The Ball at Versailles Summary, Characters and Themes

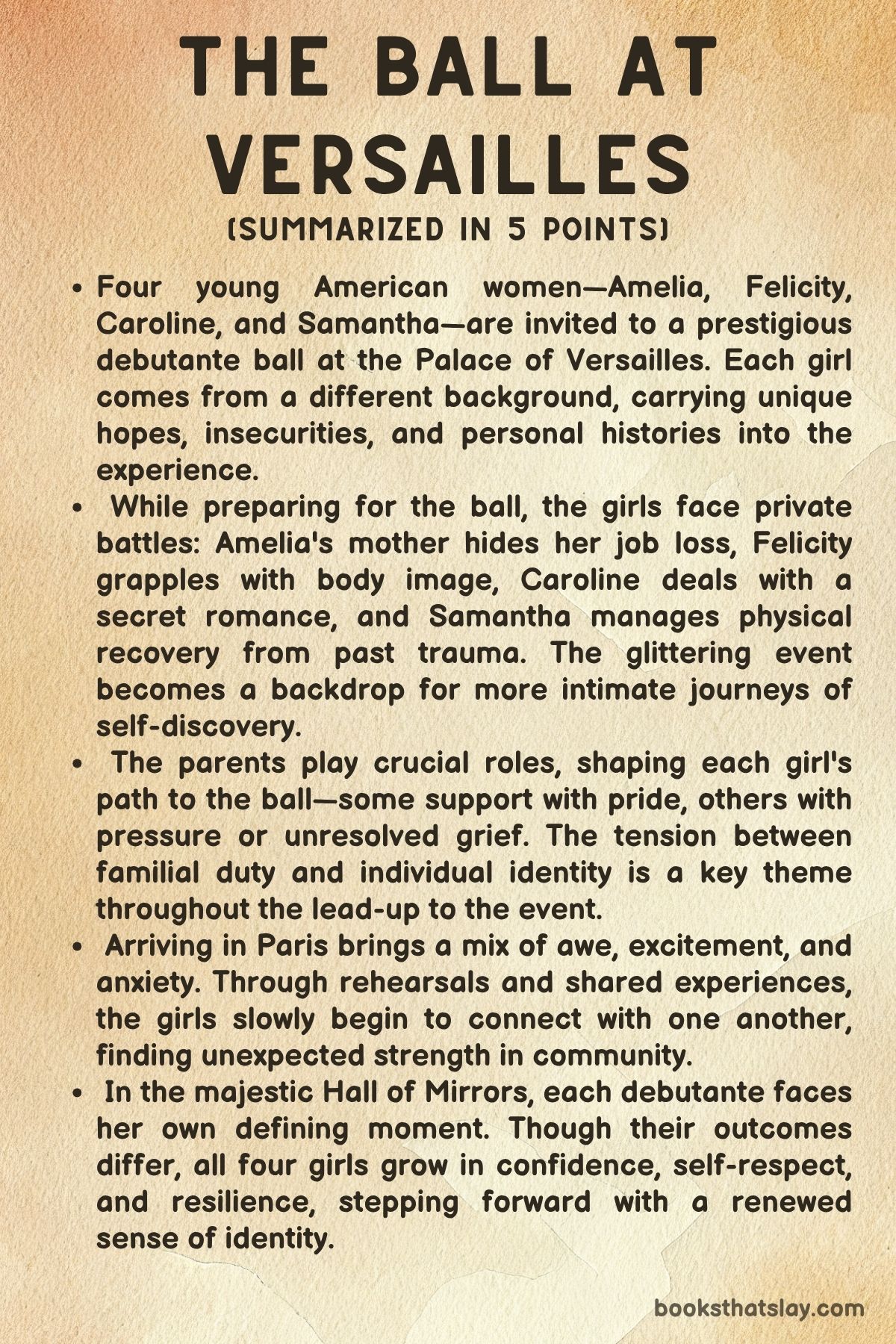

The Ball at Versailles by Danielle Steel is a moving and atmospheric novel that centers around four young American women from vastly different backgrounds. They are invited to one of the most prestigious social events in the world—the international debutante ball at the Palace of Versailles.

Set in the 1950s, the novel explores themes of identity, aspiration, transformation, and emotional healing. Each girl brings her own burdens, dreams, and fears to the grand occasion.

What unfolds is a compelling portrayal of growth, resilience, and unexpected kinship. The event becomes more than just a rite of passage; it serves as a quiet revolution in their lives.

Summary

The story follows four young women—Amelia, Felicity, Caroline, and Samantha—who are invited to attend the exclusive debutante ball held at the Palace of Versailles in France. Each of them comes from a different corner of America and brings with her a unique emotional and social landscape.

Amelia Fairbanks Alexander is a studious and principled college student from New York. She is raised by her widowed mother, Jane, who works in publishing.

The invitation to the ball represents a window into a world Amelia doesn’t believe in—one filled with privilege and ceremony. Although skeptical about the purpose of such a tradition, Amelia agrees to attend, more to please her mother than for personal ambition.

Jane quietly deals with the trauma of losing her job just before the trip. She pours all her energy into making the experience unforgettable for Amelia, shielding her daughter from the harsh new reality they might soon face.

In Texas, Felicity Smith, the brainy and socially awkward daughter of oil barons, is mortified by the idea of being presented to high society. Her parents, especially her image-conscious mother, Charlene, view the ball as a chance for Felicity to emerge from the shadow of her stunning older sister and redefine herself.

Although Felicity initially resists, she ultimately agrees to go. She is driven by a complicated mix of familial loyalty and curiosity.

Beneath her insecurities, Felicity begins to envision that perhaps she, too, belongs in a world that has always seemed closed off. Her journey is filled with self-doubt, but also possibility.

Caroline Taylor is a poised, confident teenager from Los Angeles and the daughter of two famous movie stars. She appears to have everything: beauty, fame, and elegance.

Behind her polished exterior lies a turbulent emotional world. She is deeply involved in a secret affair with a much older actor, Adam, which creates tension as she prepares to leave for Paris.

Caroline is both excited by the ball’s promise of glamour and burdened by doubts about her relationship. Her participation becomes less about being seen by others and more about seeing herself clearly for the first time.

Samantha Walker, another New Yorker, has lived a secluded life after surviving a car crash that claimed her mother and brother. She has physical challenges and emotional scars that make social settings daunting.

Her protective father, Robert, is reluctant to let her go but ultimately allows it. He hopes she will find confidence and independence.

For Samantha, the ball is more than a dance. It’s a quiet declaration of her strength and ability to reenter a world she’s long kept at arm’s length.

As the girls prepare, the story follows their emotional journeys and evolving relationships with their families. Amelia grapples with her mother’s hidden financial distress.

Felicity struggles with her self-image and embarks on a quiet transformation. Caroline experiences heartbreak when she realizes her lover may never fully choose her.

Samantha battles her fear of public scrutiny, determined to walk and dance despite the odds. Each young woman is pushed to her emotional limits in different ways.

When they finally arrive in Paris, the tension and anticipation are palpable. The city stirs different emotions in each of them—excitement, anxiety, and hope.

As they attend rehearsals and events leading up to the ball, the four girls slowly form an unlikely bond. Shared nerves and small acts of empathy help bridge their differences.

The climax of the story unfolds in the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles. Each young woman steps into the spotlight and leaves behind the girl she once was.

Amelia shines with quiet strength. Felicity surprises everyone with her newfound confidence.

Caroline chooses to move on from heartbreak. Samantha finds joy in movement she once feared.

The Ball at Versailles ends on a note of transformation. Not through grand gestures, but through quiet personal revelations.

Each girl, in her own way, becomes someone stronger, more self-aware, and ready to face the future beyond the gilded halls of Versailles.

Characters

Amelia Alexander

Amelia begins as a strong-willed, intellectually inclined young woman shaped by the hardships her mother endured as a widowed single parent. A Barnard College student, she initially resists the concept of the Versailles ball, viewing it as an elitist relic of another era.

Her skepticism reflects her progressive worldview, as she champions social justice and education over status or glamour. Yet, beneath this rational veneer is a young woman curious about the world and uncertain about her place in it.

Amelia’s journey to Paris, and her ultimate participation in the ball, is not so much a transformation as it is an expansion of her identity. She learns to embrace beauty and tradition without surrendering her values.

Her poised debut at the ball underscores a quiet evolution. Amelia emerges more confident, more open, and more understanding of the coexistence of privilege and purpose.

Jane Fairbanks Alexander

Jane, Amelia’s mother, is a woman of grace and strength forged in the aftermath of loss. Widowed during World War II and forced to rebuild her life while raising a daughter, she finds purpose in her editorial career and motherhood.

Jane’s narrative arc revolves around her dedication to Amelia’s future—even sacrificing her financial security when she loses her job, a fact she keeps hidden from her daughter. Jane embodies quiet perseverance, masking her suffering beneath elegance and resolve.

Her encouragement of Amelia to attend the ball is both an act of love and hope. She yearns to give her daughter a chance at happiness and connection that life denied her.

In Jane, we see a portrait of maternal courage. She is someone whose dignity persists in the face of professional and personal upheaval.

Felicity Smith

Felicity undergoes perhaps the most visible transformation in the novel. Introduced as an awkward, self-conscious young woman overshadowed by a conventionally attractive and socially adept sister, Felicity is a reluctant participant in the ball.

Her intelligence and bookish nature set her apart in a Texas oil family that prizes social optics. Her mother, Charlene, pressures her into attending, seeing it as a social stepping-stone.

What follows is a slow but steady journey of self-acceptance. Felicity, initially burdened by weight issues and insecurities, begins to take charge of her appearance and demeanor—not out of vanity, but as an assertion of agency.

By the time she steps into the Hall of Mirrors in a navy gown, she is radiant not only in appearance but in the quiet strength of character that impresses those around her. Her story is one of claiming space and dignity in a world that had previously marginalized her.

Charlene Smith

Charlene is a quintessential Southern matriarch—domineering, status-conscious, and determined to shape her daughters into society’s ideal. She is hard on Felicity not out of malice, but because she believes conformity is the surest route to success and happiness.

Charlene’s character reveals the generational tensions at play. Her worldview is rigid and deeply rooted in appearances, but she also wants the best for her daughter, even if she doesn’t know how to express it lovingly.

As Felicity blossoms, Charlene is both surprised and quietly proud. Perhaps she recognizes, even if fleetingly, that true beauty lies in confidence and authenticity.

Caroline Taylor

Caroline’s life in Hollywood is glamorous on the surface but emotionally chaotic beneath. The daughter of movie stars, she lives in a world of illusion and scrutiny.

Her relationship with a much older man, Adam Black, becomes the central conflict in her storyline. It highlights her vulnerability and longing for stability.

Despite her beauty and poise, Caroline is emotionally raw and searching. Her journey to Paris is less about societal debut and more about reclaiming emotional autonomy.

The ball becomes a crucible in which she finally acknowledges Adam’s neglect and decides to let go. In doing so, she evolves from a girl clinging to a fantasy to a young woman owning her emotional narrative.

Her radiance at Versailles is not just due to her appearance. It stems from a painful but liberating reckoning with heartbreak.

Samantha Walker

Samantha’s character is defined by resilience and quiet bravery. Physically limited by a childhood accident that killed her mother and brother, she lives under the protective shadow of her father, Robert.

Her decision to attend the ball is a declaration of independence. While she is initially fearful—of falling, of being seen as weak—she slowly prepares herself, both mentally and physically, to meet the moment.

Her triumph is not just in attending but in dancing without pain. This act is symbolic of liberation.

Samantha does not simply seek a moment of inclusion. She claims her right to joy and self-expression.

Her silver gown and radiant smile at the ball represent the grace that comes from healing. They also show the courage it takes to risk visibility.

Robert Walker

Robert is a deeply sympathetic figure—a grieving widower devoted to his daughter’s well-being. His protectiveness of Samantha is born from love but borders on over-cautiousness.

Over the course of the narrative, he learns to let go. He begins to trust Samantha’s strength and judgment.

His quiet moments—secretly shopping for her gown, watching her prepare—reveal a man caught between love and fear. Robert’s growth mirrors that of his daughter.

He, too, must face the pain of the past to allow space for the future. His support during the ball, watching Samantha dance, marks the emotional climax of his journey.

Araminta Smith

Though not one of the core protagonists, Araminta plays a vital role in shaping Felicity’s early self-doubt. She represents the cruel side of societal expectations—beautiful, confident, and dismissive of those who don’t fit the mold.

Her jealousy as Felicity begins to shine underscores her own insecurity. Araminta is less a villain and more a reflection of the toxic standards that Felicity overcomes.

Her presence adds tension but also amplifies Felicity’s triumph. She highlights the contrast between superficial beauty and authentic self-worth.

Themes

Identity and Transformation

A central theme that runs through the entire novel is the search for identity and the personal transformation that results from stepping out of familiar contexts. Each of the four girls—Amelia, Felicity, Caroline, and Samantha—enters the experience of the Versailles ball with a firm but evolving sense of who they are.

The journey from their homes to Paris becomes a mirror for their internal evolution. Amelia wrestles with her progressive ideals in contrast to the aristocratic traditions of the ball, gradually learning to reconcile her values with the personal meaning the event brings to her life.

Felicity, often dismissed by others and herself as an outsider in a world of physical beauty and social charm, slowly uncovers an unexpected confidence rooted in intellect and kindness. Her transformation is perhaps the most visible, as she goes from self-loathing to someone capable of owning the spotlight without changing who she truly is.

Caroline, on the other hand, confronts the reality of her seemingly glamorous life and the disillusionment that comes from a toxic romantic entanglement. Her identity as a confident Hollywood starlet is shaken, forcing her to redefine her strength not in beauty or fame, but in self-respect and independence.

Samantha’s evolution lies in reclaiming her body and her spirit after trauma. Her journey to the ball becomes symbolic of her refusal to be defined by her past, culminating in the joyous realization that she can still participate fully in life.

In all cases, the ball serves as a crucible where the girls’ identities are tested, reshaped, and affirmed—not by society’s gaze, but through inner conviction.

Motherhood and Fatherhood

The parental figures in the novel are not mere background characters but are deeply involved in the emotional arcs of the protagonists. The nature of parenthood is a major theme in The Ball at Versailles.

Jane’s quiet perseverance as a widowed mother illustrates the depth of maternal sacrifice. She shields Amelia from financial hardship and professional disappointment, prioritizing her daughter’s future even when her own stability is threatened.

This dynamic highlights the tension between parental support and the silent burdens that often accompany it. Felicity’s parents show a more complex picture.

Her mother Charlene is overbearing and obsessed with appearances, yet her intentions are rooted in a desire for Felicity to experience confidence and social acceptance. There is love beneath the pressure, though it is often misdirected.

Felicity’s father offers quieter support, serving as an emotional anchor amidst the chaos of expectations. Caroline’s relationship with her parents exposes the distance fame and privilege can create.

Though they are not abusive, their detachment from Caroline’s emotional world leads her to seek love in the wrong places. Samantha’s bond with her father Robert is deeply poignant.

His protectiveness stems from love and fear—he has already lost so much and dreads letting go of the daughter he has tried so hard to protect. Each of these parental figures, in their strengths and flaws, shapes the emotional landscape of the story.

Their decisions influence the girls’ choices and sense of self. This reveals that coming of age is not only about the child growing up, but also about parents learning to let go and trust the people their children are becoming.

Class, Privilege, and Social Expectations

The ball at Versailles is more than a social event—it is an emblem of privilege, class, and entrenched tradition. The novel interrogates these dynamics through the diverse backgrounds of its main characters.

Amelia, hailing from an educated but financially modest household, represents the intellectual elite. Her discomfort with the ball stems from its apparent celebration of outdated aristocracy.

Her presence at Versailles challenges the notion that worth is tied to wealth or lineage. Felicity, though immensely wealthy, stands outside the traditional beauty and social mold expected at such events.

Her struggle is not financial but social, as she resists being molded into something she is not. Caroline epitomizes the intersection of wealth, fame, and power.

But her internal discontent highlights the hollowness of social admiration when not grounded in authentic connection. Samantha, meanwhile, occupies a space where immense wealth is coupled with deep personal tragedy.

Her appearance at the ball underscores a reclaiming of agency within a world that often equates physical perfection with value. The ball becomes a stage where societal expectations collide with individual identity.

Each girl must determine whether to conform, reject, or redefine those expectations. Through these narratives, the novel critiques the rigid structures of class and the often-unseen costs of maintaining appearances.

Yet it also acknowledges that such events, while flawed, can serve as platforms for visibility, self-discovery, and quiet rebellion.

Feminine Empowerment and Agency

The novel is a coming-of-age story set against a backdrop that is traditionally viewed as a display of feminine subservience. Yet The Ball at Versailles subverts this expectation by portraying the ball as a transformative experience of empowerment.

The protagonists are not passive participants. They actively choose how to present themselves, how to engage with the moment, and how to define their femininity.

Amelia’s empowerment lies in her intellectual independence and refusal to be trivialized. Felicity’s strength grows through self-acceptance and quiet confidence.

She proves that being seen is not about changing oneself, but embracing one’s authentic self. Caroline makes the difficult choice to walk away from an emotionally unavailable partner.

This symbolizes a shift from dependency to autonomy. Samantha finds power in vulnerability and in her courage to step into the public eye despite physical limitations.

The ball, though rooted in tradition, becomes a site of personal assertion for each young woman. Their gowns, curtsies, and dances are not acts of submission but expressions of agency.

The narrative ultimately suggests that femininity and empowerment are not mutually exclusive. It is possible to be elegant, poised, and powerful at the same time—so long as the choice is truly one’s own.