional intimacy. His tendency to reduce relationships to transactions reveals his fundamental misunderstanding of love.

This emotional poverty reaches a crescendo when, in a drunken haze, he recalls both his final blow-up with Sabine and a formative childhood incident involving his mother. Together, these moments underscore his culturally ingrained misogyny and his lifelong inability to see women as equals deserving of care.

In the final scenes, Cathal is alone, having lost Sabine not because he was unloved, but because he failed to love in return. His use of a misogynistic slur, his violent killing of a wasp, and the chilling silence of his empty home serve as metaphors for the emotional wasteland he inhabits.

Ultimately, Cathal is not an evil man but a tragically limited one. He adheres to emotional control, personal order, and latent chauvinism, resulting in the quiet collapse of his one meaningful relationship.

His tragedy is not in being abandoned, but in never having been able to fully engage with the emotional world offered to him.

Sabine

Sabine, a French woman working in the arts sector, emerges through Cathal’s recollections as a figure of warmth, generosity, and cultural vitality. She is the emotional and spiritual foil to Cathal’s cold restraint.

From her joyful cooking of a clafoutis to her open laughter and expressive manner, Sabine represents a life rooted in emotional presence and reciprocal affection. Her love is not transactional; she gives freely, hoping that such generosity will be matched, or at least received with appreciation.

Yet her kindness is often met with suspicion and misinterpretation. Cathal cannot see her gifts as acts of love but instead as threats to his autonomy or impositions on his routines.

What makes Sabine’s character especially compelling is her ability to maintain clarity amid confusion. While she may be vulnerable, especially in the face of Cathal’s emotional withdrawal, she is not naïve.

Her eventual confrontation with him about misogyny—expressed in her poignant observation that “misogyny is simply about not giving”—captures both the personal and cultural tensions that underlie their relationship. Even when her English falters, her moral clarity shines.

She calls out Cathal’s small cruelties, whether they be in tone, action, or omission, and ultimately recognizes that their emotional landscape is barren and unsustainable. Sabine is not a victim but a survivor who makes the painful decision to walk away.

Her departure is not rooted in drama or vengeance but in a quiet recognition of emotional starvation. She stands as the moral center of the story—a figure who reminds the reader that love requires openness, reciprocity, and the courage to demand more than mere compliance.

Her absence in the final chapter is felt as a void, not just in Cathal’s home but in the entire emotional atmosphere of the book.

Cynthia

Cynthia is a minor character in terms of direct presence but plays a crucial role in offering a feminist critique of the cultural landscape Cathal embodies. A colleague of Cathal’s from the accounts department, she appears in both present-day interactions and in Sabine’s recollections.

Her demeanor is warm and lighthearted, and she seems to represent a more emotionally balanced and socially aware type of Irish womanhood. One that challenges traditional male stoicism and entitlement through quiet assertion rather than confrontation.

Through Cynthia’s conversation with Sabine, the novel introduces a powerful critique of Irish masculinity. Cynthia’s observation that many Irish men are emotionally underdeveloped and resistant to women’s independence serves as a thematic fulcrum.

Her influence on Sabine is notable. She gives Sabine the language and cultural framework to articulate what she is experiencing in her relationship with Cathal.

In this way, Cynthia becomes a vehicle for the novel’s broader social commentary. She is not only a supportive presence but also a symbolic challenge to the emotional immaturity and covert misogyny that pervade the story.

Cynthia may not undergo personal change within the narrative, but her perspective catalyzes a shift in Sabine. She indirectly exposes the reader to the story’s gendered subtext.

Her role, while peripheral in terms of plot, is central to the book’s thematic depth. She highlights how seemingly incidental characters can carry profound narrative weight.

Themes

Emotional Withholding and the Economics of Love

A central theme in the book is emotional withholding, particularly as it manifests through control and frugality. Cathal’s inability to give — emotionally, materially, and psychologically — emerges as his defining character trait.

From the earliest scenes, he performs his duties and engages with others through a cold, transactional lens. Whether printing rejection letters at work or begrudging the cost of cherries his fiancée selects for a tart, Cathal views interactions through the prism of what is owed, what is spent, and what is taken.

His romantic relationship with Sabine reveals the extent of his emotional poverty. While she approaches love as something to be shared, full of warmth, spontaneity, and generosity, Cathal counts the cost of everything — not just in euros, but in autonomy and emotional exposure.

His failure to appreciate gestures of care unless they align with his rigid expectations ultimately leads to his emotional isolation. Even his proposal is clouded by this stinginess, both literal and symbolic.

His rejection of paying to resize the engagement ring encapsulates the deeper tension: for Cathal, love becomes a form of debt or contract, not a shared experience. The theme highlights the tragedy that love cannot thrive in an atmosphere of constant calculation.

Claire Keegan suggests that true affection requires an ability to give freely and without condition, something Cathal is never able to do. This inability transforms him from a mere flawed partner into a deeply alienated man whose emotional restraint becomes a form of self-inflicted punishment.

His bitterness is not just the result of being abandoned but stems from never having learned how to be generous — with his emotions, his space, or his heart.

Misogyny as the Denial of Generosity

The novel presents misogyny not as an overt form of hatred but as a subtler, insidious force expressed through the refusal to give. Sabine’s comment that “misogyny is simply about not giving” becomes the philosophical anchor of the book’s critique of gender relations.

Cathal’s actions exemplify this idea. He withholds affection, time, attention, space, and even empathy.

His frugality with love mirrors his discomfort with Sabine’s independence and emotional fluency. He is not physically violent or explicitly cruel, but his emotional withholding operates as a form of quiet domination.

Keegan uses this framework to expose how certain forms of male entitlement are normalized in everyday life. Whether in the way Cathal controls domestic spaces or in how he corrects Sabine’s language rather than respond to her feelings, these gestures accumulate.

They build a portrait of masculinity that is emotionally cowardly and possessive. Importantly, Cathal is not a cartoonish villain; he is painfully ordinary.

This normalcy is what makes his behavior chilling. Misogyny, in this context, is not about grand statements but the daily grind of not giving — of seeing a partner’s needs as burdens, of measuring love through obligation, of fearing vulnerability.

The novel critiques not only Cathal but also the culture that enables such men to flourish. It allows them to see themselves as rational while dismissing generosity as weakness.

The text challenges the reader to understand misogyny not just in terms of overt abuse but in the quieter refusal to emotionally nourish, to share, to be changed by love.

The Failure of Intimacy and the Fear of Vulnerability

Another prominent theme in the book is the failure of intimacy rooted in a fear of vulnerability. Cathal’s emotional landscape is shaped by an intense need to protect himself from exposure.

This need governs his relationships, his habits, and even his reactions to the simplest expressions of closeness. His relationship with Sabine begins with promise but quickly unravels as her attempts to deepen emotional connection are met with detachment and passive resistance.

Whether it’s his discomfort with the clutter of her belongings in his home or his unease with shared routines, Cathal is persistently averse to letting another person fully inhabit his world. Even his proposal is devoid of emotional intimacy, offered as a practical step rather than a heartfelt expression.

The novel makes clear that intimacy requires more than proximity or routine — it demands openness, a willingness to share one’s internal life, to risk hurt in order to gain connection. Cathal fails at this at every turn.

His silences, corrections, and evasions speak volumes. They reveal a man afraid not just of being hurt, but of being seen.

The novel quietly shows how this fear corrodes the foundation of his romantic relationship. Sabine, who tries to build a life with warmth and emotional honesty, becomes more alien to him the more she tries to connect.

Cathal’s retreat into solitude is not just a response to heartbreak but a return to emotional safety. It is a place where no one can challenge his authority or require his vulnerability.

The tragedy lies in how he confuses control with strength. In doing so, he loses the very thing he most likely yearns for but cannot admit to needing.

Regret and the Ghosts of the Unlived Life

The emotional arc of the book is steeped in the theme of regret. It is the kind that comes not from a single decision but from a lifetime of avoidance and emotional negligence.

Cathal is not portrayed as someone who acts maliciously, but rather as someone who fails to act — who fails to love fully, fails to accept affection, and fails to be present in his own life.

His moments of reflection, especially on what would have been his wedding day, are saturated with the weight of what might have been. The unused engagement ring, the congratulatory cards that will never be opened, the wedding shirt hanging limply in his home — these objects serve not merely as remnants of a failed relationship but as emblems of a life that he never allowed himself to live.

His is a world where choices are not seized but postponed indefinitely. Emotional safety is prioritized so thoroughly that joy is sacrificed.

Even his binge on the wedding cake and champagne, instead of being celebratory, underscores a grotesque parody of the life he lost. These rituals, performed in solitude, are both pathetic and heartbreaking.

They dramatize how regret can accumulate through a thousand tiny denials rather than a single catastrophic error. Keegan shows that regret, especially the regret born of withholding and self-protection, is not just sorrow for what happened but anguish for what was never even attempted.

Cathal is haunted not just by the memory of Sabine but by the version of himself he refused to become.

The Legacy of Cultural and Familial Conditioning

Beneath the individual story of Cathal lies a broader commentary on the cultural and familial forces that shape male behavior. The childhood flashback involving Cathal’s mother falling from a chair as a result of a cruel prank played by his brother is revealing.

The laughter of the male figures in the room, including a young Cathal, is not just an isolated memory but a foundational moment. It signals an early lesson in gendered power dynamics and emotional indifference.

The women are the butt of the joke, the men the ones who laugh and bond through shared callousness. This moment becomes a microcosm of a cultural tradition that treats male insensitivity not as a flaw but as a rite of passage.

Cathal’s emotional rigidity, then, is not merely personal but inherited. His failure to give, to care, to make space for someone like Sabine is the end result of years of silent conditioning.

He is not so much uniquely cruel as he is a product of a system that values stoicism over softness, control over collaboration, and pride over vulnerability. Keegan’s narrative suggests that until these early scripts are rewritten, such failures of intimacy will persist.

Until men are allowed, even encouraged, to embrace emotional intelligence, the emotional impoverishment seen in Cathal will continue. The novel is not only a portrait of one man’s emotional demise but also an indictment of the silent legacies that lead men to equate love with possession and generosity with loss of power.