The Fund by Rob Copeland Summary, Characters and Themes

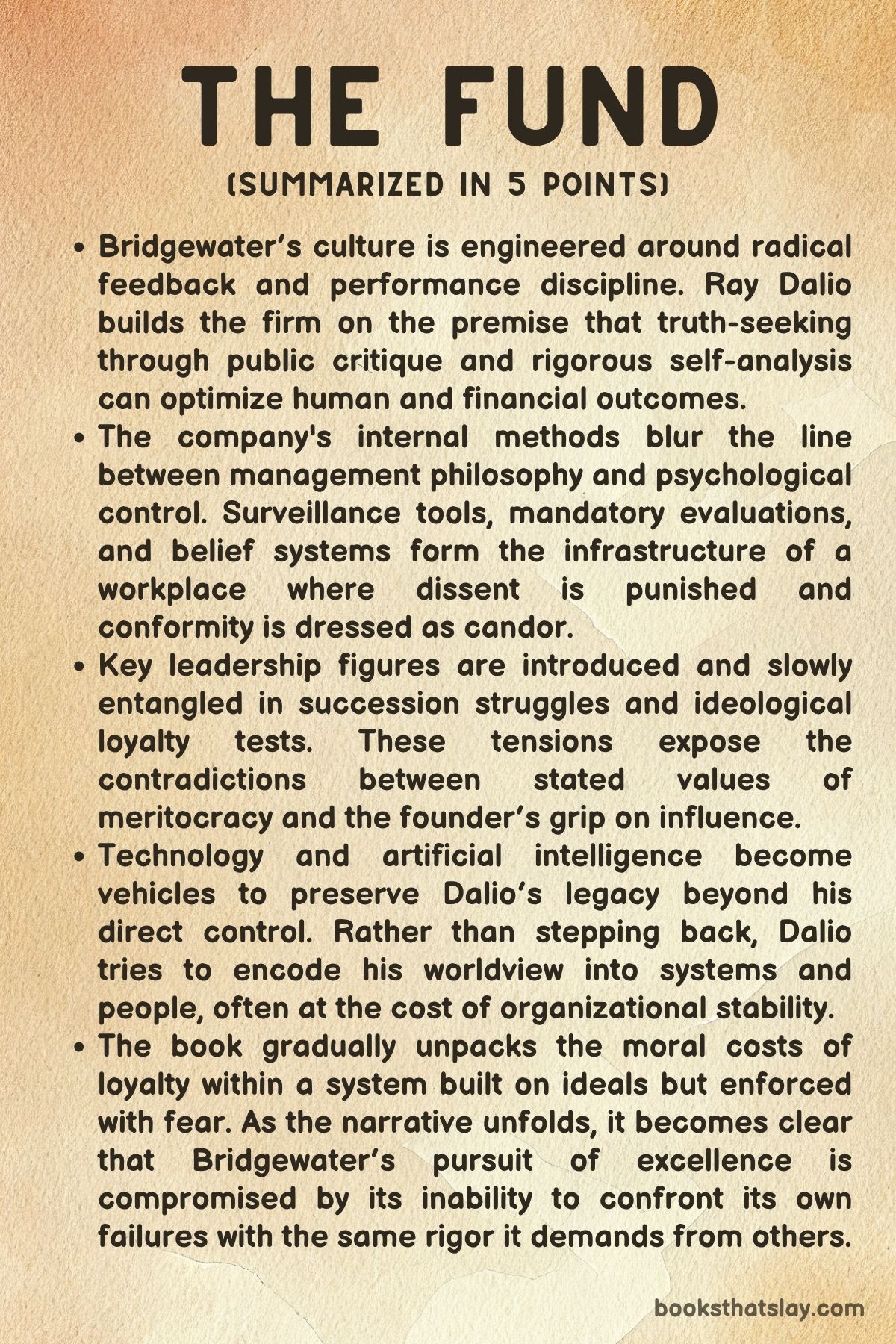

The Fund by Rob Copeland is a deeply reported exposé of Bridgewater Associates, the world’s largest hedge fund, and its enigmatic founder, Ray Dalio. Copeland, a veteran Wall Street journalist, peels back the curtain on an organization that portrays itself as a beacon of radical truth and transparency.

He reveals a culture far more complex, secretive, and, at times, disturbing than its public narrative suggests. Through interviews, insider accounts, and internal documents, the book traces the rise of Bridgewater from a small trading firm to a corporate cult driven by rigid ideology, intense surveillance, and one man’s obsession with building a perfect system.

Summary

Rob Copeland’s The Fund charts the evolution of Bridgewater Associates, beginning with the unusual philosophy behind its success and ending with its internal contradictions and moral unraveling. At the heart of the narrative is Ray Dalio, a billionaire investor who attempts to engineer not just a hedge fund, but a living organism built around his personal beliefs.

The early sections of the book introduce Bridgewater as a place unlike any other on Wall Street. Employees are expected to provide constant feedback, record meetings, and adhere to a system of “radical truth” and “radical transparency.”

Dalio envisions the firm as a machine—something that should function with minimal human error and maximum predictability. To this end, he develops systems such as the Dot Collector and enforces a feedback-heavy culture that rewards brutal honesty.

The book explores how this ideology takes hold, both in small ways—like peer-to-peer ratings—and in broader, structural transformations. The leadership is presented as a mix of true believers and wary participants.

Individuals like Greg Jensen and David McCormick rise in prominence, each trying to fit into Dalio’s vision while managing their own ambitions. Yet the firm’s culture starts to show signs of strain.

Even highly principled outsiders, like James Comey, are ultimately alienated by what they perceive as performative truth-seeking and internal politics. Meetings are recorded, employees are interrogated in public forums, and mistakes become public spectacles.

Far from fostering openness, the environment grows more oppressive and isolating. As Bridgewater gains financial clout, so too does its desire to manage its public image.

Instead of responding to criticism with openness, it becomes defensive and combative. The firm hires media specialists to control narratives, demands edits to interviews, and accuses detractors of lacking the courage to confront difficult truths.

Copeland suggests this defensiveness contradicts the very values Dalio claims to champion. While the firm claims to be a truth factory, many employees describe it as a surveillance state.

The book intensifies when personal scandals and ethical lapses are exposed. Cases of sexual misconduct, power abuse, and forced confessions suggest a culture that punishes those who stray from the company line.

Internal investigations are unevenly handled, with loyalty to the ideology taking precedence over justice or compassion. Dalio’s efforts to solidify his legacy take on an increasingly surreal tone.

He begins working with AI experts to encode his principles into algorithms that can evaluate employee behavior. The goal appears to be the creation of a digital oracle that reflects his thinking.

Dalio’s departure from day-to-day leadership is not straightforward. Although he announces a transition, he continues to influence the firm through informal networks and new governance structures.

One such structure is “The Partnership,” which effectively preserves his ideological control. Former allies are pushed out, and dissenters find themselves marginalized or dismissed.

The idea that Bridgewater is a meritocracy is shown to be flawed. Dalio’s preferences and personal influence override the very rules he put in place.

In its closing chapters, The Fund reflects on the human cost of Dalio’s experiment. Employees who once saw the firm as a place for intellectual growth come to view it as emotionally punishing.

Loyalty is rewarded only until it becomes inconvenient. Copeland argues that Dalio, in trying to eliminate bias and emotion, created a system that became just as biased and emotional—but in a hidden, institutionalized way.

The dream of a utopian workplace based on truth and rationality becomes instead a cautionary tale about ideology, ego, and control. By the end, Copeland leaves no heroes standing.

Bridgewater’s systems endure, but the sincerity that once gave them weight has faded. Dalio’s vision survives in structure, but not in spirit.

The book ultimately presents The Fund not just as a financial story, but as a study in how ideals can become instruments of power when unchecked.

Characters

Ray Dalio

Ray Dalio is the founder and philosophical architect of Bridgewater Associates. He stands at the epicenter of the book’s narrative.

Presented as both visionary and zealot, Dalio is obsessed with eliminating human error from decision-making. He strives to create a workplace that operates as a logical “machine.”

His belief system, embodied in the company’s infamous “Principles,” demands radical transparency, unfiltered feedback, and complete intellectual obedience. Yet Copeland paints a portrait of a man who, despite preaching the supremacy of reason, exercises deeply personal control over his empire.

Dalio’s identity is inseparable from Bridgewater’s DNA. His influence permeates everything—from hiring policies to software that scores employee behavior.

Despite the mathematical and algorithmic façade, Dalio is driven by emotion, pride, and fear of irrelevance. His need to remain central, even while supposedly stepping back, reveals an inherent contradiction.

He wants to automate truth, but only if truth aligns with his own worldview. This tension makes him both an inspiring reformer and an oppressive ruler.

Missy

Missy emerges as a deeply loyal yet ultimately tragic figure in the inner sanctum of Bridgewater. Initially one of Ray Dalio’s most trusted confidantes, she is a figure of devotion, discipline, and administrative might.

Her loyalty to Dalio’s ideology is profound. But her character is also marked by subtle inner conflict.

As she executes the firm’s draconian systems of accountability and behavioral engineering, she begins to experience the toll such absolutism takes on individuals—including herself. Missy represents a class of insiders who enforce the rules until those very rules turn against them.

Her eventual marginalization reflects the precariousness of favor in Bridgewater’s power structure. Even those most loyal to the system are expendable if they falter or deviate.

Her story sets the tone for the recurring theme of trusted inner-circle members being consumed by the very ideology they helped to uphold.

The Viking

Known only by his nickname, “The Viking,” this character functions as the cultural enforcer of Bridgewater’s ideals. He is a towering, intimidating presence whose role is to uphold discipline and root out weakness within the organization.

More than just a manager, he embodies the ethos of “radical truth” with a religious fervor. He appears to relish his role in challenging others.

He becomes a proxy for Dalio’s authority, wielding it often with blunt force, both metaphorically and literally in his interpersonal style. Despite his apparent belief in the system, the Viking’s rigidity makes him a controversial figure internally.

He is respected by some, feared or resented by others. His narrative arc illustrates the cost of upholding Bridgewater’s uncompromising culture.

His very nickname speaks to the martial, unyielding spirit Bridgewater valorizes. It also reveals how the firm dehumanizes people through archetypal roles.

Greg Jensen

Though more prominent in later parts of the book, Greg Jensen begins to appear as one of the heirs apparent to Ray Dalio’s empire. He is a brilliant mind with deep belief in Dalio’s philosophy.

Jensen is portrayed as both a protégé and a potential usurper. He aligns with the ideological tenets of Bridgewater but is caught in the impossible task of leading within a structure where real power remains centralized in Dalio.

His arc becomes increasingly fraught as he attempts to assert leadership while staying within the bounds of Dalio’s expectations. In Part I, his presence looms in the background.

It is already clear that he is being groomed for a higher role—a role he may not ultimately be able to control. Jensen’s development reflects the fundamental instability of a succession plan based more on philosophical purity than practical leadership readiness.

David McCormick

David McCormick, like Jensen, is another of Dalio’s chosen successors. He brings a different energy to the firm.

More traditionally corporate and less ideologically rigid, McCormick attempts to balance respect for Bridgewater’s culture with a more grounded, pragmatic leadership style. He contrasts with Jensen in that he is less a disciple and more a capable manager.

In Part I, McCormick’s presence is subtle but important. He begins to navigate the toxic blend of ideology, surveillance, and performance pressure with a level of political savvy.

Over time, McCormick becomes a symbol of the struggle between institutional continuity and personal autonomy within Bridgewater’s upper ranks. His arc underscores the difficulty of inheriting a system so tightly bound to one man’s identity.

James Comey

Though his full storyline appears in Part II, James Comey’s character arc begins to take shape in Part I. He arrives as a highly credentialed outsider attempting to integrate into Bridgewater.

His trajectory is illuminating because it exposes the cultural collision between Dalio’s ideology and real-world ethical frameworks. Comey, with his background in law and public service, approaches Bridgewater’s system with cautious curiosity.

He soon begins to clash with its dogmas. His discomfort with the surveillance, forced vulnerability, and moral gray zones makes him a canary in the coal mine.

Comey is a signal that Bridgewater’s culture is inhospitable to independent thought or external accountability. His arc demonstrates the firm’s inability to assimilate those unwilling to surrender personal ethics to organizational orthodoxy.

Themes

Power and Control

One of the dominant themes in The Fund is the persistent struggle over power and the methods of control employed at Bridgewater Associates. From the very beginning, Ray Dalio structures the firm not simply as a financial institution but as an ideological system built to replicate and sustain his worldview.

What emerges is a culture where mechanisms like radical transparency and believability-weighted decision-making serve not only as tools for efficiency but also as instruments of power consolidation. These systems—Dot Collectors, psychological evaluations, and constant surveillance—give the illusion of meritocracy but often reinforce the existing hierarchies and Dalio’s authority.

The theme intensifies across the book, as even Dalio’s chosen successors are pitted against each other, and loyalty tests become increasingly severe. By Part IV, this control tightens into a symbolic “Circle of Trust,” exposing how idealism morphs into authoritarianism.

Despite public proclamations of democratizing leadership, the structure continuously reorients to ensure Dalio remains at the center. Control is further cemented through his creation of “The Partnership,” a post-retirement apparatus that allows Dalio to retain influence from behind the scenes.

In effect, the book paints a picture of an organization obsessed with minimizing human error while ultimately falling prey to a single man’s psychological need for dominance.

The Corruption of Idealism

The Fund is also an inquiry into how noble ideals can become corrupt when institutionalized without accountability. Ray Dalio begins with the idealistic ambition of creating a company governed by truth, logic, and openness.

He introduces “The Principles” as a philosophical operating manual to eliminate bias and elevate collective decision-making. However, the implementation of these principles reveals a growing chasm between rhetoric and reality.

Employees are encouraged to be radically honest, but the honesty is often one-directional—aimed at subordinates and rarely welcomed when aimed upward. Dalio’s obsession with applying his ideology to every facet of the organization breeds an atmosphere where compliance masquerades as enlightenment.

What begins as an attempt at self-improvement becomes a system of compliance, where disagreement is labeled ignorance or heresy. Idealism becomes not a path to excellence but a justification for increasingly invasive and punitive measures, culminating in surveillance, public shaming, and psychological grading.

The idea of “radical truth” is thus weaponized, and instead of fostering intellectual growth, it curtails freedom. Copeland makes it clear that over time, Dalio’s principles become tools to rationalize contradictions, protect the hierarchy, and silence dissent, eroding whatever sincerity or reformist spirit the firm may have once claimed.

The Cult of Personality

Another critical theme is the cult of personality that develops around Ray Dalio. What begins as admiration for a successful founder evolves into an almost theological reverence.

Employees are trained not only to follow the company’s rules but to internalize Dalio’s philosophies as a way of life. His principles are treated as scripture; his feedback methods as sacred rituals.

Those who fail to embody the “Ray way” are not just seen as underperformers—they are viewed as incompatible with the firm’s moral and operational universe. This cultish atmosphere is especially apparent in the way the company reacts to external scrutiny and internal dissent.

Figures like James Comey—professionally accomplished, morally grounded, and ideologically independent—find themselves alienated within a system that cannot accommodate anything less than total assimilation. By Part III, Dalio’s ambition to encode his philosophy into artificial intelligence reveals his desire not just to guide the company, but to immortalize himself through it.

Employees are no longer just workers; they are disciples expected to submit to a higher organizational faith. The theme culminates in the declaration that “this is a religion,” confirming that Bridgewater has shifted from being a company with a strong culture to a belief system with a founder-prophet at its core.

The system is no longer about results but about veneration, with Dalio’s word as its most sacred authority.

Transparency and Its Contradictions

Transparency is one of Bridgewater’s most touted values, and yet it emerges in The Fund as one of the most paradoxical elements of the firm’s identity. Ray Dalio’s concept of radical transparency is meant to eliminate politics, improve accountability, and foster learning through open dialogue.

Meetings are recorded, feedback is public, and decision-making is theoretically distributed based on credibility rather than rank. However, Copeland shows that this transparency quickly morphs into surveillance.

Employees feel constantly watched, graded, and interrogated. Instead of freedom and safety, they experience anxiety and conformity.

More disturbingly, the transparency is not symmetrical. Those in power remain shielded in many ways, able to demand openness from others while protecting their own authority through selective disclosure and manipulation of narratives.

The handling of scandals—especially those involving misconduct—further undermines the transparency ethos. Investigations are biased, victims are silenced, and accountability is sparse.

The notion of transparency becomes a mask, one that conceals power plays, protects insiders, and punishes outsiders. By the final chapters, even Bridgewater’s internal critics concede that what passes as radical openness is often just a sophisticated form of control and coercion.

Dehumanization in the Pursuit of Perfection

Throughout The Fund, Copeland illustrates how Bridgewater’s systems, initially designed for excellence, end up dehumanizing the very people they claim to empower. Employees are treated less as individuals with context and more as components of an abstract machine.

Every mistake is subjected to “root cause” analysis, every interaction fed into performance matrices, and every thought judged for logical soundness. The emphasis on continuous feedback, algorithmic evaluation, and emotional detachment creates a work environment that rewards robotic conformity over human insight.

People begin to self-censor, not just to avoid embarrassment but to survive emotionally. This system becomes particularly brutal for those who don’t fit the mold—those with dissenting views, vulnerable backgrounds, or simply more emotional or empathetic personalities.

The book recounts several stories where emotional breakdowns, mental health issues, and public humiliations are dismissed as necessary sacrifices for the higher goal of optimization. By embracing this kind of mechanized perfectionism, Bridgewater loses sight of basic empathy, trust, and community—the very traits that any sustainable organization needs.

In its quest to build the perfect decision-making organism, it ends up treating its people like flawed inputs rather than valuable ends in themselves.